LEARN NOW THIS MUSCULAR DISEASE WEAKENS YOUR PATIENT AND WHAT YOU CAN DO TO HELP HER.

"Have you ever cared for a patient with myasthenia gravis?" the neurologist asked as I sat in his office. I stared at him in disbelief. I was 24 years old.

Months before, I'd begun to notice strange changes in my body. While washing my hair, shampoo would burn my eyes because I couldn't close them tightly. Simple tasks became more difficult: My arm would tire when I held the blow-dryer. I'd lost the ability to whistle, and sometimes my speech became slurred, especially if I'd been talking a long time. At dinner one evening, I tried to drink some water and it ran out of my nose.

When I couldn't ignore the symptoms any longer, I saw my primary care provider. He performed a complete examination and quickly referred me to the neurologist. Now I couldn't believe what I was hearing.

A "grave weakness"

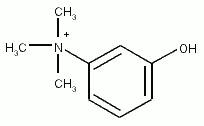

The term myasthenia gravis comes from Greek and Latin words meaning "grave muscle weakness." An autoimmune disease that weakens the voluntary muscles, it's chronic and progressive. It doesn't affect the involuntary heart muscle or smooth muscles of the blood vessels, gut, and uterus. The weakness of myasthenia gravis occurs because antibodies bind to and degrade acetylcholine (ACh) receptors on the muscle surface. Having fewer receptors impairs the nerve's ability to contract the muscle. The weakness increases with repetitive stimulation and improves with rest.

The clinical course of myasthenia gravis varies and is often affected by recurrent illness, emotions, and medications. (See Drugs to Watch Out For.) Weakness can be confined to specific muscle groups, such as those that control the eyes, or progress to generalized weakness. Ptosis and diplopia may be the patient's first symptoms. Her facial expressions and her speech may change. Chewing and swallowing may be difficult. She may also have difficulty with fine motor tasks, such as writing, or tire when she raises her arms above her head.

The most serious effect of myasthenia gravis is weakness of the intercostal muscles and the diaphragm. Breathless and unable to cough and clear secretions, the. patient may develop respiratory distress and require ventilator support. A sudden exacerbation of symptoms with respiratory failure is known as myasthenic crisis.

Myasthenia gravis affects both sexes and all races and ages. The peak incidence is between ages 20 and 30, with women more commonly affected at a younger age. The Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America estimates that the disease affects 14 of every 100,000 Americans, but the prevalence could be much higher because diagnosis is difficult.

To pinpoint the diagnosis, the physician performs a thorough neurologic examination, a complete history, and a Tensilon (edrophonium chloride) test. Injected intravenously, Tensilon significantly improves muscle weakness within 60 seconds and sustains improvement for up to 5 minutes. Only the weakness of myasthenia gravis reverses dramatically after Tensilon. My diagnosis was clear-cut because my Tensilon test was positive.

Up to 90% of patients with myasthenia gravis have an elevated ACh receptor antibody titer. The physician may order electrodiagnostic testing, such as repetitive nerve stimulation, to identify the defect at the myoneural-junction, but testing can be uncomfortable and the results difficult to interpret.

Getting aggressive

No cure is available for myasthenia gravis, but aggressive treatment with the following options can help the patient lead a near-normal life.

* Thymectomy. Approximately 75% to 80% of patients with myasthenia gravis have hyperplasia of the thymus gland; another 15% have thymic tumors. Although the thymus is involved in development of the immune system, its exact role in myasthenia gravis is unknown. However, research has shown that more than half of patients who have a thymectomy improve, probably because production of antibodies that target ACh receptors stops.

Females under age 30 who have surgery within 2 years of diagnosis generally have the best outcomes, but some older and long-standing patients also benefit. Improvement after surgery can take up to 2 years.

* Anticholinesterase therapy. Drugs such as pyridostigmine (Mestinon) and neostigmine (Prostigmin) are commonly used to inhibit the antibodies that cause myasthenia gravis. The goal of therapy is to maximize the patient's muscle strength with few adverse reactions, which include gastrointestinal upset, bradycardia or tachycardia, hypotension, and visual disturbances. Anticholinesterase drugs typically aren't effective during the first 48 hours of a myasthenic crisis, so a patient in crisis needs physical and emotional support.

Toxic amounts of anticholinesterase drugs can trigger a cholinergic crisis. (See Which Crisis Is Which? to find out how they differ.) Serious unwanted responses include bronchospasm, respiratory or cardiac arrest, and increased secretions. Teach your patient to seek medical attention right away if she has trouble breathing or swallowing after taking her medication. She should also have the antidote, atropine, readily available as advised by her physician.

* Corticosteroids. A corticosteroid such as prednisone may inhibit antibody production related to myasthenia gravis. However, therapy carries a high risk of unwanted responses, such as mood changes, weight gain, and susceptibility to diabetes and osteoporosis, so your patient needs careful monitoring while taking it. Her weakness may increase temporarily when she first starts therapy, and the drug's effects on her immune system may inhibit her natural ability to fight off infection. To get the desired effect and minimize adverse reactions, the physician may prescribe alternate-day dosing.

* Immunosuppressants. Drugs such as azathioprine or cyclosporine may suppress the immune stimulus for ACh receptor antibody production. The receptors can then regenerate, regain neuromuscular function, and restore muscle strength. The benefits of immunosuppressant therapy must be weighed against the risk of infection.

* Plasmapheresis. In severe cases of myasthenia gravis or when the patient's muscle strength declines rapidly, plasmapheresis may be used to remove ACh receptor antibodies. During the procedure, the patient's blood plasma is separated from the cells and replaced with fresh frozen plasma and albumin. The exchange takes 3 to 4 hours and is generally done three times a week.

What you can do

A patient with myasthenia gravis receives outpatient care unless she's undergoing surgery or in crisis. (See How to Help a Patient in Crisis.) Whatever the reason for her admission, closely monitor her respiratory status. Teach and encourage her to use an incentive spirometer and perform frequent coughing and deep-breathing exercises to reduce complications.

Your patient may be embarrassed about her condition and try to cover it up. Encourage her to talk about her problems and, if possible, put her in touch with someone who has the disease and has responded well to treatment. The Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America provides English and Spanish teaching materials and can give her health alert cards and information on getting low-cost medications.

Support is key

I was fortunate to have supportive family and friends to help me over difficult times with myasthenia gravis. You can become an advocate for your patient by knowing more about this disease and the available treatments. Arming her with knowledge and support can increase her coping skills and empower her to take control of her disease.

SELECTED REFERENCES

Hickey, J., and Minton, M.: "Neuroscience Nursing for a New Millennium," Nursing Clinics of North America. 34(3):541-554, September 1999.

Keesey, J., and Sonshine, R.: A Practical Guide to Myasthenia Gravis, 2000. http://www.myasthenia.org.

Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America: Informational Services, 2001. http//www.myasthenia.org.

Cathy Yee is a cardiac patient-care specialist at Providence Holy Cross Medical Center in Mission Hills, Calif.

Copyright Springhouse Corporation Jan 2002

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved