UNTIL TWO YEARS AGO, TOM LOWE'S job was about as easy and worry-free as an undercover cop's can get. Lowe, the lead Ecstasy investigator for the Pennsylvania attorney general, spent most of his professional time going to raves--vast dance parties held in abandoned warehouses or clubs and fueled by Ecstasy and electronic music. The dealers he busted, like the parties' patrons, were mostly peaceable white suburban kids, too trusting and naive to think that a cop could have even found a rave. They sold Ecstasy to him eagerly, and often without suspicion, and then he arrested them. Kids like this, more interested in partying with their friends than vetting buyers, were pretty easy pickings for Lowe, who'd cut his teeth making cocaine buys in Detroit. The hardest part of his job, he told me, had been changing the way he dressed to keep up with the latest raver trends, and making sure he knew enough about current electronic music to pass for an earnest, older raver.

But Lowe's job has gotten harder, and the raver act he'd become so good at doesn't play so well anymore. In recent years, the Ecstasy market has expanded beyond the rave scene, and more sophisticated and dangerous drug organizations have begun to elbow in on what had been mostly a friend-to-friend, white suburban trade. Last year, Lowe put some gun-toting Latin Kings gang members in jail for Ecstasy distribution in York, Pa., after a long and difficult investigation. The drug, for Lowe, has left the trusting insularity of the rave scene and begun to move out onto the streets, where dealers are more violent, more profit-conscious, and far more wary about undercover buyers like Tom Lowe. "It's a whole new ballgame," he says. "It's not just white suburban ravers anymore."

The trends Lowe has seen in warehouses and parking lots around suburban Pennsylvania have begun to emerge nationally. The market for Ecstasy has begun to expand from those ravers into a broader user demographic--one that is both older and younger, more racially diverse, and includes people who do their drugs not at big raves but home alone. No longer a niche drug, Ecstasy has begun to attract organized, professional drug gangs. In some cities, the drug is sold on the street alongside crack and heroin, by dealers who thrive on the repeat business afforded by addicts and junkies; since Ecstasy is not itself physically addictive, they've begun cutting it with drugs that are, like methamphetamines. Ecstasy, in other words, is becoming a street drug. "We're seeing the same things with Ecstasy that we did with cocaine in 1979," says Mark Kleiman, a professor of public policy at UCLA. The user group is expanding, prices are declining, and professional gangs are muscling in. If this new trend continues, Ecstasy may no longer be the largely self-contained, relatively low-risk diversion that it has been, but a potential gateway to addiction and violence for millions of young Americans.

Can this transformation be stopped? Some experts think so, but the solution probably can't be found on either side of the conventional drug-policy debate. The government's current anti-Ecstasy enforcement system, favored by law-and-order elected officials, clearly isn't working: Ecstasy's "streetification" is happening despite a series of tough new laws aimed at cracking down harder on its use. On the other hand, legalizing Ecstasy, as many libertarians would have us do, might eliminate the criminal underworld, but only at the cost of dramatically increasing the number of users, many of them teenagers. And Ecstasy might not be as harmless as its advocates seem to think.

Club Crackers

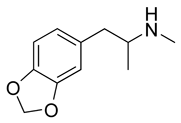

Ecstasy is the most common street name for a synthesized chemical, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA), which was originally patented in 1914 by German chemists working for Merck. Nobody's been able to document what purpose they had in mind for the drug, but whatever it was, it didn't work, and MDMA went unused for most of the century. In the early 1980s, recreational use of the drug began to grow in the American South and Southwest. New users discovered a drug that could make them feel euphorically happy for as long as six hours--hence its street name--and increase their sensitivity to touch, taste, and smell. But in 1985, after researchers testified that Ecstasy caused brain damage in rats, it was outlawed by the Drug Enforcement Administration, which classified Ecstasy as a Schedule I controlled substance--the most restrictive designation, shared by heroin, PCP, and mescaline. Ecstasy migrated to Western Europe in the late 1980s, where it was most heavily and most publicly used by white teenagers at the intense, all-night dance parties that came to be known as raves.

During the early 1990s, raves started to migrate to the United States, where electronic music was becoming hot. Ecstasy migrated back along with them. It helped that the drug had good advance press--users billed it as a good, fun high, with no readily apparent downside. Those were Ecstasy's early days, when psychologists were still trumpeting the drug's potential as a therapeutic aid (those trumpets have since faded) and it was mostly discussed as part of the rave culture--a culture which psychologists and cops alike regarded with the bewildered, an-thropological interest of Stanley peering into the Congo for the first time. The ravers wore baggy clothes, they noted, and waved glowsticks, of all things, while dancing energetically for hours. The drug seemed to enhance users' sense of touch, and so members of the opposite sex seemed to touch each other a lot, they observed, and the young ladies tended to dress very provocatively indeed. The shrinks tended to think of Ecstasy as another what's-the-harm, makes-you-feel-better drug like marijuana. The cops were decidedly more skeptical.

