A 25-year-old man presented with aching, swollen, scarlet lesions on the tips of all 10 fingers (Figure 1) following a three-day prodrome of worsening sharp pain in his thumbs, little fingers, and lips. His temperature was 38.2[degrees]C (100.8[degrees]F), and he was unable to fully extend his fingers because of throbbing pain. Small, round, crusted lesions resembling recently ruptured blisters lined his lips. Tense, pustular lesions surrounded by a bright border of erythema and some superficial desquamation encircled the fingertips (Figure 2). The patient denied any recent trauma or other lesions. No adenopathy was appreciated. His white blood cell count, blood chemistries, and transaminase levels were within normal limits.

[FIGURES 1-2 OMITTED]

Question

Based on the patient's history, physical examination, and laboratory tests, which one of the following is the correct diagnosis?

[] A. Pompholyx.

[] B. Herpes zoster.

[] C. Herpetic whitlow.

[] D. Endocarditis with Osler's nodes.

[] E. Paronychia.

Discussion

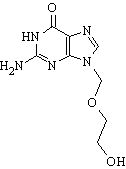

The answer is C: herpetic whitlow. Herpetic whitlow is in the differential diagnosis of any patient with a fingertip infection. Positive results from direct fluorescent antibody tests and viral cultures from the patient's oral and digital lesions confirmed type 1 herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection. Further history revealed that the patient regularly bit his nails.

Herpetic whitlow is an HSV infection of the fingers and toes and may represent a primary infection or a secondary recurrence of type 1 or 2 HSV infection. It occurs primarily in medical personnel and in patients with herpetic stomatitis. Before the advent of universal precautions, herpetic whitlow occurred predominantly in health care professionals inoculated by infected patients. (1) The virus is transmitted via saliva, semen, cervical fluid, and active lesions, and often is introduced through direct contact. (2) Following a short incubation period, painful, coalescing vesicles with surrounding erythema develop. The vesicle fluid usually is serous but may appear purulent in patients with secondary infection. Low-grade fever, malaise, and regional lymphadenopathy also may occur. (3) Treatment involves inhibition of viral replication with acyclovir (Zovirax), valacyclovir (Valtrex), or famciclovir (Famvir); symptomatic pain relief; and treatment of bacterial superinfection. The course typically lasts a few weeks, and healing usually is complete.

Pompholyx, or dyshidrotic eczema, is a nonspecific reaction pattern of unknown etiology that preferentially affects the palms and sides of the fingers. (4) Painful pruritus precedes the appearance of bilateral, symmetrical, clear vesicles that progress to bullae. Desquamation, inflammation, and secondary infection often follow. Attacks normally subside spontaneously within two to three weeks.

Herpes zoster infection results from reactivation of the varicella zoster virus, which lies dormant in the sensory ganglia after primary infection. While its vesicular lesions resemble those of HSV infections, their key distinguishing feature is their distribution. (5) Herpes zoster vesicles typically form a dermatomal distribution throughout the affected nerve, while HSV vesicles form at the distal ends of affected nerves.

Osler's nodes are painful, swollen, violaceous subcutaneous nodules occurring mainly in the pulp of the fingers and toes. They are one of several cutaneous manifestations of bacterial endocarditis, and are caused by septic emboli from acute bacterial endocarditis or small-vessel perivasculitis in subacute bacterial endocarditis. (6)

Paronychia, a localized infection of the perionychium, may be acute or chronic and is characterized by pain, erythema, and swelling of the posterior or lateral nail folds, and subsequent superficial abscess. Acute paronychia commonly results from nail biting or trauma and is typically a mixed infection, with Staphylococcus aureus predominating, whereas chronic paronychia likely represents a multifactorial eczematous condition or fungal infection. (7)

REFERENCES

(1.) Jones JG. Herpetic whitlow: an infectious occupational hazard. J Occup Med 1985;27:725-8.

(2.) Yeung-Yue KA, Brentjens MH, Lee PC, Tyring SK. Herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2. Dermatol Clin 2002;20:249-66.

(3.) Spruance SL, Overall JC Jr, Kern ER, Krueger GG, Pliam V, Miller W. The natural history of recurrent herpes simplex labialis: implications for antiviral therapy. N Engl J Med 1977;297:69-75.

(4.) Crosti C, Lodi A. Pompholyx: a still unresolved kind of eczema. Dermatology 1993;186:241-2.

(5.) Chen TM, George S, Woodruff CA, Hsu S. Clinical manifestations of varicella-zoster virus infection. Dermatol Clin 2002;20:267-82.

(6.) Fitzpatrick TB, Johnson RA, Wolff K, Polano MK, Suurmond D, eds. Color atlas and synopsis of clinical dermatology: common and serious diseases. 3d ed. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1997:623.

(7.) Rockwell PG. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician 2001;63:1113-6.

RAMEY WILSON, M.D.

ALEX G. TRUESDELL, M.D.

TODD C. VILLINES, M.D.

Walter Reed Army Medical Center

Washington, D.C.

COPYRIGHT 2005 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group