Depression, a multifaceted sense of abnormal sadness or grief, is the oldest and most frequently discussed psychiatric illness.(1) The word depression is used to describe a symptom or syndrome, an emotional state, a reaction, a disease, a sign, or a clinical entity. Depression can range from mild to severe, and it can be associated with psychotic behavior and suicidal ideation.(2) An older term for depression is melancholia.

In addition to the obvious emotional consequences, depression affects individuals' ability to function, increases use of health care resources, leads to lost work days, and decreases productivity.(3) Signs and symptoms of depression include

* inability to concentrate;

* decreased energy;

* anxiety;

* prolonged depressed mood most of every day;

* significant weight loss or gain;

* lack of interest in activities or usually pleasurable events;

* agitation;

* crying;

* suicidal thoughts; waking early in the morning, insomnia, or

hyper-somnia nearly every day; and

* feelings of excessive or inappropriate guilt or

worthlessness.

An individual must experience some of these symptoms for at least two weeks to have a diagnosis of depression.(4)

More than eight million Americans suffer episodes of major depression sometime during their lives, but only 25% of affected individuals seek medical attention for this disorder.(5) The peak age for depression is between 40 and 50 years of age, and twice as many women as men are affected.(6) Suicide is a significant risk for individuals with depression.

TREATMENT METHODS

Depression is a serious, potentially life-threatening condition that warrants initiation of treatment as soon as the diagnosis is confirmed. Treatment may include the use of antidepressant medications and/or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in conjunction with psychotherapy. Although this article focuses on ECT, antidepressant medications and psychotherapy also will be discussed. Psychotherapy alone may not be the most appropriate primary treatment plan for every individual with depression; however, frequent psychotherapy sessions may help health care professionals assess individuals' progress. Combinations of psychotherapy and antidepressant medications may provide therapists with greater understandings of the efficacy of prescribed medications.(7)

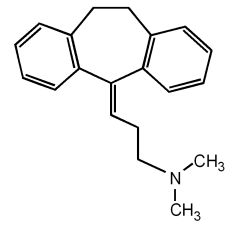

Antidepressant medications. Current theories about the causes of depression (eg, serotonergic tryptamine, noradrenergic, cholinergic, dopaminergic, y-aminobutyricergic) focus on malfunctioning chemical neurotransmitter mechanisms.(8) Antidepressant medications (Table 1) elevate depressed individuals' moods by manipulating their neurotransmitter systems.

Electroconvulsive therapy. Although 65% to 90% of depressed individuals respond favorably to antidepressant medication therapy,(17) the remaining 10% to 35% are unable to tolerate the medications' side effects or are unresponsive to these medications. For these individuals, ECT offers an alternative treatment. More than 70% of depressed individuals achieve positive outcomes from ECT,(18) which is encouraging for elderly and pregnant patients, who are unable to take many psychotropic medications, and for women, who represent a large percentage of individuals with depression.(19)

Electroconvulsive therapy was used clinically for the first time in 1938.(20) Since that time, ECT has been used to treat affective disorders (eg, depression, bipolar disorders), schizophrenia, mania, and catatonia and to reduce symptoms of tardive dyskinesia and Parkinson's disease.(21) Until antidepressant medications were introduced in the late 1950s, ECT was a common treatment modality. From 1960 to the early 1990s, ECT was used rarely because medications were the mainstay of treatment for depression. In the past few years, psychiatrists have begun using ECT more often because of increased concerns about the side effects, safety, and efficacy of psychotropic medications. The therapeutic effect of ECT is attributed to its causing an alteration in the post-synaptic response to central nervous system neurotransmitters. Electroconvulsive therapy is thought to stimulate synaptic remodeling, which increases synaptic proteins, enhancing positive behavior and relieving symptoms of depression.(22)

Electroconvulsive therapy is somewhat controversial, primarily due to the side effects (eg, brief headaches, short-term memory loss) associated with this treatment modality.(23) Proponents of ECT believe the side effects are minimal and that the potential for fractures, dislocations, and severe muscle spasms is reduced greatly by administering muscle relaxants, anesthetic agents, and oxygen during ECT. Opponents of ECT believe that it causes brain damage (eg, permanent memory loss, aphasia), severe confusion, cognitive impairment (eg, directional problems, reduced ability to learn new material), and frequent disabling fractures.(24) Media depictions of ECT's being used punitively have contributed to this controversy. Despite ECT's safety record and the abundance of supporting data, skeptics still oppose its use.(25) An article published in 1991 revealed that 40% of psychiatrists in a survey believed that ECT was either totally unacceptable, a last-resort measure, or a treatment that should be curtailed.(26) Several authors have suggested changing the name of this treatment modality to "cerebroversion" or "brain stimulation therapy" to help create a more positive image for ECT.(27)

OUIPATIENT ELECTROCONVULSIVE THERAPY

Some individuals with depression benefit from maintenance ECT, which is performed prophylactically to prevent relapses after they have completed inpatient ECT. The frequency of maintenance ECT is individualized according to psychiatrists' treatment plans and individuals' symptoms and may be scheduled weekly, every two weeks, or monthly.(28)

Maintenance ECT can be performed successfully through ambulatory surgery units (ASUs) and postanesthesia care units (PACUs). Just as all patients who require surgery or major diagnostic medical procedures are not necessarily good candidates for ambulatory procedures, not all individuals with depression are candidates for outpatient ECT. For example, an individual who needs ECT may not meet a facility's distance criteria (ie, may reside too far from the facility) or may not meet the facility's patient anesthesia classification criteria. Most facilities also require that responsible adults drive individuals home after they undergo outpatient ECT procedures, and most facilities that offer outpatient ECT require approval by specific physicians (eg, anesthesia department chiefs, chief psychiatrists). For example, at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Memphis, only a staff attending psychiatrist can administer ECT.

Regardless of the setting in which ECT is performed, the same standards for patient assessment, level of care, available monitoring, and competent personnel must be maintained. Nurses in ASUs and PACUs who are familiar with ECT can help identify individuals for whom outpatient ECT is appropriate. Fulfilling this role will require nurses who work in these settings to learn more about basic biologic psychiatry. A study in 1995 reported that psychiatric nurses perceived that they had knowledge deficits relative to biologic psychiatry.(29) If these specialist nurses were unfamiliar with basic biologic psychiatry principles, ASU and PACU nurses may require even more continuing education to meet the needs of individuals who undergo outpatient maintenance ECT.

Preprocedural care. When a psychiatrist recommends ECT, he or she advises the individual and family members of the purpose, risks, and benefits of ECT and explains other treatment options. If this information is explained thoroughly, any indivudual--regardless of his or her psychiatric diagnosis- should be able to give informed consent.(30) The risks and potential side effects of ECT include

* anoxia during the apneic period after the seizure;

* memory loss; and a mortality rate of one death per 10,000 treatments,

related to anesthesia complications and ventricular

arrhythmias.(31)

Electroconvulsive therapy is contraindicated for individuals with severe cardiac conditions, severe hypertension, cerebral lesions, and musculoskeletal injuries or abnormalities (eg, spinal column injuries).(32)

The psychiatrist and nurse provide oral and written preprocedural instructions, which include the arrival date and time; directions to abstain from liquids and food after midnight the night before the procedure and to discontinue certain medications (eg, lithium, theophylline, medications that may increase the seizure threshold); instructions to remove wigs, jewelry, hair pins, nail polish, dentures, glasses, and contact lenses; and the need for a responsible adult to drive the individual home after the procedure and to provide postprocedural care. Perioperative nurses reinforce this information by explaining the purpose of ECT and the treatment protocol to individuals and family members and by preparing them psychologically for ECT.

Individuals who undergo outpatient ECT require perioperative nursing care that is similar to the care provided patients scheduled for ambulatory surgery procedures. A perioperative nurse completes the admission form, which includes a patient assessment as well as verification of the results of preprocedural studies (eg, blood chemistries; urinalysis; chest x-ray; spinal x-rays; electrocardiogram [ECG]; electroencephalogram [EEG]; computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the patient's head to rule out space-occupying lesions that can cause edema, increased intracranial pressure, or bleeding).(33) He or she obtains a baseline set of vital signs (ie, pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate, temperature). The patient changes into a gown and empties his or her bladder. After checking that the patient has given informed consent, the nurse administers the preoperative anticholinergic medication (eg, intramuscular atropine 0.4 mg) to decrease oral secretions and the risk of aspiration during ECT and to prevent cardiac dysrhythmias.

Procedure. At the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Memphis, we administer ECT in the PACU because anesthesia care providers and nurses with critical care experience are available. Before bringing the patient to the PACU, nurses have assembled the required equipment, supplies, and medications (Figure 1), which include

* the ECT machine (Figure 2) and electrodes;

* an ECG monitor;

* a pulse oximetry monitor;

* an oxygen source and mask;

* an EEG monitor, leads, and application gel;

* a bite block; skin cleansing solution; and

* methohexital sodium (ie, Brevital) and succinylcholine chloride (ie, Anectine) or propofol (ie, Diprivan) and midazolam hydrochloride (ie, Versed).

[Figures 1 and 2 ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

The perioperative nurse or psychiatric clinical nurse specialist transports the patient to the PACU and offers reassurance and explanations of all activities and procedures. The nurse assists the anesthesia care provider in attaching ECG and pulse oximetry leads to the patient. The anesthesia care provider inserts a peripheral angiocatheter, after which the nurse cleans the patient's scalp and applies the EEG monitor electrodes.

Electrode placement. The psychiatrist places the ECT electrodes and determines the amount of electrical current (ie, stimulus intensity) that will be used. The higher the stimulus intensity, the longer the seizure that is produced. The ECT electrodes can be placed either unilaterally or bilaterally. Unilateral placement on the patient's nondominant side of the brain is used in less complicated conditions and often results in less postprocedural confusion.(34) Bilateral electrode placement is used for patients with Parkinson's disease, severe depression, agitation, suicide risk, psychosis, mania, catatonia, and schizophrenia that is nonresponsive to other treatment.(35) After the ECT electrodes are secured, the psychiatrist runs a monitor strip to verify electrode placement and ECT machine function.

Medication. The anesthesia care provider administers a combination of a fast, short-acting anesthetic (eg, IV methohexital sodium 0.75 mg/kg, propofol 2.0 mg/kg, midazolam hydrochloride 0.3 mg/kg) and a muscle relaxant (ie, IV succinylcholine chlorine 0.5 mg/kg)(36) When the patient is relaxed completely, the anesthesia care provider inserts an oral airway, places an oxygen mask over the patient's nose and mouth, and administers 100% oxygen at 10 L per minute.

Seizure induction. The psychiatrist administers the electrical stimulus that induces grand mal seizure activity. As the electrical stimulus is applied, the patient experiences a period of muscle contraction, followed by the tonic phase of a seizure and then the clonic phase. The central seizure occurs only in the brain, and the general anesthetic and muscle relaxants make the phases of the seizure barely discernible. The seizure initiates a cascade of biochemical and neuroendocrine events,(37) which should correct biochemical abnormalities in the patient's brain and produce an antidepressant effect. For an effective outcome, the patient must have a seizure that lasts at least 25 seconds. The psychiatrist, anesthesia care provider, and perioperative nurse verify the seizure duration by observing the EEG monitor.(38) After the seizure, the patient begins breathing spontaneously in one to two minutes and regains consciousness shortly afterward.

Postprocedural care. The ECT procedure is brief, and the patient generally requires two hours or less of nursing care in the PACU.(39) The nurses keep the patient's bed side rails in the upright position and observe the patient for any further seizure activity or respiratory or cardiac function compromise. They monitor the patient's vital signs every five minutes until the patient awakens and then every 15 minutes until the patient is alert. They maintain the patient in a side-lying position and suction the patient's airway as needed. If the patient has a pharyngeal airway, the nurses remove it when the patient begins breathing spontaneously. The PACU nurses remove the EEG electrodes and clean the patient's scalp and hair. If the patient has experienced incontinence during ECT, the PACU nurses clean the patient's skin and provide dry clothing. When the patient's vital signs are stable, the PACU nurses call report to the ASU nurse. They then transport the patient to the ASU, where the nurses continue to assess the patient and attend to his or her safety and comfort needs. Some patients are hyperactive or restless after ECT. If the patient is disoriented, a longer observation period in the ASU is indicated.

Each facility has specific discharge criteria for patients who have outpatient ECT. At our facility, a patient who has undergone outpatient ECT cannot be discharged until he or she has stable vital signs, is able to void and tolerate oral liquids, and has discharge orders written by the psychiatrist. A responsible adult must be available to drive the patient home and provide postprocedural care.

Discharge teaching. Just as postoperative teaching is essential for ambulatory surgery patients, postprocedural instruction is important for patients who have undergone outpatient ECT. Two notable differences exist, however, between patients who have undergone ambulatory surgery and those who have had outpatient ECT. Unlike a postoperative patient, a patient who has undergone outpatient ECT does not require prescriptions for analgesic medications. The second difference relates to activity and decision making. All surgical patients are instructed to avoid driving, operating machinery, consuming alcohol, or making major decisions during the first few days after surgery. Instructions about avoiding these activities are even more important for a patient who has undergone outpatient ECT because he or she may experience retrograde memory loss or confusion for up to two weeks after the procedure. The patient also may experience anterograde memory loss (ie, have trouble retaining newly learned material) during this time. Perioperative nurses must, therefore, explain these restrictions to the adult who accompanies the patient.(40)

CASE STUDY

Ms J was a 38-year-old female who had been diagnosed 16 years earlier as having major depression. She had been hospitalized numerous times in both public and private institutions in other parts of the country. Between hospitalizations, Ms J had been treated with medications and psychotherapy in outpatient psychiatric clinics and in supervised day treatment programs. Ms J also had received ECT during three previous hospitalizations and reported having decreased symptoms of depression for approximately eight months after each inpatient ECT series.

Ms J's pattern of frequent, lengthy hospitalizations followed by brief two- to three-month periods of outpatient treatment continued when she sought treatment at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Memphis. She engaged in individual psychotherapy, but the severity of her depression and the need for frequent hospitalizations hampered her progress in therapy. Ms J received inpatient ECT during her first hospitalization at this facility, but obtained only short-term relief from her depression. During a subsequent hospitalization, she underwent a second inpatient ECT series, after which plans were formulated to continue outpatient maintenance ECT on a monthly basis. The goal of the outpatient maintenance ECT was to diminish Ms J's level of depression and to prevent inpatient hospitalizations so she could continue to work on problem areas in her individual psychotherapy sessions.

In preparation for outpatient maintenance ECT, a psychiatrist and psychiatric clinical nurse specialist maintained ongoing contact with Ms J to complete appropriate preprocedural assessments, documents, and consent for each ECT session. Nurses in the ASU assumed responsibility for Ms J's preprocedural and postprocedural care, and PACU nurses were responsible for her care during ECT sessions. Nurses in the outpatient psychiatric clinic, ASU, and PACU communicated frequently about Ms J to coordinate her care. While receiving outpatient maintenance ECT, Ms J also continued taking antidepressant medications and engaging in weekly psychotherapy sessions. Although she experienced slight memory loss during the week after each ECT session, this memory loss was not significant and did not interfere with the overall treatment of her depression.

In the years before beginning outpatient maintenance ECT,Ms J had five hospitalizations totaling 147 inpatient days. The frequency and duration of inpatient admissions decreased during the year that she received outpatient maintenance ECT and supportive programs. Moreover, the ECT provided Ms J sufficient relief from depression to enable her to benefit more fully from antidepressant medications and psychotherapy.

CONCLUSION

Reducing hospitalizations has become the focus of many health care administrators in the current redesign of health care delivery. This trend has increased the number of outpatient surgical and invasive procedures substantially during the past decade.(41) The advances in technology, which have facilitated the performance of more ambulatory surgery procedures, have parallels in psychiatry, where new, sophisticated ECT machines are being used and more patients are receiving outpatient maintenance ECT.(42) Continued ECT research is paramount. Studies about electrode placement and threshold dosages are laying the groundwork for the greater use of ECT.(43) New techniques involve the use of magnetic stimulation, which may produce the effects of ECT without the seizures.(44)

Electroconvulsive therapy offers patients with major depression, bipolar disorders, or schizophrenia a safe outpatient treatment alternative. With increased outpatient services, decreased health care resources, and the strong influence of third-party payers, outpatient ECT has tremendous financial potential. Successful performance of outpatient ECT requires collaboration by skilled perioperative nurses, psychiatrists, anesthesia care providers, patients, and family members.

NOTES

(1.) R P Rawlins, "Hope-Despair," in Mental Health-Psychiatric Nursing: A Holistic Life-Cycle Approach, second ed, C K Beck, R P Rawlins, S R Williams, eds (St Louis: The C V Mosby Co, 1988) 264.

(2.) G W Stuart, S J Sundeen, Principles and Practice of Psychiatric Nursing, fourth ed (St Louis: Mosby-Year Book, Inc, 1991) 416.

(3.) L Citrome, "Management of depression: Current options for this highly treatable disorder," Postgraduate Medicine 95 (January 1994) 137-145.

(4.) D M Kradecki, M L Tarki-now, "Erasing the stigma of electroconvulsive therapy," Journal of Post Anesthesia Nursing 7 (April 1992) 84-88.

(5.) D Kupecz, "New antidepressants," Nurse Practitioner 20 (September 1995) 64-67.

(6.) Stuart, Sundeen, Principles and Practice of Psychiatric Nursing, fourth ed, 416.

(7.) R Post, "Mood disorders: Somatic treatment," in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, vol 1, sixth ed, H I Kaplan, B J Sadock, eds (Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1995) 1152-1178.

(8.) C M Taylor, Mereness' Essentials of Psychiatric Nursing, 13th ed (St Louis: The C V Mosby Co, 1990) 179-189.

(9.) Citrome, "Management of depression: Current opinions for this highly treatable disorder," 140.

(10.) L Fitzsimons, "Electroconvulsive therapy: What nurses need to know," Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 33 (December 1995) 14-17.

(11.) Citrome, "Management of depression: Current opinions for this highly treatable disorder," 140.

(12.) Ibid, 141.

(13.) L Skidmore-Roth, Mosby's 1994 Nursing Drug Reference (St Louis: Mosby-Year Book, Inc, 1994) 830.

(14.) Kupecz, "New antidepressants," 66.

(15.) Ibid, 64-66.

(16.) Post, "Mood disorders: Somatic treatment," 1162.

(17.) Kupecz, "New antidepressants," 64.

(18.) Fitzsimons, "Electroconvulsive therapy: What nurses need to know," 14.

(19.) Stuart, Sundeen, Principles and Practice of Psychiatric Nursing, fourth ed, 416.

(20.) Fitzsimons, "Electroconvulsive therapy: What nurses need to know," 14.

(21.) Kradecki, Tarkinow, "Erasing the stigma of electroconvulsive therapy," 85.

(22.) R M Fraser, ECT: A Clinical Guide (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1982).

(23.) Kradecki, Tarkinow, "Erasing the stigma of electroconvulsive therapy," 87.

(24.) Ibid, 88.

(25.) M Fink, "Impact of the antipsychiatry movement on the revival of electroconvulsive therapy in the United States," Psychiatric Clinics of North America 14 (December 1991) 793-801.

(26). S Dubovsky, "Electroconvulsive therapy," in Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry, vol 2, sixth ed, H I Kaplan, B J Sadock, eds (Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1995) 2129-2140.

(27.) D P Hay, L Hay,H Spiro, "The enigma of the stigma of ECT: 50 years of myth and misrepresentation," Wisconsin Medical Journal 88 (December 1989) 4-10; D Goleman, "The quiet comeback of electroshock therapy," New York Times Health, 12 Aug 1990, sec B7; D Hay, "Electroconvulsive therapy, mental health, and aging," International Journal of Technology and Aging 3 (Spring 1990) 39-45.

(28.) V G Stiebel, "Maintenance electroconvulsive therapy for chronic mentally ill patients: A case series," Psychiatric Services 46 (March 1995) 265-268.

(29.) L M Fitzsimons, R L Mayer, "Soaring beyond the cuckoo's nest: Health care reform and ECT," Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 33 (December 1995) 10-13.

(30.) Dubovsky,"Electroconvulsive therapy," 2132.

(31.) J Haber, "Management of depression and suicide," in Comprehensive Psychiatric Nursing, fourth ed, J Haber et al, eds (St Louis: Mosby-Year Book, Inc, 1992) 578.

(32.) Ibid.

(33.) Dubovsky,"Electroconvulsive therapy," 2129-2140.

(34.) Ibid, 2133.

(35.) Ibid.

(36.) H A Sackeim et al, "Effects of stimulus intensity and electrode placement on the efficacy and cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy," The New England Journal of Medicine 328 (March 25, 1993) 839-846.

(37.) Fitzsimons, Mayer, "Soaring beyond the cuckoo's nest: Health care reform and ECT," 12.

(38.) Dubovsky, "Electroconvulsive therapy," 2130.

(39.) Kradecki, Tarkinow, "Erasing the stigma of electroconvulsive therapy," 87.

(40.) Fitzsimons, "Electroconvulsive therapy: What nurses need to know," 16.

(41.) "Transition to outpatient care accelerates," MedPro Month 5 (August 1995) 140.

(42.) C M Swartz, R Abrams, ECT Instruction Manual, fifth ed (Lake Bluff, Ill: Somatics, Inc, 1994) 1070.

(43.) Sackeim et al, "Effects of stimulus intensity and electrode placement on the efficacy and cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy," 839-846.

(44.) H A Sackeim, "Magnetic stimulation therapy and ECT," (Commentary) Convulsive Therapy 10 (April 1994) 255-258.

Susan M. Irvin, RN, C, MSM, CS, CNA, CAPA, is the program coordinator, ambulatory surgery unit, and supervisor, outpatient surgical clinics, at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Memphis.

The opinions or assertions contained in this article are the private views of the author and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The author wishes to acknowledge the support and assistance of Faye Robertson, RN, CS, clinical specialist in the mental hygiene clinic at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Memphis.

COPYRIGHT 1997 Association of Operating Room Nurses, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group