The incidence of aortic dissection ranges from 5 to 30 cases per million people per year, depending on the prevalence of risk factors in the study population. Although the disease is uncommon, its outcome is frequently fatal, and many patients with aortic dissection die before presentation to the hospital or prior to diagnosis. While pain is the most common symptom of aortic dissection, more than one-third of patients may develop a myriad of symptoms secondary to the involvement of the organ systems. Physical findings may be absent or, if present, could be suggestive of a diverse range of other conditions. Keeping a high clinical index of suspicion is mandatory for the accurate and rapid diagnosis of aortic dissection. CT scanning, MRI, and transesophageal echocardiography are all fairly accurate modalities that are used to diagnose aortic dissection, but each is fraught with certain limitations. The choice of the diagnostic modality depends, to a great extent, on the availability and expertise at the given institution. The management of aortic dissection has consisted of aggressive antihypertensive treatment, when associated with systemic hypertension, and surgery. Recently, endovascular stent placement has been used for the treatment of aortic dissection in select patient populations, but the experience is limited. The technique could be an option for patients who are poor surgical candidates, or in whom the risk of complications is gravely high, especially so in the patients with distal dissections. The clinical, diagnostic, and management perspectives on aortic dissection and its variants, aortic intramural hematoma and atherosclerotic aortic ulcer, are reviewed.

Key words: acute aortic syndrome; aortic dissection; aortic intramural hematoma; atherosclerotic aortic ulcer; clinical features; diagnosis; dissecting aneurysm; dissecting hematoma; prognosis; treatment

Abbreviations: dP/dt = first derivative of pressure; TEE = transesophageal echocardiography; TYE = transthoracic echocardiography

**********

The estimated incidence of aortic dissection is 5 to 30 cases per million people per year. This incidence is related to the prevalence of the risk factors for aortic dissection in different study populations. (1-4) Complications often occur randomly, and the outcome is frequently fatal. Many patients with aortic dissection die before presentation to a hospital or prior to diagnosis. The symptoms of aortic dissection may mimic myocardial ischemia, and physical findings in aortic dissection may be absent or, if present, could be suggestive of a diverse range of other conditions. Therefore, keeping a high clinical index of suspicion is crucial in establishing the diagnosis of aortic dissection. The diagnosis of aortic dissection has been missed in up to 38% of patients on initial evaluation, and in up to 28% of patients the diagnosis has been first established at the post mortem examination. (1-3)

CLASSIFICATION

Aortic dissection is divided into acute and chronic types, depending on the duration of symptoms. Acute aortic dissection is present when the diagnosis is made within 2 weeks after the initial onset of symptoms, and chronic aortic dissection is present when the initial symptoms are of > 2 weeks duration. About one third of patients with aortic dissection fall into the chronic category. (2) The most common site of initiation of aortic dissection is the ascending aorta (50%) followed by the aortic regions in the vicinity of the ligamentum arteriosum. Anatomically, aortic dissection has been classified by two schemes. The DeBakey classification consists of the following three types: I, both the ascending and the descending aorta are involved; II, only the ascending aorta is involved; and III, only the descending aorta is involved. (5) The Stanford classification consists of the following two types: type A, involving the ascending aorta regardless of the entry site location; and type B, involving the aorta distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery. (6) Many cases of aortic dissection do not fit into these classification schemes. For example, a dissection limited to the aortic arch proximal to the origin of the left subclavian artery, but not involving the ascending aorta, would not be classified as type A or B. Therefore, it would be prudent to simplify the classification of aortic dissection into proximal and distal types. Proximal aortic dissection would be composed of the involvement of the aorta proximal to the origin of the left subclavian artery, which may or may not involve aortic segments distal to that point, and distal aortic dissection would be composed of the dissection limited to the aortic segments distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery and not involving the aorta proximal to that point.

PREDISPOSING FACTORS

Men are more frequently affected by aortic dissection, and a male/female ratio ranging from 2:1 to 5:1 has been reported in different series. (7-10) The peak age for the occurrence of proximal dissection is between 50 and 55 years, and that of distal dissection is between 60 and 70 years. Chronic systemic hypertension is the most common factor predisposing the aorta to dissection and has been present in 62 to 78% of patients with aortic dissection. (1,2,11) At the initial presentation, it is more common in patients with proximal dissection than in those with distal dissection (70% vs 35%). Aortic diseases, such as aortic dilatation, aortic aneurysm, anuloaortic ectasia, chromosomal aberrations (eg, Turner syndrome and Noonan syndrome), aortic arch hypoplasia, coarctation of the aorta, aortic arteritis, bicuspid aortic valve, and hereditary connective tissue diseases (eg, Marfan syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome), are well-established predisposing factors for the development of aortic dissection. (4,12) Marfan syndrome accounts for the majority of cases of aortic dissection in patients < 40 years of age.

Direct iatrogenic trauma to the aorta that is inflicted during arterial cannulation for cardiac surgery or during catheter-based diagnostic and therapeutic interventions accounts for about 5% cases of aortic dissection. (13,14) The majority of iatrogenic dissections have been reported in the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta. (13,14) Reports (13) suggest a relationship between the severity of atherosclerosis and the risk of developing an iatrogenic dissection. In these cases, dissection may be initiated by catheter-related injury to the intima, which may previously have been weakened by atherosclerosis. On the other hand, aortic atherosclerosis does not appear to pose a high risk for classic spontaneous aortic dissection, but the development of its two variants, aortic intramural hematoma and atherosclerotic aortic ulcer, is strongly associated with the presence and severity of atherosclerosis. (15) Indirect trauma, such as sudden deceleration, also may result in dissection of the aorta.

Cocaine has been recognized as a cause of aortic dissection in otherwise healthy normotensive individuals. (16,17) The proposed mechanism of aortic dissection during cocaine abuse is mediated through catecholamine-induced, acute, profound elevation of the BP, causing a rapid rise in the first derivative of pressure (dP/dt) on the aortic wall resulting in an intimal tear. Rebound acute elevation of BP secondary to the abrupt discontinuation of [beta]-blocker therapy has also been reported as a cause of aortic dissection, the mechanism of which could be the same as that of the cocaine-induced aortic dissection. (18) The risk of aortic dissection increases in the presence of pregnancy. In women < 40 years of age, 50% of aortic dissections occur during pregnancy. Hypertension has been reported in 25 to 50% of cases of aortic dissection in pregnant women. The most common site of pregnancy-associated aortic dissection is the proximal aorta, and intimal tearing originates within 2 cm of the aortic valve in 75% of cases. The aortic rupture commonly occurs during the third trimester or during the first stage of labor.

PATHOGENESIS

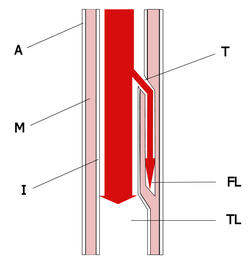

Aortic dissection can result from intimal rupture followed by cleavage formation and propagation of the dissection into the media, or from intramural hemorrhage and hematoma formation in the media subsequently followed by perforation of the intima. (7) The rupture of the intima is the initial event in most cases of dissection. (7) The presence of an intimal flap is the most characteristic feature of aortic dissection (Fig 1). The pathogenesis of dissection is complex. Reports (19,20) have suggested that medial degeneration of the wall of the aorta predispose it to dissection by decreasing the cohesiveness of the layers of the aortic wall. The medial degeneration tends to be more extensive in older individuals and in patients with hypertension, Marfan syndrome, and bicuspid aortic valves. (19,20)

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

There is substantial physiologic evidence to suggest that intimal tears occur in the regions of the aorta that are subjected to the greatest dP/dt and pressure fluctuations. (19) The repeated motion of the aorta related to the contractile function of the heart results in flexion stress, which is most marked in the ascending aorta and in the first portion of the descending thoracic aorta, and these two sites are the most common sites for the initiation of an intimal tear. Furthermore, the hydrodynamic forces in the bloodstream that are generated by the propagation of a pulse wave and the generation of systolic BP during each cardiac cycle deliver kinetic energy to the aortic wall (most markedly to the ascending aorta) during the systolic flow. A portion of this kinetic energy is stored in the aortic wall as potential energy, which then is used to propagate blood flow in the aorta during the diastolic phase of the cardiac cycle. The magnitude of the hydrodynamic forces in the bloodstream is related to the mean BP and the dP/dt, which represents the steepness of the pulse wave. A combination of these factors eventually results in an intimal tear and the propagation of dissection into the media of the aortic wall, especially so in patients with medial degeneration.

Aortic intramural hematoma is characterized by aortic wall hematoma without a demonstrable intimai flap (Fig 2). (20-24) About 8 to 15% of cases of acute aortic syndrome are of intramural hematoma. The rupture of the vasa vasorum in the aortic wall is the most likely cause of the development of aortic intramural hematoma, which is contrary to most cases of aortic dissection in which the intimal rupture precedes the intramural cleavage in the previously weakened aortic media. (25) An intramural hematoma also may result around the crater of a penetrating atherosclerotic aortic ulcer and may propagate into the media (Fig 3). Intramural hematoma formation is more common in the descending thoracic aorta. It can perforate through the intima and transform into a frank aortic dissection. Older, hypertensive patients with diffuse atherosclerosis are more prone to develop aortic intramural hematomas.

[FIGURES 2-3 OMITTED]

Penetrating atherosclerotic aortic ulcers typically occur in elderly patients who have histories of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and severe aortic atherosclerosis. (26) These ulcers are most common in the descending thoracic aorta. They are characterized by a discrete ulcer crater and by a thickened underlying aortic wall (Fig 3). Progressive penetration deep into the aortic wall may result in an intramural hematoma and a weakening of the aortic wall, which, in turn, may result in aortic enlargement and aneurysm formation. (27) Spontaneous healing of the ulcer and resolution of the associated intramural hematoma may cause remodeling in the aortic wall, which also may result in aortic dilatation.

NATURAL HISTORY

The natural history of aortic dissection is poorly understood. Earlier information on aortic dissection was gained mostly from autopsy studies, while newer clinical or pathologic studies came from large referral centers and were based on selected nonconsecutive cases. (1) Acutely, the hydrodynamic forces in the bloodstream continue the propagation of the dissection in the media at varying depths until a rupture occurs either into the lumen of the aorta, resulting in the reduplication of the aortic lumen, or out through the adventitia of the aorta, causing death. Aortic dissection in the ascending aorta is usually to the right and posterior just above the level of the right coronary artery ostium. As a dissecting hematoma advances into the arch of the aorta, it passes posteriorly and superiorly. The dissection is most common posterior and to the left in the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta, resulting in a higher incidence of involvement of the left renal and the left iliofemoral arteries than of those of the right.

According to the results of a population-based longitudinal study on the epidemiology and clinicopathology of aortic dissection by Meszaros et al, (28) 21% of patients with aortic dissections die before hospital admission. The mortality rate for patients with untreated proximal aortic dissections has been reported to increase by 1 to 3% per hour after presentation and is approximately 25% during the first 24 h after the initial presentation, 70% during the first week, and 80% at 2 weeks. (9,14,29) Less than 10% of untreated patients with proximal aortic dissections live for 1 year, and almost all patients die within 10 years. (28) Most of these deaths occur within the first 3 months. According to earlier data (collected from six series) reported by Anagnostopoulos et al (30) on 963 untreated patients with aortic dissections, 90% died within 3 months of presentation with the condition. Death usually is caused by acute aortic regurgitation, major branch vessel obstruction, or aortic rupture. The risk of the fatal aortic rupture in patients with untreated proximal aortic dissections is around 90%, and 75% of these ruptures take place in the pericardium, the left pleural cavity, and the mediastinum. (31)

The natural history of aortic intramural hematoma is similar to that of the classic aortic dissection. The morbidity and mortality of patients with aortic intramural hematoma depends on the site of aortic involvement. (32-36) An aortic intramural hematoma may cause an intimal rupture and transform into a frank aortic dissection. Besides resulting in an intimal tear and transforming into a dissection, an aortic intramural hematoma can penetrate deep into the layers of the aortic wall, resulting in a rupture or pseudoaneurysm of the aorta. The prevalence of fluid extravasation into the pericardial, pleural, or mediastinal space is high and indicates impending aortic rupture. (37) Spontaneous resolution of an aortic intramural hematolna also has been reported. (38)

The natural history of atherosclerotic aortic ulcers is of progressive penetration into the internal elastic lamina and media with a propensity toward aortic dilatation and aneurysm formation. (26) Further progressive penetration of theses ulcers also may result in aortic dissection, aortic rupture, and pseudoaneurysm formation. Aortic dissection is an uncommon consequence of the atherosclerotic aortic ulceration, even though reports have described rare initiation of an aortic dissection at the base of an aortic atherosclerotic ulcer. (39,40) While some degree of hematoma occurs around most atherosclerotic aortic ulcers, propagation to frank dissection is prevented, probably because of the extensive fibrosis of the aortic wall from long-standing atherosclerosis. (22) On long-term follow-up, atherosclerotic aortic ulcers tend to cause aortic dilatation and aneurysm formation more than frank aortic dissections. A free transmural rupture of the aorta is rare. Similarly, a thromboembolism resulting from atherosclerotic aortic ulcers is also rare. (26)

MANIFESTATIONS

Pain in Aortic Dissection

Pain is the most common presenting symptom of aortic dissection. The pain of an aortic dissection is midline and is experienced in the front and back of the trunk, depending on the location of the dissection. The onset of pain is typically catastrophic, and it reaches a maximum level suddenly. The pain could be sharp, ripping, tearing, or knife-like in nature, but the abruptness is the most specific characteristic of the pain. The pain of aortic dissection does not commonly radiate into the neck, shoulder, or arm, as is typical of the pain of an acute coronary syndrome. According to a report (1) on 464 patients from the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection, 95% of patients reported any pain, and 85% reported an abrupt onset. Sharp pain was reported by 64% of patients, whereas the classic tearing or ripping type of pain was reported by 51% of patients. The most common site of pain was the chest (73%), with anterior location being more common than the posterior location (61% vs 36%, respectively). Back pain was experienced by 53% of patients, and abdominal pain was experienced by 30% of patients.

Patients with dissections of the ascending aorta and arch more frequently experience anterior chest pain, whereas patients with dissections of the descending aorta more frequently experience posterior chest, back, and abdominal pain. Extension of the pain down to the back, abdomen, hips, and legs indicates the extension of the dissection process distally. According to a published analysis, (41) the physicians' index of suspicion was highest (86%) in patients who presented with both chest and back pain, followed by those with chest pain (45%) and abdominal pain (8%). The aortic dissection also has been diagnosed on an incidental imaging study, such as transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), CT scan, or MRI that were performed for other reasons. (42-44) There is a possibility that the pain in these patients could have been minimal, and may have been ignored, or that the dissection could have been truly silent. The initial pain of aortic dissection may be followed by a pain-free interval lasting from hours to days, ending with the return of pain. This return of pain after a pain-free interval is an ominous sign and usually indicates an impending rupture. (28)

Manifestations Secondary to Organ System Involvement

More than one third of the patients with aortic dissections demonstrate signs and symptoms secondary to organ system involvement. (45) The most common mechanism of organ system involvement is the development of ischemia caused by the obstruction of branch arteries originating from the aorta. A branch vessel obstruction could be due to an extension of the dissection process into the wall of the artery or due to a direct compression of the artery by an expanding false lumen. Another mechanism of organ system involvement in the process of aortic dissection is the direct compression of a surrounding organ by the expanding false lumen of the dissection. Compressive manifestations are more prone to take place in cases in which the false lumen is not decompressed by a distal intimal tear and results in an expanding blind loop. A third mechanism of organ system involvement in patients with aortic dissection is a leak or rupture of the dissection process into the surrounding structures, which is usually rapidly fatal. The two most commonly involved organ systems in the process of aortic dissection are the cardiovascular and neurologic systems.

Cardiovascular Involvement: Aortic regurgitation (of any degree) accompanies 18 to 50% of cases with proximal aortic dissection. (11,46) A diastolic murmur of aortic regurgitation has been reported in about 25% of patients. Acute, severe aortic regurgitation is the second most common cause of death (after aortic rupture) in patients with aortic dissections. Patients with this condition usually present with acute cardiac decompensation and shock. (3) The mechanisms of aortic regurgitation in aortic dissection include dilatation of the aortic root and annulus, tearing of the annulus or valve cusps, downward displacement of one cusp below the line of the valve closure (due to pressure from an asymmetric false lumen), loss of support of the cusp, and physical interference in the closure of the aortic valve by an intimal flap.

