Abstract

This survey found that less than 15% of Canadian sleep centres have developed programs for the psychological treatment of insomnia. One in five Canadians suffer from insomnia: the most common sleep complaint confronting health care practitioners. With increasing evidence of the importance of quality sleep for optimal daytime functioning, it is timely to advocate for the development of psychologically-based insomnia programs within Canadian sleep centres. Closer collaboration between clinical psychologists and family physicians in managing insomnia is also required. This paper highlights issues (related to the identification and treatment of sleep disorders) for clinical training of psychologists in Canadian Ph.D. programmes and internship sites.

Insomnia is a complaint based on the patient's perception of insufficient nocturnal sleep and adverse daytime functioning (tiredness, irritability, impairments in memory and concentration, etc.), which can give rise to emotional distress and lost productivity. Studies of the prevalence of insomnia in the general population indicate a median rate for all types of insomnia (mild to severe) of about 35%; 10-15% have moderate to severe symptoms (Ohayon, Caulet, & Guilleminault, 1997; Sateia, Doghramji, Hauri, & Morin, 2000). Epidemiological surveys consistently report that the elderly (Bixler, Kales, Soldatos, Dales, & Healey, 1979; Mellinger, Baiter, & Uhlenhuth, 1985), those with a chronic medical illness (Mellinger et al., 1985; Sutton, Moldofsky, & Badley, 2001), and those with a psychiatric disorder (Ford & Kamerow, 1989; Morin & Ware, 1996) have a higher incidence of difficulty with sleep. In a review of insomnia prevalence studies, Walsh arid Ustun (1999) also found evidence that problematic sleep is more common in women and in lower socioeconomic classes.

Sleep disturbances, including insomnia, may be associated with psychiatric conditions. Patients with a psychiatric disorder often complain of disturbed sleep - a finding that has been supported by objective measurement in the sleep laboratory (Benca, Obermeyer, Thisted, & Gillin, 1992). Those with the complaint of chronic insomnia may be either diagnosable with or are at risk for developing a psychiatric condition. Data from two longitudinal epidemiological studies of adults demonstrate a connection between sleep disturbance and depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders (Ford & Kamerow, 1989; Mellinger et al., 1985). Ford and Kamerow found that individuals with unresolved insomnia had significantly higher rates of subsequent episodes of both depression and anxiety disorders at a one-year follow-up compared with those whose insomnia was resolved. Thus, there is a greater risk for recurrence of depressive episodes in patients with a history of insomnia (Breslau, Roth, Rosenthal, & Andreski, 1996; Ford & Kamerow, 1989). Ford and Kamerow's study also implicated the complaint of insomnia as an early indication of a prodromal psychiatric disorder. They suggested that treatment of the insomnia may be a preventative measure. The finding that residual insomnia after the initial treatment of depression in elderly patients predicted relapse (Reynolds et al., 1997) reinforces this idea. Ohayon and Roth (2003) found that in 44% of new cases with an anxiety disorder, the insomnia appeared after the anxiety symptoms, whereas, in 41% of first-episode mood disorder cases and in 56% of recurrent depressive episode cases, insomnia preceded the mood disorder.

Such findings can be understood in terms of the concept of rollback, whereby the process of reintegration recapitulates, in reverse order, the process of decompensation (Detre & Jarecki, 1971). Rollback is individual-specific (Fava & Kellner, 1991), and each individual possesses a unique amalgam of cascading elements, such as insomnia (Bilsbury & Richman, 2002), with residual symptoms as powerful predictors of relapse (Fava, Fabbri, & Sonino, 2002).

In addition to possible contribution of insomnia in the genesis of depression, depression may conversely lead to insomnia through cither perpetuating factors such as learned behaviours or pharmacological interventions for depression. Certain antidepressants improve sleep in depressed patients, whereas others (e.g., fluoxctinc) can disrupt sleep (Brunello et al., 2000; Rush et al., 1998). When monitoring patients' progress in the treatment of depression, whether non-pharmacological or pharmacological, the health care provider should inquire about any residual insomnia that might need attention.

