INTRODUCTION

Cocaine abuse continues to represent a significant problem, and its costs, in both economic and human terms, are enormous. Attempts to develop successful pharmacologic treatments have been disappointing to date. Depressive syndromes are prevalent in outpatients with cocaine dependence (CD) (1-4) and are associated with a poor prognosis (5). Cocaine withdrawal bears a striking similarity to the symptoms of depressive disorders, typically including exhaustion, hypersomnia, hyperphagia, depressed mood, as well as intermittent periods of cocaine craving (6). This suggests the hypothesis that antidepressant medications might be effective in initiating and maintaining abstinence from cocaine. Unfortunately, placebo-controlled trials using antidepressant medications in samples of cocaine-dependent patients not screened for depression have been largely unsuccessful (7-9). However, in several of these trials, favorable effects of medication on depressive symptoms were observed (10-12), and subgroup analyses suggested a favorable effect on cocaine use outcome in the depressed subsamples (7, 12). This suggests the hypothesis that antidepressant medications might be effective in the subset of cocaine abusers with depression. Analogously, several placebo-controlled trials support the efficacy of antidepressants in depressed alcoholics (13-15) and opiate addicts (16, 17).

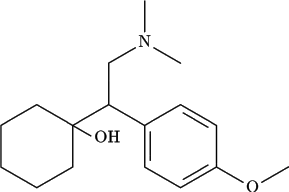

Here, we report what is, to our knowledge, the first pilot trial of the new antidepressant medication venlafaxine in cocaine-dependent outpatients with depressive syndromes. Venlafaxine has a unique chemical structure and mechanism of action. It and its metabolite O-desmethylvenlafaxine are potent inhibitors of the reuptake of 5-hydroxytryptophan and norepinephrine and are also weaker inhibitors of dopamine reuptake (18). Like other newer antidepressant agents, venlafaxine is well tolerated with fewer side effects than such older tricyclic antidepressants as desipramine and imipramine. Also, there is some evidence that it may have a more rapid onset of effect than the tricyclics, which generally require 2 to 4 weeks to begin action (19). We hypothesized that venlafaxine would be well tolerated and produce rapid improvements in both mood and cocaine use.

METHODS

Subjects were 13 outpatients with a DSM-III-R diagnosis of both cocaine dependence and major depression. All patients were treated at the Substance Treatment and Research Service, our outpatient substance abuse research facility in New York City. Seven had failed to improve during a prior 12-week randomized controlled trial of the antidepressant desipramine. One subject had stopped participation in the desipramine trial because of side effects (e.g., tiredness and dizziness) during 5 weeks of questionably compliant participation in the desipramine trial of 50 mg versus placebo. Another subject had been followed clinically while receiving relapse prevention treatment, but had not been randomly selected into the desipramine trial. The remaining four developed major depression during a 12-week trial of Pergolide for cocaine dependence. All subjects had been receiving relapse prevention therapy at least once per week and had failed to respond in terms of either mood or cocaine use for at least 8 weeks. All of the patients continued to meet DSM-III-R criteria for major depression and cocaine dependence, were in good physical health, did not meet criteria for any other Axis I disorder, and were not dependent on any other substance (excluding nicotine and caffeine). After giving informed consent, patients entered this 12-week open-label trial of venlafaxine approved by our Internal Review Board.

Patients attended the clinic once or twice per week and received individual relapse prevention therapy from a licensed clinical psychologist. The study psychiatrist met with the patients weekly to adjust dosage, administer the Hamilton Depression (HAM-D) scale biweekly, and complete a self-report log of substance abuse. Change in HAM-D scale scores and in cocaine use between baseline and follow-up points were evaluated with paired t tests.

Observed urines for toxicology were collected during the visits that occurred during regular clinic hours. All samples obtained were sent to the Central Reference Laboratory at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, were analyzed as positive/negative according to the standard cutoff of 300 ng/ml, and were used as an outcome measure.

RESULTS

Of the 13 patients, 11 completed the 12-week trial. One patient dropped out after the first dose of venlafaxine (37.5 mg) because of what she described as "dizziness and spaciness." She had no objective findings on her physical exam done at the time of the initial dosing and reported side effect, but chose to leave the trial. This was the same patient who had ended participation in the desipramine trial within 5 weeks of treatment and who had complained of similar symptoms after taking one daily dose of the trial medication (50 mg desipramine versus placebo; the blind has not been broken as that trial is ongoing). The other dropout had a substantial reduction in depressive symptoms during the first week of treatment, but continued to use cocaine on a daily basis, and after 2 weeks of treatment, entered an inpatient facility in another state. These two did not differ in any obvious way from the subjects who completed the study or from the patients who present to our outpatient facility in general. Data from the remaining 11 patients are presented.

Of the 11 treatment completers, 9 were males and 2 females. The majority were Caucasian (N = 9) and had a broad range of socioeconomic status. The average age was 37.4 [+ or -] 7.3 years with an age range of 28 to 52 years. As a group, the subjects were moderately to severely depressed, with an average total HAM-D score of 18.0 [+ or -] 3.0 at baseline. Their consumption of cocaine at baseline was cocaine worth $189 [+ or -] $78 per week and were using an average of 4.6 days per week (range 4-6 days per week) for the 3 weeks before beginning venlafaxine.

Venlafaxine was administered on a flexible schedule beginning with 37.5 mg twice daily and increased to 150 mg per day as tolerated. The median dose was 150 mg per day (75 mg twice a day), with a range of 37.5 mg to 225 mg. Depression and self-reported cocaine use outcome are presented in Table 1. Substantial reduction in HAM-D scores were observed at all follow-up points (Weeks 2, 6, and 12). By Week 2, a substantial ([is greater than] 75%) decrease in HAM-D scale scores was shown in 9 of 11 patients. Because the original protocol called for biweekly HAM-D ratings, there was no objective measure of depression at Week 1, although it was the treating clinician's impression that 8 of the 11 had improved in the first week. All 11 patients showed a decrease in depressive symptoms by Week 6 and an overall clinical improvement at Week 6, which was sustained at Week 12. Results are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Venlafaxine in the Treatment of Cocaine Dependence and Major Depression

(a) p < .001.

(b) p < .05.

Patients also reported significant reductions at each follow-up point in self-reported cocaine consumption compared to baseline. The urine results were consistent with self-reported cocaine use, and this is in keeping with our prior experience with the desipramine trial, as well as with previous experience with this population. Of 51 urines collected, 34 agreed with self-report (66.7%). Of the 17 that did not correspond, 3 were urine negative against self-reported use (5.9%), and 14 were positive against self-reported nonuse (27.5%). Thus, agreement between self-reported drug use and urine screens was reasonably high, supporting the use of self-reports, although there is some evidence of underreporting of cocaine use among patients reporting abstinence. The relatively small percentage of urines collected was a result of :missed visits and patients being seen outside regular clinical hours in the evening, when there was no mechanism to store the collected urine. This is a significant limitation of this study, which has resulted in mechanistic changes in our current protocols. None of the patients showed an elevation of blood pressure, and there were no reported serious side effects throughout the trial.

DISCUSSION

The results of this pilot study suggest, tentatively, that venlafaxine may be effective for the treatment of depression in cocaine-dependent patients, and that improvement in depression may be accompanied by a concomitant reduction in cocaine use. Antidepressants have not been successful in treating nondepressed samples of cocaine abusers, but further study of these agents may be warranted in patients with substantial depressive symptoms, as has been suggested by subgroup analysis of several previous CD trials (7, 12, 20).

Venlafaxine may be a good choice for a variety of reasons. Venlafaxine has a broad spectrum of action, inhibiting both norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake. It appears to have a relatively benign side effect profile, and our patients reported no significant side effects. Hypertension has been reported in a small population of depressed patients treated with venlafaxine (21), and this is a particular concern given the presser effects of cocaine. We are planning a laboratory-based human cocaine administration study with venlafaxine to investigate further the interaction between cocaine use and this medication. Furthermore, in at least one published report (22) and in our study, venlafaxine had an apparently rapid onset of clinical action. Rapid onset of action could be a distinct advantage by improving retention of outpatient cocaine abusers in treatment. The speed of onset of clinical improvement with antidepressant medication is a controversial and complex issue and may represent a placebo effect (19), so this issue can best be addressed in future placebo controlled trials.

There is a clear, but as yet incompletely defined, relationship between depression and drug dependence in general and cocaine dependence in particular (23). It may be argued that substance abusers with depressive symptoms that are either primary or chronic may contain a subset who, no matter what the true etiology of their symptoms, will benefit from treatment with antidepressant medications. This modest open-label trial adds to the growing body of evidence that, at least in the subpopulation of cocaine abusers with comorbidity (in particular, depression), pharmacotherapy may have a role in treatment.

Caution is warranted in evaluating the conclusions of this trial because of the small sample size and lack of suitable placebo control. The fact that depression had persisted through previous clinical trials involving other medications and relapse prevention makes spontaneous remission seem less likely. However, expectancy effects surrounding a new medication given in a nonblind fashion could have produced the observed results. Further, delayed effects of relapse prevention in reducing cocaine use have been demonstrated (5). All patients in this trial had already had several months of relapse prevention therapy before entering this trial.

Another important limitation is the lack of urine data on each of the patient visits. The reasonably good correspondence between the urines obtained and self-reports argues for validity of the self-reports, although there was some evidence of underreporting. It is also important to note that most patients reported reduced use rather than abstinence. Further studies should incorporate quantitative urine toxicology measures to try to measure reduced use as well as abstinence.

While there are certainly significant limitations to this modest trial, it does suggest that venlafaxine was well tolerated, and it may be that large-scale placebo-controlled trials of venlafaxine in depressed cocaine users are warranted. In the interim, venlafaxine might be considered for treatment-refractory cocaine abusers with substantial depression.

REFERENCES

(1) Gawin, F. H., and Kleber, H. D., Abstinence symptomatology and psychiatric diagnosis in cocaine abusers, Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 46:117-121 (1986).

(2.) Weiss, R. D., Mirin, S. M., Michael, J. L., et al., Psychopathology in chronic cocaine abusers, Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 12:17-29 (1986).

(3.) Nunes, E. V., Quitken, F. M., and Klein, D. F., Psychiatric diagnosis in cocaine abuse, Psychiatry Res. 28:105-114 (1989).

(4.) Carroll, K. M., Nich, C., and Rounsaville, B. J., Differential symptom reduction in depressed cocaine abusers treated with psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 183:251-259 (1995).

(5.) Carroll, K. M., Power, M. E., Bryant, K., et al., One-year follow-up status of treatment-seeking cocaine abusers. Psychopathology and dependence severity as predictors of outcome, J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 181:71-79 (1993).

(6.) American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., Author, Washington, DC, 1994.

(7.) Margolin, A., Kosten, T. R., Avants, S. K., et al., A multicenter trial of buproprion for cocaine dependence in methadone maintained patients, Drug Alcohol Depend. 40:125-131 (1995).

(8.) Nunes, E. V., Quitkin, F. M., Brady, R., et al., Antidepressant treatment in methadone maintenance patients, J. Addict. Dis. 13:13-24 (1994).

(9.) Zeidonis, D. M., and Kosten, T. R., Depression as a prognostic factor for pharmacological treatment of cocaine dependence, Psychopharmacol. Bull., 27:337-343 (1991).

(10.) Arndt, I. O., Dorozynsky, L., Woody, G. E., et al., Desipramine treatment of cocaine dependence in methadone-maintenance patients, Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 49:888-893 (1992).

(11.) Carroll, K. M., Rounsaville, B. J., Gordon, L. T., et al. Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for ambulatory cocaine abusers, Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 51:177-187 (1994).

(12.) Nunes, E. V., McGrath, P. J., Quitkin, F. M., et al., Imipramine treatment of cocaine abuse; possible boundaries of efficacy, Drug Alcohol Depend. 39:185-195 (1995).

(13.) Nunes, E. V., McGrath, P. J., Quitken, F. M., et al., Imipramine treatment of alcoholism with comorbid depression, Am. J. Psychiatry 150:963-965 (1993).

(14.) Mason, B. J., Kocsis J. H., Ritvo, E. C., et al., A double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of desipramine for primary alcohol dependence and stratified on the presence or absence of major depression, JAMA 275:761-767 (1996).

(15.) McGrath, P. J., Nunes, E. V., Stewart J. W., et al., Imipramine treatment of alcoholics with primary depression: a placebo-controlled clinical trial, Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 53:232-240 (1996).

(16.) Woody, G., McClellan, T., and Bedrick, J., Dual diagnosis, in Review of Psychiatry, Vol. 14 (J. M. Oldham and M. B. Riba, Eds.), APA Press, Washington, DC, 1995, pp. 83-103.

(17.) Nunes, E. V., Deliyannides, D., Donovan, S., et al., The management of treatment-resistance in depressed patients with substance use disorders, Psychiatric Clin. North Am. (1998).

(18.) Ellingrod, V. L., and Perry, P. J., Venlafaxine: a heterocyclic antidepressant, Am. J. Hosp. Pharmacol. 51:3033-3046 (1994).

(19.) Quitkin, F. M., McGrath, P. J., Stewart, J. W., et al., Can the effects of antidepressants be observed in the first two weeks of treatment? Neuropsychopharmacology 15(4):390-394 (1996).

(20.) Nunes, E. V., Methodologic recommendations for cocaine abuse clinical trials: a clinician-researcher's perspective, NIDA Res. Monogr. 175:73-95 (1997).

(21.) Augustin, B. G., Cold, J. A., and Jann, M. W., Venlafaxine and nefazodone, two pharmacologically distinct antidepressants, Pharmacotherapy 17(3):511-530 (1997).

(22.) Guelfi, J. D., White, C., Hackett, D., Effectiveness of venlafaxine in patients hospitalized for major depression and melancholia, J. Clin. Psychiatry 56:450-458 (1995).

(23.) Marcou, A., Kosten, T. R., and Koob, G. F., Neurobiological similarities in depression and drug dependence: a self-medication hypothesis, Neuropsychopharmacology 18:135-174 (1998).

McDowell, M.D.(*) Frances R. Levin, M.D. Angela M. Seracini, Ph.D. Edward V. Nunes, M.D.

New York State Psychiatric Institute Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons Department of Psychiatry Division on Substance Abuse Substance Treatment and Research Service (STARS) New York, New York

(*)To whom correspondence should be addressed at 600 West 168th Street, 2nd Floor, New York, NY 10032. Telephone: (212) 923-3031.

COPYRIGHT 2000 Marcel Dekker, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group