Fibromyalgia - a syndrome of musculoskeletal aches and pains - has been reported in 5 to 6 percent of patients attending general medicine and family practice clinics and may be present in up to 5 percent of the general population.[1] Fibromyalgia has been variously referred to as "fibrositis," "fibromyositis," "myofascial pain syndrome" and "psychogenic rheumatism,"[2] as well as "generalized tension myalgia," "generalized nonarticular rheumatism" and "generalized soft tissue rheumatism."[3] However, consensus by the American College of Rheumatology 1990 Multicenter Criteria Committee endorses the term "fibromyalgia."[4]

The committee also suggested abolishing the distinction between primary fibromyalgia, occurring in the absence of another condition, and secondary, or concomitant, fibromyalgia, which occurs in the presence of another disorder. A diagnosis of fibromyalgia alone remains valid, regardless of other diagnoses. Although fibromyalgia often occurs in association with other rheumatic disorders, which must be included in the differential diagnosis, each disorder must be managed separately.

Fibromyalgia has been defined as "nonarticular rheumatism with widespread and chronic musculoskeletal aching or stiffness associated with soft tissue tenderness at multiple, characteristic sites, in the absence of an underlying cause"[5] (Figure 1). Most patients are women between the ages of 20 and 50,[6,7] although fibromyalgia has been described in adolescents and the elderly.[8-10] The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Multicenter Criteria Committee reported that the disorder occurs at a mean age of 49 years.[4]

Problems with the classification and diagnosis of fibromyalgia have led to the development of criteria that apply to the old terminology of primary and secondary syndromes and also provide standardized, reliable and valid classification criteria.[4] The current American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for fibromyalgia are listed in Table 1. Using these criteria, fibromyalgia can be diagnosed with a sensitivity of 88.4 percent and a specificity of 81.1 percent.[4]

The diagnostic criteria that have been proposed for chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia overlap in many areas. In one study, a comparison of 27 patients with chronic fatigue syndrome and 20 patients with fibromyalgia revealed that patients with chronic fatigue syndrome who had pain at the time of the study had tender point scores identical to those of patients with fibromyalgia.[1] The authors also found that severe fatigue and/or sleep disturbance were present in more than 90 percent of patients in both groups. In the patients with fibromyalgia, 54 percent reported recurrent pharyngitis and 52 percent thought their symptoms began with a flu-like illness, characteristics that are more typical of chronic fatigue syndrome than fibromyalgia. One explanation for these findings may be that patients with fibromyalgia are seldom questioned about fever, swollen lymph nodes and sore throat, while patients with chronic fatigue syndrome are seldom examined for the presence of tender points.[18,22]

Despite many similarities, fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome differ in that specific musculoskeletal symptoms and signs are required for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia, while severe debilitating fatigue is a major criterion for the diagnosis of chronic fatigue.

Treatment

Treatment of fibromyalgia can be difficult for both the physician and the patient. Many different pharmacologic agents have been tried, as well as a number of nonpharmacologic modalities. No single treatment method has been shown to be completely effective and combinations of therapies are often used to relieve the symptoms of fibromyalgia.

PHARMACOTHERAPY

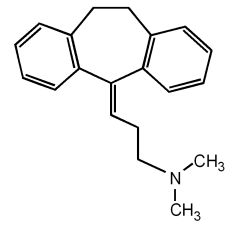

Tricyclic antidepressants are widely used in the treatment of intractable pain disorders. These agents offer various benefits, including antidepressant effects, anti-inflammatory properties, effects on central skeletal muscle relaxation and enhancement of pain-inhibiting factors through both serotonergic and noradrenergic pathways.[23] The major pharmacologic action of tricyclic antidepressants appears to be facilitation of central monoamine transmission by inhibiting serotonin and norepinephrine uptake at the synapse, thereby potentiating neuronal activity.[8,23]

One double-blind placebo-controlled study indicated that amitriptyline (Elavil, Endep) produced a significant improvement in local pain, stiffness and sleep pattern, but had little effect on fibrositic point tenderness.[24] The dosage in this study consisted of 10 mg daily for the first week, 25 mg daily for the next three weeks and then 50 mg daily for five weeks, all given at bedtime.

