Linda Brooks had tried to deal with her daughter Laura's erratic behavior in a way that didn't involve medication, but she was running out of options. Laura, 11, was always "acting out," Brooks says, jumping out of her seat in class, interrupting teachers, not finishing assignments. She'd had similar problems at other schools--the one she currently attends is her sixth since pre-K. At home she would talk back constantly and butt in on grown folks' conversations. Her room was a disaster area, and when Morn said to clean it, "she'd shove everything under the bed and into drawers and the closet."

So last December, after years of resistance, Brooks, who is a single morn and works as a FedEx carrier in Houston, agreed to put her bright, spirited daughter on medication. Laura has started taking Adderall, a stimulant, for symptoms of attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD. (Stimulants increase brain activity, increasing alertness and attentiveness.) Since her daughter has been on the medication, Brooks says, her behavior has done a 180-degree turn. She finishes assignments, stays in her seat, and follows directions. She's gone from D's to B's and straight E's--for excellent--in conduct. At home she minds her mother and cleans her room.

With estimates that between 3 percent and 5 percent of children nationwide--about 2 million--have ADHD, one of the most common mental-health diagnoses among children today, stories like Laura's are not unusual. Among Black parents, though, suspicions of bias and fear of stigma exacerbate an already complicated situation. Although the estimated rates of ADHD are the same for Black children as for children nationwide, experts say a distrust of pharmaceuticals and the medical profession often makes us leery of medicating our children when behavior issues arise.

Of course, part of the problem is an educational system that expects children to stay still for 45 minutes at a time and comply rather than challenge. "Most kids don't need medication," says Jawanza Kunjufu, an education consultant and author of Keeping Black Boys out of Special Education (African American Images). "Boys need to be at the front of the class, where they can focus. They need lesson plans that embrace their culture. They need movement and physical education put back into the curriculum." But until we retool our schools, parents must try to fit their children into the existing systems.

Dan Johnson, for one, is trying everything he can to keep his smart, energetic son, Christian, now 8, off "the stuff," as he calls it. Like Laura, Christian has struggled at school and at home. After he was expelled from school, he was diagnosed with ADHD and meds were recommended. Johnson, a business and church consultant in Chicago, reluctantly agreed to allow Christian, then 5, to try a prescribed stimulant. His behavior improved, but Johnson, who says he grew up seeing how illicit drugs affected some of his close family members, remained skeptical. So when Christian cried out one day in class that he couldn't be a good boy without his medication, his dad discontinued the drug and switched him to an herbal supplement (see sidebar, next page). Though tolerable, Christian's behavior was less consistent after the change.

So who's right? Must our kids be medicated to succeed?

A HEATED DEBATE

Using prescription drugs to reduce inappropriate behavior in children has certainly become more acceptable. Research shows a surge in the last 15 years in the number of children taking powerful medications like Ritalin. Sales of methylphenidates, like Ritalin, classified by the federal Drug Enforcement Administration as controlled substances because of their addictive potential, increased nearly 500 percent from 1991 to 1999. Sales of amphetamines like Adderall rose more than 2,000 percent in that time.

Still, some experts argue that children are often labeled ADHD when other problems exist. Some even deny that such a "disorder" exists. One study suggested that "agitation syndrome," or environmental stress, not attention deficit, may be affecting adolescent Black boys. Meanwhile, the National Medical Association, a group of doctors of African descent, recently sounded the alarm that the rise in hyperactivity-disorder diagnoses has led to disproportionate numbers of Black children in special education. Blacks make up 12 percent of the population but 28 percent of special-ed students.

While many African-Americans believe our kids are misdiagnosed with ADHD, the reality, mental-health practitioners say, is that many Black children lack access to proper screening by adequately trained health professionals. The result: Our children are vilified and criminalized for behavior that, when exhibited by White children, prompts calls for treatment and support. "While their White counterparts are seen as having mental-health needs, Black children are seen as acting up and labeled bad," says Annelle B. Primm, M.D., M.P.H., an associate professor of psychiatry at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

Primm says we can't begin to address the problem until we first overcome our own biases. "We need to shift the discussion from concern over our children being drugged to how our children are being treated," she says. "Let's be sure our kids get the attention they need and aren't shunted into the direction of the juvenile justice system, because you know what that means for our community."

MOVING BEYOND THE STIGMA

If your child has behavior issues in school and you're not sure why, take steps to discover the root causes and get help:

Ask questions. If the teacher complains that your child consistently has trouble focusing and has a hard time sitting still, find out why. Get a complete educational, psychological and neuropsychological evaluation done by a trained mental-health professional, particularly one who understands our culture. Mental-health practitioners are more likely to run the full battery of evaluations to make their assessments. Prices vary, and insurance may not cover the cost, so it's best to shop around. Ask your pediatrician for a referral, or identify a local mental-health-care clinic.

Know your rights. A teacher can't "diagnose" a child, but she can share her observations with the child's evaluator. Also understand that in most states it's not illegal for a school to require a student to take medication in order to attend; many schools may even say that they are "not equipped" to teach certain children. (If this happens to you, contact the Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates [copaa.org] for help.)

Consider alternative approaches. If your child is diagnosed with ADHD, be aware that you have options. Studies show that a combination of drugs and therapy works better than drugs alone or therapy alone. In behavior therapy, children learn strategies to help them focus, control their behavior, and respond appropriately when they're frustrated or anxious. Many doctors also recommend exercise and changes in diet and lifestyle, as some research has linked food allergies and excessive television watching to the disorder.

Defining Behavioral Disorders

Unsure of the difference between ADHD, ADD, ODD and CD? This guide will help:

* ADHD and ADD are often used interchangeably, although ADD refers specifically to attention-deficit disorder without hyperactivity. Common features of ADHD include distractability, impulsivity and hyperactivity. Some studies indicate that boys are diagnosed with ADHD more often than girls by a ratio of 10 to 1.

* ODD, opposition defiant disorder, refers to a child who is often defiant, stubborn, noncompliant or belligerent. Some children are diagnosed as having ADHD and ODD.

* CD, conduct disorder, is defined as a serious pattern of antisocial behavior, such as fighting, bullying, lying or stealing. A troubling trend, notes Annelle B. Primm, M.D., of Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, is the growing popularity of this diagnosis for Black children. "Conduct disorder is usually indicative of something else the clinician should look for," she says. If your child is diagnosed as having CD, get a second opinion to rule out any other possible psychiatric causes such as depression.

ADHD DRUGS: A Parent's Guide

Here are common pharmacological drugs used to reduce symptoms attributed to ADHD and their side effects:

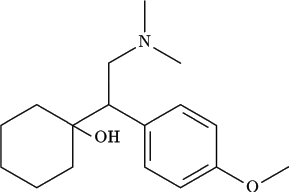

STIMULANTS Common brands: Ritalin, Concerta, Adderall, Cylert How they work: Increase brain activity, resulting in alertness and attention. What to know: Side effects may include decreased appetite, insomnia, headaches and mood changes. Ritalin has been linked to depression; Cylert has been linked to liver failure; and in February Canada suspended sales of Adderall XR after reports of sudden unexplained deaths of 20 U.S. children and adults who were taking the medication.

NONSTIMULANT Common brand: Strattera How it works: Increases access to a brain chemical thought to regulate impulse control and attention. What to know: It's not an FDA-controlled substance. Takes longer to start working, compared with stimulants. Side effects may include upset stomach, decreased appetite, dizziness, fatigue, mood swings. Long-term risks are unclean

ANTIDEPRESSANTS Common brands: Wellbutrin, Effexor; tricyclic antidepressants: Pamelor, Tofranil How they work: Change levels of brain chemicals; depending on the drugs, regulate mood, relieve tension or anxiety. What to know: Antidepressants are often used for children who have both ADHD and depression. Side effects may include weight loss, dizziness. The FDA has asked manufacturers to include warning labels alerting healthcare providers to an increased risk of suicidal thinking in children and adolescents being treated with these agents.

Can ADHD Be Treated Holistically?

While many medical professionals offer prescription drugs as a first choice to address ADHD symptoms, other alternatives exist:

HERBAL REMEDIES These supplements are not approved by the government, but some parents, like Dan Johnson, swear by them. He is a firm believer in Focus Attention, which contains the herbs ginkgo biloba and DMAE (dimethylaminoethanol, a compound in fish). Johnson's son, Christian, still has regular sessions with his psychiatrist, Karen TayIor-Crawford, M.D., director of the Disruptive Behavior Disorder Clinic at the University of Illinois Department of Psychiatry, focusing on behavior therapy. (Be sure to get a doctor's approval before giving children supplements.)

IMPROVED DIET Beverly Nicholson, Ph.D., an herbalist who runs the Herbal Connection Holistic Health Spa in Chicago, suggests that parents eliminate sugar and dairy from diets, consistently use multivitamins and herbal supplements, and think of medication as a last resort. The natural approach takes dedication and commitment, she warns: "Parents need to reassess their own lifestyle. You can't change your child's habits without changing your own."

Where to Go for Help

The following resources can help you understand your child's needs:

BOOKS

Delivered from Distraction: Getting the Most out of Life With Attention Deficit Disorder (Ballantine) by Edward M. Hallowell, M.D., and John J. Ratey, M.D.

Straight Talk About Psychiatric Medications for Kids (Guilford Press) by Timothy E. Wilens, M.D.

WEB SITES

Chadd.org--Children and Adults With AttentionDeficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD), which has chapters nationwide, offers resources, support and advocacy; (301) 306-7070.

Ldanatl.org--Learning Disabilities Association of America (LDA) is an international organization for children and adults with learning disabilities; (412) 341-1515.

Allkindsofminds.com--AII Kinds of Minds offers information and resources on learning differences; cofounded by Mel Levine, M.D., a leading expert in development and learning.

Nimh.nih.gov--National Institutes of Mental Health is the federal research agency for mental and behavioral disorders. NIMH's Web site has an extensive ADHD section.

REFERRALS

Association of Black Psychologists lists psychologists by state; (202) 722-0808; abpsi.org.

American Psychiatric Association, a national organization of psychiatrists, has a listing of district branches and state associations; (703) 907-7300; psych.org.

Robin D. Stone is a frequent contributor to ESSENCE.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Essence Communications, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group