Poor quality of sleep not only affects the individual patient, but society as well, in the form of lost productivity, increased health care consumption, and large-scale accidents. Epidemiological and longitudinal studies indicate that people with chronic insomnia have memory complaints, poorer work performance, more work-related accidents, increased absenteeism, and receive fewer promotions than those without a sleep problem (Kalter & Uhlenhuth, 1992; Johnson, & Spinweber, 1983; Leger, Cuilleminault, Bader, Levy, & Paillard, 2002). As the most common patient sleep complaint confronting health care practitioners today, chronic insomnia affects 20% of Canadians (Ohayon et al., 1997; Sutton et al., 2001) and is a significant contributor to health care utilization (Hatoum, Kong, Kania, Wong, & Mendelson, 1998; Simon & VonKorff, 1997), possibly by impairing the immune system (Benca & Quintans, 1997; Irwin, 2002; Savard, Laroche, Simard, Ivers, & Morin, 2003). Several high-profile sleep-related accidents such as the space shuttle Challenger explosion, the Exxon Valdez oil spill, and the Chernobyl and Three Mile Island nuclear accidents (Mitler et al., 1988) illustrate the catastrophic effect that sleep loss may have on a person and on society.

Costs directly related to insomnia in 1991 in the United States were estimated to be in the region of $11 billion. Indirect costs such as reduced productivity at work were estimated to be $30-$35 billion (Chilcott & Shapiro, 1996; Roth, 1996). In a more recent review, Walsh and Ustun (1999) estimated the direct cost of insomnia to the United States in 1995 at almost $14 billion. Included in their estimate were the costs for medications (both nonprescription and prescription) and alcohol; outpatient visits to physicians, psychologists, and social workers; evaluation and treatment by sleep specialists; mental health services specifically for insomnia; inpatient care for insomnia; and nursing home care of the elderly with insomnia. Indirect costs related to insomnia were those resulting from reduced work productivity, increased motor vehicle accidents, and secondary medical expenses not directly related to insomnia. Walsh and Ustun did not calculate indirect costs owing to the lack of sufficient data, but they did suggest that the estimated amount would be more than $14 billion. The successful diagnosis and treatment of insomnia should reduce both the direct and indirect cost of poor sleep on the individual and society.

Despite the impairment in functioning, a high prevalence rate, and the cost to the individual and society, insomnia remains underdiagnosed and under-treated. Though many of the complaints of insomnia can be related to another primary condition (e.g., medical, psychiatric, or another sleep disorder) a majority of insomnia patients present with persistent primary insomnia (Buysse et al., 1994; Coleman et al., 1982). Primary insomnia is the subjective difficulty (lasting for at least one month) of initiating or maintaining sleep, or of nonrestorative sleep, which causes significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning, and is not associated with another sleep, medical, or mental disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 1994).

As with any disorder, appropriate diagnosis and optimal treatment are required to manage the complaint of insomnia. For those persons whose insomnia is secondary to a medical, psychiatric, or other sleep disorder, the primary condition ought to be treated first. Even when this treatment is successful, it should not be assumed that the insomnia has necessarily remitted. The focal treatment of insomnia may be required after the primary condition has resolved.

Heart and lung diseases, neurological degenerative disorders, and pain are common medical conditions that negatively affect sleep (Katz & McHorney, 1998). Depression and anxiety are the two most frequent psychiatric causes of insomnia (Breslau et al., 1996; Buysse et al., 1994; Ford & Kamerow, 1989; Ohayon et al., 1997; Ohayon & Roth, 2003). Stress has also been associated with insomnia (Hall et al., 2000; Healy et al., 1981; Morin, Rodrigue, & Ivers, 2003; Sutton et al., 2001). It would corne as little surprise if future work were to demonstrate that stress ranks as prominently as depression and anxiety in the initiation and maintenance of both acute and chronic insomnia. Sleep disorders that may result in a complaint of insomnia include sleep apnea, periodic limb movement disorder, restless legs syndrome, narcolepsy, and circadian rhythm disorders. In most cases, a referral to a sleep disorders centre is necessary.

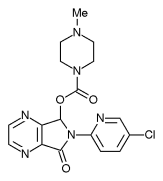

Pharmacological interventions are the most commonly used treatment for insomnia. Not surprisingly, primary care physicians initiate 80% of hypnotic drug prescriptions (Ohayon & Caulet, 1995). Hypnotic medications are advocated as an initial treatment in cases where the insomnia is acute and there is an identifiable precipitating (actor such as grief. Benzodiazepines, some antidepressant medications with sedating properties, and the newer nonbenzodiazepines (e.g., zopiclone, zaleplon) are the three categories of hypnotic medications most commonly used for insomnia (Walsh & Schweitzer, 1999). Studies using placebo-controls have demonstrated the efficacy of hypnotic medication over the short-term (4 weeks) in the management of insomnia (Smith et al., 2002). The long-term efficacy of pharmacological interventions, however, is clouded by concerns about tolerance, daytime sedation, increased risk of falls, and cognitive impairment (Holbrook et al., 2000). There is no systematic data evaluating the long-term use of hypnotics, but the reality is such that many patients remain on this treatment for years (Uhayon & Caulet, 1995).