"The scenes within the clubs were bizarre," a New Jersey investigator named Andrea Craparotta told Congress in 2000. "What I observed was shocking and many of the images were covertly captured on surveillance tape ... Unlike the thin, pale look of many heroin and crack cocaine users, Ecstasy users are primarily well-built, well-groomed, young adults with healthy outward appearances ... young adults would take Ecstasy and begin gyrating oddly to the pulsating `techno' music ... patrons would constantly touch one another, regardless of gender. Sex acts were often simulated on the dance floor." With horror stories like these (Simulated sex acts! Odd gyrations!), it's no wonder the authorities began to respond.

And as the drug's popularity began to grow, so did the federal government's interest in it. In 1991, the FDA permitted researchers to begin testing MDMA's effect on human subjects, and the National Institutes of Health funded research which concluded that Ecstasy had the potential to cause long-term damage to the brain's serotonin system, which helps to regulate sleep and mood. (Among scientists, this research was and continues to be deeply controversial, but the government and law enforcement have mostly accepted the serotonin-damage hypothesis as fact.) And as the drug's popularity grew throughout the 1990s, so did the attention and resources the DEA and other law enforcement agencies have devoted to it. In 1996, for the first time, the University of Michigan's Monitoring the Future study, a federally funded, comprehensive national survey that examines drug use among school-age children, added Ecstasy to its questionnaire. At that time, 6.1 percent of high school seniors reported having used the drug; five years later, that number had nearly doubled.

But it was the increase in Ecstasy traffic that finally caught the attention of Congress. In May 2000, Sen. Bob Graham (D-Fla.) sponsored the Ecstasy Anti-Proliferation Act, which brought federal penalties for Ecstasy possession into line with those for cocaine and heroin. The act cited a dramatic increase in traffic: the Customs Services had seized 500,000 tablets in 1997, and 4 million in the first five months of 2000, when the act was introduced. Grahams bill also galvanized state legislatures, many of which stiffened their own criminal penalties for trading and possessing Ecstasy in 2000 and 2001. Perhaps most importantly, it focused the efforts of the law enforcement community on Ecstasy. In October 2001, Sen. Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) told the Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control that Ecstasy was a "deadly drug" which was "targeting our youth." That same year, CNN claimed America was in the grip of an Ecstasy "epidemic."

All the Rave

So is Ecstasy really as dangerous as drug-enforcement authorities would have it? The answer is, probably not--at least in the short term. Unlike heroin or cocaine, the drug itself is not physically addictive, though rehab centers have begun to report an increase in the number of people seeking treatment for psychological dependence on Ecstasy. And while users of hallucinogens like acid or mushrooms sometimes have "bad trips"--a chemically induced state of acute panic--anecdotal evidence suggests that those who take Ecstasy rarely do. (Reliable numbers are extraordinarily difficult to come by, because most researchers seem to blame most Ecstasy-related bad trips on corrupted drugs, or other drugs passed off as Ecstasy.) And though long-term users seem to experience highs of declining intensity after dozens of uses, scientists who study the drug aren't sure why. In a few, extremely rare cases, and particularly when users have been dancing vigorously--a hallmark of the rave culture--Ecstasy seems to be linked to sudden heart attacks in healthy young people who do not appear otherwise disposed to heart failure. (This is also true of the widely available, over-the-counter supplement ephedrine.) In the case of Ecstasy, researchers have speculated that it somehow suppresses the body's ability to sense dramatic increases in its own temperature, leading the heart to over-pump and overheat the body; some also suspect that the deaths might be largely due to impure Ecstasy cut with amphetamines, which are known to increase users' heart rates. But ravers have adapted, learning to drink lots of fluids, which helps keep their body temperatures down--go to any rave today, and you'll see hundreds of teenagers dancing with bottles of water in one hand.

Then, too, each drug is its own best and worst advertisement, and Ecstasy sells itself pretty well. In the '70s, when crystal meth first popped up on the streets of San Francisco, everybody knew pretty quickly that this was dangerous stuff: there were all these bikers running around freaked out, prone to violence, and too hopped up to function normally. Similarly, the crack epidemic died down in the mid-'90s, police and drug policy analysts think, in large part because young people growing up in crack-ridden neighborhoods saw how devastating and unshakeable that drug could be. Like marijuana, Ecstasy's a much better advertisement for itself. For the most part, chronic users seem functional--they hold down jobs and stay in touch with family and friends.

What's still not clear, however, is the effects Ecstasy has over the long term. Scientists are undecided on whether chronic use causes permanent brain damage--and will probably remain so, since the drug has only been used recreationally for about 20 years, too brief a span for any meaningful long-term studies of lifetime users. "There's a very good chance that Ecstasy may turn out to be very harmless, something like marijuana, and I'm confident that it's not as dangerous to use as cocaine and heroin," Patrick Murphy, a professor of public policy and a drug policy researcher at the University of San Francisco, told me. "But there exists the possibility that chronic use could make people very, very depressed." What we don't know about long-term Ecstasy effects alone militates against outright legalization of the drug. But as it turns out, a determined, across-the-board effort to crack down on everyone who uses it might not be much better.

Down the Drug Supply Chain

Last spring, plainclothes detectives from a joint state and local force swarmed onto a foggy Camden, N.J., dock and pried open an orange metal cargo container that was supposed to hold fresh fruit. They found what they expected--about $3 million worth of cocaine and heroin and a couple of dozen automatic weapons--and arrested the gang members for whom the cargo was intended. But there was something else in there, stuffed alongside the powdered drugs: thousands of Ecstasy pills. "The Ecstasy was a surprise," said a spokesman for the Camden County District Attorney's Office.

It was a surprise because they hadn't thought that these sophisticated gangs were dealing Ecstasy. But it made sense. During the past two years, in parking lots along the Black Horse and White Horse Pikes--seamy commercial strips in South Jersey--they'd been picking up street dealers with Ecstasy as well as their traditional products, cocaine and heroin. Ecstasy, they realized, was inching its way down the supply chain for hardcore drugs. By the time the Office of National Drug Control Policy put out its monthly Pulse Check report last November, the trend--a more diverse user population, and a more professional caste of dealers--was showing up across the nation. Ecstasy was being sold along with crack, cocaine, and methamphetamines in Baltimore, Philadelphia, Denver, and Miami. Organized Ecstasy gangs were reported in cities as far-flung as Portland, Maine, and El Paso, Texas.

Ecstasy, it turns out, isn't a big profit center for dealers the way heroin and cocaine are, for the simple reason that it isn't addictive. The reason drug distributors have started to add it to their wares, suggests Rob MacCoun, a professor of public policy and law at the University of California-Berkeley, is that "they want to meet the diverse needs of their market"--customers ask for the drug, so the dealers feel they must provide it or risk losing those customers to more willing competitors. Yet when cut with amphetamines or other addictive drugs, Ecstasy becomes an ideal vehicle for hooking young people on the harder stuff.

The geography of Ecstasy has been changing, too. In New York, New Orleans, and Washington, D.C., reported the ONDCP, Ecstasy was most frequently being bought in inner-city ghettos rather than suburban raves. Most ominously, its sales were moving outdoors--a leading indicator for the kind of gang violence and street-corner shootouts that have devastated so many poor neighborhoods during the crack epidemic. Once a dealer begins selling his drugs in a public place to people he doesn't know, he becomes a prime target for robbery. To protect himself, he carries a gun--and so the thieves do, too. "A street market for any expensive drug is going to be enormously disruptive to the community," Kleiman said. "This is where MDMA can get scary."

Gateway High

So Ecstasy presents a novel dilemma. Until recently, it's been a drug that is relatively safe, popular among teenagers, and distributed mainly by nonviolent amateur dealers who sell the pure, non-addictive version of the drug. But it is becoming a drug controlled by violent, professional drug traffickers, who routinely mix the drug with more dangerous, addictive--and, hence, profitable--substances, and who aim to convert today's Ecstasy users into tomorrow's crackheads, to turn Ecstasy into what it has not yet become: A gateway drug.

The challenge for policymakers, then, is to break the connection that's now being made between Ecstasy users and organized drug dealers, before it becomes a full-fledged street drug with an attendant culture of violence and addiction. And that means distinguishing between the kind of large-scale distribution that will destroy neighborhoods and lives, and the small-scale culture of social Ecstasy use and informal dealing that probably won't. Ecstasy should be illegal. But what's needed is an enforcement regime that keeps teenagers who do use it away from street gangs.

Unfortunately, current policy is trending in exactly the opposite direction. Undercover operations, for instance, now focus heavily on raves, primarily targeting users and casual dealers rather than large-scale distributors. In California, legislators introduced a bill last year that would make it harder for rave promoters to get permits, and make them civilly liable for any injury suffered by anyone high on drugs at their parties. In Congress, Sens. Joe Biden (D-Del.) and Charles Grassley (R-Iowa) crafted a bill making the promoters criminally liable for drug use in much the same way that people who own crack houses are. The bill was tabled at the end of last year, but passed in April, after being tucked into popular legislation to create an "Amber Alert" system. Meanwhile, district attorneys from Chicago to New Orleans have been prosecuting rave promoters under local laws originally passed to target owners of crack houses.

The laws are not only unfair--if someone buys a pill of Ecstasy at a bar, runs into a pole, and puts himself in a wheelchair, his parents don't get to sue the bar owner--but counterproductive. And at best, it will make buying Ecstasy at a rave no less risky than buying it on the street, from dealers looking to get them hooked on coke; at worst, the new legislation will focus law enforcement efforts disproportionately on raves, actively driving users into the arms of hardcore street dealers.

The same societally destructive incentives are increasingly being built into legal penalties for Ecstasy use and sale. The federal sentence for anyone possessing more than 8,000 Ecstasy pills now is a mandatory minimum of 10 years. This makes sense; no casual user or amateur dealer would have 8,000 pills on hand. (If you were to take a new pill each time your last high ended--which nobody does--it would take you more than five years to use up 8,000 pills.) Federal law, and most state and local laws, also mandate quite modest penalties for possession of small amounts of the drug--many states, like Delaware and Minnesota, match possession penalties for Ecstasy with those for marijuana, and allow judges to punish violators with simple fine. This, too, makes sense. Ecstasy simply isn't as dangerous as drugs like crack. Because the uncut Ecstasy traded among ravers is not physically addictive, it's not likely to create populations of prostitutes and thieves who commit crimes to feed their habit. Nor do the drug's users die from overdosing, as users of cocaine and heroin often do. Moreover, the rapid growth of Ecstasy use has recently tapered off.

Yet despite all this, state and local elected officials are pushing to stiffen penalties for possessing or selling small amounts of Ecstasy to bring them in line with drugs like methamphetamines, and, to a slightly lesser extent, heroin and cocaine. Simple possession in Georgia means a mandatory minimum of two years in prison. A failed 2001 bill in Illinois threatened a mandatory minimum of six years in jail for possession of 15 tablets of Ecstasy. And Texas mandates two years in jail for anyone caught with one gram of Ecstasy or more (one gram is equivalent to about four pills). Such high penalties, if they become common, will not only fill the nation's prisons with non-violent Ecstasy users. They will also drive frightened amateur rave dealers out of business, with both positive and negative consequences. On the plus side, fewer dealers at raves should lead to less Ecstasy consumption among casual users. On the minus side, it will almost certainly drive the more determined young users toward the serious traffickers, where more addictive drugs and other dangers await.

What's needed, instead, is a two-tracked policy. Penalties and enforcement should be extremely tough on high-volume traffickers and their street-level dealers, with much lower penalties for, and less enforcement against, users and amateurs who peddle small quantities of the drug to friends and acquaintances. Instead of cracking down on raves, law enforcement should recognize that rave-based Ecstasy use will be relatively safe, especially if they tolerate the presence of testing organizations that can help ensure that users don't move on to other drugs (see sidebar). The model here is the Dutch program of allowing users to smoke pot in licensed cannabis shops. Dutch lawmakers saw that whereas cannabis use in itself was relatively benign, dangers emerged when cannabis users bought from dealers who also sold cocaine, heroin, and other hard drugs, which thrust them into a more violent drug market and exposed them to addiction. The Dutch policy has been moderately successful in keeping pot smokers away from hard drugs, according to Berkeley's MacCoun and Peter Reuter of the University of Maryland. Only 22 percent of marijuana users in Holland report having tried cocaine; 33 percent of American pot smokers say they have. (Heroin use among pot smokers in America and Holland is statistically identical). "It's an approach which we haven't been willing to consider in America--separating the users from the real harm," MacCoun said. Raves could play a similar role for Ecstasy, containing use of the drug and keeping teenagers out of the orbit of street dealers. That wouldn't necessitate making Ecstasy legal. But it would require an attitudinal shift: Legislators and police officials would have to focus on reducing the harm caused by Ecstasy, and not simply on reducing the number of users.

