The lifetime prevalence of major depression in the United States is 17 percent.[1] In primary care, its prevalence rate is 4.8 to 8.6 percent.[2] Of all adult medical inpatients, 14.6 percent meet the diagnostic criteria for major depression.[3] Significant percentages of patients with uncomplicated depression are treated by family physicians. Untreated major depression results in significant impairment of social function and occupational activities, and may end in suicide.[4-6] Untreated depression also leads to the increased utilization of medical and substance-abuse services and causes academic difficulties in student populations.[6] The overall national economic burden of mood disorders is approximately $44 billion.[7]

Fortunately, two thirds to three fourths of patients improve with antidepressant pharmacotherapy, a rate comparable to outcomes in other medical disorders.[8] The greater penetration of health maintenance organizations has led to a greater emphasis on treating depression in the primary care setting by using antidepressant medications.[9] The effective treatment of major depression reduces mortality, and human pain and suffering, and yields significant social and economic benefits with improved quality of life.[10,11]

Diagnosis

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV)[6] includes nine symptoms in the diagnosis of major depression. For simplicity and ease of remembrance, two schematics are suggested. First, these nine symptoms can be divided into two clusters: (1) physical or neurovegetative symptoms and (2) psychologic or psychosocial symptoms (Table 1).[6] Second, the acronym "SIGECAPS," in association with depressed mood, may be used to diagnose patients with major depression. In this format, the nine symptoms are: depressed mood plus sleep disturbance; interest/pleasure reduction; guilt feelings or thoughts of worthlessness; energy changes/fatigue; concentration/attention impairment; appetite/weight changes; psychomotor disturbances, and suicidal thoughts.

To meet the criteria for the diagnosis of major depression, five of nine symptoms must be present for two weeks with at least one of the five symptoms being depressed mood or loss of interest/pleasure. In addition, the symptoms are not solely caused by general medical illness, medication, alcohol or drugs of abuse. Depression must also cause significant impairment in social, occupational or role functions.[6] Beck's Depression Inventory,[12] a self-rating depression scale with 21 items, may easily be used in the primary care setting as a screening instrument to quantify severity of depression and to measure progress once therapy is begun.

Work-up of Patients Before

Antidepressant Therapy

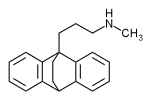

Before antidepressant therapy is initiated, the patient should have a directed history and physical examination. Consideration should be given to including routine laboratory tests such as complete blood cell count and chemistry panel, as well as tests to rule out thyroid dysfunction, diabetes and menopause. If the history and physical examination warrant it, further testing for connective tissue diseases (e.g., arteritis, systemic lupus erythematosus) or infectious diseases (e.g., acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, hepatitis, syphilis) may be indicated. An electrocardiogram is recommended in patients being considered for therapy with tricyclic antidepressants, maprotiline (Ludiomil) or amoxapine (Asendin), or if the patient is more than 40 years of age.

Treatment Considerations

Once the diagnosis of depression is established, assessments of the following 10 areas should guide a primary care physician to appropriate and safe selection of treatment options.

SUICIDE

Suicide risk is higher in depressed patients who are divorced or widowed, elderly, white, male or living alone, and those with associated chronic medical illness or psychotic symptoms. A past history of suicide attempt(s), a family history of completed suicide, and associated substance abuse also increase a depressed patient's risk of suicide attempt. Psychiatric consultation and treatment in a safe inpatient setting is recommended in these cases.

SECONDARY DEPRESSION

Medical conditions such as cancer[2] or endocrinopathy, medications (e.g., propranolol [Inderal]), and alcohol or drug abuse (e.g., cocaine withdrawal) can cause depression. The underlying cause should be treated, but if improvement in depressive symptoms fails to occur after four weeks of such treatment, depression should be independently diagnosed and treated.

BIPOLAR DEPRESSION

Bipolar depression is diagnosed by a past history of at least a single episode of mania (bipolar type I) or hypomania (bipolar type II). If no past history of mania or hypomania is elicited, a discrete episode of depression with hypersomnia without hyperphagia raises the index of suspicion for bipolar depression. Presence of bipolar depression would warrant treatment with a mood stabilizer such as lithium, valproic acid (Depakene, Depakote) or carbamazepine (Tegretol), with the possible addition of an antidepressant.

PSYCHOTIC DEPRESSION

This condition would be diagnosed by the presence of major depression with hallucination(s) or delusion(s). Psychotic depression generally requires combination pharmacotherapy with an antidepressant and an antipsychotic medication. Alternatively, monotherapy with amoxapine, which has mixed antidepressant and neuroleptic properties, may be used.[13]

MASKED DEPRESSION

Depression may present with a variety of "masks," such as a somatic mask (especially with gastrointestinal or hypochondriacal manifestations).[14] A cognitive mask or so-called pseudodementia may mimic dementia. An anxiety-disorder mask manifests as agitation or attentional difficulties. Normal physical, neurologic and laboratory findings in patients who are overusers of medical services should raise the index of suspicion for the diagnosis of depression.

SEASONAL DEPRESSION

This disorder presents as discrete episodes of depression during the fall and winter months (October through February). The patient gives a history of similar episodes in the previous fall and winter seasons. Light therapy with approximately 2,500 to 10,000 lux of full-spectrum light (10 to 20 times brighter than ordinary indoor light) for 30 to 60 minutes a day is recommended. The patient is advised to glance periodically at the light during each light exposure session.[15]

ATYPICAL DEPRESSION

Atypical depression is characterized by hypersomnia, hyperphagia with carbohydrate craving and weight gain, a longstanding pattern of interpersonal rejection sensitivity, leaden paralysis (i.e., heavy, leaden feelings in arms and legs) and reactivity of mood.[6] Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (Ma01s), such as phenelzine (Nardil), given at 45 to 90 mg per day in divided doses, are more effective for treatment of atypical depression than tricyclic antidepressants.[16] Recent data suggest that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may also be beneficial.

MAJOR DEPRESSION SUPERIMPOSED

ON DYSTHYMIA

Dysthymia is characterized by a low-grade depression lasting for two years or longer with periods of improvement lasting for two months or less. Major depression is treated with an antidepressant and/or cognitive-behavioral or interpersonal psychotherapy,[2,17] whereas dysthymia is treated primarily with psychotherapeutic techniques.

TREATMENT-REFRACTORY DEPRESSION

This condition is characterized by a history of therapeutic failure of two antidepressants used sequentially at an adequate dosage level for an adequate length of time. Referral to a psychiatrist for antidepressant augmentation therapy may be necessary. Stimulants, liothyronine (Cytomel) or simultaneous use of two or more antidepressants with or without a mood stabilizer (e.g., lithium), or electroconvulsive therapy may be prescribed.

ADJUSTMENT DISORDER

WITH DEPRESSED MOOD

This type of depression persists at least eight weeks past an identifiable loss. The treatment of choice for this condition is usually Psychotherapy, which emphasizes coping skills. If physical symptoms (Table 1) are present, an antidepressant medication may be warranted.

TABLE 1

Diagnostic Criteria for Major Depression

Cluster 1: physical or neurovegetative symptoms Sleep disturbance Appetite/weight changes Attention/concentration problem Energy-level change/fatigue Psychomotor disturbance

Cluster 2: psychologic or psychosocial symptoms Depressed mood and/or Interest/pleasure reduction Guilt feelings Suicidal thoughts

NOTE: Diagnosis of major depression requires at least one of the first two symptoms under cluster 2 and four of the remaining symptoms to be present for at least two weeks. These symptoms should not be accounted for by bereavement. In addition, these symptoms should not be caused by general medical illness, medications or alcohol/drug abuse, and must result in significant impairment in social and occupational function.

In addition to medication, many patients benefit from interpersonal or cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy[17] to repair relationships damaged by depression or to improve the patient's negative view of self, the past and the future. Brief counseling by a family physician can also improve compliance with treatment. Moreover, instilling hope, educating the patient and family members about depression and the nonhabit-forming nature of antidepressants, establishing a therapeutic alliance with the patient and the family, and alerting family members to a greater risk of suicide in the early stages of treatment will enhance the chance for a positive therapeutic outcome. In addition, the patient may be referred to self-help groups such as the National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association, 730 N. Franklin, Suite 501, Chicago, IL 60610; telephone: 800-826-3632, and the Depression Awareness, Recognition and Treatment Program of the National Institute of Mental Health, 5600 Fishers Lane, Room 10-85, Rockville, Md 20857; telephone: 800-421-4211 or 301-443-4140.

Selection of an Antidepressant

Once a physician decides to treat the patient with an antidepressant, the next significant task to be faced is to choose an antidepressant from the 21 such medications currently available. The choice of antidepressant must take into account the criteria listed in Table 2.

TABLE 2

Factors to Consider When Selecting an Antidepressant Agent

Patient's past history of response to an

antidepressant History of antidepressant response in a first-degree

relative of the patient Cardiovascular and medical status of the patient Target symptoms of depression Side effect profiles of agent Safety of agent following overdose Simplicity of use Cost Familiarity and comfort of the family physician

with the pharmacology of the antidepressant

agent Drug-drug interactions Drug-food interactions Drug-disease interactions

Information about the patient's past medical history and the family history of antidepressant response provides predictive data about future response and side effects. Depression is a chronic illness that often runs in families; therefore, this information should be sought. The cost of the drug, although not an overriding criterion for antidepressant choice, should be considered when there is greater flexibility of choice, as in younger, healthy, nonsuicidal patients, where the less expensive tricyclic antidepressants may be considered.

Target symptoms are important factors in choosing an antidepressant. For example, patients with insomnia, agitation and anxiety may benefit from a sedative antidepressant in divided doses, with the major dose administered at bedtime. Simplicity of use improves compliance. An antidepressant taken once a day at bedtime is more likely to be taken consistently than one requiring twice-daily (or more often) administration. Table 3[2,18-22] provides the dosage range and pharmacologic properties of various antidepressants.

[TABULAR DATA NOT REPRODUCIBLE IN ASCII]

One very important criterion for antidepressant choice is the side effect profile (Tables 4 through 6).[2,18-26] Cardiac side effects that occur with tricyclics, maprotiline and amoxapine are the result of a type 1A antiarrhythmic effect. These side effects include (1) sinus tachycardia; (2) supraventricular tachyarrhythmias; (3) ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation; (4) prolongation of PR, QRS and QT intervals; (5) bundle branch block; (6) first-, second- and third-degree heart block, and (7) ST- and T-wave changes.[24] Drugs with limited cardiac side effects are bupropion (Wellbutrin), SSRIs and MAOIs (Table 4).[2,18-25] Patients with known conduction system disease are at greater risk for serious cardiac toxicity when taking tricyclics, maprotiline or amoxapine.[24] Tricyclics should be avoided in the treatment of patients with ischemic heart disease, especially patients who have had a recent myocardial infarction.[25] Tricyclic overdose may cause death as a result of cardiac arrhythmia. In patients with a risk of suicide, the total dosage of prescribed tricyclic antidepressant should be limited to 1,000 mg (500 mg with nortriptyline [Pamelor]).

Orthostatic hypotension is caused by [alpha.sub.1] receptor blockade (Table 4). This blockade is frequently caused by tricyclics (the tertiary agents more so than the secondary agents), MAOIs, amoxapine, maprotiline, nefazodone (Serzone) and trazodone (Desyrel). A pretreatment orthostatic drop in blood pressure predicts treatment-related enhancement of such a drop. As a result, these drugs can cause dizziness and falls, especially in the elderly Venlafaxine (Effexor) can cause a sustained elevation of supine diastolic blood pressure. This effect is dosage-related, affecting 7 percent of patients at dosages of 200 to 300 mg per day and 13 percent of patients at dosages greater than 300 mg per day.[22(pp 2719-23)]

Sedation and weight gain caused by histamine [H.sub.1] receptor blockade are side effects that may occur with tricyclics and some heterocyclics. Protriptyline (Vivactil), SSRIs, bupropion, venlafaxine and MAOIs are less likely to cause troublesome sedation than other agents (Table 4). However, nonsedating drugs can be associated with insomnia, agitation and restlessness.

TABLE 4

Side Effects of Antidepressants: Cardiovascular, Sedative and Weight Gain

0 = note; + = low; ++ = moderate; +++ = moderate to high; ++++ = high.

Seizure threshold is lowered by most tricyclics and some heterocyclics, including amoxapine, bupropion and maprotiline (Table 5).[2,18-22] This side effect is most significant with maprotiline and clomipramine (Anafranil), where it is dosage-related. In the case of bupropion, high peak plasma levels have been associated with a higher risk of seizures. Therefore, the drug is administered in two to three divided doses, with a maximum dosage of 450 mg per day Recently, a sustained-release form of bupropion has been approved; twice-daily use may reduce the bolus effect. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration's advisory panel has approved the use of bupropion in patients attempting smoking cessation.

Gastrointestinal side effects, such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, are most often caused by drugs that block the reuptake of serotonin. Thus, the SSRIs, nefazodone, and venlafaxine are most likely to cause these effects (Table 5). Smaller increments of dosage increase during the early phase of treatment and administration with food can decrease the effects. These effects are often transitory and may improve after seven to 10 days of treatment.

Anticholinergic side effects are caused by blockade of muscarinic cholinergic receptors and manifest themselves as dry mouth, constipation, paralytic ileus and urinary retention. They may also cause photophobia and precipitate acute narrow-angle glaucoma. Tricyclics, amoxapine, maprotiline and mirtazapine (Remeron) frequently cause these side effects; the newer antidepressants and MAOIs have much less anticholinergic activity (Table 5).

[TABULAR DATA NOT REPRODUCIBLE IN ASCII]

Sexual dysfunctions like anorgasmia, decreased libido, erectile dysfunction and ejaculatory disturbances are also caused by potent serotonin reuptake inhibition and thus are most often associated with SSRIs and venlafaxine. Tricyclics, amoxapine, maprotiline and mirtazapine can cause erectile dysfunction. Trazodone can cause priapism, which may require emergent surgical intervention. Sexual dysfunction associated with SSRIs may respond to dose reduction or drug holidays. Adjunctive use of buspirone,[27] bupropion[28] or cyproheptadine (Periactin) in dosages of 4 to 12 mg taken one to two hours before coitus[29] may also be helpful. Erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction with tricyclics has been reported to respond to bethanechol (Duvoid, Urecholine), 30 mg taken one to two hours before coitus.[30]

Use in pregnancy, risk to fetus, excretion in breast milk and effects on the infant are reviewed in Table 6.[2,21-23,26] Bupropion, fluoxetine (Prozac), maprotiline, paroxetine (Paxil) and sertraline (Zoloft) are classified as category B,[22] having "no evidence of risk in humans."[23] Amitriptyline (Elavil, Endep) and imipramine (Tofranil) should be used only if the benefit during pregnancy is judged to outweigh the risks, as studies are lacking. Defects have been reported in infants born to women taking these medications. All other antidepressants are in category C.[23] The use of antidepressants during pregnancy requires weighing the risk-benefit ratio. Alternative treatment with electroconvulsive therapy may be considered.

Drug-drug interactions involving the antidepressants are important. The potentially fatal drug interactions with MAOIs and antiarrhythmic drugs are reviewed in Table 6. An additional area of concern is interaction caused by competing hepatic metabolic pathways via the microsomal [P.sub.450] isoenzyme system (Tables 7 and 8).[21,22,31-36] Drug-food interactions are less common but can be serious, such as the marked elevation of blood pressure in patients taking MAOIs who consume tyramine-rich foods. It is also well known that alcoholic beverages enhance the sedative effects of antidepressants and can impair a patient's ability to operate machinery.

[TABULAR DATA NOT REPRODUCIBLE IN ASCII]

TABLE 7

Cytochrome [P.sub.450] Isoenzyme Inhibition with Newer Antidepressants

ICI = inhibition clinically insignificant; ? = questionable inhibition; [+ or -] = clinical significance of inhibition not known; + = mild inhibition; ++ = moderate inhibition; +++ = substantial inhibition.

[TABULAR DATA NOT REPRODUCIBLE IN ASCII]

Although the ideal characteristics of an antidepressant have been described, none of the presently available antidepressants meets all the criteria.[18] The newer antidepressants (SSRIs, venlafaxine, nefazodone, bupropion) do have many ideal characteristics, such as fewer side effects, broader spectrum of efficacy, low lethality index after overdose, minimal pretreatment physical or laboratory work-up and comparable efficacy. The disadvantages of these antidepressants include the potential for serious drug interaction through inhibition of various hepatic cytochrome [P.sub.450] isoenzymes, cost and lack of defined therapeutic levels. Despite their disadvantages, these drugs should be considered first-line choices by family physicians in treating selected patients with major depression.

Long-Term Management

Evaluation of the effectiveness of therapy is judged by the earliest signs of improvement, such as sleep normalization, enhanced ability to care for self (e.g., grooming), improved ability to meet role obligations and increased energy. This stage is followed by improvement in other physical and psychologic symptoms. Beck's Depression Inventory[12] may be used to monitor progress.

MAINTENANCE ANTIDEPRESSANT THERAPY

Major depression is a chronic illness. Relapses and recurrences are frequent and, therefore, extended antidepressant therapy at a dosage level that brought about remission is recommended.[37] After the first, second and third episodes of major depression, recurrence risk is 50, 70 and 90 percent, respectively.[26] Following full symptom remission after the first episode of depression, a minimum of six to nine months of maintenance antidepressant therapy is recommended.[31] After remission of a second episode, maintenance therapy for at least one year3l is advisable, and after a third episode, indefinite antidepressant maintenance may be necessary to prevent future depression or suicide.[31] Also, patients with risk factors for recurrence (i.e., onset of depression before age 20, family history of depression, frequent relapses with severe episodes associated with suicidality and psychosis, poor recovery between episodes, dysthymia preceding major depressive episodes) may require life-long treatment.[31] Tapering over at least four weeks is recommended when the antidepressant therapy is to be stopped.

MONITORING ANTIDEPRESSANT LEVELS

A few antidepressants such as nortriptyline, desipramine (Norpramin), imipramine, amitriptyline and doxepine (Adapin, Sinequan) have relatively well-established blood levels (Table 3). Monitoring is recommended if the patient displays limited or no response to the prescribed antidepressant; if compliance is questionable; if the dosage has recently been changed; if the drug has a well-established therapeutic window (e.g., nortriptyline); if multiple drugs are used concurrently (with potential for drug-drug interaction); if the patient has a history of organ impairment and if a need exists for rapid titration. Children, adolescents and elderly patients should also be closely monitored.

PSYCHIATRIC CONSULTATION

Psychiatric consultation may be sought to enhance the safety and effectiveness of treatment if the patient has serious suicidal ideation, develops psychotic symptoms and poor judgment, develops acute manic symptoms during treatment of bipolar depression, has a poor or partial response to treatment with an antidepressant, refuses medications, necessitating alternative treatment such as electroconvulsive therapy, has a complicating physical illness or is concurrently using a drug with a potential for serious drug-disease or drug-drug interaction, or needs a safe inpatient psychiatric treatment program. Diagnostic clarification is also a reasonable reason for referral.

REFERENCES

[1.] Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1994; 51:8-19.

[2.] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Depression in primary care: detection, diagnosis, and treatment. Clinical Practice Guidelines no. 5. Rockville, Md.: Government Printing Office, 1993; AHCPR publication no. 93-0550.

[3.] Feldman E, Mayou R, Hawton K, Ardern M, Smith EB. Psychiatric disorder in medical in-patients. Q J Med 1987;63:405-12.

[4.] Johnson J, Weissman MM, Klerman GL. Service utilization and social morbidity associated with depressive symptoms in the community. JAMA 1992;267:1478-83.

[5.] Williams JW Jr, Kerber CA, Murlow CD, Medina A, Aguilar C. Depressive disorders in primary care: prevalence, functional disability, and identification. J Gen Intern Med 1995;10:7-12.

[6.] American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association, 1994:320-27.

[7.] Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER. The economic burden of depression in 1990. J Clin Psychiatry 1993;54:405-18.

[8.] Health care reform for Americans with severe mental illnesses: report of the National Advisory Mental Health Council. Am J Psychiatry 1993;150:1447-65.

[9.] Managed care's focus on psychiatric drugs alarms many doctors. Talk therapy is discouraged. The Wall Street Journal 1995 Dec 1;Sect A:1 and A:4.

[10.] Glass RM. Mental disorders. Quality of life and inequality of insurance coverage [Editorial]. JAMA 1995;274:1557.

[11.] Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Linzer M, Hahn SR, Williams JB, de Gruy FV III, et al. Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with mental disorders. Results from the PRIME-MD 1000 Study. JAMA 1995;274:1511-7.

[12.] Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961;4:561-71.

