Angiostrongylus costaricensis (classified under the more specific genus Parastrongylus by different authors) is a filiform intestinal nematode endemic to Central and South America, which afflicts primarily the pediatric population 1 to 13 years of age. Only three cases of adult infections have been previously documented outside the endemic region. To our knowledge, we report the first such case in the western United States, as well as the oldest patient yet recorded. Our patient is a 73-year-old woman living in Los Angeles who presented with an acute abdomen 4 weeks following a 5-month visit to El Salvador. Examination of the gross ileum removed at exploratory laparotomy revealed a perforation associated with a segmentally thickened intestinal wall. Microscopic examination showed eosinophilic ileitis, arterial lumens containing nematodes morphologically consistent with A costaricensis, eggs in the submucosa, and arteriolitis with thrombosis. (Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997;121:989-991 )

Angiostrongylus (Parastrongylus)l costaricensis is a metastrongylid intestinal nematode found primarily in snails and veronicellid slugs, the obligatory intermediate hosts, and rodents (Sigmodon hispidus, Rattus rattus, and other species), the definitive host.2 Man, an accidental host, may ingest the infectious larvae, causing human abdominal angiostrongylosis, which is most frequently characterized by ileocecal or appendiceal eosinophilia, with rare lymph node, liver, or testicle involvement.35 Abdominal angiostrongylosis is primarily a pediatric ailment in Central and South America. In Costa Rica up to 600 patients are newly diagnosed annually67 (oral communication, P Morera, PhD, August 1996).

Angiostrongylosis is uncommon in adults in Costa Rica and is extremely rare outside the endemic region. To our knowledge, only three previous cases have been reported.4,8,9 Here we describe a fourth case, which resulted in eosinophilic ileitis with perforation.

REPORT OF A CASE

A 73-year-old woman, who was a native of El Salvador and had immigrated to the United States 3 years prior to this admission, presented to Harbor-University of California at Los Angeles Medical Center following 1 day of acute, severe, diffuse abdominal pain following 2 weeks of right upper quadrant and suprapubic pain. The patient reported fever, chills, nausea, and two episodes of loose stool associated with severe right lower quadrant pain. She denied melena, hematochezia, dysuria, hematuria, or gynecologic symptoms. Past medical history and social history were noncontributory and revealed no risk factors for immune deficiency. The patient had returned to her home town, Puerto de Acahutla, El Salvador, twice. Her last tour in El Salvador had lasted from 6 months prior to admission to 1 month prior. She ate raw leafy vegetables and fresh fruits regularly during her stay there. Family history was unremarkable.

Physical examination showed a febrile alert woman with a distended, diffusely tender abdomen with guarding. No mass was palpable, a stool guaiac test was negative, and pelvic examination showed only mild uterine prolapse. The patient's white blood cell count at admission was 22 x 10^sup9^/L with a differential count that included 0.21 band neutrophils and 0.42 eosinophils. An exploratory laparotomy was performed on admission. The distal ileum was found to be perforated and was resected. The patient's symptoms improved and, 1 week postoperatively, her white blood cell count decreased to 12 x 10^sup9^/L and her differential showed 0.04 eosinophils. Chemistries, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time were unremarkable. No fecal leukocytes, ova, or parasites were observed, and stool cultures were negative. She was started on an antihelminthic therapeutic regimen with thiabendazole.3 She has been asymptomatic since her discharge.

PATHOLOGIC FINDINGS

The specimen was a section of small bowel without cecum or appendix measuring 38 cm in length. The lumen was empty on gross examination. Examination of ileal mucosa revealed a 1.0 x 0.2-cm perforation located in the approximate center of a circular flattened region devoid of mucosal folds measuring 2.0 cm in diameter. The mucosal surface was mildly dusky, and grey-red fibrinous debris were attached to the serosal surface. Serial sections showed a thickened bowel wall, which measured up to 1.2 cm (Fig 1), containing occasional small red puncta. The mesentery and lymph node dissections were unremarkable.

