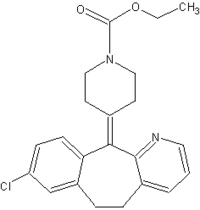

Loratadine, available as Claritin since 1993 and now available in several generic and over-the-counter formulations, is a popular nonsedating antihistamine used by many women of child-bearing age.

For some time, we have been counseling women that the older, first-generation sedating antihistamines are safe to use during pregnancy, based on the large amount of data available on these drugs--mainly collected from their widespread use as a treatment for morning sickness. We still do not have enough data on loratadine and other newer antihistamines to reach the same conclusion with certainty, however, even though these agents are members of the same class and presumably work on the same histamine H1 receptors.

The uncertainty regarding the reproductive safety of loratadine was complicated by the publication of a retrospective analysis from Sweden in 2002 suggesting that the risk of hypospadias in babies exposed in utero to loratadine was twice that of the general population.

In March, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published a study of a U.S. population of male infants that refuted the Swedish

findings.

The study used data from the National Birth Defects Prevention Study and focused on male infants born between October 1997 and June 2001. A total of 517 male infants with second- and third-degree hypospadias but no other major birth defects were compared with more than 1,000 controls born during the same period. There was no association between loratadine use during the month before conception and the first trimester of pregnancy and an increased risk of hypospadias (MMWR 53[10]:219-21, 2004).

As the authors note, the study has some limitations and does not provide "definitive information on the overall safety of loratadine." But it is a prospective, more carefully designed study that addressed the degree of hypospadias. In the Swedish study, the severity of hypospadias could not be determined, and the researchers did not control for family history of hypospadias and other variables. Hypospadias is a difficult end point to measure because it is quite common, occurring in about 7 of 1,000 male infants born in the United States, so it is important to include an appropriate control group before linking it to drug exposure.

Supporting the CDC's findings are two other recent studies, the first controlled prospective studies examining the use of loratadine in early pregnancy. These two studies also found no association between hypospadias and prenatal exposure to loratadine.

The first was a Motherisk study of women from Canada, Italy, Israel, and Brazil who were followed after they called a teratogen information service (TIS) during early pregnancy or while planning a pregnancy. Pregnancy outcomes were similar among the 161 women who took loratadine during the first trimester (a mean total dose of 159.9 mg), including 11 who took loratadine throughout pregnancy, and 161 similar women who had taken nonteratogenic drugs. The rate of major malformations was also similar in the two groups, and there were no reports of hypospadias among male infants (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 111[3]:479-83, 2003).

In the second study, which followed 210 pregnant women in Jerusalem who had used loratadine (mostly in the first trimester) and had called the Israeli TIS, no cases of hypospadias were reported among male infants. Moreover, the rate of congenital anomalies was not significantly different between this group and 267 infants exposed in utero to other oral antihistamines, or 929 infants exposed to nonteratogenic drugs (J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 111[6]:1239-43, 2003).

When considered together, these three studies suggest that if there is an increased risk of hypospadias associated with prenatal exposure to loratadine, it is minimal. Clearly, we need more data on loratadine and the other newer antihistamines. We have several hundred cases, but we would prefer to have thousands of cases and are continuing to enroll patients in our study. But for now, the available data are quite reassuring. As the authors of the CDC study pointed out, their results are not definitive, but I believe they are reassuring.

Physicians can counsel patients that, at least so far, there is no evidence that this particular medication causes any major malformation: in addition, it belongs to a class of drugs that have not been associated with major problems in millions of exposed women.

BY GIDEON KOREN, M.D.

DR. GIDEON KOREN, professor of pediatrics, pharmacology, pharmacy, medicine, and medical genetics at the University of Toronto, holds the Research Leadership in Better Pharmacotherapy During Pregnancy and Lactation. He is director of the Motherisk Program, a teratogen information service at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto.

COPYRIGHT 2004 International Medical News Group

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group