A factitious disorder is the intentional feigning or production of physical symptoms. It is estimated that 5 percent of physician-patient encounters may involve this diagnosis. Factitious disorder, commonly referred to as Munchausen syndrome, may not be suspected until after contradictory laboratory findings are found during the work-up for the feigned illness. Wallach reviewed the literature published since 1965 to identify the major features of factitious disorders.

Factitious disorders must be distinguished from other conditions such as malingering, conversion disorder, hypochondriasis and artifactual laboratory results. The hallmark of the disorder is factitious illness. In children, factitious illness may be produced by another person, almost always the mother. In this context, it can be classified as child abuse.

The fabricated history may appear plausible, but specific details are usually vague or inconsistent. Heroic deeds may be included in the history. Patients will often have extremely thick charts and clinical evidence of multiple surgeries. The usual time of onset is early adult life. The patients are typically demanding, hostile and attention-seeking. A remarkable aspect of the disorder is the willingness of patients to undergo endless laboratory testing and painful surgical procedures.

Recurrent themes appear in this disorder. A failure to suspect and diagnose the disorder is common. Factitious disorder is usually diagnosed during the process of evaluating the suspected illness that is being feigned. Scarce resources are wasted when unnecessary tests are ordered in pursuit of a diagnosis. Up to 12,000 patients with this disorder are hospitalized annually, at a cost of up to $40 million.

Patients have a general resistance to psychiatric therapy and, even if therapy is sought, the results are usually unsatisfactory with a high rate of recurrence. Clinicians easily become overwhelmed and angered by these frustrating patients. Factitious disorder has resulted in patient death, simulated rape and murder, although these instances are rare. The scope of the disorder crosses all areas of health care delivery and involves primary care physicians, sub-specialists and ancillary personnel.

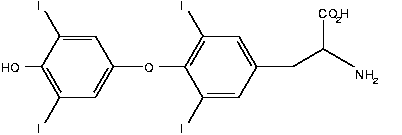

Laboratory tests are often the only way to diagnose a factitious disorder, and discordant results should heighten the suspicion of the diagnosis. Clinicians should be aware of and use the sophisticated laboratory tests that are currently available. These tests can accurately assay minute amounts of chemicals and foreign substances in the blood and aid in diagnosis of the disorder. The accompanying table lists examples of factitious disorder in which the laboratory plays a role.

The author concludes that laboratory studies may provide essential objective information for the clinician when factitious disorder is suspected. Early recognition can prevent unnecessary testing and procedures. The primary physician who is aware of new, sophisticated laboratory assays may be able to confirm an early initial diagnosis rather than making a diagnosis by exclusion and wasting valuable resources.

COPYRIGHT 1994 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group