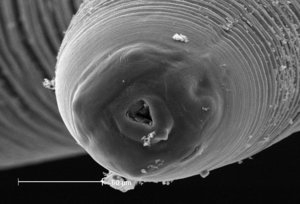

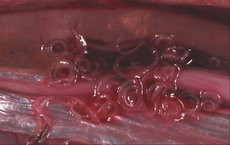

Microscopic examination showed intense eosinophilic inflammatory infiltrate throughout the entire thickness of the intestinal wall. A dead nematode was found immediately adjacent to the perforation site (Fig 2). Worms characterized morphologically by thin (2- to 3-,am) keratin cuticles, a lack of lateral chords, and intestines lined by cuboidal to low columnar cells were located within arterial lumens of the intestinal wall (Fig 3). The worm eggs were ovoid, located within the submucosa, and possessed thin, pale eosinophilic shells (Fig 4). Multiple microangiopathy and arterial thromboses were found (Fig 5), along with occasional giant cells and rare, poorly developed granulomas. Microscopic examination of the lymph nodes and mesentery vessels was unremarkable.

COMMENT

Differential diagnosis for gastrointestinal eosinophilia is wide-ranging (Table). Parasitic infections, specifically helminths, considered in the differential diagnosis in our patient included Trichuris trichiura, which resides within the cecum and colon with the slender anterior portion of the worm embedded in the mucosal epithelium. In gastrointestinal schistosomiasis, the adult worms are found in the venous system. Ova deposited by the female worms may produce granulomas that progress to fibrosis and, in some instances, polyp formation. Anisakiasis occurs more often in the stomach but may involve the small intestine, especially the terminal ileum. Species of the genera Anisakis and Pseudoterranova are the most common cause of this infection. These larval nematodes may be similar in size to the adults of A costaricensis but can be distinguished by their thick multilayered cuticles, large Y-shaped lateral chords, and intestine lined by tall columnar cells?'o Adult female Strongyloides live in the mucosal epithelium and intestinal crypts, usually in the duodenum and proximal small intestines, and measure only 30 to 40 Jim in diameter. Eggs containing mature rhabditiform larvae are often seen in tissues adjacent to the adult worms.

Human abdominal angiostrongylosis was identified in 1971(11)as the cause of a clinical syndrome that initially had been described in Costa Rican children in 1952.7 The infection is found in rodents in Mexico, Central and South America, and Texas. Human disease has been reported from Honduras, El Salvador, Peru, Nicaragua, Panama, Martinique, Brazil, Guadaloupe, Argentina, Venezuela, Columbia, Guatemala, and Mexico.lz Rare human infections have been reported in Spain4 and the United Statess9 (excluding Puerto Rico), and one possible case was reported in Zaire.13 One report of indigenous infections in the United States14 was subsequently shown to be anisakiasis.10

The life cycle of A costaricensis has been well described,2 its morphology completely characterized,15 and the clinical presentation among the pediatric population thoroughly analyzed.3 Angiostrongylus costaricensis adult worms are found in the cecal and mesenteric arteries of the definitive hosts, cotton rats (Sigmodon hispidus), and other rodent species (Rattus rattus and others). Fertilized eggs embolize to the capillary endothelium, where they penetrate and occupy the subendothelium in submucosal regions. The eggs embryonate, and first-stage larvae hatch from the eggs, migrate through the mucosa, and pass into the lumen to be excreted in the feces. Snails and veronicellid slugs, the obligatory intermediate hosts, ingest the larvae in rodent feces. The ingested first-stage larvae develop in the digestive tract of the mollusk into second-, then thirdstage larvae, which are infectious to certain rodents, monkeys, and humans. Third-stage larvae may also be found in mollusk mucous, and consumption of contaminated raw vegetation may result in human infection. Theoretically, mucous-containing infectious larvae could be ingested by children playing on or with contaminated vegetation, thereby partially contributing to the high rate of indigenous pediatric morbidity. The ingested third-stage larvae migrate to the definitive host's gastrointestinal tract, penetrate the ileocecal mucosa, enter the lymphatics, and mature into adult worms. Adult worms then burrow into the mesenteric arteries, where they mate and complete the cycle. The time interval from possible date of ingestion to onset of symptoms has been documented from 14 days3 to 38 months.8 Our patient most likely had an incubation period of less than 6 months, although this interval may have been greater than 30 months.

Angiostrongylus costaricensis eggs and larvae elicit a strong inflammatory response in the ileocecal submucosa of humans, an accidental host, creating granulation tissue and marked eosinophilia. The eggs are trapped but may undergo further development, sometimes reaching the first larval stage.zs To our knowledge, however, no larva has ever been documented in human feces. Granulation tissue formation, worm embolism, arteriolitis, and thromboembolism may all damage the bowel wall, causing perforation, as described in our patient and others,33 or producing partial intestinal wall necrosisl3 or recurrent gastrointestinal hemorrhage.7

The authors sincerely thank Pedro Morera, PhD, and Lawrence Ash, PhD, for their invaluable suggestions.

References

1. Ubelaker JE. Systematics of species referred to the genus Angiostrongylus. J Parasitol.1986;72:237-244.

2. Morera P. Life history and redescription of Angiostrongy(us costaricensis Morera and Cespedes, 1971. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1973;22:613-621. 3. Loria-Cortes R, Lobo-Sanahuja JR Clinical abdominal angiostrongylosis: a study of 116 children with intestinal eosinophilic granuloma caused by Angiostrongylus costaricensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1980;29:538-544.

4. Vazquez JJ, Boils PL, Sola JJ, et al. Angiostrongyliasis in a European patient: a rare cause of gangrenous ischemic enterocolitis. Gastroenterology.1993;105: 1544-1549.

5. Vazquez JJ, Sola JJ, Boils PL. Hepatic lesions induced by Angiostrongylus costaricensis. Histopathology 1994;25:489 491. 6. Morera P. Abdominal angiostrongyliasis. In: Strickland GT, ed. Hunter's Tropical Medicine. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1991:771-773.

7. Frenkel JK. Angiostrongylus costaricensis infections. In: Binford CH, Connor DH, eds. Pathology of Tropical and Extraordinary Diseases, It. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1976:452-454.

8. Silvera CT, Ghali VS, Roven S, Heimann J, Gelb A. Angiostrongyliasis: a rare cause of gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Am] Gastroenterol.1989;84:329-332. 9. Neafie RC, Marty AM. Unusual infections in humans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1993;6:34-56.

10. Ash LR. Human anisakiasis misdiagnosed as abdominal angiostrongyliasis. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:332-334. Letter and comment. 11. Morera P, Cespedes R. Angiostrongy(us costaricensis n. sp. (Nematoda; Metastrongloideai, a new lungworm occurring in man in Costa Rica. Rev Biol Trop.1971;18:173-185.

12. Pena GP, Andrade Filho J, Assis SC. Angiostrongylus costaricensis: first record of its occurrence in the state of Espirito Santo, Brazil, and a review of its geographic distribution. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo.1995;37:369-374.

13. Baird JK, Neafie RC, Lanoie L, Connor DH. Abdominal angiostrongylosis in an African man: case study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1987;37:353-356. 14. Hulbert TV, Larsen RA, Chandrasoma PT. Abdominal angiostrongyliasis mimicking acute appendicitis and Meckel's diverticulum: report of a case in the United States and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:836-840.

15. Graeff-Teixeira C, Camillo-Coura L, Lenzi HL. Histopathological criteria for the diagnosis of abdominal angiostrongyliasis. Parasitol Res. 1991;77:606611.

Accepted for publication January 27, 1997.

From the Departments of Pathology (Drs Wu and French) and Medicine (Dr Turner), Harbor-University of California at Los Angeles Medical Center.

Reprint requests to Department of Pathology, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, 1000 W Carson St, Torrance, CA 90509 (Dr Wu).

Copyright College of American Pathologists Sep 1997

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved