Introduction

Iatrogenic allergic contact dermatitis to propylene glycol (PG) is an important factor to consider in recalcitrant dermatitis. PG is widely used as a vehicle in many different types of products, from personal care products, to over-the-counter medications, to prescription medications. It is of particular importance in patients being treated for dermatitis, as it is found in many topical corticosteroid preparations and emollients used in the treatment of dermatitis. In the cases described below, recognition of this contact allergy allowed successful therapy of recalcitrant dermatitis. Some of these patients were considered candidates for phototherapy or systemic medications. In these patients, all of whom had undergone therapy with multiple prior medications, a simple change in topical medications proved successful.

Case Reports

We describe 3 specific cases. All patients were patch tested using propylene glycol 30% in aqueous solution supplied by Chemotechnique Diagnostics, under occlusion for 48 hours in IQ chambers (inert polyethylene chambers supplied by Chemotechnique Diagnostics). The 72-hour readings are reported below with the scoring system used by the North American Contact Dermatitis Group. (1) Reactions of 1+ represent a definite positive reaction, 2+ indicate a strong edematous reaction, and 3+ indicate a spreading bullous response.

Patient 1 was a 68-year-old man with severely hyperkeratotic and fissured hand dermatitis for 8 weeks (Figure 1). His relevant reactions included a 3+ reaction to propylene glycol (Figure 2), a 3+ reaction to carba mix, a 2+ reaction to tixocortal pivalate, and a 2+ reaction to neomycin. We concluded that each of these reactions was relevant and contributory to his severe dermatitis. His reaction to carbamates was relevant, as he worked changing tires. However, he had stopped working for 4 weeks, and his dermatitis had continued to worsen during that time. He had been moisturizing with Cetaphil cream (contains PG) and had been using several different steroid ointments and creams, including Cutivate ointment (fluticasone proprionate 0.005%) with PG and generic clobetasol proprionate ointment 0.05%, which also contained PG. In addition, he was using rubber latex gloves on occasion to provide occlusion. He was prescribed Synalar ointment (fluocinonide ointment 0.05%), which is free of PG, and was asked to discontinue use of all previous emollients and medications. He was instructed to use pure Vaseline petroleum jelly as his only emollient. He was also instructed to avoid all rubber tires and rubber gloves. The condition was improved at his 3-week follow-up, and was significantly better at 3 months. At this point, he returned to his work of changing tires with the use of leather gloves. He continued frequent applications of Vaseline and occasional use of Synalar ointment. At a 6-month follow-up visit, he was clear (Figure 3).

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

[FIGURE 2 OMITTED]

[FIGURE 3 OMITTED]

Patient 2 was a 41-year-old woman with hand dermatitis for 6 years. She had noted worsening in the past 1 year. She noted no improvement with use of Psorcon E ointment (diflorasone diacetate 0.05%), which contains PG, or Ultravate ointment (halobetasol proprionate 0.05%), which also contains PG. She was moisturizing frequently with Cetaphil cream, which again contains PG. On testing, she exhibited a 1+ reaction to PG. Her other relevant reactions included a 2+ reaction to benzalkonium chloride, a 1+ reaction to chlorhexidine, and a 2+ reaction to nickel. The patient was a physician, and chlorhexidine was used in her workplace. The other reactions were of unclear relevance. She was counseled on avoidance, and at her 5-month follow-up visit, her hand dermatitis was resolved, and she had not used any topical steroids in months. She reported occasional flares. One such flare occurred after shampooing her son's hair, with the shampoo label confirming the presence of PG.

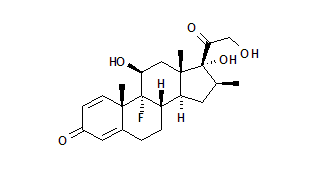

Patient 3 was a 57-year-old man with a history of atopic dermatitis in childhood. He had noted a recurrence of his dermatitis in the previous 2 years, starting on the legs and progressing to involve the trunk, the arms, and the face. The dermatitis had proved resistant to therapy with triamcinolone acetonide 0.1% cream, which contains PG, for months. However, he noted marked improvement after only 3 days of therapy with generic desoximetasone 0.05% ointment, which is free of PG, on the trunk and legs and with Desowen ointment (desonide 0.05%), also free of PG, on the face. Patch testing revealed a 2+ reaction to propylene glycol, a 2+ reaction to carba mix, and a 2+ reaction to ethyleneurea melamine formaldehyde resin. He was advised to continue using desoximetasone ointment as needed, and to use Aquaphor ointment, which is free of PG, as a moisturizer. It was felt that reactions to elastic and to formaldehyde in his clothing were playing a role, and he was counseled appropriately. When seen in follow-up 5 weeks later, he was doing very well, with clearance of the trunk, arms, and legs.

Discussion

Propylene glycol is widely used as a vehicle in emollients and topical medications. It is well recognized as a cause of iatrogenic contact dermatitis--contact dermatitis that is caused or potentiated by preparations or medications prescribed by the physician. This is likely due, in large part, to its frequent use in many over-the-counter and prescription dermatologic products, including many products prescribed for the treatment of dermatitis. For example, PG remains an important ingredient in many topical corticosteroid preparations, being found in every type of topical corticosteroid preparation, including creams, ointments, gels, lotions, solutions, foams, shampoo, and sprays.

Propylene glycol has a number of favorable properties, which explains its widespread use. It is a dihydric alcohol that is odorless, viscous, and readily miscible with water, acetone, and essential oils. At higher concentrations PG acts as a preservative due to antibacterial and antifungal effects. Of particular importance in the field of dermatology, propylene glycol has been found to enhance penetration of topical pharmacologic products. (2)

The North American Contact Dermatitis Group tests to aqueous PG at a concentration of 30%. They reported positive results in 3.8% of their population in the years 1996 to 19983 and 3.7% in the years 1998 to 2000.4 As propylene glycol is used so widely in skin care products, both therapeutic and cosmetic, it is an allergen that is increasingly difficult to avoid. Knowledge of its potential uses is of particular importance for physicians when prescribing topical medications, when recommending skin care products, and when counseling patients on avoidance.

A number of case reports describe the myriad ways in which PG may result in iatrogenic contact dermatitis.

Contact dermatitis may result from medications that are used to treat a wide range of dermatologic conditions, including dermatitis, fungal infections, viral infections, psoriasis, hair loss, neoplasms, and chronic venous insufficiency.

Cases of contact dermatitis to PG in topical steroid creams were first reported in the late seventies. (3-7) More recently, contact dermatitis to PG in inhaled corticosteroids used for allergic rhinitis has also been documented. (8)

The use of anti-infectives has also resulted in contact dermatitis, such as a case of contact dermatitis from PG in the topical antibiotic Rifocine, (9) several cases of PG allergy from acyclovir creams, (10-11) and allergy to ketoconazole. (12)

Cases of contact dermatitis to PG have also been described in such diverse categories of medications as topical 5-fluorouracil (13) and calcipotriene ointment. (14) Even exposures such as ECG gels prior to echocardiography have resulted in contact dermatitis. (15-17)

In a review of patients with chronic venous insufficiency, PG was found to be an important allergen due to its use as an ointment base, and due to its presence in modern wound dressings, particularly in hydrogel products. (18)

Topical minoxidil solution utilizes propylene glycol, 50% by volume, as a vehicle. Friedman et al found that a majority of patients reporting allergic symptoms such as pruritus and scaling of the scalp from minoxidil use were due in most cases to propylene glycol rather than to the minoxidil itself. (19) Fisher suggested use of glycerin as a vehicle in sensitive patients, and Scheman et al suggested polyethylene glycol 400 as an alternative. (20-21)

As newer medications and formulations are developed, there are an expanding number of potential sources of contact dermatitis to PG. PG is a particularly common ingredient in topical corticosteroids. In 1993, PG was found in 48 out of 82 corticosteroid creams, gels, ointments, and lotions in the United States. (2)

A review of A Pocket Guide to Medications Used in Dermatology 8th edition (2003) by Scheman and Severson (22) reveals that propylene glycol was found in almost 50% of approximately 141 corticosteroid products profiled. Corticosteroid gels, in particular, were likely to contain PG, with 75% of the products profiled containing PG. Among creams, 61% contained PG, while 60% of lotions contained PG and 43% of ointments contained PG. Corticosteroid foams represent a newer type of vehicle, and PG is found in both Olux foam (clobetasol proprionate) and Luxiq foam (betamethasone valerate). In addition, of the 372 emollients profiled, 29% have PG, and of hand sanitizers, 75% have PG.

Most cases of iatrogenic contact dermatitis resulting from PG will never undergo patch testing to confirm the allergen. Discontinuation of the offending medication may result in improvement. At other times, the patient with dermatitis does not respond to therapy and, therefore, is prescribed multiple medications before they finally, fortuitously, experience improvement. Based on our experience in the Baylor contact dermatitis clinic, the number of such cases is much more than indicated by the case reports found in the literature.

