This article is a practical, precise and concise overview of my 7.5 years of experience treating a broad range of sleep problems in a heterogeneous group of HIV-infected individuals at the Thomas Street Clinic (TSC) in Houston. TSC is a community-based clinic that provides primary medical care to the indigent HIV/AIDS community.

Introduction. Like HIV infection itself, insomnia is a significant public health problem. The economic, human and societal costs of insomnia affect health care utilization, quality of life, relationships and productivity. Rosekind (1992) estimates that while 95% of the US population experiences occasional insomnia, only one third to one half of these people seek medical help and seldom report insomnia as their primary complaint. Furthermore, an average of 14 years elapse before they come in for treatment. These odds get stacked even higher when HIV and related issues are added to the mix, as demonstrated by Rubinstein and Selwyn (1998). They classified 73% of 115 patients as having a sleep disturbance. Insomnia rose to 86% in drug users and to a whopping 100% in those with cognitive impairment. Similar to the underreporting of patient sleep problems, clinicians identified insomnia in only 33% of medical records. Prenzlauer et al. (1993) correlated sleep with the stage and markers of HIV illness and with psychosocial factors in 68 patients. Fifty patients (79%) had a sleep disturbance. The trend towards higher beta 2 microglobulin levels in this group may well be an early indicator of disease progression.

Sleep is not just the absence of wakefulness. It is also a state of rest for voluntary functions while vitally important involuntary functions persist. The dormancy may be essential to reduce the energy requirements of the brain and to allow adequate rest for the forebrain. Long- and short-term sleep deprivation results in impaired thinking, speaking, memory, concentration and judgement. Irritability increases and reaction time slows down. Paranoia and visual, tactile and auditory hallucinations are often a result of long-term sleep deprivation. It is easy to extrapolate the impact of these symptoms on objective productivity, subjective quality of life and mutual relationships. The Gallup Survey estimates that sleep problems cost the health care system alone $30 billion annually.

Diagnosis. Given the fact that sleep problems are underreported, underdiagnosed, costly and proven to have a negative impact on our patients' lives, it is important for us all to have a working knowledge of commonly encountered sleep disorders in HIV/AIDS. The symptoms of insomnia may result from a variety of medical, psychiatric or neurologic conditions. A thorough sleep history is usually sufficient to diagnose the bulk of etiologies. Occasionally though I have had to send patients to the sleep lab not only for diagnosis but also for intervention like the continuous positive airway pressure (C-PAP) machine.

The sleep history must include the following considerations:

* Whether insomnia is initial, middle or terminal (i.e. does the patient have problems going to sleep, staying asleep or waking up earlier than they want to?)

* Specific retiring and arising time, any recent changes in this schedule, and variation between weekdays and weekends.

* Subjective quality and ideal personal quantity of sleep. How often are there problems sleeping?

* Daytime sleepiness and naps during the day, as well as the timing of naps.

* Drug and alcohol use. It is important to consider withdrawal symptoms from alcohol and sedating drugs in the etiology of insomnia. Ask about caffeine use. Do not forget to include cola drink consumption habits.

* Sleep hygiene: eating habits, comfort of bedroom or sleep environment, temperature, noise, and stress.

* Medical problems (including pain and psychiatric problems) and how these have been treated.

* A complete physical exam. This can be a useful guide to well-directed laboratory studies that may yield valuable information about endocrine, cardiovascular, neurologic and respiratory causes of insomnia. However, an exhaustive discussion of these causes is beyond the scope of this paper.

Nonpharmacological management. An old Indian proverb suggests, "One kind of stick cannot be used to corral all sheep." While it loses something in the translation, this proverb is quite apropos to the current discussion in the sense that a single approach cannot fix all patients' problems. Nonpharmacological options remain the mainstay of dealing with psychological factors that hinder sleep. They include the following approaches:

A) Behavioral

* Sleep hygiene: stresses habits, and environmental and physiological factors that promote sound sleep.

* Stimulus control: limits sleep-incompatible behaviors that may become associated with bed.

* Sleep restriction: limits time in bed and causes mild sleep deprivation, which leads to increased sleep efficiency.

* Relaxation training: utilizes biofeedback, progressive muscle relaxation, autogenic training and guided imagery to achieve a state of relaxation incompatible with insomnia.

B) Psychological

* Paradoxical intention: instructs patient to concentrate on staying awake in order to reduce fruitless efforts to fall asleep.

* Cognitive therapy: explores faulty assumptions and beliefs about insomnia and provides more rational alternatives.

* Psychotherapy

To summarize in practical terms, the do's and don'ts that should discussed with patients include the following points.

Do

- sleep only enough to be refreshed

- wake up at the same time everyday

- exercise daily

- avoid noise and extremes of temperature

Don't

- go to bed hungry

- take a sleeping pill every day

- drink caffeinated beverages or alcohol before bedtime

- smoke before bedtime

- try harder to sleep if you cannot sleep in a reasonable amount of time

- nap during the daytime

Pharmacological management. Frequently used classes of medications at TSC include benzodiazepines, sedating antidepressants, imidazopyridines and over the counter drugs. Many of the drugs mentioned below are available as either generics or brand-name drugs. Principles of treatment of insomnia are illustrated by the following case examples that are composites of HIV-infected patients commonly seen at TSC.

* Andrew is a 32-year-old man who has no current or past psychiatric symptoms. He denies substance abuse and comes in complaining of difficulty falling asleep. Once he falls asleep, he is able to remain asleep until he wakes up in the morning. He wakes up feeling tired because he is unable to get more than 3 hours of sleep before he finally gets up to carry out his usual routine. Andrew would be an ideal candidate for the short-term use of zolpidem (Ambien), a short-acting imidazopyridine, which has a short latency of action and no hangover side effects. He would also benefit from sleep restriction (i.e. being advised to get out of bed if he cannot sleep after more than 30 minutes in bed). He is also asked to move the TV from his bedroom so that the bedroom now becomes a place of rest and repose.

* Belle, a recovering alcoholic currently staying in a residential treatment setting, complains of restless and unrefreshing sleep. She denies any other neurovegetative symptoms of depression or anxiety but worries about being able to maintain her sobriety if the insomnia continues. Belle would benefit from the use of a sedating antidepressant like trazodone (Desyrel). This is not contraindicated in a recovering alcoholic, can be titrated upwards to tolerance and poses no risk of priapism (nonexistent in a woman). During the course of her psychotherapy, Belle is constantly reassured that her particular type of insomnia will resolve with the passage of time, as she continues to abstain from alcohol.

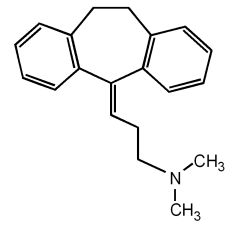

* Cassidy is a diabetic patient treated at different times with zidovudine (Retrovir) and stavudine (Zerit). He complains of being unable to sleep because of tingling and numbness in his extremities. Cassidy was prescribed a sedating antidepressant, amitriptyline (Elavil or Endep), which has significant analgesic effects that helped manage the peripheral neuropathy resulting from diabetes and antiretrovirals.

* Dexter has been having problems sleeping ever since he was prescribed lamivudine (Epivir). He reports problems with both initiating and maintaining sleep. There is a remote history of cocaine abuse, but Dexter has turned his life over to God and sobered up ever since being diagnosed with AIDS a few years ago. It was decided that it would be safe to prescribe Dexter a long-acting benzodiazepine. He was prescribed clonazepam (Klonopin). Continued participation in 12-step groups was strongly recommended. The risk of abuse and dependence of clonazepam was discussed, particularly with its potential long-term use being a distinct possibility given the etiology of insomnia. Drug holidays were also recommended to decrease the onset of tolerance to drug effects.

* Eduardo presented with sleep interrupted by painful diarrhea. He woefully described how he had to get up more than 6 times every night to use the restroom and often was unable to make it to the restroom in time. Workup for the symptoms was in progress but his quality of life was tremendously compromised in the meantime. On discussion with his infectious disease physician, there was no contraindication to treating the diarrhea. A long-acting opioid was prescribed for Eduardo to treat the pain and also to bind the diarrhea. A consultation was obtained with a registered dietician to see if dietary modifications would be advised.

* Fenella came in complaining of difficulty sleeping through the night. She feels tired during the day but is unable to rest, being agitated and on-edge. She has experienced a complete lack of interest in her usual activities and has lost 10 lbs in the past month because "food does not taste as good." She decided to come in because she feels that one night of adequate rest would help her overcome all the setbacks she so freely described. It is difficult to convince Fenella that her sleep problem is related to her depression. However, she agrees to take an antidepressant only if it will help her sleep. When assured that mirtazepine (Remeron), a sedating antidepressant, will help her sleep as well as treat her depression, she agrees to give it a chance. She is referred for cognitive therapy as an adjunctive measure for the treatment of her sleep disorder as well as her depression.

* Gustavo is on a combination of indinavir (Crixivan), lamivudine and stavudine. Already a husky man, he has gained additional weight on this regimen and now tips the scales at close to 300 lbs. He was referred because of his poor quality of nighttime sleep, which fails to respond to temazepam (Restoril) at a 60 mg dose. Gustavo is able to pinpoint the gradual onset of poor sleep to when he had started putting on the excess weight. He also admits to loud snoring, which sometimes wakes him up in near panic. A tentative diagnosis of sleep apnea is made, the temazepam is discontinued and a weight loss regimen is established. Gustavo is also sent to the sleep laboratory to be fitted with a C-PAP device if necessary.

I present these case examples as stereotypes of patients I treat. Rarely are the histories so clear-cut. I have deliberately omitted specifics about dosing strategies and follow-up care in the interest of brevity and clarity. General guidelines I would like to stress for the pharmacological treatment of insomnia, in particular with controlled substances, can be summarized as follows:

Do prescribe

- for transient insomnia due to alterations in sleep conditions

- for short-term insomnia related to stress for 1 or 2 weeks

- intermittently for chronic insomnia

Don't prescribe

- without an accurate diagnosis

- for long periods of time, except in certain circumstances such as when the precipitating cause of insomnia is not likely to resolve (e.g. medication-induced insomnia, intractable pain, etc.)

- without appropriate dose adjustments and periodic review to ensure that changing HAART regimens has not led to newer contraindications

- for patients who continue to abuse alcohol or drugs

Conclusion. Insomnia is common in HIV/AIDS. It is underdiagnosed and undertreated. To be treated, insomnia must be diagnosed. A combination of behavioral and psychological approaches are highly effective in managing complaints of insomnia. Treating insomnia can be rewarding for patients and physicians alike.

GLOSSARY

Analgesic: producing an insensibility to pain, without a loss of consciousness.

Autogenic: relating to relaxation techniques (such as biofeedback or meditation) in an attempt to control physiological characteristics (blood pressure, heart rate, etc.).

Neurovegetative: occurring involuntarily (autonomic).

Priapism: an abnormal, persistent and usually painful erection of the penis (not caused by sexual desire).

REFERENCES

Ashton H. The effect of drugs on sleep. In Cooper, ed. Sleep. London: Chapman & Hall Medical, 1994: 175-211.

Becker B. Relief from sleep disorders. New York: Dell Medical Library, 1993.

Bootzin RR, Perlis ML. Nonpharmacologic management of insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry 1992; 53 (suppl 6): 37-41.

The Gallup Survey. Sleep in America. A National Survey of US Adults: Final Report. Princeton, NJ: The Gallup Organization, 1995.

Prenzlauer SL, Bogdanov L, Tiamson ML, Bialer PA Wilets I. Sleep and HIV illness. Int Conf AIDS 1993 Jun 6-11;9(1);427.

Gokcebay N, Cooper R, Williams RI, Hirshkowitz M, Moore CA. Function of sleep. In Cooper, ed. Sleep. London: Chapman and Hall Medical, 1994: 47-59.

Rosekind MR. The epidemiology and occurrence of insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry. 1992;(suppl 6):4-6.

Rubinstein ML, Selwyn PA. High prevalence of insomnia in an outpatient population with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defici Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1998. Nov 1;19(3):260-265.

Zishan Samiuddin, MD Baylor College of Medicine

COPYRIGHT 2000 The Center for AIDS: Hope & Remembrance Project

COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group