The first U.S.-approved tests on the therapeutic effects of MDMA, the active chemical in the "nightclub drug" known as ecstasy, may begin in a few months, 17 years after it was made illegal and 90 years after it was invented. At issue is whether this powerful neurotoxin can be an effective tool for therapy. What is certain is that scientists know as much about MDMA's long-term effects on the brain as they do about most commonly prescribed psychotropics -- that is, very little.

A recent Fox News special on the lasting effects of ecstasy had a psychiatrist from Emory University in Atlanta displaying before-and-after slides of an ecstasy user's brain. He claimed the slides demonstrated lasting damage. But when questioned by INSIGHT, the expert knew neither whose research he had presented nor details of the alleged tests. Misinformation and mythology, critics say, are as common in the war on drugs as in the mental-health community.

Many drugs have unintended side effects, but while TV commercials quietly tag on messages that say a pill might cause heart problems or that pregnant women should not handle them, these warnings pale in comparison to the potential dangers of mood-altering drugs. Here are a few side effects of one psychotropic: paralysis, coma, hysteria, suicidal idealization and violent behaviors, arrhythmia, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, ulcers, colitis, hepatitis, incontinence, gout, goiter, hyperthyroidism, eczema, psoriasis, osteoporosis, abortion, glaucoma, deafness, taste loss and sexual dysfunction.

That drug is Prozac, the most widely prescribed pharmaceutical in the country. And though its mood-altering chemical compound has been used by millions, little is reported about its potentially deadly side effects. Its manufacturers get by with claims that the effects listed above are rare, occurring in less than one in 1,000 users. But, as INSIGHT has reported, psychotropics often have been linked with cases in which people have been involved in bizarre and deadly incidents.

Prozac, as well as Paxil and Zoloft, are serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) that increasingly have been prescribed for depression. Serotonin, a neurotransmitter, is a chemical that facilitates communication within the brain. It is contended that serotonin allows one to experience happiness when it is released into the synapses, the empty spaces between nerve cells. Antidepressants are supposed to prevent the reabsorption of serotonin so that the "happiness experience" can last longer.

If so, people for whom SSRIs are prescribed should have lower levels of serotonin than happy people. But there is little evidence of this. "The categories of mental illness are so porous as to allow everyday unhappiness to pass into the category of a more significant disease," says Ronald Dworkin, a physician at the Hudson Institute in Indianapolis. The way these psychotropics affect the emotions is more mysterious, and more threatening, than practitioners who use them have dared to admit.

It nonetheless has become increasingly common to prescribe these drugs to people suffering from milder forms of depression. As Kelly Patricia O'Meara reported in INSIGHT (see "Doping Kids," June 28, 1999), "six million children in the United States between the ages of 6 and 18 are taking mind-altering drugs."

Dworkin and others argue against use of psychotropics altogether. But some suggest the point is not that Prozac and other psychotropics never are beneficial, but that often they are administered as take-home solutions rather than in conjunction with therapy and careful observation. And, even when SSRIs are being used in therapy, they may be doing more than "freeing" the mind. No one knows what damage may be done to the brain by a lifetime of psychotropic treatment.

But now some doctors are hoping to use ecstasy on their patients.

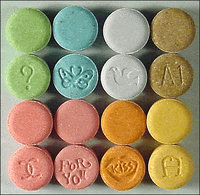

This may not be as strange as it seems. Before the drug was banned in the mid-1980s, doctors claimed to have been using it in therapy with success. Some patients reported overnight breakthroughs and couples treated together solved long-term issues. Its advocates claim the reason the drug was made illegal, and remains so, is its rampant abuse at nightclubs.

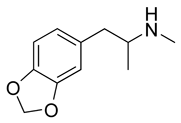

In some ways MDMA is very different from SSRIs. Instead of just affecting serotonin, it floods neurons with several neurotransmitters, including dopamine and noradrenaline. And, unlike Prozac, MDMA appears to reduce depression, anxiety and other emotional ailments immediately.