A similar placebo-controlled study used amitriptyline, 25 mg daily, and naproxen (Anaprox, Naprosyn), 500 mg twice daily, separately and in combination.[25] The findings in this study revealed that patients taking amitriptyline had improvement in pain, sleep difficulties, fatigue on awakening and tender point scores. Patients receiving combination therapy had no significant improvement in pain, compared with patients taking amitriptyline alone. Naproxen was not effective as a single agent. An amitriptyline dosage of greater than 50 mg daily has not proved to be of additional clinical benefit, and anticholinergic side effects are increased with this amount.[23]

Several studies have assessed the beneficial effects of cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril) in patients with fibromyalgia.[26-28] Cyclobenzaprine is a tricyclic drug, structurally similar to amitriptyline and with similar side effects. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of 120 patients with fibromyalgia evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of cyclobenzaprine. Patients randomly received 10 to 40 mg of cyclobenzaprine or placebo during the 12-week study. The patients receiving the drug reported significant improvement in local pain, sleep patterns and number of tender points compared with those taking placebo.[28]

NONPHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Other means of therapy used in the management of fibromyalgia include patient education, reassurance and exercise. Patient education is important in assuring patients that they have a common, nonthreatening condition and that little will be gained by seeing multiple physicians and undergoing repeated tests. Block[3] stresses the importance of gaining the patient's confidence: "This effort takes time and patience, but if the patient can be convinced of the diagnosis and the suitability of the proposed therapy, then the chance of success is much greater and the time required by the patient lessens at subsequent visits . . . The discussion . . . should encompass not only how the diagnosis has been made and what the condition represents, but also the entire therapeutic plan, for the patient will become a participant in selecting an acceptable regimen. The discussion is critical."

Patients may tend to be resistant to change because it implies adjustment, discomfort and effort. Familiar patterns seem safer than new ones, even when there is potential for benefit. The more that patients understand the condition, the better they will be able to help themselves. Individualized programs can be devised in which the patient and family members assume an active role in treatment.

Exercise is helpful as a treatment modality in patients with fibromyalgia. While the absolute advantages of exercise are not clear, research is ongoing and may clarify physiologic and psychologic benefits.

One randomized study included 42 patients with fibromyalgia who were assigned to a 20-week program consisting of either cardiovascular fitness training or simple flexibility exercises that did not lead to enhanced cardiovascular fitness.[29] Blind assessments were made, and patients who received cardiovascular fitness training showed significantly improved cardiovascular fitness scores compared with those who received flexibility training. Logistic regression analysis showed clinical and statistically significant improvement in pain threshold scores among patients in the cardiovascular training group. These patients also improved significantly in both patient and physician global assessment scores.

Another study evaluated patients with fibromyalgia for hypermobility of joints.[30] The 210 patients in the study received instructions about performance of an exercise program. Patients who exercised during the study showed improvement, but patients with fibromyalgia who had articular hypermobility were more likely to exercise with resultant improvement in symptoms.

Research has indicated that more than 80 percent of patients with fibromyalgia are not physically fit as assessed by maximal oxygen uptake and by xenon-133 clearance studies showing decreased blood flow in exercising muscle.[31] Study results have suggested a "detraining phenomenon," which can lead to habitual inactivity with a resultant common symptom complex that includes palpitations, tachycardia, dizziness, headache, paresthesias, breathlessness, chest pain, abdominal pain, dysphagia, muscle pain, tremor, excessive sweating, fatigue, weakness, tension and anxiety.[31-33]

Virtually all patients with fibromyalgia experience some degree of pain following initial exercise and as a result are reluctant to continue an exercise program, thus leading to further deconditioning.[32] Furthermore, unconditioned muscles are subject to postexercise muscle soreness, which includes muscle pain, stiffness, tenderness and reduced strength 24 to 48 hours after exercise.[31] This phenomenon may also reinforce the patient's belief that there is no way to control the disease, which in itself may perpetuate noncompliance with treatment regimens and encourage "doctor shopping."

Cinque[34] notes that "The key is to get people who aren't exercising into a simple, regular, not overly aggressive exercise program . . . the goal is to gradually condition them . . . if they start out doing too much too soon they become sore, tired, frustrated and eventually quit exercising." Thus, physicians should view exercise as an important component of therapy for patients with the fibromyalgia syndrome.

The Authors

DANIEL H. REIFFENBERGER, M.D. is in private family practice with the Brown Clinic in Watertown, S.D., and provides clinical care in a nearby rural health professional shortage area (HPSA) community. He is a graduate of the University of South Dakota School of Medicine, Sioux Falls, and completed a residency in family practice at the Sioux Falls Family Practice Residency program.

LOREN H. AMUNDSON, M.D. is professor of family medicine at the University of South Dakota School of Medicine, Sioux Falls, and medical director of the school's physician's assistant training program. Dr. Amundson received his medical degree from the University of Wisconsin Medical School, Madison.

Address correspondence to Loren H. Amundson, M.D., 1400 West 22nd Street, Sioux Falls, SD 57105-1570.

REFERENCES

[1.] Goldenberg DL, Simms RW, Geiger A, Komaroff AL. High frequency of fibromyalgia in patients with chronic fatigue seen in a primary care practice. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:381-7. [2.] Boulware DW, Schmid LD, Baron M. The fibromyalgia syndrome. Could you recognize and treat it? Postgrad Med 1990;87(2):211-4. [3.] Block SR. Fibromyalgia and the rheumatisms. Common sense and sensibility. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1993;19:61-76. [4.] Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:160-72. [5.] Yunus MB. Fibromyalgia syndrome: new research on an old malady. BMJ 1989;298:474-5. [6.] Goldenberg DL. Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges of fibromyalgia. Hosp Pract (Off Ed) 1989; 24:39-52. [7.] Semble EL, Wise CM. Fibrositis. Am Fam Physician 1988;38:129-39. [8.] Bennett RM. Nonarticular rheumatism and spondyloarthropathies. Similarities and differences. Postgrad Med 1990;87(3):97-9,102-4. [9.] Wolfe F. Fibromyalgia in the elderly: differential diagnosis and treatment. Geriatrics 1988;43:57-60,65,68. [10.] Yunus MB, Holt GS, Masi AT, Aldag JC. Fibromyalgia syndrome among the elderly. Comparison with younger patients. J Am Geriatr Soc 1988;36: 987-95. [11.] Goldenberg DL. Psychiatric and psychologic aspects of fibromyalgia syndrome. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1989;15:105-14. [12.] Caro XJ. Is there an immunologic component to the fibrositis syndrome? Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1989;15:169-86. [13.] Bengtsson A, Henriksson KG. The muscle in fibromyalgia - a review of Swedish studies. J Rheumatol Suppl 1989;19:144-9. [14.] Bennett RM. Fibromyalgia and the facts. Sense or nonsense. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1993;19:45-59. [15.] Russell IJ. Neurohormonal aspects of fibromyalgia syndrome. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1989;15:149-67. [16.] Yunus MB, Kalyan-Raman UP. Muscle biopsy findings in primary fibromyalgia and other forms of nonarticular rheumatism. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1989;15:115-34. [17.] Hench PK. Evaluation and differential diagnosis of fibromyalgia. Approach to diagnosis and management. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1989;15:19-29. [18.] Bennett RM. Confounding features of the fibromyalgia syndrome: a current perspective of differential diagnosis. J Rheumatol Suppl 1989;19:58-61. [19.] Wolfe F. Two muscle pain syndromes. Fibromyalgia and the myofascial pain syndrome. Pain Management 1990,3:153-64. [20.] Campbell SM. Regional myofascial pain syndromes. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1989;15:31-43. [21.] Calabrese L, Danao T, Camara E, Wilke W. Chronic fatigue syndrome. Am Fam Physician 1992,45:1205-13. [22.] Newman A. Are chronic fatigue, fibromyalgia the same entity? Family Pract News 1990;4(1-14):32. [23.] Satterthwaite JR, Tollison CD, Kriegel ML. The use of tricyclic antidepressants for the treatment of intractable pain. Compr Ther 1990;16(4):10-5. [24.] Carette S, McCain GA, Bell DA, Fam AG. Evaluation of amitriptyline in primary fibrositis. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:655-9. [25.] Goldenberg DL, Felson DT, Dinerman H. A randomized, controlled trial of amitriptyline and naproxen in the treatment of patients with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:1371-7. [26.] Quimby LG, Gratwick GM, Whitney CD, Block SR. A randomized trial of cyclobenzaprine for the treatment of fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol Suppl 1989;19:140-3. [27.] Hamaty D, Valentine JL, Howard R, Howard CW, Wakefield V, Patten MS. The plasma endorphin, prostaglandin and catecholamine profile of patients with fibrositis treated with cyclobenzaprine and placebo: a 5-month study. J Rheumatol Suppl 1989;19:164-8. [28.] Campbell SM, Gatter RA, Clark S, Bennett RM. A double-blind study of cyclobenzaprine versus placebo in patients with fibrositis [Abstract]. Arthritis Rheum 1986;27:76. [29.] McCain CA, Bell DA, Mai FM, Halliday PD. A controlled study of the effects of a supervised cardiovascular fitness training program on the manifestations of primary fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:1135-41. [30.] Goldman JA. Hypermobility and deconditioning: important links to fibromyalgia/fibrositis. South Med J 1991;84:1192-6. [31.] Bennett RM, Clark SR, Goldberg L, Nelson D, Bonafede RP, Porter J, et al. Aerobic fitness in patients with fibrositis. A controlled study of respiratory gas exchange and 133xenon clearance from exercising muscle. Arthritis Rheum 1989;32:454-60. [32.] Bennett RM. Physical fitness and muscle metabolism in the fibromyalgia syndrome: an overview. J Rheumatol Suppl 1989;19:28-9. [33.] Wagenmakers AJ, Cookley JH, Edwards RH. The metabolic consequences of reduced habitual activities in patients with muscle pain and disease. J Sports Sci 1988;6:239-59. [34.] Cinque C. Fibromyalgia: is exercise the cause or the cure? Physician Sportsmed 1989;17:181-4.

COPYRIGHT 1996 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group