Summary points

Up to 50% of first episode genital herpes in the United Kingdom is attributable to herpes simplex type 1 virus, although recurrences are far more likely after infection with herpes simplex type 2 virus

Many patients and clinicians are unaware that oral sex is a common route of transmission of genital herpes infections

Transmission from asymptomatic individuals in monogamous relationships can occur after several years, causing severe psychological distress

The majority of patients with genital herpes simplex virus infections have symptoms and signs unrecognised by either themselves or their clinicians

Oral antiviral treatment should be given for primary or first episode genital herpes, and long term oral suppressive antiviral treatment is highly effective in reducing recurrences of symptoms in selected patients

Acquisition of a new herpes simplex virus type in the third trimester of pregnancy can have serious implications for the neonate and requires specialist intervention Clinical experience suggests that many doctors view genital herpes as an uncommon minor illness for which there is little effective treatment. Yet the converse is true. More than 28 000 cases of genital herpes were reported from clinics dealing with sexually transmitted diseases in England in 1998, and seroprevalence studies suggest that there are many more unrecognised infections. Patients often present having had frequent painful attacks of genital ulceration for many years, although effective antiviral drugs are available that dramatically reduce morbidity if used appropriately. In addition patients often believe that they are infectious only during symptomatic episodes, despite evidence that most transmission occurs from asymptomatic shedding of the virus.[1] This poor understanding may result in unnecessary morbidity for patients and their partners and inhibits efforts to reduce the spread of genital herpes.

Methods

We have concentrated on the clinical management of genital herpes. Sources of information included the UK national guidelines,[2] relevant references from Medline, data from recent international meetings, and personal experience of treating patients with genital herpes.

Clinical course and epidemiology

Herpes simplex virus is classified into types 1 and 2. Herpes simplex virus type 1 is widespread in the population and is the cause of herpes labialis; nevertheless, most infected individuals remain asymptomatic. Herpes simplex virus type 2 is mostly acquired sexually. Genital herpes can result from infection with either viral type.

After initial infection both types establish latency in the dorsal root ganglion, which innervates the affected epithelium. Latent virus is never cleared and is not affected by antiviral treatment. Reactivation results in either symptomatic disease or asymptomatic shedding of the virus. The initial infection may or may not cause symptoms and it is followed by seroconversion, with type specific antibodies becoming detectable 4-6 weeks after infection. The proportion of first episode genital herpes in the United Kingdom due to herpes simplex virus type 1 is increasing (up to 50% in some centres).[3] Possible reasons for this are a falling rate of orally acquired herpes simplex virus type 1 infection in childhood leading to increased susceptibility in sexually active adolescents, and an increase in the practice of oral sex by young people.[4] Recurrent episodes of genital herpes simplex virus type 1 are much less frequent than those experienced by patients infected with herpes simplex virus type 2, who account for 95% of recurrent cases.[5]

Varying seroprevalences of herpes simplex virus type 2 have been reported. Two London based studies showed prevalences of 10% in antenatal clinics, 3% and 12% respectively in men and women donating blood, and 23% in patients attending a clinic for sexually transmitted diseases in 1991-2.[6 7] In a study largely based outside London, prevalences of 3.3% in men and 5.1% in women have been reported.[3] This contrasts with a much higher frequency in the US population.[8]

Clinical spectrum of genital herpes

Primary or first episode genital herpes classically presents with blisters and sores, with local tingling and discomfort (figs 1-4). Some patients also report dysthesia or neuralgic type pain in the buttocks or legs and malaise with fever. Recent data, however, suggest that only 37% of patients who acquire herpes simplex virus type 2 have symptoms,[9] although overt disease may follow.

[Figures 1-4 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

Recurrences are generally milder than primary infection. It now seems that the clinical spectrum of disease can include atypical rashes, fissuring, excoriation and discomfort of the anogenital area, cervical lesions, urinary symptoms, and extragenital lesions.[10] Additionally, the common occurrence of asymptomatic shedding of the virus has been reported. This refers to the presence of the virus on epithelial surfaces in the absence of signs or symptoms and it occurs intermittently in most people infected with herpes simplex virus type 2.[11] In a prospective study of women with herpes simplex virus type 2 monitored by daily self swabbing, shedding of the virus was found on 28% of days by the sensitive technique of polymerase chain reaction and 8.1% of days by virus isolation.[12] The days on which shedding occurs cluster together and are more common in women with frequent recurrences of symptoms, especially in the first year of infection. The rate of shedding is much lower for infections caused by herpes simplex virus type 1.

Diagnosis

Genital herpes infection can be diagnosed by using virus culture, antigen detection, and polymerase chain reaction. Virus culture is the test of choice since it is relatively rapid (results within seven days), allows typing of the isolate (which is important for prognosis), and is widely available. Antigen detection with commercial assays is rapid, but kits cannot discriminate between the two viral types and this method has reduced specificity and sensitivity compared with virus isolation. All patients with genital herpes should have at least one virologically confirmed diagnosis. Type specific antibody tests may help identify those infected (with or without symptoms) with either virus type or both, but the limitations and role of these assays in diagnosis and management of genital herpes are not fully established.[13] The assays may, however, be complementary to virus culture for investigating patients with undiagnosed recurrent genital ulceration, demonstrating seroconversion in pregnancy, and investigating asymptomatic partners.[14]

Management

First episode genital herpes

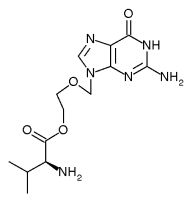

Patients presenting with first episode genital herpes often have widespread anogenital ulceration and severe pain, occasionally with retention of urine. The antiviral agents aciclovir, famciclovir, and valaciclovir have all been shown to be effective in reducing the severity and duration of symptoms, and choice of compound depends on cost and convenience of dosing schedule (table). Treatment should be initiated when a clinical diagnosis is made before laboratory confirmation, but swabs for viral identification and typing should be obtained before starting antivirals (box). Intravenous antivirals are no more effective than oral preparations, and topical applications of these drugs are ineffective. Regular bathing in saline, analgesia, and increased fluids to produce dilute urine are helpful. Although local anaesthetics applied topically may in theory cause sensitisation, this rarely happens in practice and they are helpful, particularly before micturition or defecation. With these measures it is normally possible to avoid catheterisation but occasionally catheterisation is unavoidable and the suprapubic route may be preferable to avoid extreme pain and the risk of ascending infection. Most patients with severe genital herpes feel depressed and tearful, even when ignorant of their diagnosis. Reassurance about the self limiting nature of the initial attack and support about future management is extremely effective in reducing distress. Information about the clinical course of the infection needs to be given early, but follow up for screening for other sexually transmitted infections, and ongoing counselling when patients have recovered, are required. Doctors may consider referring patients to a department of genitourinary medicine.

Recurrent genital herpes

After genital herpes has been diagnosed, patients (particularly those with herpes simplex virus type 2 infection) should be asked to keep a diary of recurrences and offered an appointment for long term follow up. Most recurrent attacks are much less severe than a first episode or primary attack. The options for treatment are bathing in saline, short courses of antiviral treatment for individual recurrences (episodic treatment), or long term suppressive antiviral treatment. The treatment modality depends on the severity and frequency of attacks and should be decided between the patient and doctor. Episodic treatment reduces symptoms by only 1-2 days and needs to be started as soon as possible after onset of symptoms. Ideally, patients should hold a stock of antiviral drugs for self treatment.

Suppressive treatment is generally offered to patients experiencing more than 6-8 recurrences a year. Definitive evidence of infection (usually a positive test result on viral cultures) is necessary before treatment, and a fixed term of suppression should be agreed (6 months or a year), after which treatment should be interrupted to observe the natural pattern of attacks. Individuals do experience a natural diminution in the frequency of their attacks over time or may become better psychologically adjusted and may no longer need suppressive treatment. If the frequency and severity of attacks do not diminish, suppressive treatment can be restarted. No full comparison of individual drugs is available--all are highly effective, and safety data are available for aciclovir for a period of more than 10 years. Suppressive treatment can make a major difference to the physical and psychological wellbeing of patients. Additionally, it has been shown to reduce shedding of the virus,[14] although data on a possible reduction in transmission are awaited.

Addressing patients' concerns

When patients are told they have genital herpes they commonly ask several questions--namely, how did I get this, how long have I had it, has my partner been unfaithful, is it incurable, and am I infectious?

It is helpful to discuss the possibility that infection can have been present without recognisable signs in them or their partners, so that recent infidelity is not necessarily implied. The chronic carriage of the virus should be put into context, perhaps with reference to other viruses such as varicella. Reassurance should be given that there is no evidence of the virus causing long term sequelae such as cancer and infertility (the role of herpes simplex virus in cervical cancer has been largely discounted, and yearly cervical smears are not required). Positive strategies for treatment should be emphasised. Knowledge that the tendency is for attacks to decrease with time (even if they are frequent initially) is often reassuring, as is information on the frequency of the infection in the population. Parallels with oral herpes, with which most people are familiar, are often helpful.

One of the most difficult areas is how to discuss the diagnosis with present or future partners. It should be emphasised again that a current partner may already have the virus, although they may be unaware of this. If this is so (type specific antibody testing may be helpful in this situation) superinfection is not thought to occur, and therefore safer sex precautions are probably not required unless otherwise indicated. For uninfected partners or those whose status is not known, methods to reduce the likelihood of passing on infection should be advised whether partners are aware of the diagnosis or not. This should include the avoidance of sexual contact during periods when any suggestive symptoms are present, and it is our practice to advise the use of condoms, although good data on their efficacy are lacking. Patients need reassurance that genital herpes is not transmitted by non-sexual contact and that no special precautions need be taken within the family other than normal hygiene measures.

The potential effects of genital herpes in pregnancy need to be discussed in detail, ideally with both partners. Type specific antibody testing may be helpful, and if this suggests that the woman is not infected with either virus type much effort should be directed to avoiding acquisition of genital herpes, especially in late pregnancy. Avoidance of both genital sexual contact (or at the very least strict use of condoms) and cunnilingus (if the partner has a history of oral herpes) may be considered in the last trimester.

As the ramifications of genital herpes are complex, the subject may need to be discussed on several occasions in a calm unhurried way and written information and sources of further support provided.

Genital herpes in pregnancy

The management of genital herpes in pregnancy should address the care of the pregnant women as well as reducing the risk of neonatal herpes (see fig A on the BMJ's website). A detailed review of this topic has been published.[15] Around 85% of cases of neonatal herpes result from perinatal transmission of the virus during vaginal delivery and can result in severe neurological impairment or death. This may be as a result of symptomatic or asymptomatic shedding of the virus in the genital tract. The risks are greatest when a woman acquires a new infection (with either virus type) in the last trimester of pregnancy. The neonate may then become infected from the mother's genital tract before she has produced type specific neutralising antibodies,[16] which seem at least partially protective when transferred transplacentally. The number of recognised cases of neonatal herpes in the United Kingdom is small, only 1 in 60 000 births (about 10 cases per year).[17] It is much more common in the United States (1 in 1800 to 1 in 8700).[18 19]

Women in the first two trimesters of pregnancy who have symptoms of first episode genital herpes should be investigated to confirm the diagnosis, and the use of aciclovir should be considered. Although aciclovir is not specifically licensed for use in pregnancy it has been used fairly extensively. Glaxo Wellcome (Middlesex) established a pregnancy registry in 1984, which showed no increase in the number of birth defects or any discernible pattern in defects in women exposed to aciclovir in pregnancy. Current practice in Britain is to proceed to vaginal delivery unless lesions are present during labour. If so, many obstetricians would consider delivery by caesarean section, although there is little evidence to support this approach. Some studies have found that suppressive aciclovir given in the last few weeks of pregnancy may reduce the rates of caesarean section.[20] Serial swabs for viral culture before labour are of no value in predicting shedding at term.

Women presenting with primary or first episode genital herpes in the last trimester are at greatest risk of transmitting infection to their babies and should be considered for delivery by caesarean section. If vaginal delivery does occur, mother and baby can be treated with aciclovir, babies requiring intravenous treatment. Suppressive treatment during the last few weeks of pregnancy is also an option. No good comparative data are available to help decide the best practice in this situation.[2 15]

Immunocompromised patients and drug resistance

Patients with compromised immune systems, such as those with advanced HIV infection, can develop persistent invasive lesions due to herpes simplex virus (see fig B on the BMJ's website).[21] The prevalence of virus resistant to aciclovir may reach 5%-10% in such populations,[22] and these viruses may be associated with considerable morbidity and mortality.[23]

When a poor response to initial nucleoside analogue treatment occurs, the dose should be increased to the maximum and treatment given intravenously. Swabs should be obtained for viral culture and drug susceptibility. Further non-response should prompt a change of treatment, guided by the resistance profile. In most cases, virus that is resistant to aciclovir is susceptible to foscarnet and this is considered by many to be the second line treatment of choice.[24] However, topical cidofovir also has efficacy in this situation.[25] Indeed many strains that are resistant to aciclovir are hypersensitive to cidofovir,[26] and this may be preferred in view of its relative lack of toxicity and ease of administration compared with intravenous foscarnet. Currently, topical cidofovir is not commercially available and requires preparation within the hospital pharmacy.

Conclusion

Genital herpes is a common infection that is frequently unrecognised or misdiagnosed. In our experience patients diagnosed with genital herpes often have received suboptimal treatment and poor advice concerning transmission. Many patients feel stigmatised and psychologically distressed as well as being in considerable pain. Effective counselling and adequate antiviral treatment (including suppressive treatment) can make a major difference to their quality of life.

Relative cost of antivirals for treating genital herpes. Costs per course

Adapted and modified with permission from the Clinical Effectiveness Group.[2]

Source of costing: British National Formulary, Sept 1999. (Different prices may be negotiated by NHS hospital trusts.)

Important terminology

* Primary genital herpes--genital herpes infection in an individual not previously infected with either herpes simplex virus type 1 or type 2

* First episode genital herpes--the first recognised attack of genital herpes in an individual previously infected by either herpes simplex virus type 1 or type 2

* Asymptomatic shedding--the shedding of virus from an epithelial surface in the absence of symptoms

* Recurrent genital herpes--recurring symptomatic attacks of anogenital herpes

Treatments for genital herpes

* All patients with primary or first episode genital herpes should receive oral antiviral and supportive treatment

* Suppressive antiviral treatment should be considered for those patients with more than six attacks a year

* Oral aciclovir, valaciclovir, and famciclovir are all effective agents for both first episode genital herpes and suppressive treatment--choice of agents is largely a matter of cost and patient acceptability

* Clear written information should be given to all patients infected with herpes simplex virus

* All patients should receive counselling on prevention of transmission and implications of infection with herpes simplex virus during pregnancy

Competing interests: SD and ST have received reimbursements for attending conferences, fees for speaking, and research funding from Glaxo Wellcome and SmithKline Beecham. DB and DP have received support from the same companies for Public Health Laboratory Service research. SD holds shares in SmithKline Beecham.

[1] Mertz GJ, Schmidt O, Jourden JL. Frequency of acquisition of first episode genital infection with herpes simplex virus from symptomatic and asymptomatic source contacts. Sex Transm Dis 1985;12:33-9.

[2] Clinical Effectiveness Group (Association of Genitourinary Medicine and the Medical Society for the Study of Venereal Diseases). National guidelines for the management of genital herpes. Sex Transm Infect 1999;75:24-8S.

[3] Vyse AJ, Gay NJ, Slomka MJ, Gopal R, Gibbs T, Morgan-Capner P, et al. The burden of infection with HSV-1 and HSV-2 in England and Wales: implications for the changing epidemiology of genital herpes. Sex Transm Inf 2000;76:183-7.

[4] Johnson AM, Wadsworth J, Wellings K, Field J. Heterosexual practices. In: Sexual attitudes and lifestyles. Oxford: Blackwell, 1994:110-82.

[5] Benedetti J, Corey L, Ashley R. Recurrence rates in genital herpes after symptomatic first-episode infection. Ann Intern Med 1994;121:847-54.

[6] Cowan F, Johnson A, Ashley R, Corey L, Mindel A. Antibody to herpes simplex virus type 2 as serological marker of sexual lifestyle in populations. BMJ 1994;309:1325-33.

[7] Ades AE, Peckham CS, Dale GE, Best JM, Jeansson S. Prevalence of antibodies to herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in pregnant women, estimated rates of infection. J Epidemiol Community Health 1989;43:53-60.

[8] Fleming DT, McQuillan GM,Johnson RE, Nahmias AJ, Aral SO, Lee FK, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 2 in the United States, 1976 to 1994 [see comments]. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1105-11.

[9] Andria GM, Langenberg A, Corey L, Ashley R, Wai Ping Leong MS, Straus S. A prospective study of new infections with herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1432-8.

[10] Koutsky L, Stevens CE, Holmes KK, Ashley R, Kiviat NB, Critchlow CW, et al. Underdiagnosis of genital herpes by current clinical and viral-isolation procedures. N Engl J Med 1992;326:1533-9.

[11] Wald A, Zeh J, Selke S. Virological characteristics of subclinical and symptomatic genital herpes infection. N Engl J Med 1995;333:770-5.

[12] Wald A, Corey L, Cone R, Hobson A, Davis G, Zeh J, et al. Frequent genital herpes simplex virus 2 shedding in immunocompetent women. Effect of acyclovir treatment. J Clin Invest 1997;99:1092-7.

[13] Taylor S, Drake S, Pillay D. Genital herpes, "the new paradigm" J Clin Pathol 1999;5 2:1-4.

[14] Wald A, Zeh J, Barnum G. Suppression of sub-clinical shedding of herpes simplex virus type 2 with acyclovir. Ann Intern Med 1996;124:8-15.

[15] Smith JR, Cowan F, Munday PE. The management of herpes simplex virus infection in pregnancy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;105:255-60.

[16] Brown ZA, Selke S, Zeh J, Kopelman J, Maslow A, Ashley RL, et al. The acquisition of herpes simplex virus during pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1997;337:509-15.

[17] Tookey P, Peckham CS. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection in the British Isles. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 1996;10:432-42.

[18] Brown ZA, Benedetti J, Ashley R, Burchett S, Selke S, Berry S, et al. Neonatal herpes simplex virus infection in relation to asymptomatic maternal infection at the time of labor. N Engl J Med 1991;324:1247-52.

[19] Gutierrez KM, Falkovitz Halpern MS, Maldonado Y, Arvin A. Epidemiology of neonatal herpes simplex virus infections in California from 1985 to 1995.J Infect Dis 1999;180:199-202.

[20] Brocklehurst P, Kinghorn GR, Carney O, Helson K, Ross E, Ellis E, et al. A randomised placebo controlled trial of suppressive aciclovir in late pregnancy in women with recurrent genital herpes infection. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1998;105:275-80.

[21] Bagdades EK, Pillay D, Squire SB, O'Neill C, Johnson MA, Griffiths PD, et al. Relationship between herpes simplex virus ulceration and CD4 cell counts in patients with HIV infection. AIDS 1992;6:1317-20.

[22] Harden EA, Rybak RJ, Hartline C, Cnann JW, Hodges-Savola CA, Wetherall NT, et al. Cross susceptibility patterns and neuro-virulence of acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex (HSV) isolates collected in a national surveillance study. Antiviral Res 2000;46:A78.

[23] Fox PA, Barton SE, Francis N, Henderson DC, Pillay D, Johnson MA, et al. Chronic erosive herpes simplex virus infection of the penis: a possible immune reconstitution disease. HIV Med 1999;1:10-18.

[24] Safrin S, Crumpacker C, Chaffs P, Davis R, Hafner R, Rush J, et al. A controlled trial comparing foscarnet with vidarabine for acyclovir resistant mucocutaneous herpes simplex in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med 1991;325:551-5.

[25] Lalezari J, Schaker T, Feinberg J, Gathe J, Lee S, Cheung T, et al. A randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled trial of cidofovir gel for the treatment of acyclovir-unresponsive mucocutaneous herpes simplex virus. J Infect Dis 1997;176:892-8.

[26] Chakrabarti S, Pillay D, Ratcliffe D, Cane P, Collingham K, Milligan D. Herpes simplex virus infections in allogeneic stem cell transplant recipients: risk factors for antiviral resistance and its prognostic significance. J Infect Dis 2000;181:2055-8.

Department of Sexual Medicine, Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham B9 5SS

Susan Drake consultant genitourinary physician

Stephen Taylor clinical research fellow

Central Public Health Laboratory, London NW9 5DF

David Brown consultant medical virologist

Public Health Laboratory Service, Antiviral Susceptibility Reference Unit, Division of Immunity and Infection, University of Birmingham, Birmingham B15 2TT

Deenan Pillay consultant medical virologist

Correspondence to: S Drake s.m.drake@bham. ac.uk

BMJ 2000;321:619-23

COPYRIGHT 2000 British Medical Association

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group