Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a prevalent pathogen, with 40 to 100 percent of the general population showing prior exposure by serology. (1) Up to 20 percent of children in the United States will have contracted CMV before puberty. Children may in turn be reinfected with different strains of the virus. (2) Infection also is common during adolescence, which directly corresponds to the start of sexual activity.

CMV is a member of the Herpesviridae family, which includes the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), herpes simplex virus, varicella-zoster virus, and herpesvirus 6, 7, and 8.

Primary infection is usually inapparent. As with other herpes viruses, CMV remains latent within the host, reactivating and shedding when the host's immune system is compromised.

CMV is not highly contagious. It is contracted from close personal contact with people who excrete the virus in their body fluids (e.g., saliva, urine, blood, breast milk, semen, and even transplanted organ tissue). It also can be shed from the throat and uterine cervix.

Initial infection in newborns and reactivation of the virus in immunocompromised persons can result in severe pathology. CMV also is a serious pathogen in patients who have received an organ transplant.

Day care workers are at increased risk of acute CMV infection, especially those who work with children under two years of age. (2,3) In this setting, CMV is most likely spread through close contact with infected children and subsequent, inadequate handwashing. (4) The higher rates of acute CMV infection among adolescents and day care workers are of concern because of the resultant congenital infection in women who contract primary CMV while pregnant. Health care workers who treat patients with known, active CMV infection seem to be at no greater risk of contracting CMV than the general population. (5)

Family physicians are most likely to encounter CMV during the work-up of patients presenting with an infectious mononucleosis syndrome, acute hepatitis, or as an opportunistic infection in persons with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

CMV Infection

A typical mononucleosis syndrome consists of an acute febrile illness with an increase of 50 percent or more in the number of lymphocytes or monocytes, with at least 10 percent of the lymphocytes being atypical. Five to 7 percent of immunocompetent patients with this syndrome who present to a physician's office will have acute CMV infection. (6) CMV-induced mononucleosis can be symptomatically indistinguishable from EBV-induced mononucleosis. (7) Malaise, fever up to 39.4[degrees]C (103.0[degrees]F), chills, sore throat, headache, and fatigue can be the predominant features of both viruses. Many of the same clinical manifestations typical of EBV-induced mononucleosis (e.g., lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, pharyngeal erythema) also can occur with CMV (Table 1), although less frequently. (8)

Patients with mononucleosis may present with nonspecific skin rashes (e.g., generalized maculopapular, urticarial, and scarlatiniform rashes). (9) These rashes are not a direct cause of CMV proliferation within the skin but are the result of an immunologic response to the virus. (10) The classic hypersensitivity drug rash associated with ampicillin therapy given to patients with EBV-induced mononucleosis also can occur in CMV-induced mononucleosis.

Elevation of liver transaminase levels is a common feature of acute CMV infection, occurring in up to 92 percent of patients, and often it can be mistaken for acute hepatitis. In contrast to other viral causes of hepatitis, patients with CMV are anicteric, and their aspartate transaminase and alanine transaminase levels rarely go above five times their normal ranges. (11) Other laboratory abnormalities found in association with acute CMV infection include anemia, thrombocytopenia, and positive cold agglutinins. (12)

Guillain-Barre syndrome related to CMV has been documented, as have the much less frequent complications of encephalitis, myocarditis, or fulminant hepatitis. (13) These severe complications rarely appear in immunocompetent persons. As of 1996, only 34 cases of severe organ involvement of the brain, heart, liver, or lungs have been documented. (14)

Diagnosis

Any febrile illness in which more than 10 percent of the patient's lymphocytes are atypical should raise the suspicion of mononucleosis. Though EBV will be the causative agent in the majority of cases, the differential diagnosis includes CMV, toxoplasmosis, acute viral hepatitis, human herpesvirus 6, and drug reaction. (15) Acute HIV infection also may present as a mononucleosis-like syndrome, but HIV-infected patients lack the atypical lymphocytosis.

The possibility of acute CMV infection should be explored if a negative heterophil antibody test rules out EBV mononucleosis. CMV infection, serum sickness, or another viral illness rarely causes a false-positive heterophil antibody test. The best diagnostic test for establishing CMV mononucleosis is serology for CMV IgM antibodies, which should be positive in the majority of patients during the symptomatic phase of the illness. However, antibodies may not peak until four to seven weeks into the infectious process. In contrast to many other viral illnesses, the IgM antibodies produced in response to acute CMV infection may remain elevated for up to one year or longer following acute infection in up to 20 percent of patients. This may make it confusing to rule out CMV infection as the cause of a fever. In infected patients, the level of IgG antibodies to CMV should continue to increase at least fourfold during acute infection. Therefore, monitoring the IgG antibody level is the best method to determine that CMV is the cause of fever in these cases.

CMV IgM tests typically cost between $66 and $98. Thus, it may not be prudent to order an entire panel of serologies at once in patients presenting with mononucleosis symptoms. A cost-effective testing algorithm was developed for managing these patients who are heterophil-negative (Figure 1). (15) Patients who were Monospot-negative were categorized into those with or without an absolute lymphocytosis or greater than 10 percent atypical lymphocytes. EBV IgM testing was ordered on those with positive parameters; testing for CMV IgM was ordered if the EBV IgM was negative. Knowing that a patient's symptoms are secondary to acute CMV infection can therefore preclude further costly work-up.

[FIGURE 1 OMITTED]

Laboratory tests that may be rendered falsely positive from acute CMV infection include rheumatoid factor, positive direct Coombs', polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia, cryoglobulinemia, and a transient positive antinuclear antibody (speckled pattern). CMV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or culture is not useful in the diagnosis of primary CMV infection, because a positive test may just reflect viral shedding via a transient reactivation from the latent state. High quantities of circulating CMV by PCR in the immunocompromised patient may forebode the onset of end-organ involvement by CMV, and a positive PCR test in cerebral spinal fluid is of use in the diagnosis of CMV encephalitis or polyradiculopathy. Histologically, the detection of the distinct "owl's eye" inclusion bodies on tissue sample can be a highly specific method for determining organ involvement of CMV (Figure 2).16

[FIGURE 2 OMITTED]

Infection Control

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) does not recommend withdrawing children with known CMV infection from day care, because CMV is nearly universally present. Health care workers with known CMV infection need not be restricted from work, because strict handwashing and education about standard precautions can control transmission of CMV. (17)

Serologic or virologic screening programs to detect CMV in women of childbearing potential are not practical or cost-effective, because seropositive status does not predict reactivation of latent infection or reinfection with a new strain of CMV. (17) Restrictions on breastfeeding also are not made, because the benefits of breast milk appear to outweigh the small risk of the child acquiring CMV from the mother.

Patients with HIV

The second most common context in which a family physician will encounter the clinical sequelae of CMV infection is in patients with HIV who have a CD4 T-lymphocyte count of less than 50 per mm3 (50 3 106 per L). In the era before highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), CMV was the most common viral opportunistic infection in HIV patients.

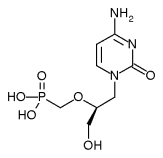

CMV-induced end-organ damage, mostly in the form of retinitis, manifested in 21 to 45 percent of such patients.(18) A patient with HIV may present with a diverse variety of visual complaints secondary to CMV retinitis, including painless blurred vision, unilateral floaters, light flashes, scotoma, or the loss of central vision, depending on the location and extent of the retinal lesion. (19-21) The retinitis caused by CMV is a focal necrotizing type, with or without hemorrhages (Figure 3). The destruction of the retina, which causes irreversible blindness, can be arrested and suppressed by anti-CMV agents. These medications halt CMV replication but do not eliminate the virus. The natural course of untreated CMV retinitis results in disease progression within approximately two weeks. Before HAART, therapy would only delay the progression of retinitis by two months in most patients treated with intravenous anti-CMV medications. For those treated with intravitreous ganciclovir implants, the progress of the disease could be delayed by seven months. Intraocular ganciclovir implants should be accompanied by oral ganciclovir (Cytovene), 1 g orally three times per day, to prevent CMV retinitis in the contralateral eye. For intravenous administration, intravitreous ganciclovir, 5 mg per kg every 12 hours, should be given for 14 to 21 days. Other options include intravenous cidofovir (Vistide), 5 mg per kg once weekly for two weeks, then 5 mg per kg every other week, or intravenous foscarnet (Foscavir). (22)

[FIGURE 3 OMITTED]

A recent study (23) comparing use of ganciclovir implants plus oral ganciclovir versus parenteral cidofovir after HAART revealed no differences between the regimens in terms of general health or vision measures. The rate of vitreous hemorrhage and neutropenia was higher in the ganciclovir group, with higher levels of uveitis and nephrotoxicity seen in patients in the cidofovir arm of the study. Valganciclovir (Valcyte) is the oral pro-drug of ganciclovir, and has efficacy comparable to intravenous ganciclovir. Its side effect profile is similar to that of intravenous ganciclovir, but it cannot be substituted for oral ganciclovir capsules on a one-to-one basis.

HAART is the cornerstone of therapy for preventing recurrent retinitis. (21) HAART can increase a patient's CD4 count and decrease the replicative abilities of CMV. The immunorestoration and protective benefits provided by HAART may cause pro-inflammatory complications, such as vitreitis and cystoid macular edema, which develop from an enhanced T-lymphocyte response to CMV. (19,21) If a patient's retinitis remains stable with anti-CMV therapy and HAART restores the CD4 count to above 100 per [mm.sup.3] (100 3 [10.sup.6] per L) for a three- to six-month period, then it may be possible to stop anti-CMV therapy.21 This should only be done with close monitoring by an ophthalmologist and the realization that anti-CMV therapy may need to be re-initiated if the patient's CD4 count drops again. Fortunately, the incidence of CMV retinitis has decreased significantly in response to HAART. (24)

Patients who have HIV infection should be asked by their physician at each visit about their visual symptoms. An ophthalmologist should do a dilated indirect funduscopic examination on patients with symptoms or a CD4 count of less than 50 per [mm.sup.3] every three to four months. Because only 10 percent of the retinal area can be observed with the use of a direct ophthalmoscope, it is not recommended as a diagnostic or evaluating tool. (20)

Extraocular Complications

The dermatologic manifestations of CMV infection may differ in patients with HIV infection. Patients with CMV infection of the skin may present with nonspecific rashes, perifollicular papulopustules, vesiculobullous eruptions, and nodular or ulcerative lesions. (9)

Patients with HIV who have low CD4 counts may experience complications from CMV involvement of the esophagus, colon, mucous membranes (ulcerative lesions and colitis), brain (meningoencephalitis), peripheral nerves (radiculopathy and myelopathy), and lungs (interstitial pneumonia). Primary prophylaxis against CMV in those patients with low CD4 counts and positive CMV PCR by oral ganciclovir is of questionable value. (25) HAART appears to be the best method to prevent CMV in patients with CD4 counts of less than 50 per [mm.sup.3]. (24)

Transplant Patients

CMV is a problematic infection in many transplant patients. Seronegative patients can acquire the infection from organ donors. CMV-related disease processes manifest differently depending on which organ is transplanted. In bone marrow recipients, CMV infection occurs as an interstitial pneumonia with high mortality. In liver recipients, hepatitis can be problematic and may be difficult to discern from organ rejection. The presentation of "CMV syndrome" (consisting of fever, leukopenia, atypical lymphocytes, hepatomegaly, myalgia, and arthralgia) is the most common manifestation of primary CMV in kidney transplant patients. (26)

The author thanks Juanita Hines for her assistance with the preparation of the manuscript.

The author indicates that he does not have any conflicts of interest. Sources of funding: none reported.

REFERENCES

(1.) de Jong MD, Galasso GJ, Gazzard B, Griffiths PD, Jabs DA, Kern ER, Spector SA. Summary of the II International Symposium on Cytomegalovirus. Antiviral Res 1998;39:141-62.

(2.) Bale JF Jr., Petheram SJ, Souza IE, Murph JR. Cytomegalovirus reinfection in young children. J Pediatr 1996;128:347-52.

(3.) Adler SP. Cytomegalovirus and child day care. Evidence for an increased infection rate among day-care workers. N Engl J Med 1989;321:1290-6.

(4.) Bale JF Jr., Zimmerman B, Dawson JD, Souza IE, Petheram SJ, Murph JR. Cytomegalovirus transmission in child care homes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153:75-9.

(5.) Balcarek KB, Bagley R, Cloud GA, Pass RF. Cytomegalovirus infection among employees of a children's hospital. No evidence for increased risk associated with patient care. JAMA 1990;263:840-4.

(6.) Evans AS. Infectious mononucleosis and related syndromes. Am J Med Sci 1978;276:325-39.

(7.) Klemola E, Kaariainen L. Cytomegalovirus as a possible cause of a disease resembling infectious mononucleosis. Br Med J 1965;5470:1099-102.

(8.) Jordan MC, Rousseau W, Stewart JA, Noble GR, Chin TD. Spontaneous cytomegalovirus mononucleosis. Ann Intern Med 1973;79:153-60.

(9.) Drago F, Aragone MG, Lugani C, Rebora A. Cytomegalovirus infection in normal and immunocompromised humans. A review. Dermatology 2000;200:189-95.

(10.) Kano Y, Shiohara T. Current understanding of cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent individuals. J Dermatol Sci 2000;22:196-204.

(11.) Horwitz CA, Henle W, Henle G. Diagnostic aspects of the cytomegalovirus mononucleosis syndrome in previously healthy persons. Postgrad Med 1979;66:153-8.

(12.) Wright JG. Severe thrombocytopenia secondary to asymptomatic cytomegalovirus infection in an immunocompetent host. J Clin Pathol 1992;45: 1037-8.

(13.) Phillips CA, Fanning WL, Gump DW, Phillips CF. Cytomegalovirus encephalitis in immunologically normal adults. Successful treatment with vidarabine. JAMA 1977;238:2299-300.

(14.) Eddleston M, Peacock S, Juniper M, Warrell DA. Severe cytomegalovirus infection in immunocompetent patients. Clin Infect Dis 1997;24:52-6.

(15.) Tsaparas YF, Brigden ML, Mathias R, Thomas E, Raboud J, Doyle P. Proportion positive for Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, human herpesvirus 6, Toxoplasma, and human immunodeficiency virus types 1 and 2 in heterophile-negative patients with an absolute lymphocytosis or an instrument-generated atypical lymphocyte flag. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2000;124:1324-30.

(16.) Mattes FM, McLaughlin JE, Emery VC, Clark DA, Griffiths PD. Histopathological detection of owl's eye inclusions is still specific for cytomegalovirus in the era of human herpesviruses 6 and 7. J Clin Pathol 2000;53:612-4.

(17.) Bolyard EA, Tablan OC, Williams WW, Pearson ML, Shapiro CN, Deitchmann SD. Guideline for infection control in healthcare personnel, 1998. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 1998;19:407-63.

(18.) Hoover DR, Saah AJ, Bacellar H, Phair J, Detels R, Anderson R, et al. Clinical manifestations of AIDS in the era of Pneumocystis prophylaxis. N Engl J Med 1993;329:1922-6.

(19.) Deayton JR, Wilson P, Sabin CA, Davey CC, Johnson MA, Emery VC, et al. Changes in the natural history of cytomegalovirus retinitis following the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2000;14:1163-70.

(20.) Holland G, Tufail A, Jordon M. Cytomegalovirus diseases. In: Pepose JS, Holland GN, Wilhelmus KR, eds. Ocular infection & immunity. St. Louis: Mosby, 1996:1088.

(21.) Whitcup SM. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. JAMA 2000; 283:653-7.

(22.) Dolin R, Masur H, Saag MS. AIDS therapy. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 1999.

(23.) The ganciclovir implant plus oral ganciclovir versus parenteral cidofovir for the treatment of cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: The Ganciclovir Cidofovir Cytomegalovirus Retinitis Trial. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;131:457-67.

(24.) O'Sullivan CE, Drew, WL, McMullen DJ, Miner R, Lee JY, Kaslow RA, et al. Decrease of cytomegalovirus replication in human immunodeficiency virus infected-patients after treatment with highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 1999;180:847-9.

(25.) Brosgart CL, Louis TA, Hillman DW, Craig CP, Alston B, Fisher E, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the safety and efficacy of oral ganciclovir for prophylaxis of cytomegalovirus disease in HIV-infected individuals. AIDS 1998;12:269-77.

(26.) Mandell GL, Douglas RG, Bennett JE. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and practice of infectious diseases. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

GREGORY H. TAYLOR, M.D., is an assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, and clinical faculty at the Institute of Human Virology, Baltimore. Dr. Taylor earned his medical degree from the University of Maryland School of Medicine where he also completed a residency in family medicine.

Address correspondence to Gregory H. Taylor, M.D., University of Maryland, 29 S. Greene St., Suite 300, Baltimore, MD 21201 (e-mail: gtaylor@umaryland.edu). Reprints are not available from the author.

COPYRIGHT 2003 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group