Although most patients with aortic dissections have hypertension at the time of presentation, an initial systolic BP < 100 mm Hg has been reported in about 25% of patients with aortic dissections. Hypotension and shock in patients with aortic dissections are caused by acute severe aortic regurgitation, aortic rupture, cardiac tamponade, or left ventricular systolic dysfunction. (47,48) A rupture or leak of the dissection process into the pericardial cavity may result in acute pericardial effusion/cardiac tamponade and death. (48) Nevertheless, in most cases of aortic dissection, the development of a pericardial effusion is not secondary to the rupture or leak of the dissection into the pericardial cavity, rather it is due to the transudation of fluid into the pericardial cavity through the intact wall of the false lumen. (49) Although the presence of pericardial effusion in patients with aortic dissections is not always secondary to the rupture or leak of the dissection process into the pericardial cavity, the presence of any pericardial effusion may be a very ominous sign and should be taken seriously.

Left ventricular regional wall motion abnormalities are seen in 10 to 15% of patients with aortic dissections and are primarily caused by low coronary perfusion. The presence of low coronary perfusion in patients with aortic dissections could be secondary to the compression of a coronary artery by the expansion of a false lumen, the extension of the dissection process into a coronary artery, hypotension, or a combination of these conditions. (4) Involvement of the right coronary artery is more common than that of the left one, and occasionally dissection and myocardial infarction occur concomitantly. (46) Myocardial ischemia with resultant left ventricular systolic dysfunction is a factor contributing to the development of hypotension and shock in patients with aortic dissections.

A myriad of manifestations develop due to pressure of the false lumen or its rupture into the surrounding cardiac chambers or great vessels. (50,51) The pulse deficits reported in patients with aortic dissections include a significant difference in the pulse volume (ie, pulse differentials) and BP (ie, BP differentials) in two upper extremities or a sudden loss of a pulse. The presence of pulse differentials is the most specific physical sign of aortic dissection, and it has been reported in 38% of patients with aortic dissections. (52) Pulse and BP differentials indicate the partial compression of one or both subclavian arteries. Due to the partial compression or the presence of oscillating flaps, bruits may be present over major arteries, such as the carotid, subclavian, and femoral arteries. Symptomatic ischemia of an extremity, mostly lower extremities, has been reported in 15 to 20% of patients with aortic dissections. (53-56) The abrupt onset of chest pain with the sudden loss of pulse or blood flow to a lower extremity should raise a high suspicion of aortic dissection. The duplication of pulse is a rare physical finding in patients with aortic dissections and is probably due to the difference in flow rates in the true and false channels in cases in which a false lumen reenters the true lumen. (57) An examination of the neck may reveal unilateral vein distension resulting from obstruction secondary to the expanding false lumen around the aorta or from bilateral vein distension due to obstruction of the superior vena cava or from cardiac tamponade. Rare cases of right atrial compression, pulmonary artery obstruction, and aorto-right atrial fistula formation have been reported in the literature. (58-60)

Neurologic Involvement: Neurologic deficits have been associated with 18 to 30% cases of aortic dissection. (61,62) Cerebral isehemia/stroke is the most common neurologic manifestation associated with aortic dissection and has been reported to affect 5 to 10% of patients. (61-63) Most patients with aortic dissections who present with stroke also reveal a history of chest pain. Besides stroke, the altered cerebral perfusion may cause symptoms of transient cerebral hypoperfusion ranging from altered mental status to syncope, and among patients with proximal aortic dissection, up to 12% may present with syncope. (64) Spinal cord ischemia and ischemic peripheral neuropathies are more common with distal aortic dissections, and spinal cord involvement has been reported in up to 10% of these cases. (61) Spinal cord involvement in patients with aortic dissections could be secondary to the occlusion of the intercostal arteries, the artery of Adamldewicz, or the thoracic radicular arteries. A spinal cord watershed area found between the territories of the artery of Adamkiewicz and the thoracic radicular artery is more prone to ischemic damage from aortic dissection. (65) Spinal cord involvement in aortic dissection results in various spinal cord syndromes, including transverse myelitis, progressive myelopathy, spinal cord infarction, anterior spinal cord syndrome, paraplegia, and quadriplegia. (65-68)

The involvement of the peripheral nerves in cases of aortic dissection is due to neuronal ischemia or to the direct compression of a nerve by the false lumen. Although peripheral nerve involvement in patients with aortic dissection is rare, it may result in protean neurologic symptoms, including paresthesia in the limbs, hoarseness of voice, ischemic lumbosacral plexopathy, and Homer syndrome. (69-71) Most of the patients with aortic dissections who display the symptoms of neurologic involvement present with pain, but there are reports in the literature in which various neurologic symptoms, such as stroke, syncope, or hoarseness of voice, were the initial presenting features of the aortic dissection. (63-71)

Pulmonary Involvement: Pulmonary manifestations of aortic dissection are rare. The left pleural space is the most common space where the descending thoracic aortic dissection leaks. (72,73) Painless aortic dissection may be considered in the differential diagnosis of the unexplained, nontraumatic, left-sided hemorrhagic pleural effusion. Rare cases have been described in which the dissection eroded into or compressed the pulmonary artery or lung parenchyma, resulting in severe hemodynamic compromise, unilateral pulmonary edema, or hemoptysis. (74-76)

GI Involvement: Acute GI hemorrhage is a very rare presentation of the dissection of the descending aorta and has been limited to a few case reports. (77-79) Acute GI hemorrhage has resulted from erosion of the esophagus or duodenum. (77,78) Extension of the dissection into the mesenteric arteries has resulted in an acute abdomen. (80) Rarely, esophageal compression from the false lumen of aortic dissection has resulted in dysphagia. (81,82)

Clinical Prediction of Aortic Dissection

von Kodolitsch et al (52) devised a clinical prediction model for the initial prediction of aortic dissection based on history, physical findings, and chest radiography findings. In this study, 250 patients with acute chest pain, back pain, or both, and clinical suspicion of acute aortic dissection were examined for the presence of 26 clinical and radiographic variables by using multivariate analysis. The independent predictors of aortic dissection were identified as follows: chest pain with immediate onset, a tearing or ripping character, or both; pulse differentials, BP differentials, or both; and mediastinal widening, aortic widening, or both. The assessment of these three variables permitted the identification of 96% of acute aortic dissection cases. The probability of dissection was high (ie, [greater than or equalto] 83%) with isolated pulse or BP differentials, or any combination of the three variables, intermediate with isolated findings of aortic pain (31%) or mediastinal widening (39%), and probability was low (7%) with the absence of all three variables. This simple clinical model could be useful for a rapid assessment of the initial prediction of aortic dissection tailoring the prompt institution of confirmatory diagnostic imaging.

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of aortic dissection begins with clinical suspicion, which is the most crucial step in diagnosing this catastrophic disease. The next two important steps in the evaluation of patients with suspected aortic dissection are to confirm the presence of dissection and to differentiate between proximal and distal dissections. This information is critical, not only for deciding whether surgery is indicated, but also for deciding on the site for surgical access. The diagnosis should be confirmed rapidly and accurately, preferably with an easily available noninvasive modality. The planning for a therapeutic strategy depends not only on the type of dissection but also on the site of entry, the extent of dissection, the involvement of the coronary arteries, arch branches, or visceral arteries, the involvement of the aortic valve, the presence and extent of pericardial effusion, false lumen patency, and the presence of thrombus in the false lumen. Therefore, delineation of these features should be an important part of the diagnostic workup for patients with suspected aortic dissections. (83)

Chest radiography lacks the specificity for a diagnosis of aortic dissection. Similarly, ECG changes are nonspecific (chiefly, nonspecific ST-segment/T-wave changes), even though two thirds of patients with aortic dissections harbor these changes. CT scanning, MRI, and TEE are highly accurate techniques that are useful for the diagnosis of aortic dissection. Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) has limited diagnostic accuracy. Aortography is invasive, and serial studies are difficult due to the need of frequent femoral arterial punctures. Studies (reported later in this article) have demonstrated the existence of a serum biochemical marker (ie, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain marker) that is helpful in diagnosing aortic dissection.

Imaging Techniques

Aortic dissection may become fatal rapidly if left undiagnosed and untreated. Therefore, the choice of the initial imaging modality used to diagnose aortic dissection depends chiefly on the availability of a particular modality in the facility. The imaging modalities that are useful for the diagnosis of aortic dissection are CT scanning, MRI, TEE, and angiography. In various studies, each of these imaging techniques has been reported to have high sensitivity, specificity, diagnostic accuracy, and positive and negative predictive values. However, these values may vary significantly based on the prevalence of aortic dissection in the study population and are likely to be more applicable in the high-risk patients. Using Bayes theorem, Barbant et al (84) calculated the predictive values and accuracies of different imaging techniques for thoracic aortic dissection. In high-risk patients (ie, disease prevalence, 50%), the positive predictive values were > 85% for all four diagnostic modalities (ie, CT scanning, MRI, TEE, and aortography). However, for intermediate-risk patients (ie, disease prevalence, 10%), the positive predictive values were > 90% for CT scanning, MRI, and TEE but was 65% for aortography. In low-risk patients (ie, disease prevalence, 1%), the positive predictive values were < 50% for CT scanning, TEE, and aortography but was close to 100% for MRI. However, in all three types of patient populations, the negative predictive values and accuracies were > 85% for all four diagnostic modalities.

Chest Radiography: Although chest radiography lacks specificity for the diagnosis of aortic dissection, it could be of value for the initial prediction of the disease when used in combination with history and physical examination findings. The classic radiographic sign that is suggestive of aortic dissection is the widening of the mediastinal shadow, which has been reported in up to 50% of cases of aortic dissection. The mediastinum bulges to the right with dissection of the ascending aorta, and to the left with dissection of the descending thoracic aorta. (85,86) The other chest radiographic signs reported in patients with aortic dissection are altered configuration of the aorta, a localized hump on the aortic arch, a widening of the distal aortic knob past the origin of the left subclavian artery, aortic wall thickness indicated by the width of the aortic shadow beyond intimal calcification, displacement of the calcification in the aortic knob, a double aortic shadow, disparity in the sizes of the ascending and descending aortas, and the presence of a pleural effusion, most commonly on the left. (85,86) These radiographic signs are suggestive of, but not diagnostic of, aortic dissection.

CT Scanning: CT scanning was the most common initial diagnostic test that was performed in the patients enrolled in the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection, probably because it is less invasive and allows rapid diagnosis in emergency situations. (1,87) Sensitivities of 83 to 94% and specificities of 87 to 100% have been reported with the use of CT scanning for the diagnosis of aortic dissection except in cases of dissection of the ascending aorta, in which its sensitivity is < 80%. (88-91) The main disadvantages of the use of CT scanning, besides problems from the use of contrast material, are the following: difficulty in identifying the origin of the intimal tear; difficulty in assessing the involvement of aortic branch vessels; and inability to provide information about aortic valve regurgitation. (83)

Helical CT scanning is considered to be superior to conventional CT scanning for the detection of aortic dissection because in helical CT scanning more images are obtained during the peak levels of enhancement due to better tracking of the contrast material bolus. (92,93) Helical CT scanning also is associated with a higher rate of detection and better evaluation of lesions when there is respiratory motion along the patient's longitudinal axis. Furthermore, high-quality two-dimensional and three-dimensional reconstructions, which in turn are useful for the visualization of the course of the dissection membrane in the aortic arch relative to the origin of the subclavian artery, are possible with the use of helical CT scanning. (94,95) In distal dissections, this information is especially important to rule out the presence of retrograde dissection into the aortic arch, which may take place in 27% of cases of distal dissection and is associated with substantially higher mortality rates of up to 43%. Helical CT scanning is fast and easy to perform, and is probably the least operator-dependent imaging modality that is available for the detection of aortic dissection. It also allows better comparisons on follow-up studies, provided that the measurements are made in well-defined planes. However, the experience with the use of helical CT scanning is limited, and its role in the diagnosis of aortic dissection needs to be defined further.

MRI: Both the sensitivity and the specificity of MRI are in the range of 95 to 100%. (96-102) The MRI can detect aortic dissection accurately, can delineate the extent of the dissection, can demonstrate the site of the entry tear, can identify the arch vessels that are involved, and can assess the renal artery involvement. Spin echo ECG-gated sequences can help to identify slow flow within the false lumen. Cine and gradient recall echo sequences also provide useful dynamic information about the flow within the two lumens. Dynamic turbo flash-enhanced imaging can provide additional data when the results obtained with spin echo and cine sequences are inconclusive due to the presence of thrombus or lack of flow. (96) Mill is also well-suited for the evaluation of preexisting aortic disease, valvular involvement, and previous surgical repair. (97-102) In the studies that compared MRI with TEE or CT scanning, (97-102) the sensitivity and specificity of MRI was higher among the patients with previous aortic disease. In addition, the MRI has the capability to perform the three-dimensional reconstruction of the images in any plane.

The limitations of MRI include the lack of immediate availability, the delay from bedside to scanner, the long examination time, the limited access to the patient, and the restricted monitoring of vital signs, which is especially problematic in hemodynamically unstable patients, although the latter has improved since the advent of the short-bore MRI units. (103) Furthermore, it is not safe for patients with cardiac pacemakers, ferromagnetic aneurysm or hemostatic clips, and ocular or otologic implants to undergo MRI examinations. With the advent of MRI sequences such as the breath-hold gradient-echo and fast-gradient echo sequences, and segmental K-space acquisition, the procedure time can be reduced to < 5 min without compromising high accuracy.

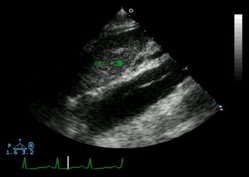

TTE: The sensitivity and specificity of TTE for the detection of aortic dissection range from 35 to 80% and 39 to 96%, respectively, depending on the anatomic location of the dissection. (104-107) On transthoracic M-mode echocardiography, floating intimal membranes, the enlargement of the aortic root, the enlargement of the aortic arch, and an increase in the aortic wall thickness were the initially described signs of aortic dissection. With the introduction of two-dimensional echocardiography and the feasibility of taking suprasternal, subcostal, and substernal views, it has become possible to directly visualize the ascending aorta and aortic arch for floating intimal membranes, intimal tears, and false lumens. However, despite these efforts, an analysis of the aorta by TTE remains difficult due to technical limitations, narrow intercostal spaces, obesity, and pulmonary emphysema. False-positive results have been observed in patients with dilated ascending aortas in whom artifacts from reverberations may appear like membranes. Although color flow Doppler studies could be of help in these cases, since no differential flow would be seen as expected in a false lumen in patients with aortic dissections, the TTE is by no means a conclusive test for ruling out the possibility of aortic dissection, even in the ascending aorta.

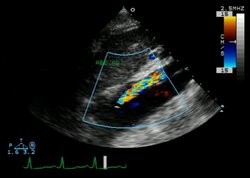

TEE: TEE is widely available, is safe in experienced hands, and can be performed quickly and easily at the bedside. These advantages make TEE ideal for use in most patients with aortic dissections, including relatively unstable patients. The sensitivity of TEE has been reported to be as high as 98%, and the specificity ranges from 63 to 96%. (108-116) Furthermore, TEE possesses the ability to identify the following: the entry site of dissection; the presence of thrombus in a false lumen; abnormal flow characteristics; the involvement of coronary and arch vessels; the presence, extent, and hemodynamic significance of pericardial effusion; and the presence and severity of aortic valve regurgitation. The most important diagnostic finding of aortic dissection that can be seen on TEEs is the presence of an undulating intimal flap within the aortic lumen that differentiates a false lumen from a true lumen. In order to avoid a false-positive diagnosis, the intimal flap has to be identified in more than one view, and it should have motion that is independent from that of the aortic wall. Furthermore, different color flow Doppler patterns should be visible in the two lumens. In cases in which the false lumen has undergone thrombosis, a central displacement of the intimal calcification and a thickening of the aortic wall may suggest the presence of aortic dissection. (117) The possibility of aortic dissection is increased if, in addition to the intimal flap, an entry site, color Doppler flow and/or thrombus in the false lumen, or aortic root dilation is seen.

The main limitations of TEE are its strong dependence on the investigator's experience and the difficulty in objectively documenting the pathologic findings for comparison with follow-up studies. The field of view is limited to the thoracic and proximal abdominal aorta, thus the distal extension of the dissection below the celiac trunk cannot be visualized by TEE. Furthermore, TEE cannot be performed in patients with esophageal varicosity or stenosis. (118) The study could also result in a false-negative finding due to the presence of an echocardiographic blind spot in the distal ascending aorta and proximal aortic arch secondary to the position of the air-filled trachea and left mainstem bronchus interposed between the esophagus and this part of the aorta. (110-112) False-positive results could occur as a result of reverberation echoes, fat-shift artifacts from the mediastinum, motion artifacts originating from the aneurysmal ascending aorta, calcified atheromatous plaque, and/or, in postoperative cases, periaortic hematoma. (119-122) A false-positive diagnosis not only mandates an urgent surgical intervention that requires full cardiopulmonary bypass and hypothermic circulatory arrest if arch involvement exists, but also deprives the patient of proper and timely treatment of the true disease. Supplementing TEE findings with additional imaging studies may improve diagnostic accuracy, especially in cases in which TEE findings are considered to be probable for the presence of aortic dissection and the clinical suspicion of aortic dissection is high. (122)

Aortography: Aortography has a sensitivity of 86 to 88% and a specificity of 75 to 94% for the diagnosis of thoracic aortic dissection. (123-126) It has long been considered the procedure of choice for the patients with suspected aortic dissection, but these days, because of being invasive and time-consuming, aortography rarely is used as the initial diagnostic procedure to detect aortic dissection. The aortographic findings seen in patients with aortic dissection include the splitting or distortion of the contrast column, flow reversal or stasis, altered flow pattern, the failure of major vessels to fill, and aortic valve insufficiency. Although coronary angiography in association with aortography may delineate coronary anatomy, especially when coronary artery involvement in a dissection is suspected, caution should be used in unstable patients for whom the coronary angiography may be dangerous due to the imposed delay of the surgical intervention.

