Little over a decade after its 1963 debut on the prescription-drug market in the United States, Valium had become a widely prescribed tranquilizer and began attracting media attention for what was seen as its rampant abuse. Reports found that many prescriptions for diazepam, Valium's generic name, were written by general practitioners, not mental-health professionals, and that a disproportionate number were given to women over 30 to control so-called "free-floating" anxiety.

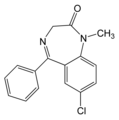

Valium, taken from the Latin word meaning "to be strong and well" and classified as an anxiolytic, or anxiety-dissolving drug, was developed in the New Jersey labs of pharmaceutical giant Hoffman-LaRoche by Dr. Leo Sternbach, who had also synthesized the compound that came on the market as Librium in 1960. Librium had been developed to compete with a rival company's popular tranquilizer, Miltown. All of these new drugs were targeted at middle-class Americans, many of whom were unlikely to visit a psychologist or psychiatrist for non-threatening depression or anxiety disorders because of the stigma attached to "mental illness." Valium, stronger than Librium and less bitter in taste, acted on the limbic system, the part of the brain that regulates emotional response and reaction. Because it was so potent, it could be formulated into much smaller doses than Librium, and unlike other tranquilizers, soothed without inducing drowsiness.

"Some Roche executives did not expect much of it," wrote Gilbert Cant of the New York Times Magazine about Sternbach's synthesizing of diazepam, "but a couple of them tried it on postmenopausal mothers-in-law whom they found insufferable, and were delighted by its calming effects." Valium came on the market in the United States in 1963. Users were cautioned not to operate heavy machinery or drive a car while taking it, and warnings about mixing it with alcohol were also blatant--the effects of both substances on the central nervous system were doubled when ingested together. Part of Valium's appeal lay in the belief that it was nonaddictive, and unlike other tranquilizers, almost impossible to be taken in a lethal dose by a suicidal person.

By 1974, 59.3 million Valium prescriptions were being written by doctors, and this figure, taken in conjunction with Hoffman-LaRoche's patent on diazepam, meant that Sternbach's employer had cornered 81 percent of the tranquilizer market in the country. The following year, a Vogue article entitled "Danger Ahead! Valium--The Pill You Love Can Turn on You," quoted extensively from Dr. Marie Nyswander, a New York City psychiatrist, who warned of its addictive properties. "Probably it would be very hard to find any group of middle-class women in which some aren't regularly on Valium," Nyswander declared. "Valiumania," as a 1976 piece authored by Cant in the New York Times Magazine was titled, termed it the most profitable drug in history, and questioned whether it had been "overmarketed" by Hoffman-LaRoche. Tellingly, only about 10 percent of prescriptions for Valium written in 1974 came from mental health professionals; 60 to 70 percent of Valium prescriptions came from the family doctor, gynecologists, or even more alarmingly, pediatricians. "Women, mostly those over 30, outnumber male users of Valium by 2-1/2 to one," Cant pointed out.

Valium also began to appear as an illegal "street" drug around 1975, the same year overall tranquilizer usage in the United States peaked. In 1978, it was estimated that about 20 percent of American women were taking Valium; nearly 2.3 billion of the pills were prescribed that year alone. The drug was so pervasive--and still considered relatively harmless--that it began to enter the vernacular. It was jokingly referred to as "Executive Excedrin," and made its way into comic scenes in movies such as Starting Over, as well as Woody Allen films and Neil Simon plays. An autopsy report found it in Elvis Presley's system when he died in 1977.

A 1979 bestseller, I'm Dancing as Fast as I Can, did much to alert the public to Valium's dangers. Its author, Barbara Gordon, was a successful, educated Manhattan career woman who became hooked on the drug over a nine-year period, and had to be hospitalized for her withdrawal symptoms. Reports of "rebound insomnia" from even light Valium usage began to appear in the press, and Senate subcommittee hearings later that year received widespread media coverage. Dr. Joseph Pursch--who, as head of the drug and rehabilitation program at Long Beach (California) Naval Regional Medical Center had treated former First Lady Betty Ford for her substance abuse problems--testified on the dangers of Valium. Physicians publicly confessed they had become addicted to the free samples mailed to them by Hoffman-LaRoche. An executive at the company defended the drug before the Senate committee, and asserted that its abuse was not Hoffman-LaRoche's fault, but lay rather at the feet of the doctors who overprescribed it and in the percentage of patients who became addicted to almost any substance. A physician also spoke on behalf of Hoffman-LaRoche, and asserted with complete seriousness that "to imply that the medicine is dangerous or highly addictive is not only incorrect, but it is a great disservice to millions of people whose lives are already troubled," Time quoted Dr. Michael Halberstam as saying.

As a compromise, the Food and Drug Administration forced Hoffman-LaRoche to include the caveat in its medical-journal advertisements for Valium as well as in the information provided to physicians stating that "anxiety or tension associated with the stress of everyday life usually does not require treatment with an anxiolytic drug." This warning went into effect in the summer of 1980, but a 1981 report on the possible link between Valium use and the rapid growth of cancer cells probably spelled a far worse death knell for the drug's popularity with the general public. The author of the study, Dr. David Horrobin, claimed he was forced out of a job at the University of Montreal because of his findings and his attempt to make them public. By 1982, the most prescribed medication in America was Tagamet, the anti-ulcer drug.

St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, 2002 Gale Group.