LSD is an acronym for lysergic acid diethylamide, also commonly known as acid. It is a powerful psychedelic drug that induces a temporary psychotic state that may include hallucinations and "deep insight" into the nature of things, say its adherents who made it into one of the counterculture's drugs of choice, especially during the 1960s. Developed by the CIA a decade earlier as a counter-espionage mind-controlling agent, LSD was initially intended for psychological torture during the Cold War. Psychiatrists later studied the drug as a means of observing their patients' uninhibited anxieties, and it was also used, with some success, to treat schizophrenia and autism in children, and chronic alcoholism and heroin addiction. In the 1950s, hundreds of subjects, including Hollywood and media celebrities and prominent artists, participated in experimental trips under the direction of Dr. Oscar Janiger, a Los Angeles-area psychiatrist, and other local therapists.

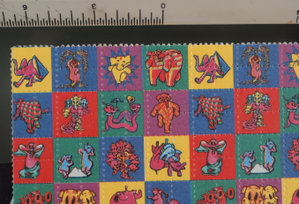

Not until LSD was widely ingested recreationally, though, at the urging of Dr. Timothy Leary and others, did it attain near-sacramental status among the avatars of mind-expansion after about 1965. "Dropping" acid evolved into a tribal act of civil disobedience, and some of the best minds of the twentieth century dabbled with LSD while seeking spiritual enlightenment. Many who advocate the unrestricted use of LSD charge that Sandoz cut off access to the drug for research purposes under pressure from prohibitionists who feared its impact on cultural transformation when it became a drug of choice in the youth community in the late 1960s. Some advocates believe reports of "bad trips" (psychotic episodes, going blind from staring at the sun, suicides by leaping from tall buildings) are exaggerated urban myths; they claim moderate doses of the drug do not produce such extreme effects, and that the draconian prohibition of the drug prevented researchers from devising safer regimens for ingesting it. In the 1980s and 1990s, "disco doses" of contraband LSD were often distributed via "blotter paper," sheets of cartoon-like decals that were chewed and ingested.

Dr. Albert Hoffman first synthesized LSD in 1938 at Sandoz Laboratories in Switzerland while researching ergot, the hallucinogenic rye fungus that is the natural source of lysergic acid. There he stumbled onto a powerful serotonin inhibitor he called LSD-25 (the twenty-fifth in a series of ergot derivatives) which produced intensely vivid hallucinations and altered states of perception. In 1943, he unwittingly absorbed the drug through his fingers, inducing a mild hallucinogenic state that he tried to duplicate several days later by deliberately dosing himself with 250 micrograms. Hoffman published his findings, but Sandoz soon lost interest in his experiments.

In 1942, however, the OSS (Office of Strategic Services, predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency) assembled a group of military scientists to examine the possibilities of a "truth drug" for deployment on political prisoners, and they tried a host of increasingly powerful pharmaceuticals to this end throughout the 1940s, often with dubious results. After World War II, the CIA consulted academics and psychiatrists as well as police crime labs to help expand its chemical-knowledge base. By the 1950s, the CIA had developed an "anything goes" attitude toward this objective, which eventually led to exploration of the shelved projects at Sandoz.

The CIA first used LSD on human subjects in 1951 and intensified its research, spurred by the growing fear of communist espionage. Researchers found that the effects of LSD could vary wildly according to personal and social expectations (the set) and the physical surroundings (the setting) during the "trip," so agents were directed to "dose" themselves and each other to become familiar with the drug's potential. In 1953 the CIA launched Operation MK-ULTRA, which authorized "surprise tests" on civilians, and by 1955 had opened a safe house in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco that lured unwitting subjects for a taste of the new drug in "real life" situations. Acid's unpredictable nature eventually led to more specialized hallucinogens, and the CIA discontinued the safe-house project in 1964, but by then LSD was already turning heads in the academic community. From the mid-1950s, Dr. Oscar Janiger carried out his experiments without accepting any funding from the CIA or the military. Instead, he charged subjects $20 per visit and used drugs supplied by Sandoz. Among the 900-odd visitors to his LSD "salon" were his cousin, the Beat poet Allen Ginsberg, writer Ana‹s Nin, Zen philosopher Alan Watts, novelist Christopher Isherwood, actors James Coburn, Dennis Hopper, and Jack Nicholson, and a group of Unitarian ministers who were disappointed that they had not experience hoped-for spiritual transcendence. Besides Dr. Janiger, other southern California psychiatrists who dispensed experimental doses to their clients included Dr. Arthur Chandler, who gave the drug to actor Cary Grant as a treatment for alcoholism; and Dr. Sidney Cohen, who "turned on" Henry Luce (of Time magazine) and Clare Boothe Luce, his wife. Luce perhaps achieved a better record of transcendence than did the Unitarian ministers when he reported an encounter with God on a golf course; his wife thought that LSD should be given only to the elite, saying, "We wouldn't want everyone doing too much of a good thing." In a 1998 interview, Dr. Janiger offered the drug-induced Eleusinian Mysteries in ancient Greece as a possible model for the creative use of LSD in contemporary culture: "The discussions I had with [Aldous] Huxley and [Alan] Watts and the others in those early years centered on the way our culture might institutionalize LSD ... and it would be very much like the Greek model."

Psychotropic treatment had caught the eye of Aldous Huxley whose book The Doors of Perception exposed the educated public to the possibilities of an intellectual, "psychedelic" experience. By 1957 experiments with LSD and the creative mind were being conducted by a clinical psychologist at Harvard named Timothy Leary who experienced a shamanic state and beatific visions while on acid. He and his colleagues claimed mass "tripping" could foster a new age of philosophical peace and freedom, and Leary spoke widely about the drug's positive applications, though other researchers dubbed these theories "instant enlightenment."

When the CIA abandoned serious LSD research, the scientific community lost its government supply of the drug, and Leary and others continued their research underground, supplying themselves with acid from a growing black market. There were many self-styled experts on LSD in the mid 1960s, many of whom had first been dosed in military-sponsored tests at Stanford, Harvard, and other universities, and most subscribed to the ideal of a unifying group trip. These communal experiments were tried on the east and west coasts of the United States, and it was Ken Kesey who mobilized this new wave of positive if absurdist religiosity based largely on the acid trip.

In 1959, Kesey, a recent Woodrow Wilson fellow at Stanford University, had been a $75-a-day guinea pig in LSD experiments at the Veterans' Administation Hospital in Menlo Park, where he remained employed as a mental-ward attendant after his part in the experiments were completed. His experiences there formed the basis for his celebrated 1962 novel One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. Two years after its publication, Kesey and a group of friends who dubbed themselves the Merry Pranksters set off on a cross-country trip (destination: the New York World's Fair) in a garishly painted old schoolbus, creating "happenings" along the way and extolling the virtues of psychedelia and hallucinogens as a bridge to harmony and understanding. The trip was itself memorialized in Tom Wolfe's 1968 book, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Kesey tried to unite the mystique of drug lifestyle with politically-conscious activism, and subsequent "acid tests" encouraged participants to confront the cosmic umbilical cord of the ego while high on LSD. Simultaneously, writers and musicians were "turning on" and psychedelicizing their work--most notably Allen Ginsberg, Hunter S. Thompson, Bob Dylan, The Beatles, and The Grateful Dead--further enhancing LSD's role as a folk remedy of sorts for the hippie nation, and a recreational enabler for both deep introspection and outrageous social protest. It has long been supposed by many Beatles fans that the band's 1967 song "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" (an acronym for LSD) was inspired by an acid trip, though Paul McCartney told Joan Goodman in a 1984 Playboy interview that the song was merely about "a drawing that John's son [Julian] brought home from school" and about one of his classmates named Lucy. Also in that year, Jack Nicholson, one of Dr. Janiger's subjects, included his experiences in his script for a 1967 low-budget film The Trip, that starred another subject, Dennis Hopper, and Peter Fonda.

The Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco--site of the government's earlier safe-house projects--became the hub of a psychedelic revolution. Here, black market acid was first sold on a mass scale, with acid manufacturers convinced they were performing an important public service. But just as the community began to throb with acid tests, free rock concerts, street theater, and full-blown psychedelia, LSD was made illegal in 1966 and Sandoz ceased its medical research distribution due to the bad press acid was receiving. Many blamed Leary's early outspokenness for the crackdown, but changes in attitude toward LSD research had already demonized the drug. Doctors now began speaking out publicly against the use of LSD, but this only served to inform more potential users (mostly young, well-educated, white middle-class users) about the drug. By the 1967 Summer of Love, it seemed as if all of America was "turning on" or trekking west to San Francisco where the action was, though the progenitors of acid culture were already burning out. The Haight, once an idyllic nexus, became a psychedelic tourist trap, and soon a pharmacopoeia of designer drugs (of which LSD was one of the weakest) emerged on the scene to bolster the waning euphoria.

In the wake of many highly-publicized, violent confrontations with authority, acid culture subsided by the early 1970s into a cabal of psychedelic drug devotees, convinced that they were being denied access to transcendence by fearful guardians of straight society. Much of LSD's early cultural history has been told in Jay Stevens's 1987 Grove Press book, Storming Heaven: LSD & the American Dream. By the 1990s, however, a nonprofit advocacy group called the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) was lobbying the Food and Drug Administration to approve medical studies of LSD as well as marijuana and other drugs like the popular Ecstasy. The group, which includes a number of prominent research scientists, was founded by Rick Doblin in the hopes of continuing Dr. Janiger's important but aborted research. As Dr. Janiger told an interviewer in 1998, "LSD didn't pan out as an acceptable therapeutic drug for one reason: Researchers didn't realize the explosive nature of the drug ... You can't manipulate it as skillfully as you would like. It's like atomic energy--it's relatively easy to make a bomb, but much harder to safely drive an engine and make light. And with LSD, we didn't have the chance to experiment and fully establish how to make it do positive, useful things."

At the end of the twentieth century, "hits" of LSD were most frequently available on colorful blotter-paper decals, permitting easy ingestion of "disco doses" far below those responsible for the well-publicized "bad trips" of earlier times. Artists like Mark McCloud have compiled a huge archive of these blotter-paper designs, which he considers an example of late-twentieth-century folk art. LSD is no longer tantamount to social defiance, but has become a metaphor for the search for enlightenment via ritualistic drug use in an urban, industrialized society, and also for the multifarious waves of cultural experimentation it inspired in the America of the 1960s. As a gateway to global transcendence at the millennium, LSD still inspires many testimonials on the World Wide Web's alt.culture sites, and researchers have begun to take a new and more favorable look at the once-demonized drug.

St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, 2002 Gale Group.