Milk thistle has been used as a cytoprotectant for the treatment of liver disease, for the treatment and prevention of cancer, and as a supportive treatment of Amanita phalloides poisoning. Clinical studies are largely heterogeneous and contradictory. Aside from mild gastrointestinal distress and allergic reactions, side effects are rare, and serious toxicity rarely has been reported. In an oral form standardized to contain 70 to 80 percent silymarin, milk thistle appears to be safe for up to 41 months of use. Significant drug reactions have not been reported. Clinical studies in oncology and infectious disease that are under way will help determine the efficacy and effectiveness of milk thistle. (Am Fam Physician 2005;72:1285-8. Copyright [c] 2005 American Academy of Family Physicians.)

**********

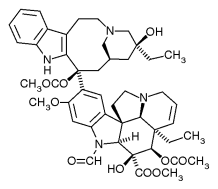

Milk thistle (Silybum marianum) was used in classical Greece to treat liver and gallbladder diseases and to protect the liver against toxins. It recently has been investigated for use as a cytoprotectant, an anticarcinogen, and a supportive treatment for liver damage from Amanita phalloides poisoning. Its active ingredient is silymarin, found primarily in the seeds. Silymarin undergoes enterohepatic recirculation, which results in higher concentrations in liver cells than in serum. (1) It is made up of components called flavonolignans, the most common being silybin. (2)

Pharmacology

A number of studies have suggested that silymarin is an anti-inflammatory. It regulates inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF), (3) TNF-alpha, (4) nitrous oxide, interleukin-6, and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. (5) Silymarin also increases lymphocyte proliferation, interferon gamma, interleukin-4, and interleukin-10 cytokines, in a dose-dependent manner. (6,7) Taken together, these effects suggest a possible role in preventing or treating infectious disease.

Several mechanisms of cytoprotection have been identified. In some studies, (8) milk thistle promoted neuronal differentiation and survival. In others, silymarin inhibited leukotriene formation by Kupffer cells (9) and increased expression of growth factor beta-1 and c-myc. (10) In animal studies, it has shown protective effects against damage to the pancreas from cyclosporine (Sandimmune) (11); damage to the kidney from acetaminophen, cisplatin (Platinol), and vincristine (Oncovin) (12); and damage to the liver from carbon tetrachloride, (13,14) partly by reducing lipid peroxidation. In another study, (15) silymarin slowed the progression of alcohol-induced liver fibrosis in baboons. In vitro and animal studies support the possibility that milk thistle has anticarcinogenic effects for cancers of the prostate, breast, skin, colon, tongue, and bladder. (16-24)

Uses and Effectiveness

LIVER DISEASE

In the United States, milk thistle is most commonly used to treat viral infections and cirrhosis of the liver. Clinical trials have produced conflicting results. In a study (25) of patients with cirrhosis, 170 patients (46 with alcoholism) were randomized to Legalon, a proprietary product standardized to contain 70 to 80 percent silymarin, or placebo. In the 146 patients who completed 24 to 41 months of therapy, there was a lower mortality rate among the patients treated with Legalon. The greatest benefit occurred in those whose cirrhosis was caused by alcoholism and in those who had less severe cirrhosis on entry. (25)

In a six-month double-blind study (26) of 36 patients with chronic alcoholic liver disease, the group given Legalon showed normalization of their bilirubin, aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase serum levels, and also showed improvement in histology. These effects did not occur in the placebo group. In another study, (27) 106 patients with mild acute and subacute liver disease characterized by elevated serum transaminase levels were randomized to receive silymarin or placebo. Of the 97 patients who completed the four-week study, there was a statistically significant greater decrease in transaminase levels in the silymarin group. In addition, results of a smaller study (28) of 20 patients with chronic active hepatitis randomized to placebo or silybin showed that the milk thistle group had significantly lower transaminase, bilirubin, and gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase levels than the placebo group. This study used a complex of silybin with phosphatidylcholine, which appears to increase bioavailability.

Other studies have not duplicated these positive effects. In a study (29) of 200 patients with alcoholic cirrhosis, there were no differences in time to death or progression to liver failure in the 125 patients who completed 24 months of therapy. Similarly, in a study (30) of 72 patients with alcoholic liver disease, there were no differences in mortality or laboratory values between the placebo and silymarin groups. Finally, a three-month study (31) of 116 patients with histologically proven alcoholic hepatitis randomized to placebo or silymarin showed no significant differences in serum transaminase activity or histologic fibrosis scores.

Two meta-analyses of milk thistle for liver disease (32,33) detail the major limitations of prior studies and conclude that data are insufficient to support its use at this time. The two main limitations are the heterogeneity of the study populations, caused by lack of precise inclusion and exclusion criteria and the noncomparability of doses received. Most studies did not report or use objective criteria to determine the severity and etiology of cirrhosis and did not control for confounding factors such as infection with hepatitis B or C and ongoing alcohol intake. In addition, the trials vary considerably in duration, ranging from one week to 41 months, without agreement on the minimum duration needed to see effect. The effect of silymarin is thought to be dose-dependent, and it is not known whether the bioavailability of different formulations is equivalent. (6,7) Because the studies used different products, it is not known whether participants in the different studies received equivalent doses. These limitations make comparisons of studies difficult to interpret. efforts are under way to isolate, semisynthesize, and extensively characterize the biologic activities of the flavonolignans that constitute silymarin. (34) Developing products that contain standardized percentages of precise ratios of the components of silymarin will improve the ability to test its effectiveness.

CYTOPROTECTANT

Studies of the use of milk thistle as a cytoprotectant in humans have been limited. In one study, (35) 49 of 200 workers exposed to toluene or xylene for five to 20 years developed persistent elevations in transaminase levels; 30 of these heterogeneous patients were treated with Legalon, whereas the others were not treated. In the Legalon group, transaminase activity decreased and platelet count increased when compared with the untreated group. Patients two to 21 years of age with acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are receiving hepatotoxic chemotherapy are being recruited for a second phase randomized pilot trial of silymarin.

ANTICARCINOGEN

Researchers are investigating the use of milk thistle's active ingredients for the prevention and treatment of cancer. Two additional animal studies on prostate cancer chemoprevention and treatment are ongoing, and a third phase trial in human prostate cancer patients with rising prostate-specific antigen also is under way.

AMANITA PHALLOIDES POISONING

The A. phalloides mushroom, called the "death cap," produces severe nausea, vomiting, and watery diarrhea within five to 12 hours of ingestion. This often causes hypovolemia and hypoglycemia. Silymarin inhibits the binding of the toxins in the mushroom to hepatocytes and interrupts the enterohepatic circulation of the toxins. (36) Several journals have published case reports of silymarin treatment (intravenously and orally) for A. phalloides poisoning in humans, but the largest series (37) followed only 18 patients. In every case, silymarin was used in combination with other agents, usually being added when standard treatment appeared to fail. The relative contribution of silymarin to these treatment regimens is unknown. The intravenous form of silymarin was used in these studies, but it is not available in the United States.

ADVERSE EFFECTS AND INTERACTIONS

The Agency for healthcare research and Quality reviewed the effects of milk thistle on liver disease and cirrhosis, (32) noting that serious adverse reactions are virtually unheard of. The most common reported complaints were gastrointestinal disturbances, but the overall incidence was no different from placebo. Allergic reactions, ranging from pruritus and rash to eczema and anaphylaxis, are rare.

Drug interactions do not appear to be problematic. Silybin inhibits the activities of CYP2D6, CYP2e1, and CYP3A4, but at physiologic concentrations far higher than those given clinically. (38) In a study (39) of 10 healthy volunteers, administration of 175 mg of milk thistle three times daily for three weeks had no significant effect on concomitantly administered indinavir (Crixivan).

DOSAGE

Most clinical trials have used daily dosages of 420 to 480 mg silymarin, divided into two or three doses daily. Until the specific effects of each of the flavonolignans is known and products are available that contain standardized ratios of these components, the optimal dosage will remain unknown. Table 1 outlines the efficacy, safety, tolerability, dosage, and cost of milk thistle.

Members of various family medicine departments develop articles for "Alternative and Complementary Medicine." This is one in a series coordinated by Sumi Sexton, M.D.

REFERENCES

(1.) Boerth J, Strong KM. The clinical utility of milk thistle (Silybum marianum) in cirrhosis of the liver. J Herb Pharmacother 2002;2:11-7.

(2.) Pepping J. Milk thistle: Silybum marianum. Am J Health Syst Pharm 1999;56:1195-7.

(3.) Manna SK, Mukhopadhyay A, Van NT, Aggarwal BB. Silymarin suppresses TNF-induced activation of NF-kappa B, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, and apoptosis. J Immunol 1999;163:6800-9.

(4.) Zi X, Mukhtar H, Agarwal R. Novel cancer chemopreventive effects of a flavonoid antioxidant silymarin: inhibition of mRNA expression of an endogenous tumor promoter TNF alpha. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997;239:334-9.

(5.) Tager M, Dietzmann J, Thiel U, Hinrich Neumann K, Ansorge S. Restoration of the cellular thiol status of peritoneal macrophages from CAPD patients by the flavonoids silibinin and silymarin. Free Radic Res 2001;34:137-51.

(6.) Wilasrusmee C, Kittur S, Shah G, Siddiqui J, Bruch D, Wilasrusmee S, et al. Immunostimulatory effect of Silybum marianum (milk thistle) extract. Med Sci Monit 2002;8:BR439-43.

(7.) Johnson VJ, Osuchowski MF, He Q, Sharma RP. Physiological responses to a natural antioxidant flavonoid mixture, silymarin, in BALB/c mice: II. Alterations in thymic differentiation correlate with changes in c-myc gene expression. Planta Med 2002;68:961-5.

(8.) Kittur S, Wilasrusmee S, Pedersen WA, Mattson MP, Straube-West K, Wilasrusmee C, et al. Neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects of milk thistle (Silybum marianum) on neurons in culture. J Mol Neurosci 2002;18:265-9.

(9.) Dehmlow C, Erhard J, de Groot H. Inhibition of Kupffer cell functions as an explanation for the hepatoprotective properties of silibinin. Hepatology 1996;23:749-54.

(10.) He Q, Osuchowski MF, Johnson VJ, Sharma RP. Physiological responses to a natural antioxidant flavonoid mixture, silymarin, in BALB/c mice: I. Induction of transforming growth factor beta1 and c-myc in liver with marginal effects on other genes. Planta Med 2002;68:676-9.

(11.) von Schonfeld J, Weisbrod B, Muller MK. Silibinin, a plant extract with antioxidant and membrane stabilizing properties, protects exocrine pancreas from cyclosporin A toxicity. Cell Mol Life Sci 1997;53:917-20.

(12.) Sonnenbichler J, Scalera F, Sonnenbichler I, Weyhenmeyer R. Stimulatory effects of silibinin and silicristin from the milk thistle Silybum marianum on kidney cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1999;290:1375-83.

(13.) Kravchenko LV, Avren'eva LI, Tutel'ian VA. Effects of bioflavonoids on the toxicity of T-toxin in rats. A biochemical study [Russian]. Vopr Pitan 2000;69:20-3.

(14.) Batakov EA. Effect of Silybum marianum oil and legalon on lipid peroxidation and liver antioxidant systems in rats intoxicated with carbon tetrachloride [Russian]. Eksp Klin Farmakol 2001;64:53-5.

(15.) Lieber CS, Leo MA, Cao Q, Ren C, DeCarli LM. Silymarin retards the progression of alcohol-induced hepatic fibrosis in baboons. J Clin Gastroenterol 2003;37:336-9.

(16.) Tyagi AK, Singh RP, Agarwal C, Chan DC, Agarwal R. Silibinin strongly synergizes human prostate carcinoma DU145 cells to doxorubicininduced growth inhibition, G2-M arrest, and apoptosis. Clin Cancer Res 2002;8:3512-9.

(17.) Singh RP, Dhanalakshmi S, Tyagi AK, Chan DC, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Dietary feeding of silibinin inhibits advance human prostate carcinoma growth in athymic nude mice and increases plasma insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 levels. Cancer Res 2002;62:3063-9.

(18.) Zi X, Feyes DK, Agarwal R. Anticarcinogenic effect of a flavonoid antioxidant, silymarin, in human breast cancer cells MDA-MB 468: induction of G1 arrest through an increase in Cip1/p21 concomitant with a decrease in kinase activity of cyclin-dependent kinases and associated cyclins. Clin Cancer Res 1998;4:1055-64.

(19.) Katiyar SK. Treatment of silymarin, a plant flavonoid, prevents ultraviolet light-induced immune suppression and oxidative stress in mouse skin. Int J Oncol 2002;21:1213-22.

(20.) Katiyar SK, Korman NJ, Mukhtar H, Agarwal R. Protective effects of silymarin against photocarcinogenesis in a mouse skin model. J Natl Cancer Inst 1997;89:556-66.

(21.) Lahiri-Chatterjee M, Katiyar SK, Mohan RR, Agarwal R. A flavonoid antioxidant, silymarin, affords exceptionally high protection against tumor promotion in the SENCAR mouse skin tumorigenesis model. Cancer Res 1999;59:622-32.

(22.) Kohno H, Tanaka T, Kawabata K, Hirose Y, Sugie S, Tsuda H, et al. Silymarin, a naturally occurring polyphenolic antioxidant flavonoid, inhibits azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in male F344 rats. Int J Cancer 2002;101:461-8.

(23.) Yanaida Y, Kohno H, Yoshida K, Hirose Y, Yamada Y, Mori H, et al. Dietary silymarin suppresses 4-nitroquinoline 1-oxide-induced tongue carcinogenesis in male F344 rats. Carcinogenesis 2002;23:787-94.

(24.) Vinh PQ, Sugie S, Tanaka T, Hara A, Yamada Y, Katayama M, et al. Chemopreventive effects of a flavonoid antioxidant silymarin on N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl) nitrosamine-induced urinary bladder carcinogenesis in male ICR mice. Jpn J Cancer Res 2002;93:42-9.

(25.) Ferenci P, Dragosics B, Dittrich H, Frank H, Benda L, Lochs H, et al. Randomized controlled trial of silymarin treatment in patients with cirrhosis of the liver. J Hepatol 1989;9:105-13.

(26.) Feher J, Deak G, Muzes G, Lang I, Niederland V, Nekam K, et al. Liverprotective action of silymarin therapy in chronic alcoholic liver diseases [Hungarian]. Orv Hetil 1989;130:2723-7.

(27.) Salmi HA, Sarna S. Effect of silymarin on chemical, functional, and morphological alterations of the liver. A double-blind controlled study. Scan J Gastroenterol 1982;17:517-21.

(28.) Pares A, Planas R, Torres M, Caballeria J, Viver JM, Acero D, et al. Effects of silymarin in alcoholic patients with cirrhosis of the liver: results of a controlled, double-blind, randomized and multicenter trial. J Hepatol 1998;28:615-21.

(29.) Buzzelli G, Moscarella S, Giusti A, Duchini A, Marena C, Lampertico M. A pilot study on the liver protective effect of silybin-phosphatidylcholine complex (IdB1016) in chronic active hepatitis. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol 1993;31:456-60.

(30.) Bunout D, Hirsch S, Petermann M, de la Maza MP, Silva G, Kelly M, et al. Controlled study of the effect of silymarin on alcoholic liver disease [Spanish]. Rev Med Chil 1992;120:1370-5.

(31.) Trinchet JC, Coste T, Levy VG, Vivet F, Duchatelle V, Legendre C, et al. Treatment of alcoholic hepatitis with silymarin. A double-blind comparative study in 116 patients [French]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1989;13:120-4.

(32.) Mulrow C, Lawrence V, Jacobs B, Dennehy C, Sapp J, Ramirez G, et al. Milk thistle: effects on liver disease and cirrhosis and clinical adverse effects. Evid Rep Technol Assess [Summary] 2000;21:1-3.

(33.) Jacobs BP, Dennehy C, Ramirez G, Sapp J, Lawrence VA. Milk thistle for the treatment of liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med 2002;113:506-15.

(34.) Lee DY, Liu Y. Molecular structure and stereochemistry of silybin A, silybin B, isosilybin A, and isosilybin B, isolated from Silybum marianum (milk thistle) [published correction appears in J Nat Prod 2003;66:1632]. J Nat Prod 2003;66:1171-4.

(35.) Szilard S, Szentgyorgyi D, Demeter I. Protective effect of Legalon in workers exposed to organic solvents. Acta Med Hung 1998;45:249-56.

(36.) Ford MD. Clinical toxicology. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2001.

(37.) Hruby K, Csomos G, Fuhrmann M, Thaler H. Chemotherapy of Amanita phalloides poisoning with intravenous silibinin. Hum Toxicol 1983;2:183-95.

(38.) Zuber R, Modriansky M, Dvorak Z, Rohovsky P, Ulrichova J, Simanek V, et al. Effect of silybin and its congeners on human liver microsomal cytochrome P450 activities. Phytother Res 2002;16:632-8.

(39.) Piscitelli SC, Formentini E, Burstein AH, Alfaro R, Jagannatha S, Falloon J. Effect of milk thistle on the pharmacokinetics of indinavir in healthy volunteers. Pharmacotherapy 2002;22:551-6.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

FRANCINE RAINONE, D.O., PH.D., M.S., is assistant professor of family medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University, Bronx, N.Y., where she teaches in the Montefiore Medical Center Residency Program in social medicine. Dr. Rainone also is the program director of the Palliative Care Suite at Montefiore and the program director of the Fellowship in Palliative Care.

Address correspondence to Francine Rainone, D.O., PH.D., M.S., Montefiore Medical Center, Department of Family Medicine, 3544 Jerome Ave., Bronx, NY 10467 (e-mail: frainone@montefiore.org). Reprints are not available from the author.

COPYRIGHT 2005 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group