For chronic insomnia, a sleep disruption lasting longer than six months, nonpharmacological treatments are preferable (Morin, Hauri, et al., 1999). With such chronic cases, the focus of treatment is on the learned behaviours that perpetuate poor sleep, rather than the precipitating factor. The majority (70-80%) of patients with primary insomnia benefit from psychological interventions (Morin, Hauri, ct al., 1999). Mainstream modalities include re-associating temporal and environmental stimuli with falling asleep (stimulus control therapy; Bootzin & Nicassio, 1978), restricting time in bed to improve sleep efficiency (Spielman, Saskin, & Thorpy, 1987), lowering somatic and cognitive arousal (relaxation training), identifying and changing cognitive distortions about sleep (cognitive therapy), and lifestyle alterations (sometimes referred to as "sleep hygiene") to eliminate behaviours that interfere with sleep (Zarcone, 2000; Bilsbury & Valdivia, 2003).

In a meta-analysis, Morin, Culbert, and Schwartz (1994) found that the most effective interventions were stimulus control and sleep restriction. Relaxation therapy can be quite useful for treating the night time complaints related to insomnia but limited in improving daytime functioning (Means, Lichstein, Epperson, & Johnson, 2000). Cognitive therapy as a stand-alone therapy has not been empirically validated. However, cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment of chronic insomnia has demonstrated both short- and long-term benefits (Backhaus, Hohagen, Voderholzer, & Riemann, 2001; Edinger, Wohlgemuth, Radtke, Marsh, & Quillian, 2001) by addressing cognitive and physical hyperarousal, rumination about sleep, and excessive concern regarding sleep loss. Sleep hygiene, though informative to patients, has not been as effective as the other interventions when used as a single treatment (Schoicket, Bertelson, & Lacks, 1988).

In a comparative meta-analysis of pharmacological and behavioural therapy for primary insomnia, both interventions demonstrated similar outcomes in the short-term (Smith et al., 2002). The efficacy of long-term hypnotic use remains questionable since there is an absence of data indicating that gains made initially with pharmacological interventions are maintained upon withdrawal of the medication. However, the long-term benefits of the nonpharmacological interventions, primarily cognitive behavioural therapy, have been demonstrated in those over the age 55 (Morin, Colecchi, Stone, Sood, & Brink, 1999). There is also evidence that brief psychological treatment (8-12 sessions) is more cost-effective than pharmacological interventions for the treatment of chronic insomnia (Morin, Culbert, & Schwartz, 1994; Pcrlis, Smith, Cacialli, Nowakowski, & Orff, 2003). Perlis et al. (2003) and Smith et al. (2002) discuss cost/benefit considerations of long-term pharmacotherapy (sedative hypnotic maintenance therapy) and behavioural treatment. An additional consideration is that when patients with chronic insomnia were asked about the two types of interventions, the nonpharmacological interventions were rated as more acceptable than the pharmacological treatments (Morin, Gaulicr, Barry, Kowatch, 1992; Vincent & Lionbcrg, 2001). Unfortunately, they are underutilized relative to pharmacological interventions, which remain the usual form of treatment for a person with acute and chronic insomnia.

Family physicians arc the primary health care providers treating insomnia (Ohayon & Caulet, 1995). However, a subsection of those patients with unremitting insomnia will be referred for specialized assessment at a sleep centre to establish a differential diagnosis. Since sleep clinics are an identifiable resource for information and treatment for those with a sleep disturbance, it is of interest and importance to know how Canadian sleep centres treat people with symptoms of insomnia. Therefore, we surveyed 83 Canadian sleep centres as to the services and professional resources available for patients with complaints of insomnia.

Method

All 83 sleep centres listed on the Canadian Sleep Society website (www.css.to/sleep/centers.htm) were contacted by telephone from October 2000 to May 2001. These included facilities that were privately and/or provincially funded, and were clinically and/or research oriented. Their locations are shown in Table 1.

Using a 10-item questionnaire (see Appendix), a representative from each centre was asked about the type of services provided to patients complaining of insomnia. If a site indicated that they indeed provided services to patients with insomnia, more detailed inquires were made into the types of referral sources, the assessment procedures (interview or sleep study), the use of questionnaires and sleep logs, and the kinds of treatment modalities offered. By "interview," we mean a detailed review of the patient's sleep history, environmental factors, medication use, psychiatric and medical history, and family history. By "sleep study," we refer to overnight polysomnography, which records several physiological parameters (electrical activity of the brain, eyes, muscles, heart, oxygen saturation, and respiration). The sleep study is considered the "gold standard" for objectively measuring sleep.

The response rate to the survey was 84%, with 70 out of the 83 centres agreeing to participate.

Results

The survey addressed both the assessment and the treatment of complaints of insomnia at Canadian sleep centres. A flow chart of responses is shown in Figure 1. We were unable to collect data from 13 (13/83, 16%) sleep centres for a variety of reasons: disconnected telephone, no response to our calls or messages, or they were not available until after the date set for ending the survey. The following results are based on the 70 sleep centres that completed our survey.

Most (84%, 59/70) of the clinics were willing to provide an assessment to a patient with a complaint of insomnia (i.e., interview, sleep study or both) to determine if another sleep disorder (e.g., respiratory disorders, movement disorders, or narcolepsy) was present. The 11 (11/70, 16%) remaining sleep centres refused referrals for insomnia.

Just 9 of the 70 sleep centres (13%) had psychological treatment services for insomnia as part of their program. These sleep clinics either provided treatment within their clinic, or they had an established treatment provider (psychologist) to whom patients could be referred. Most centres, 87% (61 of the 70), indicated that they do not provide psychological treatment to patients complaining of insomnia owing to the specialized orientation of the facility (e.g., pure research or respiratory disorders).

Although not directly involved in the treatment of insomnia, 16 sleep centres (23%, 16/70), would refer appropriate patients to one of the nine centres (previously mentioned) that incorporate psychological treatment of insomnia into their programme mandate.

Twenty-two sleep centres (22/70, 31%) that either did not have access to, or were unaware of, psychological services for insomnia treatment, were able to provide the patient with a brief review of sleep hygiene (e.g., limit caffeine intake) or/and the attending physician would prescribe a hypnotic medication. The remaining 12 sleep centres, after completing the assessment, referred the patients back to the family physician for the pharmacological management of insomnia.

Discussion

This survey showed that only nine Canadian sleep clinics are equipped to provide psychological treatment to patients with insomnia in a programmatic fashion. There are two main reasons as to why few of the sleep centres provide comprehensive services: the first relates to the mission of many modern sleep centers, and the second concerns supply/demand economics in service provision, which relates in turn to training issues.

With respect to the development of sleep centres, there has been an increasing recognition in the medical profession of the serious health consequences of sleep-disordered breathing. Although population-based studies indicate that only 2% of women and 4% of men may have obstructive sleep apnea (Young et al., 1993), diagnostically, this problem accounts for 68% of referrals to sleep centres (Punjabi, Welch, & Strohl, 2000) compared to 24% two decades ago (Coleman et al., 1982). Insomnia, which affects 20% of the Canadian population, does not necessitate a referral to a sleep centre for an overnight diagnostic study unless the complaint of insomnia is secondary to a suspected sleep-related breathing or movement disorder (Standards of Practice Committee of the American Sleep Disorders Association, 1995). Our findings suggest that the interaction between long waiting lists and the limited utility of sleep studies in diagnosing insomnia has influenced sleep centres to triage their patients and utilize resources for only those patients requiring a sleep study to determine diagnosis and treatment. Thus, a majority of the referrals to Canadian sleep centres are for sleep-related breathing or movement disorders, and not for insomnia.

It is noteworthy that the allocation of sleep centres is very unequal across Canada (see Table 1 ) with a disproportionately large number (73%) of sleep centres located in the province of Ontario. One of the unique characteristics of Ontario is represented by the privatcly run centres (typically designed to diagnose and treat sleep-related breathing disorders), which are able to bill for both professional and technical components of conducting sleep studies (see Ministry of Health and Long-term Care of Ontario guidelines for diagnostic and therapeutic procedures; http://www. gov.on.ca/MOH/english/program/ohip/sob/ physserv/physserv_mn.html). Other provinces only reimburse if the sleep centre is affiliated with a hospital. It would seem that the large discrepancy between Ontario and other provinces reflects the disparate methods in the funding available for sleep studies rather than patient demand. The long waiting lists (up to one year) seen in the Atlantic provinces reflect limited resources, whereas the shorter waiting periods of 2-4 weeks in Ontario reflect a better demand/supply equation, at least for sleep-related breathing disorders.