Serum Smooth Muscle Myosin Heavy Chain

Interestingly, some studies (127-130) have demonstrated the existence of a serum biochemical marker of aortic dissection. Aortic dissection causes extensive damage to the smooth muscle cells of the media, leading to the release of structural proteins of the smooth muscle cells including smooth muscle myosin heavy chain into the circulation. An immunoassay to detect serum smooth muscle myosin heavy chain has been developed and is being tested as a potential tool that would be useful for the early detection of aortic dissection. (127-130) Serum levels of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain elevate significantly within the first 6 h after the onset of aortic dissection. (129-130) Cross-reactivity of the smooth muscle myosin heavy chain assay with the cardiac and skeletal muscle is < 0.05%, but the cross-reactivity against uterine myosin is 100%. The mean ([+ or -] SD) smooth muscle myosin heavy chain level in normal human sera taken from healthy individuals was 0.9 [+ or -] 0.4 [micro]g/L. (129) The clinical decision limit has been set at 2.5 [micro]g/L.

According to a report by Suzuki et al, (130) the serum values of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain were significantly higher in 95 patients with aortic dissection compared with 131 healthy volunteers (22.4 [+ or -] 40.4 [micro]/L vs 0.9 [+ or -] 0.4 [micro]g/L, respectively; p < 0.001). The highest levels (51.0 [+ or -] 52.3 [micro]g/L) were seen in 33 patients who presented within 3 h after the onset of symptoms. In 48 patients with acute myocardial infarctions, the mean serum levels of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain were 2.1 [+ or -] 1.6 [micro]g/L (p < 0.001 [compared with patients with aortic dissections]). The serum levels of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain were higher in patients with proxima] aortic dissections than in those with distal aortic dissections (p = 0.03), probably because the thoracic aorta has more smooth muscle than the abdominal aorta. In 33 patients with acute aortic dissections who presented within 3 h after the onset of symptoms, the sensitivity of the assay was 91% and the specificity of the assay was 98% compared with 131 healthy volunteers, and the specificity of aortic dissection was 83% compared with 48 patients who had acute myocardial infarctions. The diagnostic accuracy was 96%. The sensitivity of the assay decreased to 72% in next 3-h period and decreased to 30% thereafter. Serum levels of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain of > 10 [micro]/L showed 100% specificity for aortic dissection. The time taken to run the assay was 30 min.

Thus, the biochemical diagnosis of acute aortic dissection is rapid, can be established by a noninvasive test, and appears to be highly sensitive and specific. Once it is investigated further and becomes available on a commercial basis, it may become a useful initial step in triaging the patients with suspected aortic dissection, provided that patients present within 6 h, and preferably within 3 h, after the onset of symptoms. The assay also may help in judging the need for and urgency of performing additional diagnostic procedures.

Special Diagnostic Considerations

Differentiation of Aortic Dissection and Degenerative Aortic Disease: Aortic atherosclerosis is usually more obvious and the surface of the plaque is usually rough compared to the smooth delineation of the intimal flap. Mural thrombi are seen only in the dissection. However, it should be remembered that a rupture of aortic plaques could lead to aortic ulceration and dissection.

Differentiation of the True and False Lumens: Spontaneous echo contrast is usually visualized in a false lumen and is related to slow or delayed flow, (109,115,131) Compared to systolic forward flow in the true lumen, delayed or even reversed flow may be seen in the false lumen. However, the degree of color flow visualization in the false lumen is dependent on the extent of communication of the false lumen with the true lumen; when this communication is reduced or absent, color flow within the false lumen is reduced or absent as well. Moreover, the thrombus formation is only noted in the false lumen.

Localization of Intimal Tears: Intimal tears can be visualized directly by both MRI and TEE. (108,114) Usually, patients have both entry and reentry tears and, in addition, may have multiple intermediary tears. (115) Flow across the tear is often bidirectional, and variable flow patterns can be seen during a long diastole. The pressure gradient at the entry tear is rarely of substantial magnitude since the pressure in the false lumen is systemic.

Communicating and Noncommunicating Dissection: Noncommunicating dissections are rare (ie, < 10% of cases). They can be differentiated from communicating dissections by visualizing the flow in the false lumen and by detecting both the entry and exit tears in the intimal flap. (115,131) The filling of the false lumen with thrombus is found more often in patients with noncommunicating dissections. Therefore, differentiation between the intramural hematoma and a small noncommunicating dissection sometimes may be difficult to establish. (131)

Aortic Regurgitation: Since aortic regurgitation is present in up to 50% of patients with proximal aortic dissection, the determination of the degree of severity and the pathophysiologic mechanisms involved in the causation of the regurgitation is important for the planning of the surgical intervention in these cases. (132) Both TTE and TEE can provide valuable information in this regard. Color Doppler studies have high sensitivity and specificity for the visualization and semiquantitative analysis of aortic regurgitation. (133)

Side Branch Involvement: Myocardial ischemia and infarctions that are related to aortic dissection contribute significantly in the perioperative mortality of aortic dissections. (134) The development of a new regional wall motion abnormality in the left ventricle could be a sign of involvement of a coronary artery in the dissection process. Direct evidence of coronary involvement may be present during TEE with the intimal flaps seen in the ostium of the right or left coronary arteries. In unstable patients with aortic dissections for whom coronary angiography may be dangerous due to the imposed delay of surgical intervention, these echocardiographic findings may be especially helpful. (135,136) Knowledge of the involvement of the aortic arch vessels, renal arteries, and iliofemoral arteries is important for surgical planning. MRI and vascular sonography with duplex scanning are two useful techniques for studying these vessels.

Blood Extravasation: The extravasation of blood in the pericardium, pleural space, or mediastinum often signals an emergency because of the high likelihood of the penetration or rupture of the dissection into these spaces. (115,131) Eehocardiography, CT scanning, and MRI are all highly accurate in identifying blood accumulation in the pericardium, pleural space, or mediastinum. The compression of cardiac chambers by mediastinal hematoma also can be detected accurately by all three of these techniques. The TTE is the procedure of choice to rule out cardiac tamponade. Extravasation of blood into the pleural space also can be diagnosed by chest radiography.

Intramural Hemorrhage and Hematoma: The diagnostic features of intramural hemorrhage are the presence of multiple layers of the aortic wall with splitting due to hemorrhage and increasing wall thickness (ie, > 0.5 cm), as manifested by an increase in the distance from the aortic lumen to the esophagus. (137) Both TEE and MRI can detect intramural hemorrhage and hematoma accurately. The diagnostic features of intramural hematoma on TEE include the following: localized thickening of the aortic wall; intramural echo-free spaces; the absence of the dissection membrane, communication or Doppler flow signal; and the central displacement of intimal calcification. (137-139) MRI has a unique capability not only of diagnosing intramural hematoma, but also of detecting serial pathologic changes taking place within the hematoma, which may be helpful in identifying the progression or regression of a hematoma on follow-up studies. MRI also possesses the ability to assess the age of the hematoma based on the formation of methemoglobin. (14) High-intensity signals on both T1-weighted and T2-weighted images produced by methemoglobin indicate the subacute nature of the intramural hematoma, whereas recent bleeding results in signals of different intensities within various regions of the hematoma. (33-35)

Atherosclerotic Aortic Ulcer: CT scanning was the initial imaging study established as an accurate modality for imaging penetrating atherosclerotic aortic ulcers. However, such imaging requires the optimal contrast filling of the aortic lumen and ulcer crater. (25,141) MRI has shown higher accuracy to detect penetrating atherosclerotic aortic ulcers when compared with contrast-enhanced CT scanning and could be of particular value when contrast injection is contraindicated. (23,142) Although the utility of TEE for the diagnosis of penetrating atherosclerotic aortic ulcers has been well-documented, the ulcers present at the level of the echocardiographic blind spot in the distal ascending aorta and the proximal part of the aortic arch could be missed on TEE. (24,119,143)

Follow-up Studies: About 15% of patients with aortic dissections who are treated surgically require a second operation because of the progression of an existing dissection, the development of a new dissection, or the formation of an aortic aneurysm. New dissections may develop at the anastomosis sites or at the aortic parts not involved before. Both TEE and MRI allow imaging of the Dacron prosthesis and anastomosis sites as well as of the other parts of the aorta that were not involved previously. (115,131) Similarly, both procedures can detect aortic dilatation and aneurysm formation on follow-up studies.

TREATMENT

Medical Treatment

IV antihypertensive treatment should be started emergently in all patients, except in those with hypotension, as soon as the diagnosis of acute aortic dissection is suspected. The aims of the medical therapy are to reduce the force of the left ventricular contractions, to decrease the steepness of the rise of the aortic pulse wave (ie, dP/dt), and to reduce the systemic arterial pressure to as low a level as possible without compromising perfusion to the vital organs. In the experimental models of dissection, laminar nonpulsatile flow is associated with the cessation of the advancement of dissection, whereas pulsatile flow of increasing acceleration results in the continuation of dissection in both directions from the initial intimal tear. Therefore, reducing the rate of rise of the aortic pulse by decreasing the force of the left ventricular contractions would retard the propagation of the dissection and decrease the risk of aortic rupture.

Historically, in the early 1960s, Wheat et al (144) introduced drug therapy for aortic dissection by originally using reserpine and guanethidine. At the present time, a combination of a [beta]-blocker and a vasodilator (ie, sodium nitroprusside) is a standard medical therapy used in patients with aortic dissections. [beta]-blocker therapy should be instituted before starting sodium nitroprusside therapy. Otherwise, the reflex catecholamine release secondary to the direct vasodilatation caused by sodium nitroprusside may result in an increase in the left ventricular contraction force and aortic pulse dP/dt, resulting in propagation of the dissection. (19) Labetalol, an [alpha]-adrenergic and [beta]-adrenergic antagonist, is an alternative to the combination of a [beta]-blocker and sodium nitroprusside. (145) Trimethaphan, a ganglionic blocker as well as a direct vasodilator, can be used when the above-mentioned agents are ineffective, poorly tolerated, or contraindicated. Trimethaphan would serve to decrease both the aortic pulse dP/dt and the systemic BP. However, the efficacy of trimethaphan is less predictable than that of sodium nitroprusside, and it may cause tachyphylaxis, severe hypotension, urinary retention, and ileus.

Patients with uncomplicated distal aortic dissections can be managed medically in the acute phase, as the survival rate is around 75% whether patients are treated medically or surgically. (146) Furthermore, patients with distal dissections are usually older and often are experiencing concomitant cardiac, pulmonary, and/or renal diseases. Also, those patients with proximal dissections who have significant comorbid diseases that preclude urgent surgery ought to be treated medically. The goals of medical treatment in patients with acute aortic dissections are to stabilize the dissection, prevent rupture, accelerate healing, and reduce the risk of complications. (147)

The potential problems encountered during medical treatment could be the extension of the dissection, expansion of the aneurysm, and compression of the adjacent structures, resulting in organ malperfusion. The clinical picture of these patients includes recurrent episodes of pain, abdominal distension, increasing metabolic acidosis, progressive elevation of liver enzymes, and/or worsening of renal function. Serious consideration should be given to performing surgery in these patients. The main causes of death in patients being treated medically are aortic rupture and organ malperfusion.

Surgical Treatment

Surgical intervention is indicated in all patients with proximal dissections, with the exception of patients with serious concomitant conditions that preclude surgery. (148) Stroke is often a contraindication to surgery because there is real concern that anticoagulation therapy and reperfusion can result in further neurologic deterioration by converting the ischemic stroke to a hemorrhagic stroke. A careful assessment for the presence of aortic regurgitation and pericardial effusion, the extension of the dissection into the major aortic branches, the localization of entry and reentry sites, and the presence of thrombosis in the false lumen yields information that can be helpful in planning the approach to and the extent of surgery. (149) The indications for performing early surgery in patients with distal dissections are the rapid expansion of a dissecting aneurysm, blood leakage, impending rupture, persistent and uncontrollable pain, and/or impairment of the blood flow to an organ or limb. (150-153) The operative mortality rate for patients with aortic dissections ranges from 5 to 10% and may approach 70% in cases with complications. The independent predictors of operative mortality include the presence of cardiac tamponade, the site of the tear, the time to operation, the presence of renal/visceral ischemia, renal dysfunction, and the presence of pulmonary disease. (154) The best technique for the surgical treatment of aortic dissection has yet to be determined. The best-known procedures for complete replacement of the ascending aorta are the Bentall, the Cabrol, the button, and the elephant trunk techniques. (8) The selection of a particular surgical technique has to be determined by each surgeon in the light of his own experience. Most of the surgical procedures are combined with glue aortoplasty. (155) The aim of surgical treatment is to excise and replace the aortic segment containing the origin of the dissection, not to replace the entire dissected aorta. In about 50% of patients who are treated surgically, a part of the aortic dissection persists.

Glue aortoplasty is an important contribution to modern-day aortic dissection surgery. Tissue adhesives are used to conjoin the dissected aortic wall layers and to aid the performance of blood-tight anastomosis on the aorta. The first tissue adhesive, which was used in the 1970s, was gelatin-resorcin-formalin glue. (156) With the use of glues, a complete disappearance of the false lumen has been achieved in > 50% of the patients. (157,158) The use of tissue glue has been reported to significantly reduce the number of aortic valve replacements, the amount of intraoperative and postoperative bleeding, the volume of intraoperative blood transfusions, and the frequency and severity of postoperative complications. (159-161) Although better long-term postoperative survival rates have been reported since the start of the use of glue aortoplasty in the 1970s, no controlled studies have directly compared the effect of glue aortoplasty on long-term postoperative survival. (159-161)

Treatment With Endovascular Stent Placement

Interest has grown in treating patients with aortic dissections with endovascular stent placement. So far, studies on this technique have been conducted in a small number of high-risk surgical patients, mostly with descending aortic dissections who displayed symptoms of abdominal organ malperfusion (ie, bowel, liver, and/or kidney) or lower extremity malperfusion. (162-168) The stents have been placed in the true lumen or the false lumen and have been combined with balloon fenestration of the intimal flaps in some cases. (162,163,167) Organ malperfusion and ischemia in patients with aortic dissections are caused by encroachment on the aortic lumen that provides the blood supply to a branch vessel. The lumen supplying blood to the branch vessel may be the true lumen or the false lumen. A stent is deployed through the percutaneous approach within the lumen supplying the branch vessel to hold the lumen open by displacing the intimal flap toward and overcoming the pressure from the other lumen. To overcome the high pressures in the other lumen, a balloon fenestration procedure may be combined with the stent procedure. The fenestration alone has been used to equalize the pressure between false and true lumens to relieve the compression exerted by the high-pressure lumen on the surrounding structures. A potential risk of fenestration is in allowing distal embolization in the setting of partial thrombosis of the lumen.

The clinical success of endovascular stent placement for aortic dissection ranges from 76 to 100% with a reported 30-day mortality rate of up to 25%. (162-167) Data on the long-term follow-up of these patients are scarce. According to a report by Slonim et al (162) on 40 patients with aortic dissections (distal dissection, 30 patients; proximal dissection, 10 patients) who were treated with endovascular stent placement, 10 patients died during the first month and 5 more patients died during a subsequent mean follow-up period of 29 months. The procedure-related complications reported with aortic endovascular stent placement include bowel infarction, renal failure, lower extremity embolism, false lumen rupture, and postimplantation syndrome (ie, transient elevation of body temperature and C-reactive protein level, and mild leukocytosis), with the reported incidence of these complications ranging from 0 to 75%. (162-168)

While the exact definition of the aortic dissection patients who will potentially benefit from endovascular stent placement needs to be determined, at this time the procedure could be considered as a palliative measure for symptomatic patients with distal aortic dissections whose symptoms are secondary to organ or lower extremity malperfusion. The fenestration/stent treatment could be used in those patients with proximal dissections who are unstable for surgery that could be performed later once they become stable. Although smaller studies have reported early success with endovascular stent placement and a trend for lower mortality rates, the true assessment of the effectiveness and safety of this procedure await the conducting of large-scale studies with long-term follow-up. At present, about 13% of patients with aortic dissections receive stentgraft treatment, and this proportion is steadily increasing. With more data available and more advancement in operator expertise, stent graft placement may, in the future, become the standard treatment for most cases of distal aortic dissection, because waiting for the complications to occur may not be prudent since the operative mortality rate in these situations approaches 70%. (154)

Treatment of Aortic Intramural Hematoma and Atherosclerotic Aortic Ulcer

The treatment of patients with both aortic intramural hematomas and atherosclerotic aortic ulcers is similar to that for patients with classic aortic dissections and, likewise, depends on the aortic site involved. Both aortic intramural hematoma and atherosclerotic aortic ulcer are far more common in the descending aorta and, therefore, are treated with aggressive medical therapy. Medical therapy should consist of the optimal control of BP, a decrease in aortic pulse dP/dt, and the control of risk factors for atherosclerosis, as well as close long-term follow-up. Surgery is preferred for the treatment of patients with intramural hematomas and atherosclerotic aortic ulcers in the ascending aorta and aortic arch, and of patients with progressive dilatation and aneurysm formation of the aorta, irrespective of the site of involvement. (32-36) In a meta-analysis of 143 patients with aortic intramural hematomas, of whom 30 patients (21%) died, 20 deaths (67%) were due to aortic dissection or rupture. (169)

Long-term Treatment and Follow-up

Although the dissection of the aorta is an acute event, in most cases an underlying chronic and generalized disease of the media of the aortic wall predispose the aorta to dissection, and this underlying pathology persists even in those cases in which the surgical repair is radical. The potential for aneurysm formation, progressive dissection, and redissection of the remainder of the aorta demands careful monitoring of long-term survivors. (170-172) The long-term management of the survivors of aortic dissection consists of aggressive medical management and a close follow-up with clinical and imaging assessment of the aorta to detect potential complications, which could be corrected at the initial stages with reoperations. An enlarging saccular aneurysm portends an impending aortic rupture and should be repaired promptly. On long-term follow-up, saccular aneurysms have been reported (173) to develop in as many as 14 to 29% of patients with distal dissections. The long-term medical management consists of optimal BP control and long-term therapy with [beta]-blockers, even in patients with no history of hypertension. Patients with the hypertensive etiology of dissection have a better long-term survival rate and are at lower risk of developing dissection-related long-term complications. A good control of BP may reduce the incidence of redissection to about one third of patients (ie, 45 to 17%). (10)

PROGNOSIS

Despite improved diagnostic and therapeutic techniques, the overall in-hospital mortality rate of patients with aortic dissections (ie, approximately 30% for patients with proximal dissections and approximately 10% for those with distal dissections) has not decreased in the last 3 decades. (174,175) The predictors of in-hospital mortality include proximal dissection, age > 65 years, migrating characteristic of the pain, shock, pulse deficits, and the presence of neurologic deficits. The long-term survival rates of patients with proximal aortic dissections who undergo surgical repair and survive long enough to leave the hospital are 65 to 80% at 5 years and 40 to 50% at 10 years. (147,174,176) Information on the long-term prognosis of patients distal aortic dissections who have been operated on and of those who have not been operated on is limited. (176,177) The long-term prognosis may vary within the group of patients with distal aortic dissections, and outcome appears to be particularly worse for patients with retrograde arch and ascending aortic involvement and in those with patent false lumens that are absent of thrombosis. (147,150,177) The most common cause of death in long-term survivors of aortic dissections is the rupture of the aorta due to a subsequent dissection or aneurysm formation. The prognosis for patients with aortic intramural hematomas is similar to that for patients with classic aortic dissections. (178)

REFERENCES

(1) Hagan PG, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, et al. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): new insights into an old disease. JAMA 2000; 283:897-903

(2) Spittell PC, Spittell JA Jr, Joyce JW, et al. Clinical features and differential diagnosis of aortic dissection: experience with 236 cases (1980 through 1990). Mayo Clin Proc 1993; 68:642-651

(3) Bickerstaff LK, Pairolero PC, Hollier LH, et al. Thoracic aortic aneurysms: a population-based study. Surgery 1982; 92:1103-1108

(4) Eisenberg MJ, Rice SA, Paraschos A, et al. The clinical spectrum of patients with aneurysms of the ascending aorta. Am Heart J 1993; 125:1380-1385

(5) DeBakey ME, Henly WS, Cooley DA, et al. Surgical management of dissecting aneurysms of the aorta. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1965; 49:130-148

(6) Dailey PO, Trueblood HW, Stinson EB, et al. Management of acute aortic dissections. Ann Thorac Surg 1970; 10:237-246

(7) Wilson SK, Hutchins GM. Aortic dissecting aneurysms: causative factors in 204 subjects. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1982; 106:175-180

(8) Auer J, Berent R, Eber B. Aortic dissection: incidence, natural history and impact of surgery. J Clin Basic Cardiol 2000; 3:151-154

(9) Hirst AE Jr, Johns VJ Jr, Kime SW Jr. Dissecting aneurysms of the aorta: a review of 505 cases. Medicine 1958; 37:217-279

(10) DeBakey ME, McCallum CH, Crawford ES, et al. Dissection and dissecting aneurysms of the aorta: twenty-year follow up of five hundred twenty-seven patients treated surgically. Surgery 1982; 92:1118-1134

(11) Hennessy TG, Smith D, McCann HA, et al. Thoracic aortic dissection or aneurysm: clinical presentation, diagnostic imaging and initial management in a tertiary referral center. Ir J Med Sci 1996; 165:259-262

(12) Fox R, Ren JF, Panidis IP, et al. Anuloaortic ectasia: a clinical and echocardiographic study. Am J Cardiol 1984; 54:177-181

(13) Litchford B, Okies JE, Sugimura S, et al. Acute aortic dissection from cross-clamp injury. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1976; 72:709-713

(14) Archer AG, Choyke PL, Zeman RK, et al. Aortic dissection following coronary artery bypass surgery: diagnosis by CT. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1986:142-145

(15) Coady MA, Rizzo JA, Elefteriades JA. Pathologic variants of thoracic aortic dissections: penetrating atherosclerotic ulcers and intramural hematomas. Cardiol Clin 1999; 17:637-657

(16) Perron AD, Gibbs M. Thoracic aortic dissection secondary to crack cocaine ingestion. Am J Emerg Med 1997; 15:507-509

(17) Fisher A, Holroyd BR. Cocaine-associated dissection of the thoracic aorta, j Emerg Med 1992; 10:723-727

(18) Eber B, Tscheliessnigg KH, Anelli-Monti M, et al. Aortic dissection due to discontinuation of beta-blocker therapy. Cardiology 1993; 83:128-131

(19) Wheat MW. Acute dissection of the aorta. Cardiovasc Clin 1987; 17:241-262

(20) O'Gara PT, DeSanctis RW. Acute aortic dissection and its variants: toward a common diagnostic and therapeutic approach. Circulation 1995; 92:1376-1378

(21) Bluemke DA. Definitive diagnosis of intramural hematoma of the thoracic aorta with MR imaging. Radiology 1997; 204:319-321

(22) Stanson AW, Kazmier FJ, Hollier LH, et al. Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcers of the thoracic aorta: natural history of clinicopathologic correlations. Ann Vasc Surg 1986; 1:15-23

(23) Yucel EK, Steinberg FI, Egglin TK, et al. Penetrating aortic ulcers: diagnosis with MR imaging. Radiology 1990; 177: 779-781

(24) Vilacosta I, San Roman J, Aragoncillo P, et al. Penetrating atherosclerotic aortic ulcer: documentation by transesophageal echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998; 32:83-89

(25) Kazerooni EA, Bree RL, Williams DM. Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcers of the descending thoracic aorta: evaluation with CT and distinction from aortic dissection. Radiology 1992; 183:759-765

(26) Harris JA, Bis KG, Glover JL, et al. Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcers of the aorta. J Vasc Surg 1994; 19:90-98

(27) Cooke JP, Kazmier FJ, Orszulak TA. The penetrating aortic ulcer: pathologic manifestations, diagnosis, and management. Mayo Clin Proc 1988; 63:718-725

(28) Meszaros I, Morocz J, Szlavi J, et al. Epidemiology and clinicopathology of aortic dissection. Chest 2000; 117:1271-1278

(29) Pitt MP, Bonser RS. The natural history of thoracic aortic aneurysm disease: an overview. J Card Surg 1997; 12(suppl): 270-278

(30) Anagnostopoulos CE, Prabhar MJS, Kittle CF. Aortic dissection and dissecting aneurysms. Am J Cardiol 1972; 30:263-273

(31) Veyssier-Belot C, Cohen A, Rougemont D, et al. Cerebral infarction due to painless thoracic aorta and common carotid artery dissection. Stroke 1993; 24:2111-2113

