Spirituality is a resource for African American gay men living with AIDS. Spirituality has been used to confront life-threatening events (Matheny & McCarthy, 2000) and physical illness (Heinrich, 2003) as well as emotional and psychological stresses (Culliford, 2002; Koenig & Cohen, 2002; Morita, Tsunoda, Inoue, & Chihara, 2000). Belief in God is an important contemporary and cultural strength for many African Americans (Mattis et al., 2004; NelsonBecker, 2003) and is a frequently cited element of Christian spirituality. As children, through spiritual formation and religious education many African Americans have been taught to foster a relationship with God (Mosley & Burgan-Evans, 2000; Jackson, Chatters, & Taylor, 1993). Within the family, spirituality is developed through formal and informal practices. Spirituality is influenced by participation in religious practice and belief (Helminiak. 2001). Religious practice is often conceptualized as a sociological phenomenon embodying codes of conduct, which are understood by interpretation of religious texts. The interpretation of such texts is the subject of sermons that are preached during worship services.

In a study examining how 10 African American gay men living with AIDS understood and used spirituality, Miller (2000) found that each received formal and informal instruction in spirituality as children. As adults, these African American gay men straggled to use its benefits. Miller (2000) and Woodyward, Peterson, and Stokes (2000) have documented that sexual orientation and behaviors of African American gay men are often judged as inconsistent or in conflict with religious codes of conduct and are held to constitute a transgression or sin (Gross & Woods, 1999). Many men internalize these judgments. They also experience retribution from those who are authority figures in places of worship. The retribution for such transgressions includes possible exclusion from places of worship. It may also result in negative self-perceptions or an inability to formulate a spirituality that is useful in confronting other life stressors. Such outcomes are problematic for some African American gay men when coping with AIDS.

Fullilove (1999) has used "place stories" to explore how people manage forced relocation from places that are significant to them. She defines place stories as "a narrative of the unfolding of a situation, understood as a complex interpersonal episode, in which place is an important part of the story" (p. 3).

The place story analyzed here highlights the desperate struggle of an African American gay man to use spirituality to confront AIDS. After hearing from his physician that he would die within 3 months, he accessed social supports and prayer to experience a tangible, healing presence of God. Many African Americans have described being "touched by God" or receiving the Holy Spirit, which is conceptualized as a manifestation of God, in a church during a worship service. There are fewer accounts of "being touched by God" in a hospital room. There are still fewer accounts of African American gay men living with advanced AIDS facilitating such an event. This article recounts how an African American gay man with AIDS transformed a hospital room to a prepared place to be touched by God. This story is examined because it presents an example counter to the acceptance of exclusion that often characterizes the life stories of African American gay men.

BACKGROUND

African American Worship

African American worship typically occurs in the context of Black churches, which may be understood as both places of worship and as multidimensional institutions. Though there is a wide variety of churches organized by African Americans, they are often referred to as "the Black church." Lincoln and Mamiya (1990) describe the church as having "its historical role as lyceum, conservatory, forum, social service center, political academy and financial institution, has been and is for Black America the mother of our culture, the champion of our freedom, the hallmark of our civilization" (p. 3). The reference to the Black church as an "institution" not only allows some readers to make a connection with their personal experience of the entity but also creates for other readers a mythic, monolithic assumption about these African American religious institutions that may not be accurate (Blackwell, 1985). Understanding that the Black church is not a monolithic entity is salient because the experience of African American gay men may vary across religious denominations. The similarities are emphasized in the following description of these institutions.

Worship in Black churches provides an opportunity for African Americans and others to engage in social networks, a collective catharsis and spiritual formation. The congregation is comprised of people who, through joining with the church, become members of the church community. The church members experience both tangible and intangible benefits. Belonging to a church community helps satisfy an essential need for belonging, a feature present in all cultures (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). For many African Americans, worshiping as a member of the church community provides a historical and cultural connection to the past that was disrupted by the enslavement experience (Rychlak, 1988) refuge (D'Apolito, 2000: Masten, Best, & Garmesy, 1990): and a weekly opportunity for a collective catharsis and gathering of support and strength (Lincoln & Mamiya, 1990). When various events such as births or weddings occur in the lives of the individual members, the community gathers to share in the celebration. During times of sickness or death, the community gathers to provide emotional and material support. In this way the church is, among other things, a sanctuary for healing.

The spiritual formation that occurs through African American worship is established, in part, through the sermon. Sermons are religious statements that use the Bible as their source. These statements typically contain expectations of establishing and sustaining a relationship with God that will provide hope, healing and strength (Taylor, 1972). For most African Americans, Christian spiritual formation and religious training includes believing in the Trinity: God as the creator of the universe, Jesus as his son who provides salvation for the soul of the individual, and the Holy Spirit who acts as a comforter and guide (Helm, 2001; Jones, 1986; Wells, 2002). A relationship with the Trinity is characteristic of Christian believers.

The interaction between the individual and God is a crucial theme (Maton, 1989; Pargament et al., 1988: Pollner, 1989: and Potts, 1996). God can be viewed as a material resource and a member of a social network, who like other network members can offer help (Coyne & DeLongis, 1986). As a member of the network, God serves as an emotional, instrumental, and informational support (Tardy, 1985). Cone (1975) suggests this interaction is seen as "a personal relationship with God that can be counted on in 'the times of trouble'" (p. 23).

The Clergy in African American Worship

Within African American worship, the clergy occupy the most authoritative and prestigious position in the church (Stark & Bainbridge, 1987). They are expected to nurture the spiritual life of church members through preaching, pastoral care, instruction, and example (Proctor, 1994). The clergy also provide the voice of authority regarding codes of behavior. The sermon has been used by the clergy to admonish the congregants to refrain from behaviors that the clergy perceive to violate scripture. Those clergy who interpret homosexuality as a violation and sin use their sermons to admonish homosexual men and women.

Gay Identity

The sexual identity of African American gay men is usually not positively regarded by heterosexuals or other homosexuals. As in mainstream American culture, African Americans prefer heterosexuality and consider it normative (Lewis, 2003). This heterosexism is deepened by a lack of acceptance by friends and family. Stokes, Vanable, and McKirnan (1996) reported that African American gay and bisexual men were less likely than White gay and bisexual men to perceive their friends and neighbors as accepting of same-sex behavior among men. Some African American gay men are taught that their sexual orientation and behavior is at at odds with being African American and is inconsistent with their religious training (Staples, 1982: Welsing, 1990). Boykin (1996) suggests that homosexuality is not preferred by African Americans and that African American gay men must negotiate their sexual orientation with social acceptability. Such men confront many stressors, which have been linked to the maintenance of closeted homosexuality, referred to in the common parlance as "down low." It is important to note that few empirically based statements can be offered about closeted African American men because of the absence of research among such men (Malebranche, 2003).

Identity development for African American gay men is important to their self-esteem. Crawford, Allison, Zamboni, & Soto (2002) found that African American gay and bisexual men who possessed more positive (i.e., integrated) self-identification as being African American and gay reported higher levels of self-esteem, HIV prevention self-efficacy, stronger social support networks, greater levels of life satisfaction, and lower levels of male gender role and psychological distress than their counterparts who reported less positive (i.e., less well integrated) African American and gay identity development. Crawford et al.'s findings suggest that men who are both African American and gay or bisexual are capable of integrating their respective identities and engaging in positive experiences in their lives despite the various challenges they confront.

Yet, because of the importance of the church for African Americans, the dominant view that homosexuality is a violation or sin constitutes an important assault on the self and prompts a variety of coping responses for gay men. To assuage the negative feelings that can arise in the face of religious castigation, some men feel they have to make a choice: They must either forego their sexual orientation and behavior to remain consistent with the scriptural interpretation of their clergy or they must reject the clergy's interpretation and potentially lose access to their church affiliation (Miller, 2000). The consequences of such choices are severe, potentially leading to diminished self-esteem and limited ability or willingness to pursue further spiritual development (Hicks, 2000). For some men, religious castigation and the forced choice it imposes encourage unsafe sexual practices and drug use (Fullilove & Fullilove, 1999). However, other men who have a strong gay identity and highly developed sense of human agency are able to temper the impact of the negative feelings.

Human Agency

Human agency accounts for the ability of African American gay men and others to confront challenges and achieve their desired outcomes. Agency--the capacity or ability to exert power--has been identified by Albert Bandura and others as a means to negotiate one's environment, including difficult circumstances (Thoits, 2003). People's belief that they can produce desired effects and forestall undesired ones by their actions is central to their willingness to act (Bandura, 2000a, 2000b). Mobilizing such internal resources in favor of their self-preservation helps to shape responses to difficult life challenges.

AIDS

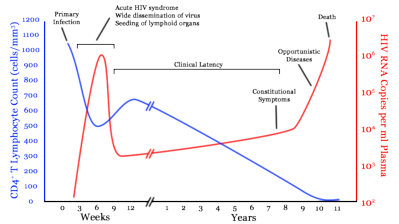

For African American gay men who must contend with threats to their religious, group, and cultural affiliations as well as their sexual identity, the onset of AIDS is one more threat to their existence. AIDS creates a profound trauma in most people's lives. The spectrum of the disease course, including the tear of what might happen, living through the deterioration of health during an unspecified time, and finally experiencing acute AIDS symptoms, are all difficult.

Pharmacological advances have not eradicated HIV disease. However, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has been shown to be effective in suppressing viral replication and restoring immune functions (Dyer et al., 2002). While there is cause for optimism as the HAART treatment options have dramatically shifted the experience of AIDS for many people, data efficacy of HAART is unavailable at the time of this writing (2004).

People living with an AIDS diagnosis continue to experience a unique stigma compared to other diseases (Poindexter & Linsk, 1999) and are perceived as responsible for and deserving of their disease (Johnson, 1995). Furthermore, there are social and religious institutions that as a matter of doctrine and practice repudiate same-sex behavior (Greaves, 1987; Staples, 1982). Living with AIDS and experiencing blame for contracting the disease is a profound assault on one's emotional and psychological health. These stressors create additional difficulties.

Internalized Dislocation and Threats' to Agency

The repeated stigma experienced by African American gay men living with AIDS can lead to an internalization of negative messages and even a tendency to accept and act on these judgments. At the same time, these men may experience weakened connections with important people and institutions in their lives. As suggested above, the church is one such institution. For those who grew tip in church, the sermons castigating homosexuality can be an alienating experience. These feelings potentially challenge their willingness to continue church attendance, and for some men, they may threaten how they experience a relationship with God. Furthermore, feeling unwelcome in a place that has held historical emotional connections while experiencing questions regarding the viability of a relationship with God may challenge how people relate to themselves and their environment, undermining their personal agency. These threats to their personal anchors, their understanding of their place in the world, and their feelings about themselves create a sense of dislocation.

One African American gay man living with AIDS told a story of managing his dislocation from the church of his youth. Learning that his physician had given up on him and predicted his imminent death, the informant decided to mobilize his resources to save himself. He accomplished this task by relocating the church to his hospital room. It is the dislocation-relocation process embedded in this narrative that is the subject of this paper.

METHOD

The data analyzed for this study was a portion of a single transcript from a larger study titled "The meaning and utility of spirituality in the lives of African American gay men living with AIDS" (Miller, 2000). The informants, African American gay men living with AIDS, were recruited using advertisements in various AIDS service and religious organizations in Manhattan and Brooklyn, New York. Specifically targeted agencies included Gay Men's Health Crisis, Unity Fellowship, Brooklyn AIDS Task Force, and Gay Men of African Descent. Flyers were also distributed in gay clubs and civic organizations. Informants were also asked to identify people they thought would want to participate and ask them to contact me. In addition, personnel from these agencies assisted in recruitment by informing potential participants outside their agencies about the study. When the respondents called, I screened them for eligibility based on whether they were between 35 and 50 years old; had an AIDS diagnosis which was verbally confirmed as the project was explained to them; were psychologically capable of engaging in conversation; claimed United States citizenship; had African ancestry; spoke English; identified as gay; and were raised in an African American family where spirituality was taught as an important ideal. Seventeen men contacted me expressing an interest in the study. An additional screening was conducted to determine the willingness and ability of each informant to participate in three interviews lasting between 90 and 110 minutes. I told each participant that the information he shared would be held in confidence, gave each participant a consent form, and told each participant he could discontinue his participation at any time.

Participant

Though each of the informants from the larger study related an encounter with God, the selected narrative provided by Larry offers an exemplar of a place story, in which Larry used spirituality to manage his crisis. The narrative illuminates his agency and describes the circumstances, the event, and the aftermath of a meeting with God as understood by the informant.

Data

The narrative begins after Larry had been stabilized after an emergency room visit. It was late October and he had been complaining of shortness of breath, difficulty in ambulation, and generally feeling very sick. His doctor told him that he had end-stage AIDS and there was nothing more he could do for him, and that he should expect progressive, degenerative paralysis and that he would "be dead by Christmas." Larry immediately rejected the physician's prognosis and invited the entire medical team to leave his hospital room. He then formulated a plan. First, he called friends who were experienced in prayer and asked them to come to the hospital to pray with him. They agreed, and after the bedside prayer, they organized a prayer vigil for him among his extended friends and family. Larry prepared the nursing staff and the hospital room in anticipation of the appointment by telling them not to disturb him through the night. He then made an appointment with God at a specified time. At the appointed time, he began to pray to God. Alter time passed, he realized that God was not answering him in a timely way and he became frustrated. His frustration and anxiety escalated. Larry then experienced the divine response. Later in the morning, he recounted to his friends the sequence of events and the successful outcome.

Analysis

I analyzed the narrative phrase by phrase. Afterwards, I organized the text into sections, which allowed for an understanding of the individual actors, the setting, the sequence of events, and the complex interpersonal episode (Fullilove, 1999). Through these assembled sections, I organized and presented their intention and meanings as a series of events with interpretation. After the structure of the story was organized and I completed an interpretation, I had a subsequent conversation with the informant to determine if the interpretation was consistent with his intended meaning (Creswell, 1998). Through this iterative process, an accurate representation of the material was constructed. The portion of the narrative I analyzed is presented in the Results section.

RESULTS

Part I: Larry's Background

At the time of the interview in 1999, Larry was 51 years old. He had been diagnosed with AIDS in 1990. He had two older sisters and a younger brother. As children, they lived with their parents and maternal grandmother. Religion was important to his family, and he was reared as a Roman Catholic. Although practicing Roman Catholics, his parents divorced because of his father's alcoholism. As a result of the custody hearing, Larry and his brother lived with their father while his sisters lived with his mother. Larry experienced many episodes of physical abuse from his father. When Larry was 12, after a "terrible fight" with his father, he and his brother went to live with his mother. Prior to his father's death, Larry was able to reconcile his relationship with his father.

His mother and grandmother were the primary emotional supports among a loving family. They also taught him that an intimate personal relationship with God was a high priority. This relationship was fostered by parental training, including mandatory church attendance until he was 16. After 16, he continued regularly attending church because he liked it. His church community became an extended family for him.

It was in church that he experienced extraordinary spiritual occurrences. When he related those events to his priest, the priest affirmed them as messages from God. His priest also encouraged him to deepen his relationship with God. In other parts of the narrative, Larry said that his priest predicted that he would become a priest.

While his mother expected the church to be instructive in his religious and spiritual development, she monitored the messages he received. Messages that were inconsistent with her beliefs were filtered. His mother did not see the church as the ultimate arbiter between God and humanity. She believed that an individual could have direct access to God. The individual would pray to God and God would respond to the individual. Her overt message was that "individuals can initiate and experience relationships with God." The meta-message was that individuals can make things happen for themselves with God's help. Larry told the following story, which illuminates how she molded his religious experience:

As an adult Larry organized his life to embody the his tory of his familial traditions of personal spirituality as well as religious beliefs and practices that were consistent with his life experiences and his understanding of the relationship he shared with God. Prior to his ordination to the ministry of the Unity Fellowship, he was nationally ranked in the martial arts, a manager of an internationally known African American gay dance club, and later an AIDS activist. In 2001, he was awarded an honorary doctorate from a theological college in England. In 2002, Larry became the pastor of a small, vibrant sect of Christian gay men and women. He preached a theology that affirmed the human dignity and worth of person regardless of their sexual orientation, gender, socioeconomic status, physical capability, or disease status.

As an African American gay man with AIDS, Larry possessed many characteristics similar to other such men. He was born to a Christian family that instilled the values of love, respect, honor, and care. Larry was also involved in activities that developed and instilled discipline, self-esteem, and self-care.

He was, however, unique in the solidity of his self-concept. By the time he heard denigrating messages that repudiated his sexual orientation, all of his previous training had seemingly inoculated him. When he came of age to understand that the church that first nurtured him characterized him in its dogma as an abomination and rejected his same-sex desires and behaviors as "acts of grave depravity" (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1994) and "intrinsically disordered" (Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, 1975, p. 8), he realized he was being rejected from the church. Because of his sexual orientation and expression, he was no longer welcomed in the institutional Roman Catholic Church. To be welcomed, he would have to agree to celibacy for the rest of his life. This rejection created a dislocation from the church of his childhood. However, he experienced this dislocation as a rejection from the church but not as a rejection or dislocation from God. His previous teachings sustained and encouraged him to become more committed in his relationship with God. In effect, he believed the truth of his experience, namely that he was loved by God and that God had heard and would hear his prayers. The church was the place of his earliest religious education and spiritual formation (outside of his family) but became a place of negative messages. Larry then relied on his personal relationship with God. By doing so, he was able to create sacred places where and when he needed. His potential dislocation was reframed to permit relocation.

Part II: Context

In his hour of need, Larry believed that he might call God to come to him. In the appendix, the complete story of Larry's appointment with God is presented. In the following sections the key events are discussed.

The call: Lines 1 through 6. The story begins with Larry's rejection of the physician's prediction of death and his preparing to fight for his life. To engage in that fight, he called together his "army," which was a network of people. These included a smaller group of people with a specific task and a larger group charged with variety tasks. The smaller group, the "prayer warriors," were people with a talent for prayer, a firm belief in his full recovery, and a strong, personal relationship with God.

The network response: Lines 10 through 21. Larry described three activities undertaken by the network: deep prayer, a prayer vigil, and treatments by complimentary healers. Deep prayer is a specific, intentional prayer requiring the full concentration of the prayer warriors. In Christian scripture, such prayer is distinguished from "shallow" work (Psalms 18:16; Psalms 107:24; Luke 5:4). The concept of deep is used to describe the magnitude of the circumstance of someone who is lost and needs to be found or saved. The deep work is not done alone but rather in collaboration with others who have agreed on the intention and are committed to the same outcome. Deep prayer was required because the warriors were interceding on behalf of their friend against a foe that could take his life.

The preliminary work for the appointment: Litres 25 through 44. Prior to calling on God, Larry believed that he must establish the intention, prepare the space, and set aside an uninterrupted time. This was the second of three efforts to change the hospital space to be conducive for Larry's healing. The first effort was calling together the prayer warriors, and the third effort was Larry's personal effort of seeking God during his time of need.

Larry determined that his appointment with God was going to be "this night," which is a significant decision. Though rarely acknowledged, there is an implicit hopefulness in nighttime. It is both progressive and limited. Nighttime has a beginning, a middle, and an end. One goes through the night in the hope of seeing the dawn of a new day. There is a desire in this hope that there will be some positive change, another chance for the condition to improve. The anticipation of a new day, while trying to get through the night, sustains the desire.

Some suggest that the night is darkest between midnight and dawn. Larry made an appointment with God at the time when the transition from night to a new day begins: at midnight. In his appointment, he petitioned and expected God to create a change in him with the arrival of the new day.

Larry's midnight appointment has an historical context in relationship to African American religious history and social history. The New International Version of the Bible includes 13 events that happen at midnight. Many of these events are about freedom or a reprieve from danger. For example, religious prisoners Paul and Silas were freed at midnight while they were praying and singing (Acts 16:25). Paul was visited by an angel who told him that while his ship would be wrecked, all of the crew would be saved if they stayed in the vessel (Acts 27:27-44). African American slaves held their worship services at night to avoid being seen by the slaveowners and subsequently punished. Slaves tried to escape to freedom during the night. Much of the effort of the Underground Railroad happened at night.

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and others have offered commentary on the metaphor of night as a time of confusion and uncertainty. In an effort to provide encouragement and direction to the Black church during the Civil Rights movement, Dr. King (1963/1986) wrote the following:

It is against this backdrop that Larry told God to come to him at midnight. He used the nighttime, specifically midnight, because in other instances God has acted at midnight. Larry planned to seek, cajole, challenge, and demand that God show up and do for him what God has done so many times for others.

The prayer of appointment: Lines 48 through 51. As Larry began to pray for God to visit, he was making a declaration of faith, which proceeded from his early religious education and spiritual formation. His religious education and spiritual formation was centered in knowing that God would respond to petitions that were asked with confidence. This moment also signaled an ultimate test of faith. When confronted with death, he believed one must answer the questions "What do you believe?" and "What are you going to do about it?" The crux of Larry's story is not unlike the Biblical stories in which men and women were faced with their end and they decided to call on the name of the Lord. In a time of profound crisis, seeking God is an effort to create a positive change in the situation. This is one example of Larry's previous religious training supporting his current crisis.

The call to God: Lines 55 through 58. Larry began to call on God using what he called the "pretty prayer.'" The pretty prayer can be contrasted with the deep prayer of his warriors. The pretty prayer is that which includes little in the way of petition and may not reflect the gravity of the need or situation. It is the pretty prayer because it offers all the appropriate preliminary statements about the sovereignty of God.

The prayer was formulaic. First, praise and adulation were offered, followed by the petition. Larry described the crisis and the reason for the appointment. He told God about his pain, paralysis, and predicted death. The shallow, pretty prayer was interrupted by severe pain, which brought home the seriousness of the situation. Two movements occurred at that point: Larry moved from humble admiration of God to claiming the rights of relationship, and at the same time the hospital became a sanctuary for healing.

Taking too long: Lines 62 through 99. Despite Larry's need, God did not arrive immediately. At that point, the quality of the prayer shifted dramatically. Larry began to confront God and demand His accountability. In that moment, he insisted that God show up and engage him in the conversation. Filled with exasperation, frustration, and fear, Larry yelled at God, "You are a chicken!" In the midst of his pain, he was still conscious that he was yelling at the "Creator of the Universe." In desperation and fright, Larry was doing all that he could to make God appear. This speaks to the intimate relationship he felt he shared with God. as well as the bargain that he had made by being a good Christian. He pointed out to God that he had kept his part of the bargain: "I have fed people. Clothed people, sheltered people, prayed for people." And he pleaded, "I did my part, now you do yours. Be with me--make yourself known to me!"

During one of his moments of high anxiety, Larry remembered, "I am like in God's face at this point." The passage indicates he had personalized and humanized God. Larry could not walk, yet he was "in God's face, screaming and hollering." He was in the face of God, the very same God who had not appeared. It is not an overstatement to say that Larry had reached the end of his rope. He was rageful, very frightened, and could not figure out what else to do to make God show up.

In this same section, Larry noted, "This was about 2:30 in the morning and the nurse comes running in the room." The arrival of the nurse is important. First, it signaled that Larry had been seeking God for nearly three hours. Second, the room was a still a hospital room for the nurse, however much Larry was transforming it for a place for God to appear. Larry and the nurse had different understandings of the same space.

God's response to Larry: Lines 103 through 117. Suddenly, Larry felt a pressure on his chest, "and something pressed me down." In that moment, God was present and Larry knew it. This event--the touch, the assurance, the appearance and leave-taking of God--did not take a long time. Yet, at that moment Larry felt that he had achieved a moment of clarity and attained the hope he was seeking.

The testimony: Lines 121 through 137. When the medical team entered Larry's room for morning rounds, he was in a happy mood. When questioned by the medical team, Larry was careful to say that "the medicine must be working." There was some sort of cynicism in his response. That he did not explain to the medical personnel what happened to him in the predawn hours is an indication of his perception of their role in his care. They provided the technical medical functions, but he had additional needs for which they could not provide. They are part of the space as hospital room, but not the sanctuary that was visited by God.

His prayer warriors, by contrast, learned the story of the midnight appointment. In fact, as Larry related, "They simply looked at me and said, 'Something happened.' I said, 'God talked to me, I will be OK. Pay the rest of this no mind.'" The "rest of this" was the work that Larry would do for himself. However hard that work might be, it would be possible because God had come to the hospital room.

DISCUSSION

This study reveals how an African American gay man with AIDS used spiritual resources despite dominant messages in society suggesting his unworthiness of those resources. By drawing on his spiritual and cultural strengths, he was able to envision an earthly future for himself. Whether or not one believes that God intervened and saved his life, Larry asserted his fight to be helped by the God of his forefathers. A number of strengths helped him to resist internalized dislocation and to relocate God and the benefits of African American worship and church. The following discussion summarizes and synthesizes the main findings of this study.

Larry did not want to die, and therefore he initiated a process to save himself. He used early Biblical training, religious education, and spiritual formation in designing his intervention. Though he realized that the Bible has been used by some people to validate killing human beings, to enforce slavery, to reject homosexuality, and to subjugate women, that was not how he used the Bible. He believed the Bible to be a tool for empowerment and strength. In so doing, he acted in a manner that is common among many Black people. Using the texts of the Bible that are compatible with one's struggle for life and freedom is a consistent theme among theologians who examine the utility of scripture in the lives of Black people (Douglas, 1999; Wimbush, 1998). As Wimbush (1998) suggests,

Wimbush (1998) uses Stendal (1966) to further the point:

The data also reveal Larry's willingness to relocate the place where God can be experienced. There is a cultural and religious precedent for this behavior. African Americans have experienced stigmatization in religious institutions and have had the courage to leave those churches to create new places to worship. Richard Allen in 1787 led a group of African Americans from an Episcopal worship service where their participation was restricted to sitting in pews in the back of the balcony. He then started the African Methodist Episcopal church. This relocation attended to their need for dignity, equality, self-expression, and fuller involvement in the service of the worship of God and in society as a whole.

Agency and Spirituality

Larry's beliefs and coping response to AIDS are consistent with Albert Bandura's work in social cognitive theory describing human agency. Bandura suggests that people engage in behaviors they believe will produce certain outcomes. Larry believed he could initiate and experience an encounter with God that would save his life. Acting on that belief, he also employed what Bandura (2002) termed proxy agency and collective agency. Proxy agency occurs when people secure desired outcomes by influencing others to act on their behalf. Calling on God is one such activity. Collective agency occurs when people act in concert to shape their future. The call to the prayer warriors and the nonlocal prayer vigil are examples of such action.

Through mobilizing himself to employ his spiritual beliefs and training, Larry demonstrated an integration of spirituality and agency, which I will call "spiritual agency." His relationship with God, supported by his formal and informal religious training, allowed him to believe that he could engage in behaviors that would yield desired outcomes. This spiritual agency provided the motivation and the capacity to call on God in a time of trouble.

Place and AIDS

Larry's hospital room became a sanctuary or holy place because Larry invited God's presence and intervention. For Larry, God was not bound by a specific place. Churches and other sacred places become so by the invocation of human beings. People solicit the blessing and presence of God on a space, any space, and it is believed that God responds by blessing and being present in the space according to the need of the petitioner.

Though Larry was a Christian and believed in God, this story is not related as a religious testimony. Rather, it provides a detailed examination of the way in which several elements--African American struggles for freedom, a mother's insistence on human dignity, and a son's ability to hold onto his personal worth--laid a foundation for a creative act that gave hope in a moment of despair. It is remarkable how much collective resistance created the strands that Larry wove together to create his appointment with God.

APPENDIX

TRANSCIPT OF "APPOINTMENT WITH GOD"

1

2 I called some friends, I said, I need people to come pray with me, who know I will get up.

3 I don't need nobody, believing, l don't need no body in a pity mood.

4 I don't need none of that.

5 I need warriors.

6 I need people who know God now!

7

8

9

10 I had eight people to come up to my room.

11 They circled my bed. We went into prayer.

12 And it was funny.

13 I had a nurse opened the door, she looks around and says, "Is everything ok?"

14 Nobody moved. We are in deep prayer.

15 We go into meditation for about 20-30 minutes and everybody is smiling.

16 Nobody said anything but smiling.

17 I said, "Ok. Go to work."

18 They started a prayer vigil for me.

19 Um, I had a herbalist that was coming.

20 I had an acupuncturist coming into the room, working with me behind the closed door.

21 They sent me a therapist.

22

23

24

25 Oh, that was the night I had this conversation with God.

26 I felt like I have told you this.

27 That night, at 11:45 I called the nurse and said, "Bring all the medication you need to give to me.

28 After 12:00 I don't want you to open the door."

29 Now understand, I was taking like two percasets and a sleeping pill to try to get maybe four or

30 five hours of sleep.

31 I was in major pain.

32 Everything hurt.

33 You could not touch [me] my body had swollen, the joints, I was sucking out of a straw.

34 If you touched me like this, it was pain.

35 The acupuncture did not hurt, no.

36 You don't feel those needles.

37 So, here I am.

38 I tried not to take pain medicine but when pain is constant, 24/7 you can only mentally control

39 so much.

40 So, I swallowed the percasets to ease the pain and to keep going.

41 This night, I say bring everything you got.

42 She brings the drugs and asks, "what else?"

43 I said, I am going to have a conversation with God tonight.

44 I don't want you to open the door until the sun comes up.

45

46

47

48 At 11:45, my prayer was to God, "Listen, at 12:00 I need your full attention.

49 So do what you got to do, but at 12:00 I need your full attention.

50 Ok?

51 Let somebody else run the universe for a minute."

52

53

54

55 At 12:00 I started praying.

56 It was the pretty prayer.

57 In the beginning, you know the sweet prayer, "Oh heavenly father ... you are the Creator.

58 I, your child, humbly bowing before you," you know that sweet prayer?

59

60

61

62 But, baby after a while, that pain said, what's my name?

63 What's my name, what's my name!?!?!?

64 And you are trying to pray, "oh, God, you know I know you can ..." [grunt for the intensity of

65 the pain] heal me, and at that point, I just started hollering at God.

66 I called God everything.

67 I told God, "You are chicken.

68 You won't show up.

69 Talk to me.

70 You are going to talk to me!

71 I have done everything you have ever asked me to do.

72 I have fed people.

73 Clothed people, sheltered people, prayed for people.

74 I have done everything you have ever asked me to do.

75 You will not leave me.

76 You are going to show up and talk to me tonight!"

77 Now mind you, I am screaming at the top of my voice now.

78 I could not stand up.

79 My feet were swollen.

80 I am sucking out of a straw.

81 To pick up something, I had to use two hands.

82 Um, I got IVs going everywhere.

83 And, the wind is blowing.

84 And I am saying, "No!

85 I don't need you to blow the wind.

86 I know you can make the wind blow and I can't interpret anything right now.

87 Talk to me."

88 I am screaming at God.

89 I am at the point where I am calling God chicken, "You are chicken.

90 You won't show up.

91 You are scared to face me.

92 If you are so great, you face me!"

93 This was about 2:30 in the morning.

94 The nurse comes running in the room, and hollering, "Can I help you?"

95 I said, "Is your name God?"

96 She said "No."

97 I said, "Get the hell out."

98 I am like in God's face at this point.

99 I am screaming and hollering.

100

101

102

103 And something pressed me down, just like this (he takes his finger and presses his chest). And it

104 said, "You will be ok!

105 I am here."

106 Now mind you, this happened at a point, when I am saying to God, "Take my breath!

107 Take my breath.

108 You are not going to leave me like this.

109 Just take my breath!"

110 And that is when it went, "You will be ok, I am here."

111 I heard it as clearly as you can hear nay voice.

112 Now at that point, I got real quiet.

113 I did not know if it meant, "You will be ok, I am here because I am about to take your breath."

114 Or, "You will be ok, I am here and don't worry about anything."

115 So I needed a moment of clarity [laughter].

116 Oh, you know I did not mean it like that! [laughter].

117 You such a good God! [laughter].

118

119

120

121 Baby, they came in the morning, I am lying in the bed.

122 Listening to Sweet Honey, singing I feel better, so much better, since I laid my burdens down!

123 You want blood pressure here, "I feel better, so much better."

124 "Medication?" "Thank you!"

125 "So much better, since I laid my burden down."

126 Baby they looked at me like I had lost my mind.

127 Yes, I had not been to sleep all night.

128 I am up praising God.

129 They looked at me, "blood pressure normal, everything normal."

130 They are like, "the medication is working."

131 I'm like, um hmm.

132 My friends, when they were coming to the hospital, when I told them what happened, they

133 walked in and they said, the ones I told to circle me with prayer ...

134 They simply looked at me and said, "something happened."

135 And I said, "un huhn."

136 I said, "God talked to me, I will be ok.

137 Pay the rest of this no mind."

REFERENCES

Bandura, A. (2000a). Exercise of human agency through collective efficacy. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 9, 75-78.

Bandura, A. (2000b). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1-26.

Bandura, A. (2002). Social cognitive theory in cultural context. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 51, 269-290.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation, Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497-529.

Blackwell, J. E. (1985). The Black community: Unity and diversity (2nd ed.). New York: Harper and Row.

Boykin, K. (1996). One more river to cross: Black and gay in America. New York: Anchor Books.

Catechism of the Catholic Church. (1994). Chicago: Loyola University Press.

Cone, J. H. (1975). God of the oppressed. San Francisco: Harper.

Coyne, J. C., & DeLongis, A. (1986). Going beyond social support: The role of social relationships in adaptation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54, 454-460.

Crawford, I., Allison, K. W., Zamboni, B. D., & Soto, T. (2002). The influence of dual-identity development on the psychosocial functioning of African-American gay and bisexual men. The Journal of Sex Research, 39, 179-189.

Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Culliford, L. (2002). Spirituality and clinical care. British Medical Journal, 325, 1434-1435.

D'Apolito, R. (2000). The activist role of the Black church: A theoretical analysis and an empirical investigation of one contemporary activist Black church. Journal of Black Studies, 31, 96-123.

Douglas, K. B. (1999). Sexuality and the Black church: A womanist perspective. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books.

Dyer, W. B., Kuipers, H., Coolen, M. W., Geczy, A. F., Forrester, J., Workman, C., et al. (2002). Correlates of antiviral immune restoration in acute and chronic HIV type 1 infection: Sustained viral suppression and normalization of T cell subsets. AIDS Research on Human Retroviruses, 18, 999-1010.

Fullilove, M. T. (1999). The house of Joshua. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Fullilove, M. T., & Fullilove, R. E. (1999). Stigma as an obstacle to AIDS action: The case of the African American community. American Behavioral Scientist, 42, 1117-1127.

Greaves, W. I. (1987). The Black community. In H. Dalton & S. Burris (Eds.), AIDS and the law (pp. 281-289). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Gross, L., & Woods, J. D. (1999). The Columbia reader on lesbians and gay men in media, society, and politics. New York: Columbia University Press.

Heim, M. S. (2001). The depth of the riches: Trinity and religious ends. Modern Theology, 17, 21-35.

Heinrich, C. R. (2003). Enhancing the perceived health of HIV seropositive men: Response. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 25, 386-387.

Helminiak, D. A. (2001). Treating spiritual issues in secular psychotherapy. Counseling and Values, 45, 237-251.

Hicks, D. (2000). The importance of specialized treatment programs for lesbian and gay Patients. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Psychotheraphy, 3-4, 81-94.

Jackson, J. S., Chatters, L. M., & Taylor, R. J. (1993). Aging in Black America. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Johnson, S. D. (1995). Model of factors related to tendencies to discriminate against people with AIDS. Psychological Reports, 76, 563-572.

Jones, C. P. M. (1986). Liturgy and personal devotion. In C. Jones, G. Wainwright, & W. Arnold (Eds.), The study of spirituality (pp. 33-57). New York: Oxford University Press.

King, M. L. (1986). The strength to love. In J. Washington (Ed.), A testament of hope (pp. 491-518). San Francisco: HarperCollins. (Original work published in 1963)

Koenig, H. G., & Cohen, H. J. (2002). Psychological stress and autoimmune disease. In H. J. Cohen & H. G. Koenig (Eds.), The link between religion and health: Psychoneuroimmunology and the faith factor (pp. 174-196). London: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, G. (2003). Black-white differences in attitudes toward homosexuality and gay rights. Public Opinion Quarterly, 67, 59-78.

Lincoln, C. E., & Mamiya, L. W. (1990). The Black church in the African American experience. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Malebranche, D. (2003, November). Down low Black men and HIE: The truth behind the disparity. Paper presented at the University of Virginia. Charlottesville, VA.

Masten, A., Best, K., & Garmesy, N. (1990). Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology, 2, 425-444.

Matheny, K. B., & McCarthy, C. J. (2000). Write your own prescription for stress. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications.

Maton, K. I. (1989). Community settings as buffers of life stress? Highly supportive churches, mutual help groups, and senior centers. American Journal of Community Psychology, 17, 203-232.

Mattis, J. S., Fontenot, D. L., Hatcher, K., Carrie, A., Grayman, N. A., & Beale, R. L. (2004). Religiosity, optimism, and pessimism among African Americans. Journal of Black Psychology, 30, 187-207.

Miller, R. L., Jr., (2000). The meaning and utility of spirituality in the lives of African American gay men living with AIDS. Unpublished Dissertation, Columbia University, New York.

Morita, T., Tsunoda, J., Inoue, S., Chihara, S. (2000). An exploratory factor analysis of existential suffering in Japanese terminally ill cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 9, 164-168.

Mosley, H., & Burgan-Evans, C. (2000). Relationships and contemporary experiences of the African American family: An ethnographic case study. Journal of Black Studies, 30, 428-452.

Nelson-Becker, H. B. (2003). Practical philosophies: Interpretations of religion and spirituality by African American and European American elders. Journal of Religious Gerontology, 14, 85-99.

Pargament, K. I., Kennell, J., Hathaway, W., Grevengoed, N., Newman, J., & Jones, W. (1988). Religion and the problem-solving process: Three styles of coping. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 27, 90-104.

Poindexter, C. C., & Linsk, N. L. (1999). HIV-related stigma in a sample of HIV-affected older female African American caregivers. Social Work, 44, 46-61.

Pollner, M. (1989). Divine relations, social relations, and well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 30, 92-104.

Potts, R. G. (1996). Spirituality and the experience of cancer in an African-American community: Implications for psychosocial oncology. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology, 14, 1-19.

Proctor, S. (1994). The certain sound of the trumpet: Crafting a sermon of authority. Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press.

Rychlak, J. F. (1988). Unification in psychology: My way! Our way! No way! Contemporary Psychology, 34, 999-1001.

Sacred Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. (1975). Persona humana: Declaration on certain questions concerning sexual ethics. Rome, Italy: Author.

Staples, R. (1982). Black masculinity: The Black male's role in American society. San Francisco: Black Scholar Press.

Stark, R., & Bainbridge, W. S. (1987). A theory of religion. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Stendal, K. (1966). The Bible and the role of women (E. T. Sander, Trans.). Philadelphia: Fortress Press.

Stokes, J. P., Vanable, P. A., & McKirnan, D. J. (1996). Ethnic differences in sexual behavior, condom use and psychosocial variables among Black and White men who have sex with men. The Journal of Sex Research, 33, 373-381.

Tardy, C. H. (1985). Adjustment to threatening events: A theory of cognitive adaptation. American Psychologist, 38, 1161-1174.

Taylor, G. C. (1972). Introduction. In W. M. Philpot (Ed.), The best Black sermons (p. 6). Valley Forge, PA: Judson Press.

Taylor, R. J., Chatters, L. M., & Levin, J. (2004). Religion in the lives of African Americans: Social, psychological and health perspectives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Thoits, P. (2003). Personal agency in the accumulation of multiple roleidentities. In T. J. Owens, P. J. Burke, P. A. Thoits, & R. T. Serpe (Eds.), Advances in identity theory and research (pp. 179-194). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Wells, H. L. (2002). Beyond the usual alternatives in Buddhist-Christian dialogue: A trinitarian pluralist approach. Buddhist-Christian Studies, 22, 127-131.

Welsing, F. C. (1990). The Isis papers: The keys to the colors. Chicago: Third World Press.

Wimbush, V. (1998). Rescue the perishing: The importance of biblical scholarship in Black christianity. In J. H. Cone & G. S. Gilmore (Eds.), Black theology: A documentary history, Volume 2:1980-1992 (pp. 210-218). New York: Orbis Books.

Woodyward, J. L., Peterson, J. L., & Stokes, J. P. (2000). "Let us go into the house of the Lord": Participation in African American churches among young African American men who have sex with men. The Journal of Pastoral Care, 54, 451-460.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Society for the Scientific Study of Sexuality, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group