Rosacea is a skin disorder that occurs in adults between the ages of 30 and 60 years. Little is known about the etiology of rosacea. Current opinion regarding pathogenesis favors a multifactorial disorder in which the basic defect is vascular hyperre-sponsiveness. Symptoms include facial flushing, erythema, inflammatory lesions and, occasionally, lymphedema and hypertrophy of the connective and vascular tissue of the nose (rhinophyma). Therapy includes treatment with oral and topical antibiotics and surgery for erythema, telangiectasia and rhinophyma.

Etiology

The etiology of rosacea is believed to be related to a combination of a genetic predisposition and provocative environmental factors. Patients with rosacea tend to have fair hair and skin. They may have a tendency to flush frequently in response to emotional stimuli such as excitement, worry or a hurried feeling, environmental stimuli such as heat or cold, and physiologic stimuli such as indigestion, ingestion of spicy foods or postprandial fullness.(1)

The mite Demodex folliculorum inhabits facial hair follicles and has been implicated in the pathology of roseacea. The significance of the presence of D. folliculorum is uncertain, however, since the mite is variably present in patients with rosacea and is often found in control subjects.(2)(3)(4) Whether D. folliculorum is involved in the pathogenesis of rosacea is unknown, but it is possible that an inflammatory reaction to the mite may play a role in this condition.

The presence of bacteria within the hair follicle does not seem to play a role in the pathogenesis of rosacea, unlike the pathogenesis of acne vulgaris. Several investigators(5)(6) have failed to demonstrate bacteria in skin samples from patients with rosacea.

Many provocative factors have been shown to exacerbate rosacea by causing an increase in flushing. These factors include exposure to heat, cold or sunlight, and consumption of hot or spicy foods and alcoholic beverages.(7) It has been suggested that the basic problem in patients with rosacea is a functional vascular anomaly with a tendency toward recurrent dilation and flushing, which may result in inflammatory mediator release, extravasation of inflammatory cells and the formation of inflammatory papules and pustules.(8)

Clinical Findings

Rosacea involves a spectrum of clinical findings. Recurrent facial flushing is believed to be one of the major causative factors in rosacea as well as one of its stigmas.(7) One study showed that patients with rosacea flushed more frequently than members of a control population.(5) Facial edema often follows a flushing reaction. In some cases, the edema can take the form of persistent facial lymphedema.

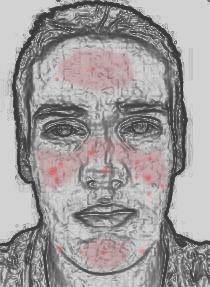

Frequent episodes of flushing represent the first of four stages in the pathogenesis of rosacea. The second stage consists of persistent erythema with telangiectasia, which are dilated superficial veins (Figure 1). In rosacea, telangiectasia often occurs paranasally and on the cheeks. The third stage of rosacea is the development of inflammatory lesions: papules, pustules and nodules (Figure 2). A minority of patients progress to the fourth stage, which is manifested as rhinophyma, a bulbous hypertrophy of the nose resulting from proliferation of sebaceous glands and connective and vascular tissue (Figure 3). This stage occurs more commonly in men than in women.(9) In a study of 108 patients with rosacea (Table 1),(2) 62 percent of patients with lymphedema and 93 percent of patients with rhinophyma were men.

[CHART OMITTED]

TABLE 1 Clinical Findings in Patients with Rosacea

From Sibenge S, Gawkrodger DJ. Rosacea: a study of clinical patterns, blood flow, and the role of Demodex folliculorum. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26:590-3. Used with permission.

A subset of patients with rosacea have facial papules resulting from a granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate in the skin.(3) Clinically, these patients have firm papules with an "apple jelly" color that is also characteristic of granulomatous inflammation found in other conditions, such as cutaneous sarcoid, tuberculosis and leprosy (Figure 4).

[CHART OMITTED]

In addition to the cutaneous problems, rosacea may also cause ocular manifestations, including blepharoconjunctivitis, keratitis and scleritis or episcleritis. The prevalence of ocular involvement in patients with rosacea has been reported to be as low as 3 percent and as high as 58 percent.(10)

Blepharoconjunctivitis is characterized by erythematous eyelid margins that may demonstrate telangiectasia. Conjunctivitis in rosacea can be either a diffuse hyperemic type or a less common nodular variant.(11) The diffuse hyperemic form is characterized by engorged blood vessels of the tarsal and bulbar conjunctivae. In nodular conjunctivitis, small, highly vascularized nodules appear in the interpalpebral area. Keratitis frequently involves the lower portion of the cornea and is associated with pain, photophobia and a sensation of a foreign body in the eye. Corneal involvement commonly presents as punctate epithelial erosions in the inferior half of the cornea.(12)

Differential Diagnosis

Rosacea can be diagnosed in middle-aged to elderly patients who present with facial erythema, a history of flushing, telangiectasias, papules, pustules and, occasionally, nodules or rhinophyma, or any combination of these findings. The medical history should be negative for use of topical corticosteroids and symptoms or signs of sarcoidosis.

