A 64-year-old white woman with a past medical history of osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, hyperthyroidism, and hypercholesterolemia presented with chest and neck pain, headache, blurring of vision, and numbness of the right lower extremity for a few hours. She was found to have a pulse rate of 60 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute, and blood pressure of 98 mm Hg, palpable. Heart and lung sounds were unremarkable. Her right leg was pale, cold, and numb with decreased touch and pain sensation. Her laboratory data showed a creatine kinase level of 414 U/L (reference range, 260-140 U/L), creatine kinase MB fraction of 17.5 U/L (reference range, 0-13.9 U/L), and troponin level less than 0.01 × 10^sup -6^ mg/ mL. Electrocardiogram revealed sinus rhythm at 60 beats per minute and left bundle branch block. Chest radiography showed normal lung fields without mediastinal widening. Doppler study of the lower extremities found no flow in the right leg and normal flow in the left leg. Head computed tomography was negative for hemorrhage or tumor. Her condition progressively deteriorated, and the patient died 1 day after admission. A complete autopsy was performed.

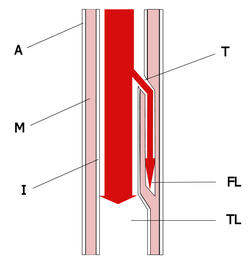

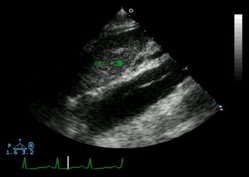

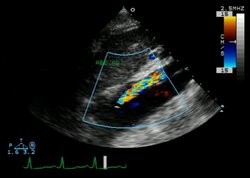

The pericardial sac was found to be distended with the formation of hemopericardium (400 mL of blood and blood clots). The ascending aorta was enlarged and distended (Figure 1). The outer surface was smooth, glistening, and dark brown. On opening, the aorta showed dissection involving ascending and descending portions (Figure 1, inset; Figure 2). The false lumen between the intima and adventitia was filled with a large amount of blood and blood clots (Figure 1, inset; Figure 3). There was a tear in the intima in the right lateral wall of the ascending aorta where usually the greatest shear force on the artery wall results from blood expelled from the heart under high pressure. The entry of blood between the intima and adventitia extended forward and all the way down the descending aorta, terminating just at the junction between the descending aorta and the iliac artery (Figure 2). The dissection also extended proximally toward the heart. Passage of blood into the pericardial cavity was retrograde through a small channel communicating with the false lumen. Acute onset of hemopericardium resulted in cardiac tamponade, which was the main cause of death for this patient. Microscopically, the dissecting hematoma spread along the laminar planes of the media between the middle and outer thirds, and elastic staining of an aortic wall specimen did not demonstrate cystic medial degeneration (Figure 3). Other significant findings included hemorrhage in the mediastinum and the right ureter, left ventricular hypertrophy, and mild atherosclerosis of the left circumflex, right coronary, and basal arteries.

In elderly patients, hypertension is the most common cause of aortic dissection.1 However, this patient had no previous history of hypertension and clinically manifested with hypotension rather than hypertension. Recent clinical investigations of 274 cases demonstrated that 49% of patients with aortic dissection have elevated blood pressure, 31% have pulse deficits, and 17% have focal neurological deficits. The presence of pulse deficits or focal neurological deficits increases the likelihood of an acute aortic dissection.2 Systemic or localized abnormalities of connective tissue that affect the aorta, such as Marfan syndrome, should be investigated. The most frequent preexisting, histologically detectable lesion is cystic medial degeneration, which consists of elastic tissue fragmentation and separation of the elastic and fibromuscular elements of the tunica media by small cystic spaces filled with amorphous extracellular matrix.1 The elastic stain is advantageous for the detection of cystic medial degeneration.

References

1. Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T. Robbins Pathologic Basis of Disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1999:526-529.

2. Klompas M. Does this patient have an acute thoracic aortic dissection? JAMA. 2002;287:2262-2271.

Linjun Xie, MD; Henry J. Shih, MD; Lester Freedman, MD

Accepted for publication January 7, 2004.

From the Department of Pathology, Nassau University Medical Center, East Meadow, NY.

The authors have no relevant financial interest in the products or companies described in this article.

Reprints: Linjun Xie, MD, Department of Pathology, Box 47, Nassau University Medical Center, 2201 Hempstead Turnpike, East Meadow, NY 11554 (e-mail: lxie555@hotmail.com).

Copyright College of American Pathologists May 2004

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved