In 1989, Ken Duckworth, M.D., had just started his fellowship in child psychiatry at the Massachusetts Mental Health Center in Boston when he was diagnosed with an early stage of testicular cancer.

"I felt a lump and 'pow!' My life changed in a short period of time," recalled Dr. Duckworth, who is now medical director of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill in Arlington, Va.

He endured surgery and a year of chemotherapy. "I didn't have the easiest type of [cancer], but thanks to the miracles of technology I was able to have three children with my wife and I'm still alive, so I feel very blessed that I was fortunate enough to pick a cancer that was curable," he said.

After his treatment and surgery, Dr. Duckworth saw his physician for routine scans and follow-up visits, but it took about 5 years for the shock of the initial diagnosis to subside. "I felt like I was looking over my shoulder a lot. I started to relax a little bit, but I don't think a day goes by that it's not in my consciousness. In that way, the old expression 'Anything that doesn't kill you makes you stronger' is kind of true."

Despite the misfortune, he managed to complete his child psychiatry fellowship on time, thanks to support from his family and colleagues. "They made allowances for me to get the chemotherapy I needed," he said. "It was nice to see people stepping up to look after me."

The incident caused him to evaluate his priorities and embrace healthy living as a way of life. For example, he tries to eat 10 fruits and vegetables a day (including piling on six slices of tomato when he has a hamburger); he swims twice a week, plays basketball, and caps his work week at 40 hours so he can spend time with his family.

His experience as a patient with a serious illness made him realize the importance of actively pursuing treatment options. "You get no extra points for being a doctor. You're a man getting chemotherapy," he said. "Get second opinions. Don't be a passive recipient of medical advice, because I got very conflicting medical advice."

One physician took a wait-and-see approach. Another advised him to have surgery. Yet another told him to have chemotherapy. "It turns out they were all right," noted Dr. Duckworth, who practices in the Boston area. "I did nothing at first, then I got the surgery, then I got the chemotherapy."

He added that he learned a lesson for his own psychiatry practice from the conflicting medical advice he received: Accept that sometimes the best course of treatment is unclear.

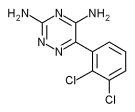

"So when we psychiatrists tell a person, 'I don't know whether we should give you lithium, Depakote, or Lamictal,' we are completely consistent with our brethren in medicine," Dr. Duckworth said.

When Carmen Febo-San Miguel, M.D., was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1993, she did her best to maintain her normal routine as a full-time family physician in Philadelphia while she underwent a mastectomy, 6 weeks of radiation therapy, and 6 months of chemotherapy.

For example, she scheduled her chemotherapy appointments for Friday afternoons and would be "miserable" all weekend from the effects, but she usually felt well enough to return to work on Monday. "As the months progressed, I wasn't able to bounce back as quickly," she said. "Sometimes I tried to go to work on Monday and had to come back home. Sometimes that was the case on Tuesday. I kept ... as close to my regular [routine] as I possibly could. The cancer was something else that was put on the agenda. It was unfortunate and it was unexpected, but it was one more thing that I needed to do."

Dr. Febo-San Miguel credits the support from her family, friends, and coworkers as instrumental to her recovery. "People rally to help you, especially if you're doing your share of what needs to be done," she said. "If you're not claiming some kind of advantage because you're sick, people understand that you're going through hard times and they chip in."

In 2001, she experienced a recurrence of her breast cancer that spread to her liver, ovaries, and abdominal cavity. "When I had the second recurrence,... my fear was, how spread is it? Is it in my bones? Is it in my brain? A regular patient may not even have those thoughts and anxieties."

She completed her last chemotherapy treatment in November 2002. She had no major complications, but has neuropathy in her hands and feet. "My hair is back and so is my weight, unfortunately," she said.

Today, Dr. Febo-San Miguel practices family medicine two half-days a week at Maria de los Santos Health Center in Philadelphia. She spends the rest of her time as executive director of Taller Puertorriqueno Inc., a Philadelphia-based cultural and educational center on Puerto Rican and Latino heritage.

She sees her physician for follow-up appointments every few months, has CT scans every 6 months, and has regular blood tests. A CT scan in the summer of 2004 showed no signs of cancer.

"I maintain the same attitude with myself that I maintain with patients," Dr. Febo-San Miguel said. "My approach is that I want people to know the reality, the extent of the problems that they're dealing with, but always maintain an optimistic view of the situation because the inner strength that people have can overcome incredible obstacles."

In February of 2000, William Tierney, M.D., was 25 days into his new job as director of the division of general internal medicine and geriatrics at Indiana University, Indianapolis, when he was diagnosed with stage IIIA non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Oncologists estimated that his chance of survival was 50-50. "I was fortunate enough to respond to the chemotherapy, but only about half of the people do," he said.

The most frustrating part of the experience, he said, was the chemotherapy-associated cognitive dysfunction he experienced over six courses of treatment. "I work in a world where I spend half of my life on e-mail," he said. "I'm managing about 16 problems simultaneously by jumping from one to another. When I was getting chemotherapy, each [jump] took an extraordinary amount of time and energy to make sense to me."

That reaction lasted for a year after his final chemotherapy treatment. Physical side effects include residual peripheral and autonomic neuropathy from the vincristine. "I can't feel my toes," he said, "and I have trouble walking in the dark because I don't have proprioception."

He missed only a few days of work during chemotherapy, but he said he wishes someone had given him two pearls of advice when he received his diagnosis: "First, find a health care provider you trust and do everything that person tells you," said Dr. Tierney, who is also coeditor of the Journal of General Internal Medicine. "Don't second-guess them. Do what you're told."

Second, admit that you have an illness. "I tried not to alter my schedule," he said. "I tried to do all the things I normally did until I dropped from exhaustion."

He recommends making a list of all the important things you do in a routine work week and sorting them by priority. Write down the number of hours required for each item. Once you reach 50% of the hours in your work week, "draw a line across the page and don't do anything below that line," advised Dr. Tierney, whose cancer is in remission. "Tell people that you're not going to be able to do [those things] for a year."

On his office desk, Dr. Tierney keeps a photograph that was taken when he had no hair on his head, a short-term side effect of chemotherapy. At that time--well aware that he might not live another year--"my priorities were much more family-focused and personally focused," he said. The more the likelihood of death recedes into the distance, "the more you start making compromises. I keep the picture on my desk to remind myself of the things that were important back then."

RELATED ARTICLE: Resources on Coping With Serious Illness

The following books and articles may help physicians who are facing a serious medical problem:

* "Blindsided: Lifting a Life Above Illness: A Reluctant Memoir," by Richard Cohen (New York: HarperCollins, 2004).

* "Writing Out the Storm: Reading and Writing Your Way Through Serious Illness or Injury," by Barbara Abercrombie (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2002).

* "When the Physician-Researcher Gets Cancer: Understanding Cancer, Its Treatment, and Quality of Life From the Patient's Perspective," by William M. Tierney, M.D., and Elizabeth D. McKinley, M.D. (Medical Care 2002;40[suppl. 6]:III20-7).

* "Death Foretold: Prophecy and Prognosis in Medical Care," by Nicholas A. Christakis (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999).

* "Coping With Long-Term Illness," by Barbara Baker (London: Sheldon Press, 2001).

* "Handbook for Mortals: Guidance for People Facing Serious Illness," by Joanne Lynn, M.D., and Joan Harrold, M.D. (Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1999).

* "Chicken Soup for the Surviving Soul: 101 Healing Stories of Courage and Inspiration From Those Who Have Survived Cancer," by Patty Aubrey, Jack Canfield, and Bernie S. Siegel (Deerfield Beach, Fla.: Health Communications, Inc., 1996).

* "When Bad Things Happen to Good People," by Harold S. Kushner (New York: Avon Books, 1983).

By Doug Brunk, San Diego Bureau

COPYRIGHT 2005 International Medical News Group

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group