Definition

Syphilis is an infectious systemic disease that may be either congenital or acquired through sexual contact or contaminated needles.

Description

Syphilis has both acute and chronic forms that produce a wide variety of symptoms affecting most of the body's organ systems. The range of symptoms makes it easy to confuse syphilis with less serious diseases and ignore its early signs. Acquired syphilis has four stages (primary, secondary, latent, and tertiary) and can be spread by sexual contact during the first three of these four stages.

Syphilis, which is also called lues (from a Latin word meaning plague), has been a major public health problem since the sixteenth century. The disease was treated with mercury or other ineffective remedies until World War I, when effective treatments based on arsenic or bismuth were introduced. These were succeeded by antibiotics after World War II. At that time, the number of cases in the general population decreased, partly because of aggressive public health measures. This temporary decrease, combined with the greater amount of attention given to AIDS in recent years, leads some people to think that syphilis is no longer a serious problem. In actual fact, the number of cases of syphilis in the United States has risen since 1980. This increase affects both sexes, all races, all parts of the nation, and all age groups, including adults over 60. The number of women of childbearing age with syphilis is the highest that has been recorded since the 1940s. About 25,000 cases of infectious syphilis in adults are reported annually in the United States. It is estimated, however, that 400,000 people in the United States need treatment for syphilis every year, and that the annual worldwide total is 50 million persons.

The increased incidence of syphilis in recent years is associated with drug abuse as well as changes in sexual behavior. The connections between drug abuse and syphilis include needle sharing and exchanging sex for drugs. In addition, people using drugs are more likely to engage in risky sexual practices. With respect to changing patterns of conduct, a sharp increase in the number of people having sex with multiple partners makes it more difficult for public health doctors to trace the contacts of infected persons. High-risk groups for syphilis include:

- Sexually active teenagers

- People infected with another sexually transmitted disease (STD), including AIDS

- Sexually abused children

- Women of childbearing age

- Prostitutes of either sex and their customers

- Prisoners

- Persons who abuse drugs or alcohol.

The chances of contracting syphilis from an infected person in the early stages of the disease during unprotected sex are between 30-50%.

Causes & symptoms

Syphilis is caused by a spirochete, Treponema pallidum. A spirochete is a thin spiral- or coil-shaped bacterium that enters the body through the mucous membranes or breaks in the skin. In 90% of cases, the spirochete is transmitted by sexual contact. Transmission by blood transfusion is possible but rare; not only because blood products are screened for the disease, but also because the spirochetes die within 24 hours in stored blood. Other methods of transmission are highly unlikely because T. pallidum is easily killed by heat and drying.

Primary syphilis

Primary syphilis is the stage of the organism's entry into the body. The first signs of infection are not always noticed. After an incubation period ranging between 10 and 90 days, the patient develops a chancre, which is a small blister-like sore about 0.5 in (13 mm) in size. Most chancres are on the genitals, but may also develop in or on the mouth or on the breasts. Rectal chancres are common in male homosexuals. Chancres in women are sometimes overlooked if they develop in the vagina or on the cervix. The chancres are not painful and disappear in 3-6 weeks even without treatment. They resemble the ulcers of lymphogranuloma venereum, herpes simplex virus, or skin tumors.

About 70% of patients with primary syphilis also develop swollen lymph nodes near the chancre. The nodes may have a firm or rubbery feel when the doctor touches them but are not usually painful.

Secondary syphilis

Syphilis enters its secondary stage between six to eight weeks and six months after the infection begins. Chancres may still be present but are usually healing. Secondary syphilis is a systemic infection marked by the eruption of skin rashes and ulcers in the mucous membranes. The skin rash may mimic a number of other skin disorders such as drug reactions, rubella, ringworm, mononucleosis, and pityriasis rosea. Characteristics that point to syphilis include:

- A coppery color

- Absence of pain or itching

- Occurrence on the palms of hands and soles of feet.

The skin eruption may resolve in a few weeks or last as long as a year. The patient may also develop condylomata lata, which are weepy pinkish or grey areas of flattened skin in the moist areas of the body. The skin rashes, mouth and genital ulcers, and condylomata lata are all highly infectious.

