BACKGROUND. We conducted an historical cohort study to evaluate the relative effectiveness of niacin and lovastatin in the treatment of dyslipidemias in patients enrolled in a health maintenance organization (HMO).

METHODS. To be eligible for this study, adults aged 18 years and older who were initially treated with either niacin or lovastatin between January 1, 1992, and December 31, 1993, were identified from pharmacy databases. Each potentially eligible member with a fasting lipid panel prior to initiation of drug therapy and with a second fasting lipid panel between 9 and 15 months after initiation of drug therapy was included in the study. A total of 244 patients treated with niacin and 160 patients treated with lovastatin had complete data and are the subjects of this report.

RESULTS. Patients initially treated with lovastatin had higher baseline mean cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels as well as higher rates of diabetes mellitus and heart disease than did patients initially treated with niacin. Lovastatin use was associated with a mean 25.8% decrease in LDL cholesterol, while niacin use was associated with a mean 17.5% drop in LDL cholesterol (t=3.19, P [is less than] .002). Niacin use was associated with a 16.3% improvement in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, while HDL-cholesterol levels in the lovastatin group improved 1.5% (t=4.74, P [is less than] .001). Niacin use was associated with an 18.4% improvement in triglycerides, while lovastatin use was associated with an 8% improvement in triglyceride levels (t=2.81, P=.005). Differences in LDL/HDL ratio from before treatment to follow-up were no different in the two groups of patients (t=-1.21, P=.22). A total of 46% of patients initially treated with either drug reached their treatment goals in accordance with those set by the National Cholesterol Education Program. Drug discontinuation rates were 73% for niacin and 52% for lovastatin at follow-up, which averaged 10.7 months in each group.

CONCLUSIONS. These results suggest that both niacin and lovastatin are effective in treating dyslipidemic patients in this care system, and that physicians appropriately use lovastatin more often for patients with higher baseline LDL levels and more comorbidity. The data also strongly suggest that establishing an organized, population-based approach to systematically identify, treat, and monitor patients with dyslipidemias may be the single most important intervention HMOs should consider for improving control of dyslipidemias on a population basis.

KEY WORDS. Dyslipidemia; health maintenance organization; niacin; lovastatin; outcomes research. (J Fam Pract 1997; 44:462-467)

Recent data convincingly demonstrate that correction of dyslipidemias leads to lower rates of fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular events, and death.[1-3] Recent guidelines published by several expert panels give specific recommendations on how to identify and treat dyslipidemias and define treatment goals for various patients with dyslipidemias.[4-6]

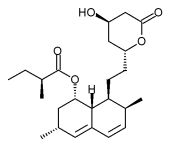

Many drugs are available for treatment of dyslipidemias in adults, and published guidelines allow practitioners considerable freedom in selecting among these drugs. Niacin and the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor lovastatin are both effective in lowering low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol but differ significantly in their mechanism of action, dosing, and cost.[7,8] We conducted an historical cohort study to compare the use and effectiveness of niacin and lovastatin in dyslipidemic patients enrolled in a large health maintenance organization (HMO).

METHODS

This study was conducted at a 240,000-member HMO in the Midwest. Members received their care at one of 19 staff model clinics and were referred as needed for care of dyslipidemias to a lipid clinic directed by an endocrinologist and staffed by nutritionists and pharmacists. Referral to the lipid clinic involved subspecialty assessment and development of a treatment plan. The patients were then generally returned to the care of their primary physician.

Computerized pharmacy records were used to identify HMO members over 18 years old who received initial treatment with either niacin or lovastatin at any time between January 1, 1992, and December 31, 1993. Any member who filled his or her prescription at an HMO pharmacy was identified. Not all prescriptions were filled in these pharmacies since some members over age 65 did not have drug coverage and many of these chose to fill their prescriptions elsewhere. Niacin does not require a prescription and can be obtained from a variety of sources, although it is also available at HMO pharmacies at competitive prices.

After members receiving initial treatment with lovastatin or niacin were identified from HMO pharmacy files, the medical records of these patients were reviewed. Members were included in the study only if they met all the following criteria:

1. The subject was continuously enrolled in the HMO and had received a prescription for either niacin or lovastatin between January 1, 1992, and December 31, 1993.

2. The subject had a fasting lipid panel that included cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglyceride, and calculated LDL cholesterol values as baseline before the initiation of the study drug.

3. The subject then had a second fasting lipid panel done between 9 and 15 months after initiation of the study drug.

There was no requirement that the member still be taking the study drug at the time of the follow-up lipid panel, since continuation of therapy and use of additional lipid-lowering agents were study outcomes of interest.