Our finding that just nine sleep centres across Canada have the resources for the psychological treatment for insomnia indicates that there is a tremendous need to develop behavioural sleep medicine (health psychology) training programs incorporating service provision, as well as research and teaching. As an example of the scope of the unmet need in Canada, one sleep clinic from the survey accrued a waiting list (in just one year) of over 100 patients with insomnia complaints. Another sleep centre routinely refers patients with insomnia to a second centre in the area that specializes in research on insomnia. Unfortunately, this second sleep centre does not accept these patient referrals since it conducts only research.

In regard to the supply/demand economics in service provision, Perlis et al. (2003) estimate that in the United States there are only 100-200 trained and experienced behavioural sleep medicine (health psychology) specialists available to treat the 10% of the population (28 million people) with chronic insomnia. Stepanski and Perlis (2000) identified only 21 universities in the United States and Canada that offer formal training in sleep, 11 of which have a sleep rotation within their internship program. This is, in part, because of a lack of psychologists trained in the behavioural sleep medicine component of health psychology. In an article published in this journal in 1997, De Koninck highlighted the impact that sleep has on several aspects of psychological functioning, and indicated that researchers and practitioners in psychology should be more attentive to sleep-related issues when working with clients or research participants. De Koninck also encouraged the integration of the topic of sleep into clinical psychology curricula. Training programs typically teach clinical psychologists to be aware of sleep problems as a clinical feature of depression and certain other psychiatric disorders, but they often neglect topics such as sleep apnea, narcolepsy, and restless legs. Such conditions can disturb sleep, reduce daytime performance, negatively affect mood and, in essence, mimic a mood disorder.

Advocacy is required to re-incorporate insomnia treatment into the mandate of sleep clinics. A second avenue for psychologists with expertise in treating insomnia is the development of a closer collaboration with family physicians. Based on community surveys, most patients complaining of insomnia first come to the attention of their primary care physician (Ohayon & Caulet, 1995), although many of these physicians will not have had the benefit of training in the held of sleep medicine (Chesson et al., 2000; Molinc & Zendell, 199S; Orr, Stahl, Dcnncut, & Reddington, 1980; Rosen, Rosekind, Rosevear, Cole, & Dement, 1993). As a result, the type of treatment received will depend on the physician's awareness of treatment options and the availability of specialized services. According to one report, evaluating physician responses to a hypothetical insomnia case, only half of the primary care physicians included questions about sleep in their history taking (Rveritt, Avom, & Baker, 1990). Compounding the problem, another survey showed that 70% of patients with chronic insomnia do not bring up their sleep problem with the physician (Gallup Organization, 1995) for a variety of reasons, including the belief that their insomnia is untreatable. Twenty-six percent of patients with insomnia mention their sleep problem only when visiting their physician for a medical or psychiatric disorder, which may explain the high association between secondary insomnia and medical/psychiatric disorders in primary care patients. Only 5% of patients with chronic insomnia visit a physician specifically to discuss it. Thus, the accurate assessment of sleep is negatively affected by a system where the patient does not offer the necessary information, and the physician often fails to ask routine questions about sleep. Leaving a large portion of these patients untreated has the potential to result in excessive patient morbidity, health care costs, and lost productivity. The heterogeneity of causes and treatments, and the level of chronicity makes insomnia a challenging therapeutic task for the family physician alone (Hajak, 2000), and apt psychological help would be welcomed.

Psychologists, with their sapiential authority in empirically validated treatments and quantitative single case methods, are ideally poised to treat insomnia and insomnia sensitivity (the state where nighttime preoccupation and an inflated perception of next-day consequences causes impairment beyond that of the actual number of hours of sleeplessness - Bilsbury & Ruyak, 2001).

Finally, a word about training. The field of sleep medicine has grown rapidly in the last two decades and the demand for psychologists trained in this area far exceeds the current Canadian supply. There is a need for specialized training in sleep disorders in our clinical programmes and internship settings to meet the needs of the 20% of Canadians with sleep difficulties, particularly those with insomnia, where psychologists have such a central role to play.

We conclude with the words of a pioneer sleep researcher and clinician, W. C. Dement:

We may expect that doctors and other health professionals will begin to feel good about managing insomnia, and confident that they can be successful. We may further hope that word will spread and that people with insomnia will at last get the treatment they deserve. (Foreword to Morin, 1993, p. xii)

A portion of this work was presented at the (irst Canadian Sleep Society meeting held in May 2001.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Dr. M. Kryger for his input on the discrepancy in number of sleep centres between the provinces.

Peggy Ruyak would like to acknowledge the financial support of the Killam Society.

