Clinical Question: Is lamivudine safe and effective for the treatment of hepatitis B infection in patients with advanced liver disease?

Setting: Outpatient (specialty)

Study Design: Randomized controlled trial (double-blinded)

Allocation: Uncertain

Synopsis: The authors identified adults with chronic hepatitis B infection who were hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive or HBeAg negative with detectable hepatitis B virus DNA and who had histologic evidence of advanced liver fibrosis (i.e., an Ishak fibrosis score of 4 or more on a scale of 0 to 6). Exclusion criteria included hepatocellular carcinoma, a serum alanine transaminase level more than 10 times the upper limit of normal, hepatic failure, autoimmune hepatitis, co-infection with hepatitis C or human immunodeficiency virus, anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocy-topenia. Allocation appeared to have been concealed through a central randomization process (although no details were given), and analysis was by intention to treat. Outcomes were assessed by a committee masked to treatment assignment. Most of the patients were men (85 percent) and almost all were Asian.

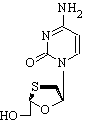

Participants were randomized to receive lamivudine in a dosage of 100 mg per day (n = 436) or placebo (n = 215) and were supposed to be followed for five years. However, the study ended prematurely once the benefit of lamivudine become apparent. The primary end point was a combined outcome called "time to disease progression," and included an increase in the Child-Pugh score of two or more points, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis with sepsis, renal insufficiency, variceal bleeding, hepatocellular carcinoma, or death caused by liver disease.

After a median treatment duration of 32 months, 34 patients in the lamivudine group and 38 patients in the placebo group had reached the primary combined end point (7.8 versus 17.7 percent; P = .001; absolute risk reduction = 9.9 percent; number needed to treat [NNT] = 10). Most of the benefit was attributed to fewer patients with an increased Child-Pugh score (3.4 versus 8.8 percent; P = .02; NNT = 18) and fewer cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (3.9 versus 7.4 percent; P = .05; NNT = 29). After reaching an end point, patients had the option of receiving lamivudine during an open-label continuation phase of the study.

During the double-blind phase, two deaths occurred in the lamivudine group compared with none in the placebo group. Serious adverse events were similar between groups (12 percent for lamivudine versus 18 percent for placebo; P = .09). However, when the open-label phase of the trial is included, more deaths occurred in the lamivudine group (12 versus four; statistical significance not reported). Approximately one half of the patients in the lamivudine group developed the YMDD mutation during treatment, thought to be caused by lamivudine. These patients were more likely to reach the primary end point than those who remained negative (11 versus 4 percent) and were more likely to die of hepatocellular carcinoma, but they still did better than patients receiving placebo.

Bottom Line: For every 10 patients with chronic hepatitis B infection and advanced liver disease who take lamivudine instead of placebo for 2.5 years, one fewer patient experiences progression of liver disease. Long-term use of lamivudine often triggers the YMDD mutation, and the benefit is attenuated in these patients. (Level of Evidence: 1b)

Study Reference: Liaw YF, et al. Lamivudine for patients with chronic hepatitis B and advanced liver disease. N Engl J Med October 7, 2004;351:1521-31.

Used with permission from Ebell M. Lamivudine slows progression in Hep B with advanced fibrosis. Accessed online November 24, 2004, at: http://www.InfoPOEMs.com.

COPYRIGHT 2005 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group