Skin conditions that share certain features with rosacea are listed in Table 2. Rosacea can be distinguished from acne vulgaris by the fact that acne tends to affect younger persons and results in the formation of comedones, which are notably lacking in rosacea. Use of topical corticosteroids on the face can result in an acneiform eruption consisting of papules, pustules and comedones that tend to be in the same stage of development--unlike the lesions in acne vulgaris (Figure 5).

[CHART OMITTED]

TABLE 2 Differential Diagnosis of Rosacea

Perioral dermatitis often affects young to middle-aged women and is characterized by the presence of erythema, slight scaling and small papules and pustules involving the central lower one-third of the face. Acneiform eruptions and perioral dermatitis can be inflammatory. Use of topical corticosteroids on the face can aggravate these conditions. When topical corticosteroids are withdrawn, marked exacerbations can occur that are often more severe than the original dermatitis. Figure 6 shows a patient whose perioral dermatitis was exacerbated by the use of topical corticosteroids. These preparations can also cause atrophy of facial skin. Topical corticosteroids that are more potent than hydrocortisone should not be used on the face.

[CHART OMITTED]

Seborrheic dermatitis may begin to involve the face in adulthood and is characterized by erythema, pruritis and yellow, greasy scaling involving the eyebrows, nasolabial folds, retroauricular folds and the presternal area.

The malar erythema ("butterfly rash") of systemic lupus erythematosus can be confused with the background erythema of rosacea, but papules and pustules are not found in systemic lupus.

Granulomatous rosacea is clinically similar in appearance to sarcoid involving the face. A biopsy of the skin may be necessary to differentiate between these two conditions.

Treatment

A variety of therapies have been used in the treatment of rosacea (Table 3). These include the use of oral and topical antibiotics, isotretinoin (Accutane), surgical ablation of telangiectasia and rhinophyma and avoidance of provocative factors. The use of topical metronidazole (MetroGel) and surgery for some of the rosacea stigmas represent more recent developments in this area.

TABLE 3 Treatment of Acne Rosacea

ORAL ANTIBIOTICS

Oral antibiotics have been a mainstay of rosacea therapy. Antibiotic therapy is most effective against inflammatory papules and pustules. The erythema and telangiectasia of rosacea respond minimally to oral antibiotics. Tetracycline, in doses ranging from 250 mg to 1,000 mg per day, is widely used. Other antibiotics used for the treatment of rosacea include erythromycin, minocycline (Dynacin, Minocin), doxycycline (Vibramycin), ampicillin and metronidazole (Flagyl, Protostat). Patients often begin with a higher dose of antibiotic, which is then tapered to a level that maintains control over the development of inflammatory lesions. Relapses are common following withdrawal of antibiotics. To prevent relapses, topical metronidazole may be given in conjunction with oral antibiotics and maintained as the antibiotics are tapered.

The mechanism of action of antibiotics in the treatment of rosacea may be antiinflammatory rather than antibacterial. Tetracyclines and erythromycin have been shown to reduce leukocyte migration and phagocytosis.(13)

In patients treated for acne, adverse effects on the hepatic, renal and hematopoietic systems rarely may be associated with tetracycline, minocycline or erythromycin therapy. Adverse reactions in healthy patients tend to be idiosyncratic; there is no asymptomatic period during which laboratory monitoring could lead to early detection and prevention of the reaction. Current recommendations favor laboratory monitoring in patients with concomitant medical conditions.(14) For example, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine and electrolyte measurements should be monitored when using tetracycline in patients with renal insufficiency. Patients who take erythromycin should be cautioned about the use of terfenadine (Seldane) and astemizole (Hismanal), since erythromycin combined with either of these drugs may induce arrhythmia.

TOPICAL METRONIDAZOLE

A recent development in the treatment of rosacea is the use of topical metronidazole gel. Concerns about gastrointestinal upset and other side effects of long-term oral antibiotic therapy have prompted trials of topical metronidazole in the treatment of rosacea. In a study of 81 patients with rosacea,(15) 1 percent metronidazole cream was found to be superior to placebo for all symptoms except telangiectasia. The improvement in erythema was not statistically significant. Five percent of study subjects using 1 percent metronidazole cream in another study(16) noted skin irritation, dryness and stinging.

In another study,(17) metronidazole was reformulated into an aqueous gel in a concentration of 0.75 percent with a pH of 5.25 in an effort to reduce skin irritation. Two randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled trials of 0.75 percent metronidazole gel and its vehicle demonstrated effectiveness of the active drug, particularly against inflammatory lesions.(18)(19) Erythema also improved, but to a lesser extent than the inflammatory lesions. In a study of 19 patients with recalcitrant rosacea, 84 percent of patients experienced a reduction of at least 50 percent in inflammatory lesions, and 79 percent of patients demonstrated a reduction in severity of erythema.(20)

Like oral metronidazole, the effect of topical metronidazole gel may be anti-inflammatory rather than antimicrobial. In a study investigating the effect of therapeutic concentrations of metronidazole on neutrophil function in vitro, the drug significantly reduced levels of hydrogen peroxide and hydroxyl radicals, which are potent oxidants capable of causing tissue injury at sites of inflammation.(21)

Topical metronidazole does not appear to be absorbed systemically in appreciable amounts.(17) Studies of bioavailability revealed low serum levels of metronidazole.(19) The distribution of metronidazole following topical administration has not been determined.

Topical metronidazole is commercially available as a 0.75 percent gel. With twicedaily application, improvement may be noticed after three weeks of use and should continue for up to nine weeks. Topical metronidazole may be used in combination with other modes of therapy such as oral antibiotics and continued as needed after the antibiotic is tapered.

Topical metronidazole has no known drug interactions. Adverse effects reported with topical metronidazole include local reactions consisting of mild dryness, burning, irritation and stinging, which have occurred in up to 2 percent of patients.(22) As with oral antibiotics, relapses commonly occur when topical metronidazole is discontinued.

ISOTRETINOIN

Isotretinoin is a synthetic retinoid that reduces the size of sebaceous glands and alters keratinization of the skin. It is especially effective against cystic acne, but its use is limited by its side effect profile and teratogenic potential. Recalcitrant cases of rosacea have been treated with isotretinoin in doses of 0.5 mg per kg per day with good results, but the disease may recur after discontinuation of the drug.(23)(24) Studies report improvement in inflammatory lesions, edema and rhinophyma, but little change in erythema.(23)(24)

Side effects of isotretinoin include dryness of the lips and mucous membranes, scaling skin, facial dermatitis, muscular pain, arthralgias, hair loss and elevated blood lipid levels. Isotretinoin is a known teratogen. It is recommended that sexually active women of childbearing age use two forms of contraception and undergo monthly pregnancy testing. This drug should never be prescribed if there is any possibility that the patient cannot follow the recommended guidelines.

SURGERY

Newer developments in the management of rosacea include surgical approaches to some of the rosacea stigmas, including erythema, telangiectasia and rhinophyma. Many vascular skin lesions respond to treatment with a tunable dye laser. When tuned to the wavelength at which blood vessels absorb light, effective treatment of vascular lesions can be accomplished with little scarring or damage to surrounding skin. These treatments can be performed in an outpatient setting under local anesthesia.

In one study,(8) 27 rosacea patients were treated with a flash-lamp--pumped tunable dye laser set at 585 nm. Good or excellent reduction of telangiectasia, erythema and overall appearance was achieved in 24 patients receiving one to three treatments. No scar formation was clinically detectable. Availability of this form of treatment is limited.

In some cases, rhinophyma can result in gross deformity of the nose. Although some individuals may associate rhinophyma with alcoholism, no evidence indicates that alcohol is a causative factor in its development. Surgical treatment of rhinophyma is aimed at the restoration of a more normal contour of the nose while minimizing scar formation. Surgical methods include dermabrasion, excision and skin grafting, scalpel shaving, cryosurgery, electrosurgery and laser. One study compared electrosurgery with carbon dioxide laser treatment of rhinophyma in three patients.(25) The operating time with the laser was twice that of electrosurgery and was more expensive. Wound healing, patient acceptance and the final result were comparable with both treatment modalities.

OCULAR ROSACEA

Treatment of ocular rosacea is directed at management of blepharitis.(26) Oral tetracycline and erythromycin have been found effective in decreasing blepharoconjunctivitis. Topical corticosteroids are helpful in the treatment of iritis, keratitis or episcleritis associated with rosacea, but close followup by an ophthalmologist is required due to the risk of corneal ulceration.