Crime and Punishment

It's true, of course, that having an Ecstasy strategy that punishes low-level users and dealers far less harshly than large-scale distributors will inevitably raise charges of racism. Why should prosecutors and police let suburban white kids who do the drugs at raves and deal to their friends slide by, while cracking down harshly on criminal gangs typically led by immigrants, blacks, and Hispanics? For the simple reason that some dealers are a clear threat to the communities in which they traffic, and others are not. The sentencing disparities between cocaine and crack, for instance, are deeply unjust, putting many-fold more blacks than whites behind bars for consuming or selling what is in essence the same chemical. Yet most opponents of this injustice concede that there should be at least somewhat stiffer penalties for crack, because that form of the drug is simply more destructive to users, neighborhoods, and society generally. Moreover, a two-track penalty scheme for Ecstasy would mean relatively light treatment for all users regardless of their color. Only the big drug traffickers and their dealers would suffer.

This makes sense. I've seen this distinction while covering the Ecstasy debate: Some drug dealers carry automatic weapons, and others lose their socks. Nine months ago I interviewed Andrew, a 17-year-old user and low-level dealer from South Jersey who'd been busted by an undercover cop. The judge in Andrew's case took pity on him and sentenced him to a rehab clinic; I met him at a coffee shop after he'd been released, last fall. He was 20 minutes late and apologized; he'd wanted to be on time but then he couldn't find clean socks. I asked him when he'd started dealing and why, and he wasn't sure. For Andrew, as for many Ecstasy users, there was a substantial gray area between using and dealing--if you give your buddy a pill, and he lets you crash at his place for a night in return and buys you dinner, are you a dealer? Andrew asked me about applying to colleges; he said he wanted to major in business. I knew someone in admissions at Dartmouth, I told him, a little helplessly. If he applied, maybe I could put in a good word. The judge had been right: Andrew clearly belonged in rehab, not in prison; he needed to be given a good primer on life, perhaps an undergraduate course catalogue, and probably a hug. Putting a guy like this in prison for five years would be deeply destructive--both to him and to society.

Safety Dance

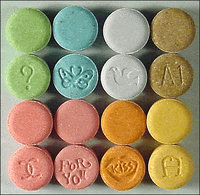

ANOTHER PROBLEM WITH THE new anti-rave laws is the effort to crack down on volunteer groups which test ecstasy for purity at raves. San Francisco-based DanceSafe, for instance, does most of its work by mail: Users send in pills from dealers who claim to be selling Ecstasy, and for no charge, DanceSafe tests the chemical composition of the pills and posts the results on its Web site. The results can be eye-opening: Many of the pills have no MDMA in them at all, and some are cut with dangerous, addictive uppers like codeine or methamphetamines. Cops and legislators who specialize in club drugs know about DanceSafe, and when they're arguing for stiffer penalties against dealers, they cite DanceSafe's tests to show that dealers frequently change their product's chemistry to make it more addictive, and dangerous.

But these same legislators and cops are reluctant to allow those same tests to ensure Ecstasy is safe for users. These testing organizations would like to operate mobile testing facilities at raves--so that rather than the weeks-long lag of sending pills to San Francisco and waiting for the tests to come back--users can know right away whether their pills are safe. But cops refuse to let these organizations operate at raves, out of an understandable fear that they would be tacitly endorsing drug use. The current effort by prosecutors attempting to make rave promoters civilly and criminally liable for drug dealing would for all practical purposes prohibit on-site testing: If a rave promoter tolerates drug testing at his events, it will be very difficult for him to argue in court that he wasn't aware drugs were used at his raves.

But instead of keeping kids safe from drugs, banning testing organizations might just do the opposite. While Ecstasy isn't itself addictive, most experts agree that the likelihood of Ecstasy users taking up other drugs will only increase as street dealers take over the market, cutting Ecstasy or selling it along with other, addictive drugs. "Pure" Ecstasy won't turn you into an addict. But if your MDMA is cut with crystal meth, you're more likely to go back for more. And if your dealer sells cocaine, too, you're more likely to try the new drug than a user who otherwise might not know where to get it. So legislators and cops alike ought to be friendly towards non-profit testing groups which can help to guarantee the purity--and consequently the safety--of the Ecstasy sold at raves. Local governments themselves do not need to operate testing stations. But they should be encouraged to permit Ecstasy testing at raves as a concession to public health--which is, incidentally, very similar to how needle-exchange programs work.

BENJAMIN WALLACE-WELLS is a reporter for The Philadelphia Inquirer.

COPYRIGHT 2003 Washington Monthly Company

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group