(32) Robbins RC, McManus RP, Mitchell RS, et al. Management of patients with intramural hematoma of the thoracic aorta. Circulation 1993; 88:II1-II10

(33) Nienaber CA, von Kodolitsch Y, Petersen B, et al. Intramural hemorrhage of the thoracic aorta: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Circulation 1995; 92:1465-1472

(34) Muluk SC, Kaufman JA, Torchiana DF, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of thoracic aortic intramural hematoma. J Vasc Surg 1996; 24:1022-1029

(35) Murray JG, Manisali M, Flamm SD, et al. Intramural hematoma of the thoracic aorta: MR image findings and their prognostic implications. Radiology 1997; 204:349-355

(36) Harris KM, Braverman AC, Gutierrez FR, et al. Transesophageal echocardiographic and clinical features of aortic intramural hematoma. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1997; 114: 619-626

(37) Zotz R, Erbel R, Meyer J. Intrawall hematoma of the aorta as an early sign of aortic dissection. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1991; 4:636-638

(38) Song JK, Kim HS, Kang DH, et al. Different clinical features of aortic intramural hematoma versus dissection involving the ascending aorta. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001; 37:1604-1610

(39) Hussain S, Glover JL, Bree R, et al. Penetrating atherosclerotic ulcers of the thoracic aorta. J Vasc Surg 1989; 9:710-717

(40) Tisnado J, Cho SR, Beachley MC, et al. Ulcerlike projections: a precursor angiographic sign to thoracic aortic dissection. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1980; 135:719-722

(41) Sullivan PR, Wolfson AB, Leckey RD, et al. Diagnosis of acute thoracic aortic dissection in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med 2000; 18:46-50

(42) Khan IA, Vasavada BC, Sacchi TJ. Asymptomatic dissection of the ascending aorta: diagnosis by transesophageal echocardiography. Am J Emerg Med 1999; 17:172-173

(43) Khurana B, Goorahoo P, Friedman SA. Silent aortic dissection with hemopericardium: diagnosis by computerized tomography. Chest 1988; 93:652-653

(44) Friese KK, Steffens JC, Caputo GR, et al. Evaluation of painless aortic dissection with MR imaging. Am Heart J 1991; 122:1169-1173

(45) Khan IA. Clinical manifestations of aortic dissection. J Clin Basic Cardiol 2001; 4:265-267

(46) Rahmatullah SI, Khan IA, Caccavo ND, et al. Painless limited dissection of the ascending aorta presenting with aortic valve regurgitation. Am J Emerg Med 1999; 17:700-701

(47) Garcia-Jimenez A, Peraza-Torres A, Martinez-Lopez G, et al. Cardiac tamponade by aortic dissection in a hospital without cardiothoracic surgery. Chest 1993; 104:290-291

(48) Patel YD. Rupture of an aortic dissection into the pericardium. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1986; 9:222-224

(49) Armstrong WF, Bach DS, Carey L, et al. Spectrum of acute aortic dissection of the ascending aorta: a transesophageal echocardiographic study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1996; 9:646-656

(50) Carittenden MD, Maitland A, Canepa-Ansen R, et al. Aorta-right atrial fistula: an unusual complication of ascending aortic dissection. Can J Surg 1987; 30S:380-381

(51) Maor N, Lorber A, Weiss D. Atrioventricular block complicating dissecting aneurysm of the aorta. Int J Cardiol 1987; 15:352-354

(52) von Kodolitsch Y, Schwartz AG, Nienaber CA. Clinical prediction of acute aortic dissection. Arch Intern Med 2000; 160:2977-2982

(53) Fann JI, Sarris GE, Mitchell RS, et al. Treatment of patients with aortic dissection presenting with peripheral vascular complications. Ann Surg 1990; 212:705-713

(54) Schoon IM, Holm J, Sudow G. Lower-extremity ischemia in aortic dissection: report of three cases. Scand Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1985; 19:93-95

(55) White TJ III, Pinstein ML, Scott RL, et al. Aortic dissection manifested as leg ischemia. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1980; 135:353-356

(56) Salzberg MR, Kramer RJ. Dissecting thoracic aortic aneurysm in a 16-year-old. Ann Emerg Med 1984; 13:191-193

(57) Nissim JA. Dissecting aneurysm of aorta: a new sign. Br Heart J 1946; 8:203-206

(58) Link MS, Pietrzak MP. Aortic dissection presenting as superior vena cava syndrome. Am J Emerg Med 1994; 12:326-328

(59) Rau AN, Glass MN, Waller BF, et al. Right pulmonary artery occlusion secondary to a dissecting aortic aneurysm. Clin Cardiol 1995; 18:178-180

(60) Schofield PM, Bray CL, Brooks N. Dissecting aneurysm of the thoracic aorta presenting as right atrial obstruction. Br Heart J 1986; 55:302-304

(61) Alverez Sabin J, Vazquez J, Sala A, et al. Neurologic manifestations of dissecting aneurysm of the aorta. Med Clin (Barc) 1989; 92:447-449

(62) Prendes JL. Neurovascular syndromes in aortic dissection. Am Fam Physician 1981; 23:175-179

(63) Gerber O, Heyer EJ, Vieux U. Painless dissections of the aorta presenting as acute neurologic syndromes. Stroke 1986; 17:644-647

(64) Kuhlmann TP, Powers RP. Painless aortic dissection: an unusual cause of syncope. Ann Emerg Med 1984; 13:549-551

(65) Holloway SF, Fayad PB, Kalb RG, et al. Painless aortic dissection presenting as a myelopathy. J Neurol Sci 1993; 120:141-144

(66) Beach C, Manthey D. Painless acute aortic dissection presenting as left lower extremity numbness. Am J Emerg Med 1998; 16:49-51

(67) Rosen SA. Painless aortic dissection presenting as spinal cord ischemia ischemia. Ann Emerg Med 1988; 17:840-842

(68) Krishnamurthy P, Chandrasekaran K, Rodriguez Vega JR, et al. Acute thoracic aortic occlusion resulting from complex aortic dissection and presenting as paraplegia. J Thorac Imaging 1994; 9:101-104

(69) Greenwood WR, Robinson MD. Painless dissection of the thoracic aorta. Am J Emerg Med 1986; 4:330-333

(70) Lefebvre V, Leduc JJ, Choteau PH. Painless ischemic lumbosacral plexopathy and aortic dissection [letter]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1995; 58:641

(71) Khan IA, Wattanasauwan N, Ansari AW. Painless aortic dissection presenting as hoarseness of voice: cardiovocal syndrome; Ortner's syndrome. Am J Emerg Med 1999; 17:361-363

(72) Gendelman G, Barzilay N, Krupsky M, et al. Left pleural hemorrhagic effusion: a presenting sign of thoracic aortic dissecting aneurysm. Chest 1994; 106:636-638

(73) Little S, Johnson J, Moon BY, et al. Painless left pleural hemorrhagic effusion: an unusual presentation of dissecting ascending aortic aneurysm. Chest 1999; 116:1478-1480

(74) Massetti M, Babatasi G, Saloux E, et al. Aorto-pulmonary fistula: a rare event in the evolution of a dissecting aneurysm of the thoracic aorta. Eur J Cardiovasc Surg 1997; 11:994-996

(75) Takahashi M, Ikeda U, Shimada K, et al. Unilateral pulmonary edema related to pulmonary artery compression resulting from acute dissecting aortic aneurysm. Am Heart J 1993; 126:1225-1227

(76) Guidetti AS, Pik A, Peer A, et al. Haemoptysis as the sole presenting symptom of dissection of the aorta. Thorax 1989; 44:444-445

(77) Nath HP, Jaques PF, Soto B, et al. Aortic dissection masquerading as gastrointestinal disease. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1986; 9:37-41

(78) Roth JA, Parekh MA. Dissecting aneurysms perforating the esophagus [letter]. N Engl J Med 1978; 299:776

(79) O'Dell KB, Hakim SN. Dissecting thoracic aortic aneurysm in a 22-year-old man. Ann Emerg Med 1990; 19:316-318

(80) Edwards KC, Katzen BT. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome due to a large dissecting abdominal aortic aneurysm. Am J Gastroenterol 1984; 79:72-74

(81) Elloway RS, Mezwa DG, Alexander T. Foregut ischemia and odynophagia in a patient with a type III aortic dissection. Am J Gastroenterol 1992; 87:790-793

(82) Svensson LG, Shahian DM, Davis FG, et al. Replacement of entire aorta from aortic valve to bifurcation during one operation. Ann Thorac Surg 1994; 58:1164-1166