Hospitalization rates for patients with community-acquired pneumonia vary widely. A clinical prediction rule based on the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) attempts to standardize care by grouping patients standardize care by grouping patients into five risk categories based on predicted 30-day mortality. General agreement exists that patients in high-risk classes IV and V should receive inpatient treatment. However, controversy remains regarding the optimal treatment setting for patients in lower-risk classes II and III, who account for up to one half of all hospitalizations. Carratala and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial to compare outcomes of inpatient and outpatient treatment of patients in PSI risk classes II and III.

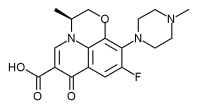

The study population consisted of 224 patients who were at least 18 years of age and had received a diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia (PSI class II or III) in the emergency departments of two tertiary care hospitals. Patients were excluded from the study if they were hypoxic, immuno-suppressed, or had a serious comorbid medical or psychosocial condition that mandated hospitalization. Patients also were excluded if they had received a quinolone antibiotic in the preceding three months or had a known allergy or other contraindication (such as pregnancy or breastfeeding) to quinolones. Following the collection of blood, sputum, and urine cultures, patients were randomly assigned to receive outpatient oral levofloxacin (Levaquin) 500 mg per day, or inpatient sequential intravenous and oral levofloxacin 500 mg per day.

All patients were reevaluated in the outpatient clinic at seven and 30 days after diagnosis. The primary endpoint was an overall successful outcome, defined as meeting seven predefined criteria (see accompanying table). Secondary endpoints were health-related quality of life and satisfaction with care, assessed with standardized questionnaires. Of the 224 patients originally enrolled, 203 completed the study protocol.

An overall successful outcome was recorded at the 30-day visit in 83.6 percent of outpatients and 80.7 percent of initially hospitalized patients. The one patient who died had received outpatient treatment and was hospitalized for intestinal ischemia two weeks after being diagnosed with pneumonia. Health-related quality of life was similar between groups, but outpatients reported greater satisfaction with their care than did inpatients (91.2 versus 79.1 percent).

The authors conclude that most patients in PSI classes II and III may be treated safely as outpatients, and that this treatment strategy improves patient satisfaction with care. In addition, they suggest that implementing this standard of care could produce significant economic savings because inpatient pneumonia treatment in the United States costs $6,000 to $7,000, whereas outpatient treatment costs less than $200. They caution, however, that this small study of low-risk patients was not powered to detect a difference in mortality.

Criteria for an Overall Successful Outcome

Clinical and radiographic resolution of pneumonia *

Absence of adverse drug reactions

Absence of medical complications during treatment

No need for additional hospital visits

No changes in initial antibiotic regimen with levofloxacin (Levaquin)

No subsequent hospital admission within 30 days of diagnosis

Absence of death from any cause within 30 days of diagnosis

*--Pneumonia was considered cured when all baseline signs (fever, hypothermia, altered breath sounds) and symptoms (cough, chest pain, dyspnea) resolved and infiltrates were no longer seen on chest radiography.

KENNETH W. LIN, M.D.

Carratala J, et al. Outpatient care compared with hospitalization for community-acquired pneumonia. A randomized trial in low-risk patients. Ann Intern Med February 1, 2005;142:165-72.

COPYRIGHT 2005 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group