A 39-year-old female attorney came to the office for an evaluation of long-standing hoarseness (since childhood). She said she felt as though she needed to strain her voice in order to talk, and she complained of vocal fatigue, especially with prolonged speaking. She said that her voice had "never been normal." Even so, she had never had her voice or larynx evaluated prior to our examination.

The woman had been born via a normal vaginal delivery without the use of forceps, and she had no congenital disorders. She had experienced no significant medical illnesses or hospitalizations during her infancy and childhood. She had taken singing lessons for 6 months when she was 15 years old, but she had never received any formal speech therapy. As an adult, she described herself as a nonsinger.

The patient denied odynophonia, dysphagia, odynophagia, throat tickle, chronic cough, chronic throat clearing, and heartburn. Her medical history included mild asthma as a child and a 7-year history of ocular migraines. She had had two pregnancies, both of which culminated in cesarean sections; during one of them, she delivered fraternal twins. Her surgical history included an abdominoplasty. She was allergic to penicillin, she was not taking any medications, and she denied the use of alcohol, tobacco, and recreational drugs.

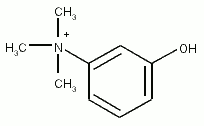

On examination, her voice was slightly hoarse and slightly breathy. Strobovideolaryngoscopy revealed several laryngeal abnormalities. There was a moderate degree of supraglottic hyperfunction that improved slightly with a voluntary increase in pitch. Abduction was normal bilaterally, but adduction was slightly sluggish on the right and variable on the left. Longitudinal tension was variably sluggish on both sides. The arytenoids and posterior laryngeal mucosa were normal. At the midpoint of the vibratory margin of the left vocal fold, there was a broad-based, ill-defined, fibrotic, posthemorrhagic, vascularized mass (figure 1). There was diffuse stiffness at its base that resulted in a moderately decreased mucosal wave amplitude and waveform in the middle and posterior thirds of the musculomembranous vocal fold. On the right vocal fold, there was a softer, polypoid mass that featured an area of ectasia (figure 2). This mass was also centered in the striking zone, slightly anterior to the mass on the left voca l fold. The mucosal wave on the right was mildly decreased in amplitude and waveform in the middle third of the musculomembranous vocal fold.

The variability in vocal fold mobility was consistent with bilateral paresis, neuromuscular junction dysfunction, or compensatory hyperfunction in response to unilateral paresis. Laryngeal electromyography showed a 20% decreased recruitment response in the left cricothy-roid muscle, which did not improve with Tensilon (edrophonium chloride) testing. These findings were consistent with a left superior laryngeal nerve paresis with compensatory hyperfunction.

The patient underwent voice therapy to strengthen the paretic muscle group and to relieve the compensatory muscle-tension dysphonia. She was happy with her post-therapy voice results. Resection of the vocal fold masses was not performed, and it will be considered only if the patient again becomes dissatisfied with her voice.

From University of Illinois at Chicago (Dr. (Heman-Ackah), Thomas Jefferson Hospital (Ms. Cooney), and the Department of Otolaryngology--Head and Neck Surgery, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia (Dr. Sataloff).

COPYRIGHT 2002 Medquest Communications, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2002 Gale Group