Resume

Cette enquete demontre que moins de 15 % des centres du sommeil canadiens ont mis sur pied des programmes visant le traitement psychologique de l'insomnie. Un Canadien sur cinq souffre d'insomnie, la plainte relative au sommeil la plus commune que doivent soigner les praticiens des soins de la sante. Compte tenu des evidences croissantes de l'importance de la qualite du sommeil pour un fonctionnement journalier optimal, il vient a propos de preconiser la mise sur pied de programmes de lutte contre l'insomnie bases sur 1% psychologie au sein des centres du sommeil canadiens. Une collaboration plus etroite entre les psychologues cliniques et les medecins de famille dans la gestion de l'insomnie est egalement requise. Cet article met en evidence les questions entourant la formation clinique des psychologues dans les etablissements canadiens dans l'identification et le traitement des troubles du sommeil.

* This paper was accepted by the previous editor, Dr. Vic Catano/Cet article a ete accepte par le Redacteur en chef precedent, Vic Catano

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Backhaus, J., Hohagen, F., Voderholzcr, U., & Ricmann, D. (2001). Long-term effectiveness of a short-term cognitive-behavioral group treatment for primary insomnia. Eurpean Arvhives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 2JA 35-41.

Baiter, M. B., & Uhlcnhuth, E. H. (1992). New cpidcmiologic findings about insomnia and its treatment, Journal of XlinicA pSYCHI8ATRY,, 34-39.

Benca, R. M., Obcrmcycr, W. H., Thistcd, R. A., & Gillin, C. (1992). Sleep and psychiatric disorders: A metaanalysis. ArcAive; Archives of General Psychiatry, 49, 651-668.

Benca, R. M., & Quintans, J. (1997). Sleep and host defenses: A review. Sleep 2, 1027-1037.

Bilsbury, U. D., & Richman, A. (2002). A staging approach to measuring patient-centred subjective outcomes. Acia Psuciatriac Scandinacic i06(Suppl. 414), 5-40.

Bilsbury, C. D., & Ruyak, P. S. (2001). Insomnia sensitivity. Sleep Mancm, 2, 569.

Bilsbury, C. D., & Valdivia, 1. (2008). Flow into sleep. & Mf 4, 253.

Bixler, E. O., Kales, A., Soldatos, C. R., Kales, J. D., & Healey, S. (1979). Prevalence of sleep disorders in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. American Journal of Psychiatry , 1257-1262.

Bootzin, R. R., & Nicassio, P. M. (1978). Behavioral treatments for insomnia. In M. Hersen, R. Eissler, & P. Miller (Eds.), Progress in behaciour modification (pp. 1-45). New \brk: Academic Press.

Breslau, N., Roth, T., Rosenthal, L., & Andreski, P. (1996). Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: A longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Son'giy Biological Psyuchi8tary .39, 411-418.

Brunello, N., Armitage, R., Feinberg, I., HolsboerTrachsler, E., Leger, D., Linkowski, et al. (2002). Depression and sleep disorders: Clinical relevance, economic burden and pharmacological treatment. Neuropsychobiolgy,, 42, 107-119.

Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Kupfer, D. J., Thorpy, M. J., Bixler, E., Manfredi, R., et al. (1994). Clinical diagnoses in 216 insomnia patients using the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD), DSM-IV and ICD-IO categories: A report from the APA/NIMH DSMIV field trial. SkqD, J 7, 630-637.

Ghesson, A., Jr., Hartse, K., Anderson, W. M., Davila, D., Johnson, S., Littner, M., et al. (2000). Practice parameters for the evaluation of chronic insomnia. Sleep, 2.3, 237-241.

Chilcott, L. A., & Shapiro, C. M. (1996). The socioeconomic impact of insomnia: An overview. PAarMacoKcoMomi, 70, 1-14.

Coleman, R. M., Roffwarg, H. P., Kennedy, S. J., Guillerninault, C., Cinque, J., Cohn, M. A., et al. (1982). Sleep-wake disorders based on a polysomnographic diagnosis: A national cooperative study. Journal of the American Medical Association, 247, 997-1003.

De Koninck,J. (1997). Sleep, the common denominator for psychological adaptation. Canadian Psychology, 38, 191-195.

Dctrc, T. P., &Jarccki, II. G. (1071). Modern psychiatric treatment. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Company.

Edinger, J. D., Wohlgemuih, W. K., Radtke, R. A., Marsh, G. R., & Quillian, R. E. (2001). Cognitive behavioral therapy for treatment of chronic primary insomnia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of l.he American Medical Association, 265, 1856-1864.