One of the hallmarks of contact dermatitis to propylene glycol is not necessarily worsening of the dermatitis with therapy, but rather dermatitis that does not respond to potent topical steroids. These cases often respond to a lesser potency topical steroid when provided in a vehicle lacking PG. The cases we describe here all represent multifactorial cases of recalcitrant dermatitis. In each case, avoidance of multiple allergens, initiation of topical corticosteroid therapy, appropriate protective measures, and the use of emollients were all necessary for improvement. However, all experienced dramatic improvement of their dermatitis with these relatively simple measures, such that none were required to seek systemic therapy or phototherapy. Recognition of the role of iatrogenic contact dermatitis permitted appropriate therapy that proved to be effective. Propylene glycol is only one of many allergens that may result in iatrogenic contact dermatitis; in patients with recalcitrant dermatitis, and particularly in those in which systemic therapy or phototherapy is being considered, patch testing is an important aspect of therapy.

References

1. Marks JG, DeLeo VA. Contact and Occupational Dermatology. Mosby-Year Book, Inc., St. Louis, 1997.

2. Rietschel RL, Fowler JF, eds. Fisher's Contact Dermatitis, 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2001; 232-236.

3. Marks JG, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group Patch-Test Results, 1996-1998. Arch Dermatol. 2000; 136:272-274.

4. Marks JG, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group Patch-Test Results, 1998 to 2000. Am J Contact Dermatol. 2003; 14:59-62.

5. Oleffe JA, Blondeel A, de Coninck A. Allergy to chlorocresol and propylene glycol in a steroid cream. Contact Dermatitis. 1979; 5:53-4.

6. Shore RN, Shelley WB. Contact dermatitis from stearyl alcohol and propylene glycol in fluocinonide cream. Arch Dermatol. 1974;109:397-9.

7. Hannuksela M, Pirila V, Salo OP. Skin reactions to propylene glycol. Contact Dermatitis. 1975; 1:112-6.

8. Bennett ML, et al. Contact allergy to corticosteroids in patients using inhaled or intranasal corticosteroids for allergic rhinitis or asthma. Am J Contact Dermat. 2001; 12:193-6.

9. el Sayed F, et al. Contact dermatitis from propylene glycol in Rifocine. Contact Dermatitis. 1995; 33:127-8.

10. Kim YJ, Kim JH. Allergic contact dermatitis from propylene glycol in Zovirax cream. Contact Dermatitis. 1994; 30:119-20.

11. Corazza M, et al. Propylene glycol allergy from acyclovir cream with cross-reactivity to hydroxypropyl cellulose in a transdermal estradiol system? Contact Dermatitis. 1993; 29:283-4.

12. Eun HC. Propylene glycol allergy from ketoconazole cream. Contact Dermatitis. 1989; 21:274-5.

13. Farrar CW, Bell HK, King CM. Allergic contact dermatitis from propylene glycol in Efudix cream. Contact Dermatitis. 2003; 48:345.

14. Fisher DA. Allergic contact dermatitis to propylene glycol in calcipotriene ointment. Cutis. 1997; 60:43-4.

15. Uter W, Schwanitz HJ. Contact dermatitis from PG in ECG electrode gel. Contact Dermatitis. 1996; 34:230-231.

16. Ayadi M, Martin P, Bergoend H. Contact dermatitis to a carotidian Doppler gel. Contact Dermatitis. 1987; 17:118-119.

17. Gonzalo MA, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to propylene glycol. Allergy. 1999; 54:82-3.

18. Gallenkemper G, Rabe E, Bauer R. Contact sensitization in chronic venous insufficiency: modern wound dressings. Contact Dermatitis. 1998; 38:274-8.

19. Friedman ES, et al. Allergic contact dermatitis to topical minoxidil solution: etiology and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002; 46:309-12.

20. Fisher AA. Use of glycerin in topical minoxidil solutions for patients allergic to propylene glycol. Cutis. 1990; 45:81-2.

21. Scheman AJ, et al. Alternative formulation for patients with contact reactions to topical 2% and 5% minoxidil vehicle ingredients. Contact Dermatitis. 2000; 42:241.

22. Scheman AJ, Severson DL. A Pocket Guide to Medications Used in Dermatology, 8th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2003.

Rebecca Lu BA, Rajani Katta MD

Department of Dermatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX

COPYRIGHT 2005 Journal of Drugs in Dermatology

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group