A 41-year-old woman from Austin, TX, presented with a new-onset generalized seizure that lasted for 3 min. In the emergency department, she had no respiratory, cardiac, or GI symptoms. She gave a history of extensive travel to Central and South America, with the most recent trip having taken place 4 months earlier to a chicken farm in Panama. Her medical history was significant for hypothyroidism, and the only medication she was receiving was levothyroxine sodium (Synthroid; Abbott Laboratories; Abbott Park, IL). She had received the bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccine as a child and had exposure to tuberculosis at the age of 12 years from a family member.

On physical examination, she was alert, oriented, and had no neurologic deficits. She was afebrile, and her vital signs were normal. Auscultation of the heart and lungs yielded normal findings. Laboratory tests revealed an elevated WBC count of 15,500 cells/[micro]L with 92% neutrophils and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 22 mm/h. The results of all other laboratory tests, including hemoglobin test, platelet count, serum chemistry analysis, coagulation profile, and urinalysis, were normal. Test results for HIV were negative. In the emergency department, she had another generalized seizure. An MRI of the brain revealed an enhancing lesion in the right parietal lobe with surrounding edema (Fig 1). A preoperative chest radiograph taken prior to diagnostic excisional biopsy showed mediastinal and bilateral hilar adenopathy. The lungs were normal (Fig 2). A CT scan confirmed intrathoracic adenopathy (ie, paratracheal and left prevascular) [Fig 3, top, A) and revealed adenopathy in the upper abdomen. There was a small focal punctate calcification in a left hilar lymph node (Fig 3, bottom, B). A craniotomy and excision of the right parietal lesion was performed.

[FIGURES 1-3 OMITTED]

What is the diagnosis?

Diagnosis: Disseminated Histoplasma capsulatum infection in an immunocompetent host

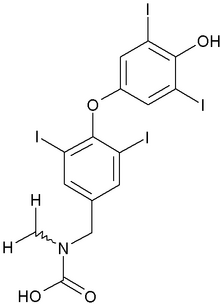

An excisional biopsy specimen of the right parietal lesion showed acute and chronic granulomatous inflammation. Special stains for fungi (Gomori methenamine silver and periodic acid-Schiff-fungus) revealed intracellular budding yeast that was morphologically consistent with the presence of H capsulatum within macrophages and multinucleated giant cells. Mucicarmine stain and special stains for bacteria (ie, Gram stain), acid-fast bacilli, and toxoplasmosis were negative. The findings of a brain tissue culture, serologic assays, and tests for urine antigen for histoplasmosis were negative. One month following the institution of antifungal therapy (ie, a loading dose of voriconazole followed by a maintenance dose of 200 mg bid), repeat chest radiographs showed a decrease in mediastinal and hilar adenopathy.

DISCUSSION

Histoplasmosis is caused by infection with H capsulatum, a thermal dimorphic fungus that is endemic to certain areas of North America, Central America, and South America. In the United States, the mycelial form is found in the soil along the central river valleys including those of the Mississippi, the Ohio, and St. Lawrence rivers. (1,2) Mycelial growth is stimulated by nutrients found in the excrement of bats and certain birds such as starlings, pigeons, blackbirds, and chickens. (3) Heavy exposure may occur in bat caves, chicken houses, or old attics or buildings where birds and bats roost. It is noteworthy that the patient's hometown of Austin, TX, is the site of the largest urban bat population in the United States, with approximately 1.5 million bats.

Pathogenesis

Infection results from the inhalation of airborne mycelial spores that germinate and convert to the yeast form in the lung at normal body temperature (37[degrees]C). Ingested by pulmonary macrophages, the yeast travel to hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes where access to the circulation allows for dissemination to various organs. Approximately 10 to 14 days after exposure, cellular immunity develops, and macrophages become fungicidal to clear an immunocompetent host of infection. (4) Caseating necrosis develops at the sites of infection in the lungs, lymph nodes, liver, spleen, and bone marrow, leading to fibrous encapsulation. Calcified granulomas and lymph nodes can occur at sites of infection after healing is complete. Any defect in cellular immunity may result in a progressive disseminated form of infection that can be lethal.

Clinical Manifestations of Disseminated Histoplasmosis

Disseminated histoplasmosis is rare and occurs primarily in patients with impaired cell-mediated immunity, particularly in those with HIV-infection with a CD4 lymphocyte count below 150 to 200 cells/[micro]L. In fact, since 1985 the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has added disseminated histoplasmosis as a defining illness of AIDS. Other conditions that predispose patients to the disseminated form of histoplasmosis include hematologic malignancies, (5) the use of high-dose corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents in organ transplantation, and the use of cytotoxic agents in the treatment of neoplastic and nonneoplastic conditions. (6) However, disseminated disease also may occur in individuals with no identifiable predisposing condition who have received a heavy inoculum.

The spectrum of illness associated with disseminated histoplasmosis ranges from an acute, rapidly fatal infection, usually in infants and severely immunocompromised individuals, to a chronic, intermittent course in immunocompetent individuals. In immunocompromised patients, fever is the most common symptom. These patients may present with weight loss, anorexia, malaise, cough, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. On physical examination, patients may have adenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, oral ulcers, and, less commonly, a maculopapnlar rash. (2) Patients with AIDS may develop disseminated intravascular coagulation, hypotension, and meningitis. Laboratory evaluation may reveal pancytopenia and abnormal liver function test results due to involvement of the bone marrow and liver. In contrast, in immunocompetent patients, the symptoms are typically mild and intermittent, including low-grade fever, weight loss, and fatigue. Hoarseness, oropharyngeal ulcers, hepatosplenomegaly, and adrenal insufficiency may occur.

Radiologic Manifestations of Disseminated Histoplasmosis

Chest radiograph findings were normal in up to 50% of cases in one series. (7) The most common radiographic abnormality is multiple, small, diffuse nodular opacities. Adenopathy, although present in the majority of immunocompetent patients with acute histoplasmosis, is infrequently seen in immunocompromised patients with disseminated disease. Pleural effusions are infrequent.

Approximately 10 to 20% of patients with disseminated histoplasmosis have CNS symptoms. Most of these patients do not have symptoms referable to the respiratory system. CNS involvement can manifest as meningitis, brain masses, diffuse encephalitis, and cerebral emboli associated with endocarditis. (8)

Diagnosis of Histoplasmosis

The diagnosis of histoplasmosis can be made by culture, fungal stains, and detection of serum antigens and antibodies. Skin testing is rarely used as positive results are common in endemic areas. The "gold standard" is a culture, which is positive in 10% of patients with self-limited disease, 67% of those with chronic disease, and 80% of those with disseminated disease. (2) However, the 4-week incubation period required for culture is not practical in severe eases in which delayed treatment may be fatal. Fungal staining of tissue and blood is rapid but has a lower sensitivity, than culture or antigen detection. The detection of antibodies to H capsulatum is rapid and sensitive, but false-negative results can occur iii immunocompromised patients and during the first 6 weeks following exposure. False-positive results can occur with cross-reactivity to other fungi, especially blastomyces and aspergillus. Additionally, antibody titers can stay elevated for years after exposure, and it may be difficult to differentiate active infection from past exposure. The detection of H capsulatum polysaccharide antigen is both rapid and sensitive in the diagnosis of disseminated disease, the testing of both urine and serum produces the best diagnostic yield. Because antigen levels decrease with treatment, this method is also useful in monitoring therapy.

Treatment of Histoplasmosis

Treatment recommendations vary with severity of illness and the immune status of the host. Antifungal therapy is indicated in patients with chronic and disseminated disease, and in those with prolonged or severe acute pulmonary infections. Treatment may include therapy with itraconazole or amphotericin B, with the addition of antiinflammatory agents and corticosteroids as adjuncts in certain cases. AIDS patients require lifelong maintenance itraconazolw therapy to prevent relapse. (9)

In summary, H capsulatum is an endemic mycosis in the United States. Infection is typically asymptomatic, however, the clinical spectrum ranges from a self-limited illness in the immunocompetent patient to potentially fatal disseminated disease in the immunocompromised patient. Treatment is indicated in all patients with disseminated disease as well as in those with severe or prolonged pulmonary infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT: We thank Gloria Mendoza for manuscript preparation, and Brooke Lening for imaging photography.

* From the Department of Diagnostic Radiology, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX.

REFERENCES

(1) Conces DJ Jr. Histoplasmosis. Semin Roentgenol 1996; 31: 14-27

(2) Goldman M, Johnson PC, Sarosi GA. Fungal pneumonias: the endemic mycoses. Clin Chest Med 1999; 20:507-519

(3) Bradsher RW. Histoplasmosis and blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis 1996; 22:S102-S111

(4) Wheat J. Histoplasmosis: experience tinting outbreaks in Indianapolis and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1997; 76:339-354

(5) Goodwin RA Jr, Shapiro JL, Thurman GH, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis: clinical and pathologic correlations. Medicine (Baltimore) 1980; 59:1-33

(6) Gurney JW, Conces DJ. Pulmonary histoplasmosis. Radiology 1996; 199:297-306

(7) Conces DJ Jr, Stockberger SM, Tarver RD, et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in AIDS: findings on chest radiographs, AJR Am J Roentgenol 1993; 160:15-19

(8) Wheat LJ, Batteiger BE, Sathapatayavongs B. Histoplasma capsulatum infections of the central nervous system: a clinical review. Medicine (Baltimore) 1990; 69:244-260

(9) Mocherla S, Wheat LJ. Treatment of histoplasmosis. Semin Respir Infect 2001; 16:141-148

Manuscript received October 2, 2003; revision accepted December 18, 2003.

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (e-mail: permissions@chestnet.org).

Correspondence to: Mylene T. Truong, MD, Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Box 57, The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: mtruong@mdanderson.org

COPYRIGHT 2004 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group