Everitt, D. E., Avom.J., & Baker, M. W. (1990). Clinical decision making in the evaluation and treatment of insomnia. American Journal of Medicine, 69, 357-362.

Fava, G. A., Fabbri, S., & Sonino, N. (2002). Residual symptoms in depression: An emerging therapeutic target. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacolgy & Biological Psychiatry, 26, 1019-1027.

Fava, G. A., & Kellner, R. (1991). Prodromal symptoms in affective disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 828-830.

Ford, D. K., & Kamerow, D. B. (1989). Epidemiologie study of disturbances and psychiatric disorders: An opportunity for prevention. Journal of the American Medical Association, 262, 1479-1484.

Gallup Organization. (1995). Sleep in America. Princeton, NJ: Gallup Organization.

Hajak, G. (2000). Insomnia in primary care. Sleep, 23, S54-S63.

Hall, M., Buyssc, D. J., Nowcll, P. D., Nofzingcr, E. A., Houck, P., Reynolds, C. F., et al. (2000). Symptoms of stress and depression as correlates of sleep in primary insomnia. Psychosomatic Medicine, 62, 227-230.

Hatoum, H. T., Kong, S. X., Kania, C. M., Wong, J. M., & Mendelson, W. B. (1998). Insomnia, health-related quality of life and healthcare resource consumption: A study of managed-care organization enrollees. Pharmacoeconomics, J4, 629-637.

Healy, E. S., Kales, A., Monroe, L.J., Bixlcr, E. ()., Chamberlin, K., & Soldates, C. R. (1981). Onset of insomnia: Role of life-stress events. Psychosomatic Medicine, JJ, 439-451.

Holbrook, A. M., Crowther, R., Loiter, A., Cheiig, C., & King, D. (2000). Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in the treatment of insomnia. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 762, 225-233.

Irwin, M. (2002). Effects of sleep and sleep loss on immunity and cytokines. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 16, 503-512.

Johnson, L., & Spinweber, C. (1983). Quality of sleep and performance in the Navy: A longitudinal study of good and poor sleepers. In C. Guilleminault & E. Lugaresi (Eds.), Sleep/wake disorders: Natural history, epidemiology, and long-term evaluation (pp. 13-28). New York: Raven Press.

Katz, D. A., & McHorney, C. A. (1998). Clinical correlates of insomnia in patients with chronic illness. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158, 1099-1107.

Leger, D., Guilleminault, C., Bader, G., Levy, E., & Paillard, M. (2002). Medical and socio-professional impact of insomnia. Sleep, 25, 621-625.

Means, M. K., Lichstein, K. L., Epperson, M. T., & Johnson, C. T. (2000). Relaxation therapy for insomnia: Nighttime and day time effects. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38, 665-678.

Mellinger, G. D., Baiter, M. B., & Uhlenhuth, E. H. (1985). Insomnia and its treatment: Prevalence and correlates. Archives of Generai Psychiatry, 42, 225-232.

Mitler, M. M., Carskadon, M. A., Czeisler, C. A., Dement, W. C., Dinges, D. F., & Graeber, R. C. (1988). Catastrophes, sleep and public policy: Consensus report. Sleep, 11, 100-109.

Moline, M., & Zendell, S. (1993). Sleep education in professional training programs. Sleep !Research, 22, 1.

Morin, C. M. (1993). Insomnia: Psychological assessment and management. New York: Guilford.

Morin, C. M., Colecchi, C., Stone, J., Sood, R., & Brink, D. (1999). Behavioral and pharmacological therapies for late-life insomnia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of'the American Medical Association, 281, 991-999.

Morin, C. M., Culbert, J. P., & Schwartz, S. M. (1994). Nonpharmacological interventions for insomnia: A meta-analysis of treatment efficacy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 151, 1172-1180.

Morin, C. M., Gaulier, B., Barry, T., & Kowatch, R. A. (1992). Patients' acceptance of psychological and pharmacological therapies for insomnia. Sleep, 15, 302-305.

Morin, C. M., Hauri, P. [., Espie, C. A., Spielman, A. J., Buysse, D. J., & Bootzin, R. R. (1999). Nonpharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine review. Sleep, 22, 1134-1156.

Morin, C. M., Rodrigue, S., & !vers, H. (2003). Role of stress, arousal, and coping skills in primary insomnia. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 259-267.

Morin, C. M., & Ware,J. C. (1996). Sleep and psy-chopathology. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 5, 211-224.

Ohayon, M. M., & Caulet, M. (1995). Insomnia and psychotropic drug consumption. Progress NeuroPsychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 19, 421-431.

Ohayon, M. M., Caulet, M., & Guilleminault C. (1997). How a general population perceives its sleep and how this relates to the complaints of insomnia. Sleep, 20, 715-723.

Ohayon, M. M., & Roth, T. (2003). Place of chronic insomnia in the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 37, 9-15.

Orr W., Stahl, M., Denneut, W., & Reddington, D. (1980). Physician education in sleep disorders. Journal of Medical Education, 55, 367-369.

Perils, M. L., Smith, M. T., Cacialli, D. O., Nowakowski, S., & Orff, H. (2003). On the comparability of pharmacotherapy and behavior therapy for chronic insomnia: Commentary and implications. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 54, 51-59.

Punjabi, N. M., Welch, D., & Strohl, K. (2000). Sleep disorders in regional sleep centers: A national cooperative study. Sleep, 23, 471-480.

Reynolds, C. F. Ill, Frank, E., Iiouck, P. R., Mazumdar, S., Dew, D. A., Cornes, C., et al (1997). Which elderly patients with remitted depression remain well with continued interpersonal psychotherapy after discontinuation of antidepressant medication? American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 958-962.

Rosen, R., Rosekind, M., Rosevear, C., Cole, W., & Dement, W. (1993). Physicians' education in sleep and sleep disorders: A national survey of US medical schools. Sleep, 16, 249-254.

Roth, T. (1996). Social and economic consequences of sleep disorders. Sleep, 19, S46-S47.

Rush, A. J., Armitage, R., Gillin, J. C., Yonker, K. A., Winokur, A., Moldofsky, H., et al. (1998). Comparative effects of nefazodone and fluoxetine on sleep in outpatients with major depressive disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 44, 3-14.

Sateia, M. J., Doghramji, K., Hauri, P., & Morin, O. M. (2000). Evaluation of chronic insomnia. Sleep, 23, 243-263.

Savard, f., Laroche, L., Simard, S., !vers, H., & Morin, C. M. (2003). Chronic insomnia and immune functioning. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65, 211-221.

Schoicket, S. L., Bertelson, A. D., & Lacks, P. (1988). Is sleep hygiene a sufficient treatment for sleep maintenance insomnia? Behavioral Therapy, 19, 183-190.

Simon, G. E., & VonKorff, M. (1997). Prevalence, burden, and treatment of insomnia in primary care. American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 1417-1423.

Smith, M. T., Perlis, M. L., Park, A., Smith, M. S., Pennington, J., Giles, D. E., et al. (2002). Comparative meta-analysis of pharmacotherapy and behavior therapy for persistent insomnia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159, 5-11.

Spielman, A.J., Saskin, P., & Thorpy, M. J. (1987). Treatment of chronic insomnia by restriction of time in bed. Sleep, 10, 45-56.

Standards of Practice Committee of the American Sleep Disorders Association. (1995). An American Sleep Disorders Association report: Practice parameters for the use of polysomnography in the evaluation of insomnia. Sleep, 18, 55-57.

Stepanski, E. J., & Perlis, M. L. (2000). Behavioral sleep medicine: An emerging subspecialty in health psychology and sleep medicine. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 49, 343-347.

Sutton, D. A., Moldofsky, H., & Badley, E. M. (2001). Insomnia and health problems in Canadians. Sleep, 24, 665-670.

Vincent, N., & Lionberg, C. (2001). Treatment preference and patient satisfaction in chronic insomnia. Sleep, 24, 411-417.

Walsh.J., & Ustun, T. B. (1999). Prevalence and health consequences of insomnia. Sleep, 22, S427-S436.

Walsh.J. K., & Schweitzer, P. K. (1999). Ten-year trends in the pharmacological treatment of insomnia. Sleep, 22, 371-375.

Young, T., Palta, M., Dempsey, J., Skatrud, J., Weber, S., & Badr, S. (1993). The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. Netu England Journal of Medicine, 328, 1230-1235.

Zarcone, V. P. (2000). Sleep hygiene. In M. H. Kryger, T. Roth, & W. C. Dement (Eds.), Principles and practices of sleep medicine (4th ed., pp. 657-661). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders.

PEGGY S. RUYAK

CHRISTOPHER D. BILSBURY

MALGORZATA RAJDA

Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre and Dalhousie University

Address correspondence to Peggy S. Ruyak, Sleep Disorders Clinic, Abbie J. Lane Memorial Building, Queen Eli/abelh II Health Sciences Centre, 5909 Veterans' Memorial Lane, Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 2K2.

Copyright Canadian Psychological Association May 2004

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved