How good is American medical care? Attempts to answer this question usually center on hospital care, but a new study has assessed the quality of outpatient care using established quality indicators as the way to measure physician performance. After evaluating the care delivered in doctors' offices in 1992 and comparing it with care in 2002, researchers at Stanford University called for "greater adherence to evidence-based medicine." Their findings, which indicate considerable room for improvement, were published last month in the Archives of Internal Medicine.

The indicators of quality care used in this study apply to drug prescriptions, counseling, and tests that would be offered in a standard office setting, as opposed to procedures like colonoscopy and mammography that a primary care physician would refer out to a specialist.

After first looking at care delivered in 1992, the new study led by Jun Ma, MD, of Stanford University School of Medicine, found improvements had occurred in 2002 for only six quality indicators.

Here are the percentages of office visits that showed quality care improvements in 2002:

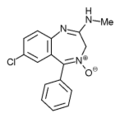

--Avoiding the inappropriate prescription of benzodiazepines (minor tranquilizers like Valium and Librium) for depression--83%, up from 47% in 1992;

--avoiding routine urine analysis for people without symptoms (because antibiotic treatment is inappropriate for symptomless urinary tract infections)-73%, up from 63%;

--correctly prescribing inhaled corticosteroids for asthma in adults-42%, up from 25%;

--correctly prescribing inhaled corticosteroids for asthma in children-36%, up from 11%;

--correctly prescribing cholesterol-lowering statin drugs for people with high cholesterol-37%, up from 10%;

--and avoiding the prescription of inappropriate drugs for the elderly-95%, up from 92%.

No Improvements for Other Indicators

Other indicators of quality care that did not show improvement are: counseling smokers to quit; offering dietary and exercise advice to people at high risk for heart disease; measuring blood pressure; and avoiding routine electrocardiograms (ECGs) for people without heart disease or heart symptoms.

Only 60% of visits ended with appropriately pr escr ibed bloodthinning drugs like warfarin for people with atrial fibrillation *; and only 58% appropriately prescribed a thiazide diuretic or beta-blocker drug to people with uncomplicated hypertension.

This assessment was funded with a research grant from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The study also looked at racial and ethnic disparities in outpatient care and found none. There were two exceptions, however: greater appropriate use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or so-called ACE inhibitor drugs (sold under more than two dozen different brand names in the U.S. and Canada) for congestive heart failure among blacks; and there was less unnecessary antibiotic use for the common cold among whites.

The basis for the study was the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey, which collects information about care delivered in private physician offices. Several sources were used as determinants of appropriate care, including the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and the Joint National Committee Guidelines for Treatment of Hypertension.

As for the determination of what constitutes inappropriate drugs for elderly people, the relevant quality indicators are based on a list that was put together in 1996 after researchers had documented widespread inappropriate prescribing for elderly people treated in hospitals, nursing homes, and physician office practices. It identified 11 prescription drugs (listed at right) that should never be taken by people over the age of 65 years.

In Worst Pills, Best Pills: A Consumer's Guide to Avoiding Drug-Induced Death or Illness, the Public Citizen Health Research Group "analyzes 538 drugs, including 181 pills you should not use and safer alternatives." Available in paperback, this book belongs in everyone's home library.

* "The heart's two small upper chambers (the atria) quiver instead of beating effectively. Blood isn't pumped completely out of them, so it may pool and clot. If a piece of a blood clot in the atria leaves the heart and becomes lodged in an artery in the brain, a stroke results." from the American Heart Association Web site

COPYRIGHT 2005 Center for Medical Consumers, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group