AVOIDANCE OF PROVOCATIVE FACTORS

Avoidance of factors that provoke flushing is important in the management of rosacea. A sunscreen should be used to prevent further damage to the cutaneous blood vessels from ultraviolet light. Women may benefit from the use of a cover-up makeup that has a green tint.(7) This cover-up makeup can be worn under foundation to help mask the underlying erythema of the skin.

REFERENCES

(1.)Klaber R, Wittkower E. The pathogenesis of rosacea: a review with special reference to emotional factors. Br J Dermatol Syphilol 1939; 51:501.

(2.)Sibenge S, Gawkrodger DJ. Rosacea: a study of clinical patterns, blood flow, and the role of Demodex folliculorum. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26: 590-3.

(3.)Helm KF, Menz J, Gibson LE, Dicken CH. A clinical and histopathologic study of granulomatous rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991; 25(6 Pt 1): 1038-43.

(4.)Marks R, Harcourt-Webster JN. Histopathology of rosacea. Arch Dermatol 1969; 100:683-91.

(5.)Marks R. Concepts in the pathogenesis of rosacea. Br J Dermatol 1968; 80:170-7.

(6.)Sobye P. Aetiology and pathogenesis of rosacea. Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh) 1950; 30:137-58.

(7.)Wilkin JK. Rosacea. Int J Dermatol 1983; 22:393-400.

(8.)Lowe NJ, Behr KL, Fitzpatrick R, Goldman M, Ruiz-Esparza J. Flash lamp pumped dye laser for rosacea-associated telangiectasia and erythema. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1991; 17:522-5.

(9.)Rebora A. Rosacea. J Invest Dermatol 1987; 88 (Suppl 3):56S-60S.

(10.)Browning DJ, Proia AD. Ocular rosacea. Surv Ophthalmol 1986; 31:145-58.

(11.)Mondino BJ, Manthey R. Dermatological diseases and the peripheral cornea. Int Ophthalmol Clin 1986; 26:121-36.

(12.)Jenkins MS, Brown SI, Lempert SL, Weinberg RJ. Ocular rosacea. Am J Ophthalmol 1979; 88(3 Pt 2):618-22.

(13.)Esterly NB, Furey NL, Flanagan LE. The effect of antimicrobial agents on leukocyte chemotaxis. J Invest Dermatol 1978; 70:51-5.

(14.)Driscoll MS, Rothe MJ, Abrahamian L, Grant-Kels JM. Long-term oral antibiotics for acne: is laboratory monitoring necessary? J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 28:595-602.

(15.)Nielsen PG. Treatment of rosacea with 1% metronidazole cream. A double-blind study. Br J Dermatol 1983; 108:327-32.

(16.)Veien NK, Christiansen JV, Hjorth N, Schmidt H. Topical metronidazole in the treatment of rosacea. Cutis 1986; 38:209-10.

(17.)Schmadel LK, McEvoy GK. Topical metronidazole: a new therapy for rosacea. Clin Pharm 1990; 9:94-101.

(18.)Bleicher PA, Charles JH, Sober AJ. Topical metronidazole therapy for rosacea. Arch Dermatol 1987; 123:609-14.

(19.)Aronson IK, Rumsfield JA, West DP, Alexander J, Fischer JH, Paloucek FP. Evaluation of topical metronidazole gel in acne rosacea. Drug Intell Clin Pharm 1987; 21:346-51.

(20.)Lowe NJ, Henderson T, Millikan LE, Smith S, Turk K, Parker F. Topical metronidazole for severe and recalcitrant rosacea: a prospective open trial. Cutis 1989; 43:283-6.

(21.)Miyachi Y, Imamura S, Niwa Y. Anti-oxidant action of metrondazole: a possible mechanism of action in rosacea. Br J Dermatol 1986; 114:231-4.

(22.)Nielsen PG. Metronidazole treatment in rosacea. Int J Dermatol 1988; 27:1-5.

(23.)Plewig G, Nikolowski J, Wolff HH. Action of isotretinoin in acne rosacea and gram-negative folliculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1982; 6(4 Pt 2 Suppl): 766-85.

(24.)Hoting E, Paul E, Plewig G. Treatment of rosacea with isotretinoin. Int J Dermatol 1986; 25:660-3.

(25.)Greenbaum SS, Krull EA, Watnick K. Comparison of [CO.sub.2] laser and electrosurgery in the treatment of rhinophyma. J Am Acad Dermatol 1988; 18(2 Pt 1): 363-8.

(26.)Donshik PC, Hoss DM, Ehlers WH. Inflammatory and papulosquamous disorders of the skin and eye. Dermatol Clin 1992; 10(3):533-47.

COPYRIGHT 1994 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group