CARDIOVASCULAR SERIES

Initiate treatment immediately to protect your patient from further injury.

MAXINE HILL, 59, arrives in the emergency department by ambulance. Diagnosed with hypertension 10 years ago, she'd been taking atenolol (Tenormin), a beta-blocker, to control her blood pressure (BP). But 6 months ago, she stopped taking it, telling her family she felt fine and didn't think she needed it. Her family called 911 today when she became short of breath and weak.

Mrs. Hill is receiving oxygen at 4 liters/minute by nasal cannula and D^sub 5^W intravenously (I.V). Alert and oriented, she tells you she can't breathe. The cardiac monitor shows sinus tachycardia with a heart rate of 130. Her BP is 224/130. You apply an automatic BP cuff and set it to check BP every 5 minutes. Listening to her chest, you hear an S^sub 3^ heart sound and bibasilar crackles in her lungs. You don't note any neurologic deficits.

Crisis vs. urgency

Although Mrs. Hill's BP is dangerously high, the physician must quickly determine whether it represents hypertensive crisis or hypertensive urgency before prescribing treatment. Hypertensive crisis means the patient's diastolic BP is above 120 mm Hg and she has end-organ damage, such as renal or heart failure (HF), myocardial ischemia or infarction, neurologic deficits, peripheral vascular disease, or retinal disease. (See Pinpointing a Crisis.) Hypertensive crisis requires immediate treatment to prevent further organ damage.

Hypertensive urgency occurs when the diastolic BP is above 120 mm Hg but other systems aren't damaged. It can be resolved more slowly than hypertensive crisis (within a few hours). In either case, lowering the patient's BP too quickly could precipitate end-organ ischemia or infarction.

Mrs. Hill has a 12-lead electrocardiogram that shows sinus tachycardia with nonspecific ST-T changes. A chest X-ray shows a slightly enlarged heart and fluid in both lung bases, and an echocardiogram shows decreased left ventricular function. The physician diagnoses hypertensive crisis with HF.

The precipitating factor probably was an abrupt increase in systemic vascular resistance caused by chronic hypertension. Over time, hypertension has damaged the endothelium in Mrs. Hill's arterioles; her body's protective responses have become ineffective, and her myocardium has been damaged. (To learn more about endothelial dysfunction, see "Improving the Odds against Hypertension" in the August issue of Nursing2001.)

Proceed with caution

The immediate goal in treating hypertensive crisis is to reduce the patient's mean arterial pressure by 25% within minutes to 2 hours, then to reduce diastolic BP to less than 100 mm Hg within 2 to 6 hours. The only exception would be a patient with acute aortic dissection, whose BP should be reduced within 10 minutes to prevent rupture.

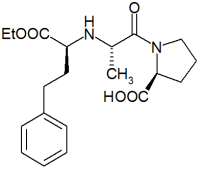

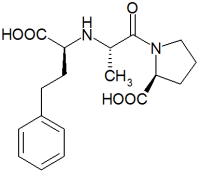

Initially, Mrs. Hill will receive I.V. medications. (See Choosing an Appropriate Drug.) The physician orders a continuous I.V. infusion of nitroprusside, and I.V. enalaprilat, an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor, every 6 hours. To help her through the crisis, take these steps.

Measure her BP in both arms while she's supine and standing, if possible. Take readings at least every 5 minutes at first, then at longer intervals as her condition starts to stabilize. Correlate intra-arterial or automatic BP readings with manual cuff readings at least hourly.

* Give I.V. drugs as ordered. If her condition worsens, slow or stop treatment, especially if she exhibits signs and symptoms of a stroke.

* Administer oxygen therapy to maintain Spo^sub 2^ at 92% or greater.

* Maintain cardiac monitoring to detect and treat arrhythmias.

* Once her diastolic BP drops below 100 mm Hg, administer oral medications as ordered.

After the fall

Within 2 hours, Mrs. Hill's BP is 180/90. She's transferred to the critical care unit and receives nitroprusside for 36 hours. She begins therapy with oral enalapril and a longacting nitrate to treat her HF.

When she's transferred to a medical/surgical unit, a dietitian helps her work out a food plan and a nurse from cardiac rehabilitation develops a low-level exercise program. Her primary nurse teaches her about the names and dosages of medications she'll take at home: how and when to take them and potential adverse reactions or drug-- food interactions. He emphasizes the importance of taking them as ordered and not stopping just because she feels well. Scheduled for an outpatient echocardiogram to assess myocardial function, she's discharged 4 days after admission.

Emergency resolved

By recognizing Mrs. Hill's hypertensive crisis and responding appropriately, you've helped her prevent further end-organ damage and prepared her to ward off future hypertensive emergencies.

SELECTED REFERENCES

Bales, A.: "Hypertensive Crisis: How to Tell if It's an Emergency or an Urgency," Postgraduate Medicine. 105(5):119-130, May 1999.

Barish, R., and Naradzay, J.: "Approach to Cardiovascular Emergencies," in Primary Cardiology, L. Goldman and E. Braunwald, eds. Philadelphia, Pa., W.B. Saunders Co., 1998.

Chase, S.: "Hypertensive Crisis," RN. 63(6):62-- 67, June 2000.

Varon, J., and Marik, P.: "The Diagnosis and Management of Hypertensive Crisis," Chest. 118(1):214-227, July 2000.

BY VICKIE A. MIRACLE, RN, CCNS, CCRN, EDD

Director of Education

Jewish Hospital, Heart and Lung Institute * Louisville, Ky.

Copyright Springhouse Corporation Sep 2001

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved