Clinical question Does intravenous lorazepam prevent recurrent seizures in patients with uncomplicated alcoholism presenting to the emergency department with a generalized seizure?

Background Alcohol withdrawal seizures are a common clinical problem in patients with chronic alcoholism, and are a leading cause of first seizures in adulthood. Benzodiazepines are effective in the primary prevention of alcohol withdrawal seizures; phenytoin is not. Previous studies of drugs that may prevent recurring seizures during withdrawal (secondary prevention) are lacking.

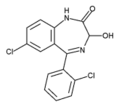

The benzodiazepine lorazepam can be given parenterally and has beneficial pharmacologic characteristics. Favoring safety are its short half-life unaffected by renal or hepatic dysfunction and its minimal respiratory and circulatory system side effects. Favoring efficacy is its limited tissue distribution that actually enables it to have a longer period of effectiveness in preventing seizures than diazepam.[1]

Population studied Adults with chronic alcoholism who presented to either of 2 urban emergency departments were enrolled if they had a witnessed generalized seizure. Over 21 months, 186 of 229 total patients were enrolled in the study: 78 patients consented on presentation; 108 patients consented only after treatment had been administered. They were initially unable to give informed consent because of intoxication or post-ictal confusion.

Exclusions were made before enrollment for laboratory abnormalities, including: glucose levels [is less than] 60 mg/dL, sodium levels [is less than] 120 mmol/L or [is less than] 160 mmol/L, calcium levels [is less than] 6.0 mg/dL, urea nitrogen levels [is less than] 100 mg/dL, or creatinine levels [is less than] 10 mg/dL. Evidence of the use of drugs that could increase seizures (eg, cocaine) or prevent seizures (eg, anticonvulsants, except phenytoin), was also a criterion for exclusion. Radiography was performed only if necessary. Patients were excluded if they showed evidence of trauma, mass lesions, or epilepsy. Forty-two patients had medical exclusions. One did not consent. In addition, 16 patients were excluded after enrollment, most of these because they developed moderate or severe signs of alcohol withdrawal that required treatment. They were included in the intention-to-treat analysis.

Study design and validity This was a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Study subjects were randomized to 1 of 2 groups: lorazepam 2 mg intravenously to prevent a recurrent seizure or usual care consisting of intravenous saline (with dextrose, if not contraindicated) and supplementation of magnesium, thiamine, and multivitamins. Patients had 6 hours of continuous electrocardiography and oximetry monitoring, and blood pressure recordings every 15 minutes. They were referred to a detoxification unit if they did not have an indication for hospitalization after the observation period.

The 2 groups had no significant differences in their demographics, typical alcohol consumption, average time of abstinence, time until seizure, time to treatment, alcohol levels, other laboratory values, or rates of exclusion criteria.

The study design was elegant, simple, and should have excellent validity for demonstrating drug effect. The effectiveness of the design comes partly from a paradox that is not seen in most placebo-controlled prospective trials: Usual care in the placebo group is supportive only; in the treatment group the study drug is presumed to be safe and reasonable enough to give to impaired patients with their informed consent still pending.

Outcomes measured The primary end point was the recurrence of an additional seizure during the 6-hour observation period. Additional evidence of recurrent seizures was sought by reviewing the records of the ambulance service that transported 85% of the study patients. Documented transportation of study patients because of seizure within 48 hours of release was also considered a recurrence. Although not complete, these measures appear to be unbiased and valid estimates of additional seizures during the clinically vulnerable time period.

Results Only 3% of patients in the treatment group had recurrent seizures compared with 24% in the usual care group, either during the 6 hours of direct observation or within the subsequent 48 hours of monitoring ambulance records (absolute risk reduction = 21%; number needed to treat = 4.8; P [is less than] .001). There were no complications related to lorazepam treatment.

Recommendations for clinical practice This study presents high-quality evidence that 1 dose of intravenous lorazepam given to patients with chronic alcoholism after a witnessed seizure can substantially reduce their risk of another seizure. Recurrence is common with 1 in 4 placebo-treated patients. A large majority (82%) of patients who were considered met the broad inclusion criteria, suggesting that similar use of lorazepam in practice could benefit a significant number of patients, even in the presence of the modest laboratory abnormalities that are common to these patients. There was good evidence for safety, and since patients with repeated seizures are often admitted, use of lorezepam may reduce hospitalizations.

REFERENCE

[1.] Browne TR. The role of benzodiazepines in the management of status epilepticus. Neurology 1990; 40(suppl):32-42.

D'Onofrio G, Rathleve NK, Ulrich, et al. Lorazepam for the prevention of recurrent seizures related to alcohol. N Engl J Med 1999; 340:915-9.

COPYRIGHT 1999 Dowden Health Media, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group