Three different experimental drugs that inhibit HIV by the same mechanism (blocking its use of the CCR5 co-receptor) have run into problems recently in clinical trials. But the problems are very different.

CCR5 is a protein on the surface of human cells that most HIV uses to help it enter the cell (some HIV uses a different protein instead, usually CXCR4). A few people have no CCR5 (due to an inherited mutation); they appear to be in good health, and are very unlikely to be infected with HIV. Therefore scientists have looked for CCR5 antagonists--drugs that could bind to CCR5 and prevent HIV that uses CCR5 from entering cells.

Two risks with this treatment approach are that the CCR5 may turn out to be necessary for some people for unknown reasons--or that when HIV is prevented from using CCR5, it might evolve within an individual patient to use CXCR4 instead. At this time no one knows if either of these will be a problem.

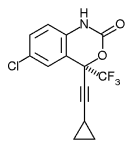

Three CCR5 entry inhibitors have recently been in large clinical trials: aplaviroc from GlaxoSmithKline, maraviroc from Pfizer, and vicriviroc from Schering Plough.

Here is the basic situation (early December 2005).

Aplaviroc: On October 25, 2005, GlaxoSmithKline announced that it was stopping enrollment in its phase III trials after potentially serious liver toxicity had been found in several patients in this and other trials. Patients already in the phase III trial will be allowed to continue under careful monitoring until other plans can be made, if their physician believes they are benefiting from the drug, but Glaxo's intent is to have all patients stop therapy with aplaviroc.

Maraviroc: One patient of more than one thousand who have received maraviroc developed serious liver toxicity. Currently no one knows if maraviroc contributed to the problem, because this patient had other risk factors and had elevations of liver enzymes before starting the drug. Only five doses of maraviroc were taken (the liver problems with aplaviroc took much longer to develop). The DSMB (Data Safety Monitoring Board) analyzed the trials in July and late September and recommended no changes. It met on an ad-hoc basis to analyze this case, and recommended several changes to study eligibility criteria and safety monitoring, which are now being implemented. The DSMB will next meet as scheduled in January.

Vicriviroc: Schering-Plough and the ACTG stopped low-dose arms in their trials, and later Schering-Plough stopped its treatment-naive trial entirely, because the volunteers receiving vicriviroc plus Combivir were not controlling the virus as well as those in a comparison arm receiving efavirenz plus Combivir. Trials for antiretroviral-experienced volunteers are continuing (see http://www.clinicaltrials.gov--search for "vicriviroc"). We have not heard of liver toxicity or other safety problems.

The FDA, working with the Forum for Collaborative HIV Research, had set a public meeting in January on long-term followup of patients enrolled in these trials. On December 1 the FDA announced that this meeting, the FDA/FCHR Collaborative Meeting on Long-Term Safety Concerns Associated with CCR5 Antagonist Development, would be postponed until February or March, in order to wait for more information. Comments will be accepted until January 15 at http://www.hivforum.org/CCR5/index.html

Comment

The above information does not suggest a "class effect"--that blocking CCR5 itself will cause problems, no matter what drug is used to do so. However, no one knows why natural selection has led to over 99% of people having CCR5--but with the others having no obvious ill health as a result. Some published research has suggested that removing CCR5 in animals, while not causing problems just by itself, can make certain other problems more serious. All this is guesswork until more information is available.

We are concerned that due to recent waves of publicity and lawsuits about the dangers of other, non-HIV drugs, companies may be too ready to abandon experimental treatments if problems develop. The alternative is to see if it is possible to manage problems that may affect very few patients--by detecting them early enough to prevent harm, or better yet, by learning the mechanisms of toxicity well enough to predict who is likely to be vulnerable, so that they will never take the drug but use other treatment options instead. Such practical, focused medical research could have spin-off benefits for treating other diseases as well.

The problem is that neither academic nor pharmaceutical research groups are in a particularly good position to do this work, given how U.S. industry is organized today. Some team or teams would need to specialize in such investigations, probably for a number of different drugs, and find modest but long-term funding to do so. Dealing with "rights" to the various chemicals and research tools owned by many different parties could also be a serious obstacle to producing useful results.

COPYRIGHT 2005 John S. James

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group