About 50% of patients with secondary syphilis develop swollen lymph nodes in the armpits, groin, and neck areas; about 10% develop inflammations of the eyes, kidney, liver, spleen, bones, joints, or the meninges (membranes covering the brain and spinal cord). They may also have a flulike general illness with a low fever, chills, loss of appetite, headaches, runny nose, sore throat, and aching joints.

Latent syphilis

Latent syphilis is a phase of the disease characterized by relative absence of external symptoms. The term latent does not mean that the disease is not progressing or that the patient cannot infect others. For example, pregnant women can transmit syphilis to their unborn children during the latency period.

The latent phase is sometimes divided into early latency (less than two years after infection) and late latency. During early latency, patients are at risk for spontaneous relapses marked by recurrence of the ulcers and skin rashes of secondary syphilis. In late latency, these recurrences are much less likely. Late latency may either resolve spontaneously or continue for the rest of the patient's life.

Tertiary syphilis

Untreated syphilis progresses to a third or tertiary stage in about 35-40% of patients. Patients with tertiary syphilis cannot infect others with the disease. It is thought that the symptoms of this stage are a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to the spirochetes. Some patients develop so-called benign late syphilis, which begins between three and 10 years after infection and is characterized by the development of gummas. Gummas are rubbery tumor-like growths that are most likely to involve the skin or long bones but may also develop in the eyes, mucous membranes, throat, liver, or stomach lining. Gummas are increasingly uncommon since the introduction of antibiotics for treating syphilis. Benign late syphilis is usually rapid in onset and responds well to treatment.

Cardiovascular syphilis

Cardiovascular syphilis occurs in 10-15% of patients who have progressed to tertiary syphilis. It develops between 10 and 25 years after infection and often occurs together with neurosyphilis. Cardiovascular syphilis usually begins as an inflammation of the arteries leading from the heart and causes heart attacks, scarring of the aortic valves, congestive heart failure, or the formation of an aortic aneurysm.

Neurosyphilis

About 8% of patients with untreated syphilis will develop symptoms in the central nervous system that include both physical and psychiatric symptoms. Neurosyphilis can appear at any time, from 5-35 years after the onset of primary syphilis. It affects men more frequently than women and Caucasians more frequently than African Americans.

Neurosyphilis is classified into four types:

- Asymptomatic. In this form of neurosyphilis, the patient's spinal fluid gives abnormal test results but there are no symptoms affecting the central nervous system.

- Meningovascular. This type of neurosyphilis is marked by changes in the blood vessels of the brain or inflammation of the meninges (the tissue layers covering the brain and spinal cord). The patient develops headaches, irritability, and visual problems. If the spinal cord is involved, the patient may experience weakness of the shoulder and upper arm muscles.

- Tabes dorsalis. Tabes dorsalis is a progressive degeneration of the spinal cord and nerve roots. Patients lose their sense of perception of one's body position and orientation in space (proprioception), resulting in difficulties walking and loss of muscle reflexes. They may also have shooting pains in the legs and periodic episodes of pain in the abdomen, throat, bladder, or rectum. Tabes dorsalis is sometimes called locomotor ataxia.

- General paresis. General paresis refers to the effects of neurosyphilis on the cortex of the brain. The patient has a slow but progressive loss of memory, ability to concentrate, and interest in self-care. Personality changes may include irresponsible behavior, depression, delusions of grandeur, or complete psychosis. General paresis is sometimes called dementia paralytica, and is most common in patients over 40.

Special populations

Congenital syphilis

Congenital syphilis has increased at a rate of 400-500% over the past decade, on the basis of criteria introduced by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in 1990. In 1994, over 2,200 cases of congenital syphilis were reported in the United States. The prognosis for early congenital syphilis is poor: about 54% of infected fetuses die before or shortly after birth. Those who survive may look normal at birth but show signs of infection between three and eight weeks later.

Infants with early congenital syphilis have systemic symptoms that resemble those of adults with secondary syphilis. There is a 40-60% chance that the child's central nervous system will be infected. These infants may have symptoms ranging from jaundice, enlargement of the spleen and liver, and anemia to skin rashes, condylomata lata, inflammation of the lungs, "snuffles" (a persistent runny nose), and swollen lymph nodes.

Children

Children who develop symptoms after the age of two years are said to have late congenital syphilis. The characteristic symptoms include facial deformities (saddle nose), Hutchinson's teeth (abnormal upper incisors), saber shins, dislocated joints, deafness, mental retardation, paralysis, and seizure disorders.

Pregnant women

Syphilis can be transmitted from the mother to the fetus through the placenta at any time during pregnancy, or through the child's contact with syphilitic ulcers during the birth process. The chances of infection are related to the stage of the mother's disease. Almost all infants of mothers with untreated primary or secondary syphilis will be infected, whereas the infection rate drops to 40% if the mother is in the early latent stage and 6-14% if she has late latent syphilis.

Pregnancy does not affect the progression of syphilis in the mother; however, pregnant women should not be treated with tetracyclines.

HIV patients

Syphilis has been closely associated with HIV infection since the late 1980s. Syphilis sometimes mimics the symptoms of AIDS. Conversely, AIDS appears to increase the severity of syphilis in patients suffering from both diseases, and to speed up the development or appearance of neurosyphilis. Patients with HIV are also more likely to develop lues maligna, a skin disease that sometimes occurs in secondary syphilis. Lues maligna is characterized by areas of ulcerated and dying tissue. In addition, HIV patients have a higher rate of treatment failure with penicillin than patients without HIV.

Diagnosis

Patient history and physical diagnosis

The diagnosis of syphilis is often delayed because of the variety of early symptoms, the varying length of the incubation period, and the possibility of not noticing the initial chancre. Patients do not always connect their symptoms with recent sexual contact. They may go to a dermatologist when they develop the skin rash of secondary syphilis rather than to their primary care doctor. Women may be diagnosed in the course of a gynecological checkup. Because of the long-term risks of untreated syphilis, certain groups of people are now routinely screened for the disease:

- Pregnant women

- Sexual contacts or partners of patients diagnosed with syphilis

- Children born to mothers with syphilis

- Patients with HIV infection

- Persons applying for marriage licenses.

When the doctor takes the patient's history, he or she will ask about recent sexual contacts in order to determine whether the patient falls into a high-risk group. Other symptoms, such as skin rashes or swollen lymph nodes, will be noted with respect to the dates of the patient's sexual contacts. Definite diagnosis, however, depends on the results of laboratory blood tests.

Blood tests

There are several types of blood tests for syphilis presently used in the United States. Some are used in follow-up monitoring of patients as well as diagnosis.

Nontreponemal antigen tests

Nontreponemal antigen tests are used as screeners. They measure the presence of reagin, which is an antibody formed in reaction to syphilis. In the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test, a sample of the patient's blood is mixed with cardiolipin and cholesterol. If the mixture forms clumps or masses of matter, the test is considered reactive or positive. The serum sample can be diluted several times to determine the concentration of reagin in the patient's blood.

The rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test works on the same principle as the VDRL. It is available as a kit. The patient's serum is mixed with cardiolipin on a plastic-coated card that can be examined with the naked eye.

Nontreponemal antigen tests require a doctor's interpretation and sometimes further testing. They can yield both false-negative and false-positive results. False-positive results can be caused by other infectious diseases, including mononucleosis, malaria, leprosy, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus. HIV patients have a particularly high rate (4%, compared to 0.8% of HIV-negative patients) of false-positive results on reagin tests. False-negatives can occur when patients are tested too soon after exposure to syphilis; it takes about 14-21 days after infection for the blood to become reactive.

Treponemal antibody tests

Treponemal antibody tests are used to rule out false- positive results on reagin tests. They measure the presence of antibodies that are specific for T. pallidum. The most commonly used tests are the microhemagglutination-T. pallidum (MHA-TP) and the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) tests. In the FTA-ABS, the patient's blood serum is mixed with a preparation that prevents interference from antibodies to other treponemal infections. The test serum is added to a slide containing T. pallidum. In a positive reaction, syphilitic antibodies in the blood coat the spirochetes on the slide. The slide is then stained with fluorescein, which causes the coated spirochetes to fluoresce when the slide is viewed under ultraviolet (UV) light. In the MHA-TP test, red blood cells from sheep are coated with T. pallidum antigen. The cells will clump if the patient's blood contains antibodies for syphilis.

Treponemal antibody tests are more expensive and more difficult to perform than nontreponemal tests. They are therefore used to confirm the diagnosis of syphilis rather than to screen large groups of people. These tests are, however, very specific and very sensitive; false-positive results are relatively unusual.

Investigational blood tests

As of 1998, ELISA, Western blot, and PCR testing are being studied as additional diagnostic tests, particularly for congenital syphilis and neurosyphilis.

Other laboratory tests

Microscope studies

The diagnosis of syphilis can also be confirmed by identifying spirochetes in samples of tissue or lymphatic fluid. Fresh samples can be made into slides and studied under darkfield illumination. A newer method involves preparing slides from dried fluid smears and staining them with fluorescein for viewing under UV light. This method is replacing darkfield examination because the slides can be mailed to professional laboratories.

Spinal fluid tests

Testing of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is an important part of patient monitoring as well as a diagnostic test. The VDRL and FTA-ABS tests can be performed on CSF as well as on blood. An abnormally high white cell count and elevated protein levels in the CSF, together with positive VDRL results, suggest a possible diagnosis of neurosyphilis. CSF testing is not used for routine screening. It is used most frequently for infants with congenital syphilis, HIV-positive patients, and patients of any age who are not responding to penicillin treatment.

Treatment

Medications

Syphilis is treated with antibiotics given either intramuscularly (benzathine penicillin G or ceftriaxone) or orally (doxycycline, minocycline, tetracycline, or azithromycin). Neurosyphilis is treated with a combination of aqueous crystalline penicillin G, benzathine penicillin G, or doxycycline. It is important to keep the levels of penicillin in the patient's tissues at sufficiently high levels over a period of days or weeks because the spirochetes have a relatively long reproduction time. Penicillin is more effective in treating the early stages of syphilis than the later stages.

Doctors do not usually prescribe separate medications for the skin rashes or ulcers of secondary syphilis. The patient is advised to keep them clean and dry, and to avoid exposing others to fluid or discharges from condylomata lata.

Pregnant women should be treated as early in pregnancy as possible. Infected fetuses can be cured if the mother is treated during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Infants with proven or suspected congenital syphilis are treated with either aqueous crystalline penicillin G or aqueous procaine penicillin G. Children who acquire syphilis after birth are treated with benzathine penicillin G.

Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction

The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, first described in 1895, is a reaction to penicillin treatment that may occur during the late primary, secondary, or early latent stages. The patient develops chills, fever, headache, and muscle pains within two to six hours after the penicillin is injected. The chancre or rash gets temporarily worse. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction, which lasts about a day, is thought to be an allergic reaction to toxins released when the penicillin kills massive numbers of spirochetes.

Alternative treatment

Antibiotics are essential for the treatment of syphilis. Recovery from the disease can be assisted by dietary changes, sleep, exercise, and stress reduction.

Homeopathy

Homeopathic practitioners are forbidden by law in the United States to claim that homeopathic treatment can cure syphilis. Given the high rate of syphilis in HIV-positive patients, however, some alternative practitioners who are treating AIDS patients with homeopathic remedies maintain that they are beneficial for syphilis as well. The remedies suggested most frequently are Medorrhinum, Syphilinum, Mercurius vivus, and Aurum. The historical link between homeopathy and syphilis is Hahnemann's theory of miasms. He thought that the syphilitic miasm was the second oldest cause of constitutional weakness in humans.

Prognosis

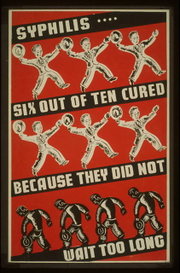

The prognosis is good for the early stages of syphilis if the patient is treated promptly and given sufficiently large doses of antibiotics. Treatment failures can occur and patients can be reinfected. There are no definite criteria for cure for patients with primary and secondary syphilis, although patients who are symptom-free and have had negative blood tests for two years after treatment are usually considered cured. Patients should be followed up with blood tests at one, three, six, and 12 months after treatment, or until the results are negative. CSF should be examined after one year. Patients with recurrences during the latency period should be tested for reinfection.

The prognosis for patients with untreated syphilis is spontaneous remission for about 30%; lifelong latency for another 30%; and potentially fatal tertiary forms of the disease in 40%.

