New drug treatments are emerging, but more clinical evidence is required

Bipolar affective disorder is a common condition which, among mental illnesses, ranks second only to unipolar depression as a cause of worldwide disability.[1] Classically, it manifests itself as repeated periods of illness with complete recovery. However, many patients have a poor outcome: a third suffer chronic symptoms and some 13-24% develop rapid cycling disorder, where four or more episodes occur within a year. The lifetime risk of bipolar disorder is at least 1.2%, with a recognised risk of completed suicide of 15%. Young men, early in the course of their illness, are at highest risk, especially those with a history of suicide attempts or alcohol abuse and those recently discharged from hospital. Despite its shortcomings, lithium has long been the mainstay of treatment for bipolar affective disorder. Several newer drugs have emerged over the past 10 years, but evidence of their effectiveness remains disappointingly thin.

Ideally, mood stabilisers should treat both mania and depression and prevent their recurrence. Importantly, treatment itself should not precipitate mania or depression or induce rapid cycling. Lithium has been used as a mood stabiliser in bipolar disorder for 50 years. It continues as a first line treatment in acute episodes and in prophylaxis, but doubts remain about its effectiveness in clinical practice. Some patients respond inadequately to lithium, especially those with rapid cycling disorder and those with mixed mania, where manic and depressive symptoms occur together. Its narrow therapeutic window necessitates frequent blood monitoring, limiting its use in some countries. Lithium discontinuation may precipitate recurrence, a serious problem in the poorly compliant.

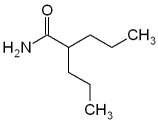

The anticonvulsants carbamazepine and valproate are established alternative and adjunctive treatments to lithium. Valproate is the most frequently prescribed mood stabiliser in the United States and is increasingly used in Europe. The mechanism of action of anticonvulsants in bipolar disorder remains unclear. Originally they were used when lithium was poorly tolerated or ineffective; now they are increasingly used as first line monotherapy, yet the evidence for their use remains incomplete. The efficacy of valproate in treating mania was confirmed in the largest placebo controlled trial in which it was studied,[2] but no randomised controlled trials have examined its effects in bipolar depression. Its use in maintenance treatment has been based on open data and one randomised controlled trial in a group of patients with heterogenous affective disorders.[3] Recently, a randomised controlled trial failed to show that valproate prolonged the time to recurrence of any mood episode over 12 months, although this result is questionable because of the methodological limitations of the study.[4]

The efficacy of carbamazepine in treating mania and bipolar depression and in prophylaxis has been shown in randomised controlled trials, but evidence for its acute efficacy in bipolar depression and overall prophylactic efficacy is not strong. Cochrane reviews on the efficacy of carbamazepine and valproate in bipolar disorder are under way.

All the established mood stabilisers appear to be more effective in treating and preventing mania than depression. Lithium is reported to have specific antisuicidal effects,[5] but few data are available on the antisuicidal effects of carbamazepine and valproate. Although valproate and carbamazepine may be more effective than lithium for mixed states and rapid cycling disorder, much treatment resistance remains. New medications for bipolar depression, mixed states, and rapid cycling disorder are urgently needed: new anticonvulsants and atypical antipsychotics are potential candidates.

The anticonvulsant lamotrigine has been shown to have acute efficacy in bipolar depression in two randomised controlled trials.[6 7] In the first placebo controlled trial conducted in rapid cycling disorder, lamotrigine improved the overall relapse rate.[8] Two placebo controlled trials failed to replicate open label evidence of gabapentin's efficacy in hypomania and mania.[7 9] Cochrane reviews on both these anticonvulsants in bipolar disorder are in progress.

Antipsychotics have long been used in bipolar disorder. Typical antipsychotics are effective in acute mania but may exacerbate postmanic depression. Little evidence supports their prophylactic use, which risks the induction of tardive dyskinesia. Placebo controlled studies of olanzapine and risperidone have shown the acute antimanic efficacy of both these atypical antipsychotics, although the effects of prolonged use are not yet clear. The prototype atypical antipsychotic, clozapine, is reserved for use in highly refractory cases of bipolar disorder.[10] Intriguingly, [Omega]-3 fatty acids showed mood stabilising effects in one small randomised placebo controlled trial; the underlying mechanism may be the inhibition of signal transduction in neuronal membranes.[11]

New non-pharmacological treatments such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and vagal nerve stimulation are emerging. Psychological treatments such as cognitive behavioural therapy target recognition of early warning symptoms and compliance with medication and may provide strategies for coping with illness and attendant psychosocial problems.[12]

The management of this common and often debilitating lifelong illness should be shared between primary care and general psychiatrists. Although many new acute treatments for mania have been evaluated in placebo controlled studies over the past 10 years, only a few have undergone evaluation of their prophylactic efficacy in long term randomised controlled trials. Clinicians and their patients need evidence based treatment strategies that produce complete sustained remissions and improve quality of life.

[1] Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Global mortality, disability, and the contribution of risk factors: global burden of disease study. Lancet 1997;349:1436-42.

[2] Bowden CL, Brugger AM, Swann AC, Calabrese JR, Janicak PC, Petty F, et al. Efficacy of divalproex versus lithium and placebo in the treatment of mania. The Depakote Mania study group. JAMA 1994;271:918-24.

[3] Lambert PA, Venaud G. Etude comparative du valpromide versus lithium dans la prophylaxie des troubles thymiques. Nervure 1992;5:57-65.

[4] Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, McElroy SL, Gyulai L, Wassef A, Petty F, et al. A randomised placebo-controlled 12-month trial of divalproex and lithium in treatment of outpatients with bipolar I disorder. Divalproex Maintenance Study Group. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:481-9.

[5] Goodwin FK. Anticonvulsant therapy and suicide risk in affective disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60(suppl 2):89-93; 111-6.

[6] Calabrese JR, Bowden CL, Sachs CS, Ascher JA, Monaghan E, Rudd CD. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of lamotrigine monotherapy in out-patients with bipolar 1 depression. Lamictal 602 study group. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60:79-88.

[7] Frye MA, Ketter TA, Kimbrell TA, Dunn RT, Speer AM, Osuch EA, et al. A placebo-controlled evaluation of lamotrigine and gabapentin monotherapy in refractory mood disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacology (in press).

[8] Calabrese JR, Suppes T, Bowden CL, Sachs CS, Swann AC, McElroy SL, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, prophylaxis study of Lamotrigine in rapid cycling bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry (in press).

[9] Pande AC. Combination treatment in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disorders 1999;1(suppl 1):17.

[10] Calabrese JR, Kimmel SE, Woyshville MJ, Rapport DJ, Faust CJ, Thompson PA, et al. Clozapine in the treatment of treatment-refractory mania. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153;759-64.

[11] Stoll AL, Severus WE, Freeman MP, Rueter S, Zboyan HA, Diamond E, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids in bipolar disorder: a preliminary double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gert Psychiatry 1999;56:407-12.

[12] Scott J. Psychotherapy for bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1995;167: 581-8.

A H Young professor of psychiatry

Karine A N Macritchie specialist registrar

Department of Psychiatry, Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 4LP

J R Calabrese director, mood disorders programme

Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, 11400 Euclid Ave, Suite 200, Cleveland, Ohio 44106, USA

AHY is funded by the Stanley Research Foundation and has received consultancy tees from Janssen. JRC is involved in advisory boards for the following pharmaceutical companies: Abbott, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, GlaxoWellcome, Janssen Cilag, Novartis, Parke Davis, Shire, Smith Kline, TAP Holdings, UCB Pharma, and Teva.

COPYRIGHT 2000 British Medical Association

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group