For each eligible member, a study period was defined from the date of initiation of treatment with the study drug to the date of a follow-up lipid panel 9 to 15 months later. If multiple lipid panels were done, the one done closest to the 12-month follow-up was selected. During the study period, all lipid panels from the 19 study clinics were done at one central, licensed clinical chemistry laboratory using a standard lipid assay method for total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides, with LDL cholesterol being calculated and not directly assayed. Specimens for fasting lipid profiles were accepted only if a 12-hour minimum fast was documented by laboratory personnel at the time of phlebotomy.

Data for analysis were obtained from medical record audits and included sex, date of birth, dates on which niacin, lovastatin, probucol, cholestyramine, gemfibrozil, or estrogens were started and stopped. (Lovastatin was the only HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor on the formulary before 1994.) Also noted was use of any other drugs known to affect lipids, dates and values from all lipid panels during the study period, dates of all inpatient and outpatient encounters, and reason for stopping niacin or lovastatin, if available. Data on cardiovascular risk factors, including the diagnosis of coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, or peripheral vascular disease, family history of heart disease, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, and other comorbid conditions were also obtained.

The data were then entered into an SAS database, reviewed for outliers or implausible values, and analyzed using SAS statistical software programs at HealthPartners Group Health Foundation. Parallel analyses of the original SAS database were conducted by USHH Outcomes Research and Management at Merck & Co, Inc, for verification.

Between January 1, 1992, and December 31, 1993, pharmacy files identified 721 members who had a prescription for niacin. Of these, 244 (34%) met the eligibility requirements outlined above. Of 670 members who had a prescription for lovastatin during the same time interval, 160 (24%) met eligibility requirements. Most excluded patients were ineligible because they had no follow-up lipid panel within the 9- to 15-month period required for this study, or because they were taking another lipid-lowering agent (most often gemfibrozil) at the time niacin or lovastatin was first prescribed.

Eligible patients included in either the niacin or the lovastatin drug group remained in that group for the main analysis. Subgroup results are reported for patients who were and were not taking the original drug at follow-up lipid panel, for patients who were and were not subsequently treated with additional major lipid drugs, and for patients with different LDL goal levels due to differences in cardiovascular risk-factor profiles.

Bivariate analysis was done using the chi-square statistic or t tests, depending on the nature of the variables being evaluated. Least-squares linear regression and ANCOVA modeling of the data were then done to adjust for age, sex, baseline dyslipidemia, use of other lipid-lowering drugs, and continuation or discontinuation of the study drug.[9]

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients initially treated with niacin and lovastatin. Of patients treated with lovastatin, 57% were men, while 54% of patients treated with niacin were women. Mean age of the two groups was similar but more members of the lovastatin group (39.9%) than the niacin group (30.2%) had received diagnoses of coronary artery disease. As expected, there were more patients with diabetes mellitus in the lovastatin group (18.5%) than in the niacin group (4.1%), since diabetes is a relative contraindication to the use of niacin.

Many HMOs are able to identify dyslipidemic members using computerized laboratory and pharmacy databases. An organized, population-based approach to systematically educate, monitor, and treat dyslipidemic patients could improve both clinical outcomes and long-term costs,[13,14] and could be driven in part by sophisticated clinical databases and interdisciplinary clinical care teams based either inside or outside the clinics. While further investigation of the effectiveness of this strategy is required, it is entirely plausible that effective organization of care may influence lipid outcomes more than the choice of drug does, when the problem of dyslipidemias is considered on a population basis. The magnitude of the improvement that is possible on a population basis is well documented in these data.

A second area for HMOs to evaluate is drug selection. In our study, physicians often selected an HMGCoA reductase inhibitor such as lovastatin for patients with established coronary artery disease or with very high baseline LDL levels. For patients with less severe baseline LDL elevations, less expensive agents such as niacin were often selected when education and dietary changes proved inadequate. Combination lipid drug therapy can also be considered for selected patients. Combination therapy may increase the effectiveness of lipid treatment and lower the cost of treatment, and the safety of combination therapy has received considerable support,[15-18] perhaps because lower doses of one or both drugs are often used.

The high drug discontinuation rates suggest that effective strategies to educate and follow up patients treated pharmacologically for dyslipidemias is a critically important aspect of care. The drug discontinuation rates in this study were 73% for niacin and 52% for lovastatin. One-year drug discontinuation rates reported in another managed care population were 45% for niacin and 13% for lovastatin.[19] One-year drug discontinuation rates as low as 4% for niacin[20] and 16% for lovastatin[21] have been reported in other published reports. It is likely that this is the key care element that might lead to an increase in the proportion of dyslipidemic patients reaching their target lipid levels in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by a grant from Merck & Co, Inc. The study was conducted and data analysis done at HealthPartners Group Health Foundation, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

REFERENCES

[1.] Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomized trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin survival study (4S). Lancet 1994; 344:1883-9.

[2.] Shepherd J, Cobbe SM, Ford I, et al. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med 1995; 333:1301-7.

[3.] Brown G, Albers JJ, Fisher LD, et al. Regression of coronary artery disease as a result of intensive lipid-lowering therapy in men with high levels of apolipoprotein B. N Engl J Med 1990; 323:1289-98.

[4.] National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel. Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Arch Intern Med 1988; 148:36-69.

[5.] National Cholesterol Education Program Second Report of the Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. NIH publication No. 93-3095, September 1993.

[6.] Institute for Clinical Systems Integration (ICSI). Health care guideline: treatment of dyslipidemias in adults. Bloomington, Minn: ICSI, 1996:1-34.

[7.] Manninen V, Tenkanen L Koskinen P, et al. Joint effects of serum triglyceride and LDL cholesterol and HDL cholesterol concentrations on coronary heart disease risk in the Helsinki Heart Study: implications for treatment. Circulation 1992; 85:27-45.

[8.] Illingworth DR, Stein EA, Mitchel YB, Dujovne CA, Frost PH, et al. Comparative effects of lovastatin and niacin in primary hypercholesterolemia Arch Intern Med 1994; 154:1586-95.

[9.] Kleinbaum DM, Kupper L, Morganstern H. Multivariate methods in epidemiologic research. Belmont, Calif: Lifetime Learning Publications, 1982.

[10.] Pronk NP, O'Connor PJ, Isham GJ, Hawkins CM.. Building a patient registry for implementation of health promotion initiatives in a managed care setting. HMO Practice 1997. In press.

[11.] O'Connor PJ, Rush WA, Pronk N, Cherney L. Identifying managed care members with diabetes mellitus or heart disease: sensitivity, specificity, predictive value and cost of survey and database methods. Centers for Disease Control: Tenth National Conference on Chronic Disease Prevention and Control Agenda, 1995:75.

[12.] O'Connor PJ, Rush WA, Rardin KA, Isham GJ. Are HMO members wiring to engage in two-way communication to improve health? HMO Practice 1996; 10(1):17-9.

[13.] Shaffer J, Wexler LF. Reducing low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in an ambulatory care system: Results of a multidisciplinary collaborative practice lipid clinic compared with traditional physician-based care. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155:2230-5.

[14.] National Cholesterol Education Program. Report of the Expert Panel on Population Strategies for Blood Cholesterol Reduction. Circulation 1991, 83:2154-232.

[15.] Vacek JL, Dittmeier G, Chiarelli T, et al. Comparison of lovastatin (20 ma) and nicotinic acid (1,2 g) with either drug alone for type II hyperlipoproteinemia Am J Cardiol 1995; 76:182-4.

[16.] Pasternak RC, Brown LE, Stone PH, Silverman DI, et al. Effect of combination therapy with lipid-reducing drugs in patients with coronary heart disease and "normal" cholesterol levels: a randomizd, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1996; 125:529-40.

[17.] Davingnon J, Roederer G, Montigny M, Hayden MR, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of pravastatin, nicotinic acid, or the two combined in patients with hypercholesterolemia Am J Cardiol 1992; 73:339-45.

[18.] Vega GL, Grundy SM. Treatment of primary moderate hypercholesterolemia with lovastatin and colestipol. JAMA 1987; 257:33-8.

[19.] Andrade SE, Walker AM, Gottlieb LK, Hollenberg NK, et al. Discontinuation of antihyperlipidemic drugs--do rates reported in clinical trials reflect rates in primary care settings? N Engl J Med 1994; 332:1125-31.

[20.] The Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Clofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA 1975; 231:360-81.

[21.] Bradford RH, Shear CL, Chremos AN, et al. Expanded clinical evaluation of lovastatin (EXCEL) study results: I. Efficacy in modifying plasma Lipoproteins and adverse event profile in 8245 patients with moderate hypercholesterolemia Arch Intern Med 1991;151:43-9.

Submitted, revised, January 17, 1997. From HealthPartners Group Health Foundation (P.J. O. and W.A.R.) and HealthPartners Lipid Clinic (D.L.T.), Minneapolis, Minnesota. Requests for reprints should be addressed to Patrick O'Connor, MD, HealthPartners Group Health Foundation, 8100 34th Ave South, PO Box 1309, Minneapolis, MN 55440-1309.

COPYRIGHT 1997 Dowden Health Media, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group