[13.] Anton RF Jr, Burch EA Jr. Amoxapine versus amitriptyline combined with perphenazine in the treatment of psychotic depression. Am J Psychiatry 1990;147:1203-8.

[14.] Walker EA, Katon WJ, Jemelka RP, Roy-Byrne PP. Comorbidity of gastrointestinal complaints, depression, and anxiety in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. Am J Med 1992:92(Suppl 1A):26S-30S.

[15.] Rosenthal NE. Diagnosis and treatment of seasonal affective disorder. JAMA 1993;270:2717-20.

[16.] Quitkin FM, Harrison W, Stewart JW, McGrath PJ, Tricamo E, Ocepek-Welikson K, et al. Response to phenelzine and imipramine in placebo nonresponders with atypical depression. A new application of the crossover design. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991;48:319-23.

[17.] American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for major depressive disorder in adults. Am J Psychiatry 1993;150(Suppl):1-26.

[18.] Richelson E. Pharmacology of antidepressants -- characteristics of the ideal drug. Mayo Clin Proc 1994;69:1069-81.

[19.] Cusack B, Nelson A, Richelson E. Binding of antidepressants to human brain receptors: focus on newer generation compounds. Psychopharmacology 1994;114:559-65.

[20.] Richelson E. Synaptic effects of antidepressants. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;16(Suppl 2):1S-7S.

[21.] Baldessarini RJ. Drugs and the treatment of psychiatric disorders: depression and mania. In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Molinoff PB, Ruddon RW, Gilman AG, eds. Goodman & Gilman's The pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996:431-59.

[22.] Physicians' Desk Reference. 51st ed. Montvale, N.J.: Medical Economics, 1997.

[23.] Lacy C, Armstrong L, Ingram N, Lance L, eds. Drug information handbook. 3d ed. Hudson, Ohio: Lexi-Comp, 1995:60-1415.

[24.] Hyman SE, Arana GW, Rosenbaum JF, eds. Handbook of psychiatric drug therapy. 3d ed. Boston: Little, Brown, 1995:78.

[25.] Glassman AH, Roose SP, Bigger JT Jr. The safety of tricyclic antidepressants in cardiac patients. Risk-benefit reconsidered. JAMA 1993;269:2673-5.

[26.] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Depression in primary care: detection, diagnosis, and treatment. Quick reference guide for clinicians no. 5. Rockville, Md.: Government Printing Office, 1993; AHCPR publicaton no. 93-0552.

[27.] Norden MJ. Buspirone treatment of sexual dysfunction associated with selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors. Depression 1994;2:109-12.

[28.] Labatte LA, Pollack MH. Treatment of fluoxetine-induced sexual dysfunction with bupropion: a case report. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1994;6:13-5.

[29.] Arnott S, Nutt D. Successful treatment of fluvoxamine-induced anorgasmia by cyproheptadine. Br J Psychiatry 1994;164:838-9.

[30.] Yager J. Bethanechol chloride can reverse erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction induced by tricyclic antidepressants and mazindol: case report. J Clin Psychiatry 1986;47:210-1.

[31.] Rush JA, Clayton P, Galle B, Baron D, Bernstein L Jr, Evans DL, et al. Length of antidepressant therapy: Consensus Conference statement March 3, 1995, Dallas, Tex. Little Falls, N.J.: Health Learning System, 1995:1-8.

[32.] Preskorn SH. What is the message in the alphabet soup of cytochrome P450 enzymes? J Prac Psychiatry Behavioral Health 1995;1:237-40.

[33.] Preskorn SH. Clinical pharmacology of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Caddo, Ok.: Professional Communications, 1996:81.

[34.] Ereshefsky L. Drug-drug interactions involving antidepressants: focus on venlafaxine. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;16(Suppl 2):37S-50S.

[35.] Ketter TA, Flockhart DA, Post RM, Denicoff K, Pazzaglia PJ, Marangell LB, et al. The emerging role of cytochrome P450 3A in psychopharmacology. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1995;15:387-98.

[36.] Nemeroff CB, DeVane CL, Pollock BG. Newer antidepressants and the cytochrome P450 system. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:311-20.

[37.] Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Perel JM, Cornes C, Mallinger AG, Thase ME, et al. Five-year outcome for maintenance therapies in recurrent depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49:769-73.

COPYRIGHT 1997 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group