Prevention

Immunity

Patients with syphilis do not acquire lasting immunity against the disease. As of 1998, no effective vaccine for syphilis has been developed. Prevention depends on a combination of personal and public health measures.

Lifestyle choices

The only reliable methods for preventing transmission of syphilis are sexual abstinence or monogamous relationships between uninfected partners. Condoms offer some protection but protect only the covered parts of the body.

Public health measures

Contact tracing

The law requires reporting of syphilis cases to public health agencies. Sexual contacts of patients diagnosed with syphilis are traced and tested for the disease. This includes all contacts for the past three months in cases of primary syphilis and for the past year in cases of secondary disease. Neither the patients nor their contacts should have sex with anyone until they have been tested and treated.

All patients who test positive for syphilis should be tested for HIV infection at the time of diagnosis.

Prenatal testing of pregnant women

Pregnant women should be tested for syphilis at the time of their first visit for prenatal care, and again shortly before delivery. Proper treatment of secondary syphilis in the mother reduces the risk of congenital syphilis in the infant from 90% to less than 2%.

Education and information

Patients diagnosed with syphilis should be given information about the disease and counseling regarding sexual behavior and the importance of completing antibiotic treatment. It is also important to inform the general public about the transmission and early symptoms of syphilis, and provide adequate health facilities for testing and treatment.

Key Terms

- Chancre

- The initial skin ulcer of primary syphilis, consisting of an open sore with a firm or hard base.

- Condylomata lata

- Highly infectious patches of weepy pink or gray skin that appear in the moist areas of the body during secondary syphilis.

- Darkfield

- A technique of microscope examination in which light is directed at an oblique angle through the slide so that organisms look bright against a dark background.

- General paresis

- A form of neurosyphilis in which the patient's personality, as well as his or her control of movement, is affected. The patient may develop convulsions or partial paralysis.

- Gumma

- A symptom that is sometimes seen in tertiary syphilis, characterized by a rubbery swelling or tumor that heals slowly and leaves a scar.

- Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction

- A temporary reaction to penicillin treatment for syphilis that includes fever, chills, and worsening of the skin rash or chancre.

- Lues maligna

- A skin disorder of secondary syphilis in which areas of ulcerated and dying tissue are formed. It occurs most frequently in HIV-positive patients.

- Spirochete

- A type of bacterium with a long, slender, coiled shape. Syphilis is caused by a spirochete.

- Tabes dorsalis

- A progressive deterioration of the spinal cord and spinal nerves associated with tertiary syphilis.

Further Reading

For Your Information

Books

- Fiumara, Nicholas J. "Syphilis." In Conn's Current Therapy, edited by Robert E. Rakel. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company, 1998.

- "Infectious Diseases: Syphilis." In Neonatology: Management, Procedures, On-Call Problems, Diseases and Drugs, edited by Tricia Lacy Gomella, et al. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange, 1994.

- Jacobs, Richard A. "Infectious Diseases: Spirochetal." In Current Medical Diagnosis & Treatment 1998, edited by Lawrence M. Tierney, Jr. et al., Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange, 1998.

- Ramin, Susan M., et al. "Sexually Transmitted Diseases and Pelvic Infections." In Current Obstetric & Gynecologic Diagnosis & Treatment, edited by Alan H. DeCherney, and Martin L. Pernoll. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lange, 1994.

- "Sexually Transmitted Diseases: Syphilis." In The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy, vol. II, edited by Robert Berkow, et al. Rahway, NJ: Merck Research Laboratories, 1992.

- Sigel, Eric J. "Sexually Transmitted Diseases." In Current Pediatric Diagnosis & Treatment, edited by William W. Hay, Jr., et al. Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange, 1997.

- "Syphilis." In Professional Guide to Diseases, edited by Stanley Loeb, et al. Springhouse, PA: Springhouse Corporation, 1991.

- Wicher, Konrad, and Victoria Wicher. "Treponema, Infection and Immunity." In Encyclopedia of Immunology, vol. III, edited by Ivan M. Roitt, and Peter J. Delves. London: Academic Press, 1992.

- Wolf, Judith E. "Syphilis." In Current Diagnosis 9, edited by Rex B. Conn, et al. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company, 1997.

Organizations

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1600 Clifton Road NE, Atlanta, GA, 30333. (404) 639-3534.

Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Gale Research, 1999.