Dr. Cal Cohen is the research director of the Community Research Initiative of New England, teaches at Harvard Medical School in Boston, and is affiliated with Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates. Dr. Cohen spoke with AIDS Treatment News on September 10, 2004.

Background: On August 2, 2004, the FDA approved two fixed-dose combinations of previously approved drugs; both are dosed for once-daily use by adults. The FDA said that these combinations should be used together with at least one other antiretroviral not in the nucleoside/nucleotide class. In practice, they have been tested and used mostly with Sustiva (efavirenz), and with at least one (boosted) protease inhibitor as well.

The two new combinations are:

* Epzicom--Ziagen (abacavir) + Epivir (3TC, lamivudine), and

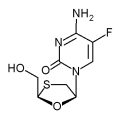

* Truvada--Viread (tenofovir) + Emtriva (FTC)

The studies cited below did not use the new combined pills, because they were not ready yet. They used the two separate drugs in the same doses.

AIDS Treatment News: Recently the FDA approved two once-a-day fixed-dose combination pills--Epzicom (Ziagen plus Epivir) from GlaxoSmithKline, and Truvada (Viread plus Emtriva) from Gilead Sciences. How do you see their use for patients who are first starting antiretrovirals?

Cal Cohen, M.D.: The fixed-dose combinations are primarily for convenience. The individual drugs were already approved in the U.S., and there is no medical reason that they had to be put into one pill. So the first decision is whether these are the right medicines for the patient.

The importance of fixed-dose combinations, and the reason there are now two more of them, is that several years ago, when AZT and 3TC were separate pills, Glaxo asked clinicians what they thought about putting them into one pill. As I recall, most of the doctors said that was not a priority, that their patients did not mind taking the extra pill. When Glaxo made Combivir anyway, its use was far greater than most physicians had predicted. Something about the simplicity was not anticipated, but was very important to many people taking these medicines. Maybe it was the one less co-pay, or one less bottle and refill to deal with. In any case the success of Combivir led to Trizivir (abacavir plus AZT plus 3TC), and now to these once-a-day combinations.

The issue of practicality and convenience is not to be minimized. But deciding which regimen you use is a choice of which meds you would pick, not just which fixed-dose combinations you would pick.

ATN: How do the once-a-day options compare with the twice-a-day antiretroviral treatments already in use?

Dr. Cohen: A head-to-head comparisons of Combivir vs. the same drug combination as Epzicom, presented in the fall of 2003 at the ICAAC conference, showed that the success of these regimens was spot-on identical. Sustiva was the 3rd drug in both cases.

The only differences were in side effects. With Epzicom, five to seven or eight percent of patients will have the hypersensitivity reaction to abacavir; this won't happen on Combivir. But there were other toxicities in favor of the Epzicom arm. For example, the CD4 counts went up higher on that arm than on the AZT-containing arm. There were fewer cases of nausea and vomiting, a well-known side effect of AZT. There was less anemia on Epzicom. Surprisingly there was a tiny bit more lipid increase on Epzicom than there was on Combivir. The significance of this difference is a subject of continued debate, but is just another factor to consider at this time.

So there is a series of tradeoffs--hypersensitivity in some cases with Epzicom, vs. better CD4 counts and less hematologic toxicity than with Combivir.

ATN: What about Truvada?

Dr. Cohen: In as statement on August 26, 2004, Gilead released early (24 week) results of a study comparing the Truvada drugs with Combivir (the other drug was Sustiva in both cases). That study showed a difference in the overall intent-to-treat response rate, giving an 8% advantage to Truvada over Combivir. ["Intent to treat" analysis compares the total percent of volunteers who meet the study-defined success criterion alter being assigned to take one drug vs. the other--regardless of whether the others had drug failure due to viral rebound, had to stop that treatment due to side effects, or simply were lost to followup so that data was unavailable.]

The 24-week result was about 88% (on Truvada) vs. 80% (on Combivir) of the volunteers having a viral load of fewer than 400 copies. It seems that some if not most of this difference is explained by toxicity, as the researchers found more toxicity on the Combivir arm than on the Truvada arm. Drug discontinuation due to toxicity seems to be explaining most of the difference in the intent-to-treat analysis, but further details are needed to truly answer the question, and those presentations are anticipated at ICAAC this year [October 30 through November 2, 2004].

Truvada is better than Combivir in some ways, and you have other advantages with Epzicom. The head-to-head test of Truvada vs. Epzicom has not yet been done: it is being planned through the government-funded ACTG trials network.

So how do physicians choose between these two? Epzicom has five to eight percent chance of hypersensitivity, which while manageable certainly, is an issue to be dealt with in those starting the treatment. Clinicians need to review the symptoms of hypersensitivity with anyone starting abacavir in this or any combination--as it is not yet standard to try to predict who is in this five to eight percent. This extra step will be a consideration in deciding when to use this treatment, for some clinicians at least.

Truvada has none of the hypersensitivity; it is a relatively easy drug. It is certainly well tolerated; very low rates of discontinuation have been seen fairly consistently with Truvada regimen, as well as in all the studies of tenofovir and FTC separately. Those are both well-tolerated drugs, with very low rates of discontinuation for side effects or lab toxicity. And overall the virologic success rates have been excellent.

The few concerns about Truvada have been mainly issues around renal (kidney) toxicity and dosing. These drugs are cleared by the kidney, and for those with compromised kidney function, the doctor has to pay attention to accurate dosing, to not overdose the patient. And some people are asking, if these drugs are cleared by the kidney, does that mean we will see more renal toxicity?

Several physicians have presented studies of large cohorts of patients in their clinics, and so far one can safely conclude that while there are case reports of people who have had laboratory changes and decreases in renal function on tenofovir-based regimens, some very large cohorts have reassured us that these changes are rare events, and we don't know how often they happen because of tenofovir, or at a rate different from other antiretrovirals. For example, in the head-to-head comparison of d4T vs. tenofovir, there was a very low rate of grade III renal problem on the d4T arm--and yet people don't worry' about d4T and renal toxicity. Just because there are case reports does not mean the tenofovir was involved. Most cohorts have been reassuring overall.

ATN: A statement on the labeling of tenofovir (at http://www.viread.com; see "Full prescribing Information," page 15 of the June 2004 version) noted slightly increased bone loss--and suggested that supplementation with calcium and vitamin D might help with that.

Dr. Cohen: There has been much discussion for at least five years on tenofovir and bone loss. In both arms of the study, d4T and tenofovir, there was evidence of bone loss in the first year. It was about 1% more on tenofovir than d4t, but it happened in both arms. We don't usually think of d4T, 3TC, and Sustiva having a problem of bone loss. It was almost identical for men on tenofovir and men on d4T--about 1% bone loss that stabilized after about one year. Only for women was the bone loss statistically worse for tenofovir.

So is this a tenofovir issue or an antiviral issue? The curves flatten out after a year--bone loss for the first year, and then there seems to be stabilization for about two years [beyond that we don't have much data]. If this were a drug toxicity, we would generally expect it to get worse over time, not get worse for a year and then stabilize.

Could HIV be contributing to the bone loss? Some data suggests that people with HIV have bone loss even without taking antiretrovirals. If we look at what happened in the year before they started antiretrovirals, there is data to suggest bone loss from untreated HIV. So one possible explanation for what we are seeing is that the HIV-related bone loss may be continuing for the first year on treatment; not till year two is the control of HIV resulting in a slowing of bone loss. This does not explain the 1% difference in women on tenofovir vs. d4T. There may be some contribution of drug toxicity and another effect of drug benefit, in terms of long-term stability of people.

2Whether that initial difference between tenofovir and d4t would be reversed by calcium supplementation is completely unanswered, at least from any public data sets. I am not aware that the bone loss is caused by the drug blocking calcium absorption in the gut. It would be an interesting study to see if calcium mattered or not. But for now it may be too simple to say bone loss happens and therefore calcium is the answer.

ATN: What about drug resistance with the new combinations?

Dr. Cohen: You don't have resistance too often with either of these starting regimens. But if you do, the choice is between tenofovir resistance and abacavir resistance (the percent of people who develop 3TC/FTC resistance is likely to be the same, based on these studies). There is no right or wrong answer; you don't want resistance to either one. Ultimately it is a tradeoff or other issues, since resistance to either abacavir or tenofovir causes cross-resistance to other medications in this class--and neither is a clear "'winner" on this aspect.

If you look at the mutations, about 2 to 3 percent of patients who start treatment with tenofovir regimens will get the K65R mutation, and about the same percentage who start with abacavir regimens will get the L74V mutation. Both these mutations can cause cross-resistance to other nucleoside analogs.

One key issue that may be important in how often we see these mutations is how often people with very low CD4 counts were allowed in these studies. A fact some people are not aware of is that the Gilead trial did not have a lower CD4 cutoff--you could have zero and still be eligible. The abacavir trials had a lower cutoff of 50. It turns out this matters in terms of resistance. Most of those who developed mutations in the Gilead study had low CD4s when they entered. In fact, the single best predictor of who would develop tenofovir resistance was the CD4 at entry. The median CD4 count of those who developed the K65R tenofovir mutation was around 25 cells.

Therefore you cannot directly compare these studies, because they did not enroll people at the same risk of resistance. If you look just at those entering with CD4 above 50, there were very few in the tenofovir study who developed resistance.

Whether the correlation with CD4 at entry is medical or behavioral is hard to say. It could be behavioral--if people who show up with that low a CD4 count are worse pill takers. Showing up with a CD4 count of 25 suggests that you are not actively pursuing health care in a preventive way. But it could also mean that the regimens may not be as protective at low CD4s as they are with less advanced disease, for biological reasons. We don't know the answer. We can observe that drugs work less well at very low CD4 counts, but don't know what explains this.

With these caveats, we now have a lot of confidence in Sustiva and two nucleosides. We have some differences in these regimens, and many similarities, Physicians are now gearing up to pick the one they think is best, given that treatment of HIV, at least in the U.S. and Europe, can be two pills once a day, with either fixed-dose combination you prefer. Overall I think that is wonderful.

The shorthand summary on which regimen (if one chooses one of these two once-a-day options) is that for some clinicians, it is a choice between the abacavir hypersensitivity story up front or not; they see this as a conversation that may leave patients feeling concerned about starting a medication that has that issue, rather than starting one that does not. That doesn't mean they won't use it. Sustiva's side effects, including vivid dreams and mood changes in many patients, have to be explained in either case. We are used to explaining the side effects of pills, but Truvada may have an easier starting conversation than Epzicom.

References

(1.) De Jesus E, Herrera G, Teolfilo E, and others, Abacavir versus zidovudine combined with lamivudine and efavirenz, for the treatment of antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected adults. Clinical Infectious Diseases. October 2004; volume 39, number 7, pages 1038-1046. Note: Originally reported at ICAAC: Efficacy and safety of abacavir (ABC) versus zidovudine (ZDV) in antiretroviral therapy naive adults with HIV-1 infection (study CNA30024). Program and abstracts of the 43rd Annual ICAAC Meeting, September 14-17, 2003, Chicago [Abstract H-446].

(2.) Gilead press release, August 26, 2004: Gilead announces preliminary 24-week data from study 934 comparing Viread and Emtriva to Combivir both in combination with efavirenz in patients with HIV. http://www.gilead.com/wt/sec/pr 607254.

COPYRIGHT 2004 John S. James

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group