One of the most devastating epidemics in human history began with little fanfare in 1981 when the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention quietly released a nine-paragraph report detailing five cases of an unusual disease in gay men.

The disease in the report, which came to be known as AIDS, soon would grab headlines nationwide. In the years since, it's never let go. Shortly after the report's release, doctors and scientists worldwide rapidly realized they were up against a new and little-understood viral foe with an almost sinister ability to outwit that most powerful of disease fighters--the human immune system. In turn, public fears mounted as news reports detailed the lack of medical weapons with which to assault this new, frightening disease and its potential to spread to those previously not thought to be at risk.

In the past two decades, many of these fears have been realized. AIDS has indeed become a 21st century plague. Fifty-eight million people worldwide have been infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, according to the Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS. Twenty-two million have died after the virus rendered their immune system nearly defenseless, leaving them open to some types of cancer, nerve degeneration and opportunistic infections such as tuberculosis and pneumonia that physicians once thought were under control.

Over the past 20 years, AIDS has become a part of life everywhere on the planet. Few people have been unaffected by its tragic toll, and it remains one of the most feared of all infections. That's not likely to change as the third decade of AIDS begins. Despite medical advances, a cure is elusive. AIDS is a serious, difficult-to-treat and ultimately fatal disease, though the outlook for those living with it has steadily improved in the United States as new drugs have gained approval from the Food and Drug Administration.

Twenty years of public discussion about AIDS has also yielded slow progress in the ongoing debate about how to fight the disease and care for those who have it. Today, the financial, political and social issues that stem from AIDS are discussed as much as its symptoms, and those issues grow more complex each year.

Simply put, "AIDS remains a challenge for us all," says Keith Henry, M.D., an internationally known researcher and clinician at the University of Minnesota and Hennepin County Medical Center in Minneapolis.

Understanding the Virus

Although AIDS was first recognized in 1981, HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus that causes AIDS, was not identified until 1983. Since then, researchers have been studying how the virus attacks and replicates itself inside cells of the immune system.

HIV is a virus--essentially a submicroscopic parasite consisting of a core of RNA wrapped in a protein coat--that cannot replicate without invading living cells. At its most basic, a virus takes over the cell's mission control center to make the cell do HIV's bidding instead of functioning normally. Viruses responsible for influenza and the common cold operate similarly. However, while cold and flu viruses can make people miserable for a time, in healthy people they are usually defeated handily by the immune system.

HIV is different. It directly attacks the cells of the immune system, the body's defense system. Specifically, HIV goes after a type of immune cell called the CD4 lymphocyte. CD4 cells play a crucial role in the immune system because they coordinate the attack by white blood cells and antibodies on viruses and other body invaders.

HIV has a stealthy ability to escape detection as an enemy by CD4 cells. It then attaches to these cells and enters them. Once inside, the virus's genetic material takes command of the CD4 cell and forces it to make copies of the virus. (See "Simplified HIV Life Cycle," page 30.)

New copies of the virus burst forth from the cell, which then dies, and go in search of other cells to invade. The cycle continues again and again, with up to 10 billion new HIV virus particles produced every day by the commandeered cells. About 2 billion new CD4 cells are needed each day if this process is to be kept in check.

But the body can't keep up. In fact, the number of CD4 cells drops off sharply as HIV's foothold in the body strengthens. The body becomes unable to protect itself not only from HIV, but also from other viruses, bacteria, fungi and parasites. This is when someone infected with HIV develops Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, or AIDS.

Battling the Virus

These unique abilities of HIV have made the medical fight against it extremely challenging. Scientists and physicians hadn't seen anything like the virus before, and in the early 1980s there were no drugs to treat it. There also were few measures to combat the opportunistic infections that invaded the bodies of people whose immune systems had been decimated by HIV.

Prevention is the most effective weapon against HIV and AIDS. During the 1980s, gay rights organizations and public health professionals spearheaded campaigns to provide those most at risk for sexual transmission of the disease with some straightforward advice on how to prevent it--namely, the use of condoms.

Information aimed at intravenous drug users, who can acquire the virus by sharing needles with someone who is infected with HIV, also became available. The campaigns were often controversial, but AIDS researchers believe that they were effective, and helped to slow the spread of the disease both within at-risk communities and outside them.

"The message seemed to get through," says Tim Schacker, M.D., an AIDS

researcher and clinician at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

AIDS advocacy organizations, now part of the landscape in every large city and a fixture during lobbying time at the state and federal level, also came into being. Their purpose was to seek support and money for prevention campaigns and also to direct public funds towards finding a cure.

"Education led to advocacy, that led to meetings with the FDA," said Martin Delaney, founding director of the AIDS advocacy group Project Inform in San Francisco.

A corner seemed to be turned in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Public hysteria over the new virus began to recede. At the same time, prevention and lobbying campaigns matured, and medical research began bearing fruit in the form of new drugs.

The Golden Era

Despite their complex workings and complicated names, AIDS drugs are based on a relatively straightforward concept. By stopping or retarding the duplication of HIV inside the body's cells, the virus is prevented from overwhelming the immune system as it does when left unchecked. Researchers creating early HIV medicines followed this concept, and current medication has built on the theory.

The first drug to treat AIDS, the well-known AZT (zidovudine), was approved by the FDA in the United States in 1987. Initially created as a potential treatment for cancer, AZT was heralded as a wonder drug. Given the time and circumstances, it's understandable why. AZT was the first drug to show true promise in keeping the virus in check.

Consequently, AIDS patients and advocates began to demand access to the drug even while it was still in clinical trials. To accommodate patients' needs, the FDA streamlined the approval process to help get the drug to those who needed it while still ensuring its safety.

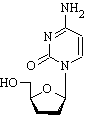

AZT belongs to a group of AIDS drugs known as nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), which was the first group of drugs developed to fight the virus. These drugs work by interfering with an enzyme called reverse transcriptase that the virus needs to integrate itself into a human cell. In addition to AZT (Retrovir, zidovudine), NRTI drugs include Epivir (lamivudine, 3TC), Videx (didanosine, ddI), Hivid (zalcitabine, ddC), Zerit (stavudine, d4t), and one of the newest drugs on the market, Ziagen (abacavir).

However, AZT and the other NRTIs were no cure. While they seemed to lower the amount of virus in the blood--called the viral load--for a time or keep it in check, they didn't eradicate the virus from the body completely. Another troubling finding: AZT, which had held so much promise, began to lose its effectiveness as the virus began to change to overcome the drug's effect. Though inroads were being made, researchers knew there was still a long battle ahead.

"It was getting better, but people were still dying," says Jeffrey S. Murray, M.D., M.P.H., a veteran FDA researcher and clinician in the fight against AIDS. More weapons against HIV were needed. Gradually, the medical arsenal expanded.

A major addition has been the protease inhibitors, which became widely available in 1995. Protease inhibitors include Crixivan (indinavir), Norvir (ritonavir), Viracept (nelfinavir), Fortovase (saquinavir), and Agenerase (amprenavir). Like NRTIs, these drugs interfere with the virus's ability to replicate in the body and inhibit the action of another key enzyme (protease). This enzyme is responsible for breaking apart large HIV proteins within the virus into smaller ones.

Another group of drugs to treat AIDS is the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, or NNRTIs. Like AZT and other NRTIs, these drugs also interfere with the reverse transcriptase enzyme to prevent HIV from replicating in the body. NNRTI drugs include Viramune (nevirapine), Sustiva (efavirenz) and Rescriptor (delavirdine).

Combination `Cocktails'

None of these drugs proved to be a solution in and of themselves, particularly as the virus would again mutate to overcome the drug's effects. However, scientists began to realize that the drugs together packed a powerful punch against the virus. In 1995, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) showed that combining these drugs slows the high rate of mutation, a characteristic of HIV.

The drug combinations became known as cocktails, a breezy name for a major advance in the battle against HIV. A new treatment era was born, accompanied by previously unknown levels of optimism.

Between 1996 and 1997, the number of AIDS-related deaths dropped 42 percent. Another decline, this time of 20 percent, followed between 1997 and 1998. In a report released by the Kaiser Family Foundation, AIDS-related deaths numbered 44,991 in 1993. Just five years later, the toll had dropped to only 17,171.

"That was the golden age," says the FDA's Murray.

It was at this time when Ken Eppich of Minneapolis, then 53, was told he was HIV-positive.

Eppich, who is gay, clearly remembers the sunny fall day in 1994 when he learned his diagnosis. Equally clear in his memory is the almost instant acceptance of his fate. Eppich believed that he would die soon, like so many of the friends and colleagues he had known with the disease.

"I thought I had 18 months to live," Eppich says.

Eppich set about making a will and making peace with himself. "I was OK with it. I'd had a good life."

Eppich's experience, however, epitomizes the changing expectations for AIDS patients brought on by this golden era. Having first learned of AIDS in the 1980s, he and his friends and family viewed AIDS as a death sentence.

"I never asked for a prognosis and my doctor wisely didn't offer one. My friends were sure I was dying and my brother felt that the Thanksgiving of 1994 would be my last," Eppich says.

Instead, he was given a bunch of drugs he'd never heard of. He took them, he read up on them--to the point that his doctor joked that the patient was the one really prescribing the medications--and made major changes in his life to stay healthy. And he lived.

Seven years later, in September 2001, Eppich found himself at a cabin in northern Minnesota on another clear, fall day with friends. They hoisted a toast to him and to his life.

"(AIDS) is a part of me, but it doesn't define or control me," says Eppich. "I think of it as a manageable, chronic illness rather than a fatal disease."

Reality Check

Like Eppich, AIDS patients, today, can plan for their futures. But the optimism brought by the new drugs of the 1990s has dimmed as doctors and their patients have realized that the virus won't be vanquished so easily. Nor have the societal issues raised by the disease gone away.

The cocktails, the source of so much hope, have become less effective. As HIV replicates in the body, it is able to change ever so slightly. These changes have allowed it to steel itself against new drug enemies. Changing cocktail combinations has helped curb resistance, but researchers say there just aren't enough drugs or combinations to stay ahead of the constantly mutating virus.

"It isn't even a question of when we're going to start losing people," says Murray. "We already have because we have run out of new effective drugs to try."

New drugs are currently in the pipeline and moving ahead at a rapid pace, according to Murray. Research on potential AIDS vaccines is underway, but progress has been slower. In fact, some have referred to the vaccine pipeline as a "pipette." Since 1987, more than 40 different AIDS vaccines have been tested on a limited basis. Only one, AIDSVAX, has been thought promising enough to merit testing in humans in a large-scale study. Much of the research is being done in Thailand, though some of the work is also underway in the United States.

As the drug arsenal has expanded, so too has the debate about the disease, both within the medical community and outside it. In fact, the drugs that spawned the "golden era" of AIDS treatment have usually been at the heart of the discussion.

One major issue is that the drugs are expensive. Treatment for HIV and AIDS patients cost the United States government $6.9 billion in fiscal year 1999, up from $4.5 billion just two years before, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

The drugs also can be difficult to take. They must be taken on a strict schedule, and patients must remain on them for life. "Although some follow drug regimens nearly perfectly, perfect adherence is difficult," says Murray. "However, patients need to know that poor adherence to drugs may set them up for resistance."

Other pills prescribed to combat the side effects of anti-HIV drugs complicate the regimen. Eppich's day, for example, typically begins around 6:30 a.m. with a trip to the refrigerator, where one of his medications is kept. He then mixes the drug with a liquid and injects it into his side. Then he starts taking the first round of the 60-plus pills he takes every day. It's an hour and a half before he can start his day.

While the drugs keep the virus at bay, they often can make him feel less than healthy. He's nauseated sometimes and tired. Then there's another problem that he jokes about, but finds troublesome nonetheless. "I call it the eternal diarrhea," he says. "It's a part of life."

As more people have taken the drugs, more has become known about this side effect and others. Particularly troubling side effects include liver toxicity, nerve damage, diabetes, high cholesterol levels and unusual accumulations of fat in the neck and abdomen.

Physicians such as the University of Minnesota's Henry have monitored these effects and have listened to their patients. As a result, medical wisdom has changed. In February 2001, federal treatment guidelines changed significantly. Instead of recommending aggressively treating new AIDS patients with drugs, the guidelines now call for waiting until the immune system weakens significantly or until HIV in the blood reaches certain levels.

The reason for this, says Henry, who was an international advocate for this change in philosophy, is that toxicities linked with the use of AIDS drugs appear to outweigh the benefits of early treatment with the drugs.

False Complacency

As the specter of AIDS receded, physicians, researchers and AIDS advocates began to notice that the effectiveness of the prevention message--the call for safe sex and drug practices made so stridently by AIDS advocates--also seemed to ebb.

The incidence of HIV infections began to climb in the late 1990s. So did the incidence of some sexually transmitted diseases--such as gonorrhea--that are closely linked with the type of behavior associated with HIV transmission and are believed by some researchers to even play a role in HIV transmission.

Physicians and AIDS advocates believe these events may be linked to the development of the AIDS drugs. A new generation of people in AIDS risk groups, experts say, now appears to believe that the drugs will protect or cure them of the virus and that an AIDS diagnosis today isn't serious.

"I hear about this all the time from patients," said Schacker, who sees patients at a Minneapolis clinic. "There is this belief that the drugs are so powerful that they can abandon safe sex practices. I am very concerned about it, and it's safe to say that [other researchers] are, too."

So are AIDS advocates such as Project Inform's Delaney. He says some of the problems are caused by unrealistic expectations created by pharmaceutical companies.

"There were some overly cheery drug ads," Delaney says. "The message was, `Don't worry about AIDS. It makes you prettier, it makes you sexier, it makes you stronger.'"

Researchers, physicians and advocates are beginning to target the issue and debate solutions. One researcher, Simon Rosser, Ph.D., M.P.H., of the University of Minnesota's Program in Human Sexuality, believes that an old tool, safe sex public health campaigns, needs to be dusted off and--more significantly--updated.

Rosser, who studies transmission of sexually transmitted diseases and the psychology involved, notes that dramatic advances have been made in treating AIDS. Yet little has been done, he says, to tailor public health messages and find ways to make them more effective.

"Essentially, we are using the same techniques that were used in the 1980s," Rosser says.

Delaney echoes Rosser's concerns, but says that researchers also need to make sure they remain vigilant in their fight against the disease. In his opinion, some of the urgency to find new treatments for AIDS may have been lost.

"The urgency of the old days is past, so the research is drifting in the doldrums of the past," Delaney says. "We're not going to let that happen."

What's Ahead?

As the third decade of AIDS begins, physicians, patients and advocates find themselves looking ahead while still dealing with issues like prevention that have been contended with since the historic CDC report in 1981. A cure, once thought to be imminent, is still years away.

Despite this, those within the AIDS community of researchers, patients and advocates believe that progress has been made against the disease. Researchers know more than ever about the virus, experts say. That there are debates about treatment guidelines also is an advance, since once there were no treatments. The highly visible role in public debate played by AIDS patients and advocates has also helped to lift the stigma once associated with the disease, as well as helped ensure public funding for research and prevention.

The challenge now, experts say, is to bring the tools that have made progress against AIDS in the United States to other countries. High on the list are Africa and Asia, where lack of education and medicine have allowed the virus to spread and kill nearly unchecked.

Project Inform, for example, plans to help find cheaper tools for the diagnosis of HIV and effective ways to lobby the government for increased funding of the international AIDS effort. It may not seem like much, says Delaney and other experts, but perhaps the main lesson from the struggle against AIDS is that the fight will be a long one and that small advances add up.

"We haven't lost hope," says Murray.

Ann Christiansen Bullers is a free-lance writer in Prairie Village, Kan.

COPYRIGHT 2001 U.S. Government Printing Office

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group