Rick Doblin is the president of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), an organization dedicated to MDMA research. On Nov. 2, 2001, MAPS was the first group to receive Food and Drug Administration approval for therapeutic MDMA research. Doblin hopes this research will begin in a few months, after he receives approval from the University of South Carolina's Institutional Review Board. He discussed some of the misconceptions about the drug with INSIGHT.

Doblin estimates that for roughly every 2 million users of ecstasy there is one directly related death. And, as a designer drug, ecstasy often is cut with sometimes-deadly substances that he thinks are responsible for a majority of related deaths. Though, contrary to the urban myth, he says, heroin is rarely if ever used to cut the drug. And Doblin believes concern about ecstasy deaths should not deter approval of research. The most common MDMA-related deaths, he says, are from overheating or overhydration. "In the temperature-controlled environment of therapy, where a patient will be drinking a regimented quantity of water, one does not run that risk," Doblin claims.

No one ever has died in MDMA therapy, and scattered research abroad suggests it may prove helpful in relieving certain acute stress. Doblin specifically cites MDMA research on Tape victims in Spain that has not yet been published. The U.S. research would focus on male and female victims of criminal and sexual abuse. An Israeli study will focus on victims of war and terrorism. Eventually Doblin hopes to test MDMA as a direct competitor against psychotropics. "So this may be why companies haven't jumped on the bandwagon," he says.

Doblin knows there are a few other reasons, too. For one, selling MDMA is not a marketer's dream. Not only does it have a bad image, but the patent has run out, so no company would have an opportunity for the enormous profits of, say, Prozac or Zoloft.

Also, as noted, MDMA is not meant as a take-home drug. While most SSRIs are taken daily by users, MDMA would be used under strict control and in small doses during limited therapy sessions over a lifetime. So MDMA lacks both the potential for harm and the enormous profitability of the standard psychotropic -- unless, of course, it is abused as a street drug.

Doblin admits that he does worry about the widespread medicating of society with psychotropics and other drugs. "It is a double-edged sword," he says. He rejects unauthorized medication. In uncontrolled settings, MDMA is famous for having triggered anxiety attacks and psychotic breakdowns. People on ecstasy have experienced severe depressive periods that have sent some to hospitals begging for tranquilizers. The drug's proponents are aware of this. They respond that, under proper controls, MDMA frees people to experience emotions and memories they otherwise were unable to confront -- and that without therapy they are left to face them on their own. "A person in therapy is prepared to do serious introspection. Someone else may not be," Doblin says.

The trouble is that studies conducted by neurologist George Ricaurte of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine associate serotonin depletion and brain damage with use of MDMA. Ricaurte studied ecstasy users from the standard population (who also may have used other drugs). Their serotonin levels were compared with those of drug-free students, as though they should have been the same. Serotonin levels were lower amongst drug users. But in a Swiss study, the opposite results were found when testing individuals before and after ecstasy use, although studies have disagreed on what counts as "use" and "abuse."

But the most serious concern is that MDMA may cause brain damage -- may, in fact, be a neurotoxin.

When the brain is damaged, neural pathways often become misshapen. In a study on monkeys performed by Ricaurte this did not occur, but the neural pathways bundled up and reorganized, suggesting changes. Those changes were interpreted as damage by some, though unlike Prozac or Ritalin, high levels of MDMA have not been found to cause starlike lesions in neural pathways. James O'Callaghan, a neurotoxicologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has addressed this inconsistency in the pharmacological community, calling it a "double standard."

While long-term effects of psychotropics are dubious, less tenuous are the links between these drugs and horrific psychotic episodes, sometimes associated with high-profile killings (see "A Different Kind of Drug War," Dec. 13, 1999). Experts readily admit their ignorance concerning lasting impact of psychotropics on the brain, but they downplay or ignore what is known about their immediate and troubling effects.

BRANDON SPUN IS A REPORTER FOR Insight.

COPYRIGHT 2002 News World Communications, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2002 Gale Group