In February, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Avastin (bevacizumab) for the treatment of advanced colorectal cancer. Avastin is an angiogenesis inhibitor. It works by targeting and inhibiting the functioning of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which stimulates new blood vessel formation. When bound by Avastin, VEGF can no longer stimulate the growth of blood vessels, thus denying tumors the blood, oxygen and other nutrients they need for growth. Avastin has been approved as a first-line treatment for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. It thus will be highly competitive with another newly approved drug, Erbitux, which only received approval as a last-ditch therapy for advanced stages of this disease.

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

Both Erbitux and Avastin are genetically engineered versions of a mouse antibody that contains both human and mouse components. Avastin is the first angiogenesis inhibitor ever approved to treat cancer. As such, it has generated a great deal of hope and excitement. It appears to work in accordance with a theory put forward 30 years ago by Professor Judah Folkman of Harvard, who suggested that by stopping the growth of new blood vessels one could stop the growth of cancer.

The FDA approved Avastin based on the results of a randomized, double-blind clinical trial of more than 800 patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Avastin was found to extend colorectal cancer patients' lives by 4.7 months, when given intravenously along with a standard chemotherapy regimen known as IFL (aka the 'Saltz regimen'). IFL includes the already-approved drugs irinotecan (Camptosar or CPT 11), 5-fluorouracil (5FU) and leucovorin. Patients who received IFL alone lived on average 15.6 months. Those who also got Avastin survived on average 20.3 months. The average time before tumors started re-growing, or new tumors appeared, was four months longer in patients given Avastin than in patients who received IFL alone. The overall response rate to the IFL/Avastin treatment was 45% compared to 35% for the control arm of the trial. There is no mention of any complete responses or cures. (Responses are significant tumor shrinkages that last for one month or more.)

These positive results with Avastin came as a surprise. Just last year, its prospects did not look particularly promising. A 2003 clinical trial at the National Cancer Institute, for example, found that there were no significant differences in overall survival between those getting high-dose Avastin, low-dose Avastin, and no supplemental Avastin at all. (Yang 2003)

Yet Mark B. McClellan, MD, PhD, the departing FDA Commissioner, apparently sees things in a very different light. Both Avastin and Erbitux have "significantly improved the armamentarium for fighting this disease," he claimed. "These medical achievements [are] ... making a real difference in the lives of cancer patients." (FDA News, 2004)

Serious Side Effects

Angiogenesis inhibitors have been widely hailed as a benign form of treatment. According to an interview with Dr. Folkman, "... unlike chemotherapy, angiogenesis inhibitors will be used on a long-term basis for two important reasons: they will not generate drug resistance and they will be non-toxic." (Folkman, 2004)

However, in the current trials treatment with Avastin plus chemotherapy had many adverse consequences. At Genentech's website, www.avastin.com, the company states that "administration can result in the development of gastrointestinal perforation as well as wound dehiscence, in some instances resulting in fatality." (Dehiscence is the rupture or splitting open of a surgical wound, or of an organ or structure.) With Avastin, such perforations are sometimes associated with the formation of abscesses in the bowel. According to the FDA, this may be accompanied by internal bleeding. The incidence of this type of severe adverse event was 2%.

High Blood Pressure Crises

The Genentech website further states that "serious, and in some cases fatal, hemoptysis has occurred in patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy and Avastin." Hemoptysis is the expectoration of blood or of blood-streaked sputum from the larynx, trachea, bronchi, or lungs. "In a small study," it continues, "the incidence of serious or fatal hemoptysis was 31% in patients with squamous histology (the microscopic structure of tissues, ed.) and 4% in patients with adenocarcinoma receiving Avastin...."

In the clinical trials just announced, the treatment was associated with high blood pressure in 60% of patients. In 7% this hypertension was severe enough to constitute a crisis (with a cuff reading of more than 200/110 mmHg), requiring emergency treatment. Despite palliative treatment, however, the hypertension was found to be long-lasting in a majority of cases. "Four months after discontinuation of therapy, persistent hypertension was present in 18 of 26 patients that received bolus-IFL plus Avastin and 8 of 10 patients that received bolus-IFL plus placebo." (A 'bolus' is a single relatively large dose of a drug.) In other words, the company is suggesting that severe hypertension is caused more by the IFL than by Avastin itself.

There have indeed been serious concerns in the past over the toxicity of IFL. In 2001, for instance, two prominent clinical trials were suspended because the death rate on the Saltz regimen (i.e., IFL) was elevated. (Goldberg 2001)

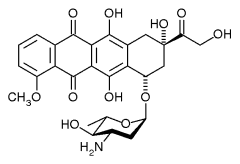

Another serious danger with the Avastin/IFL regimen is congestive heart failure (CHF), which was reported in 22 of 1,032 (2%) patients receiving Avastin in these trials. CHF occurred in an even higher percentage--six out of 44 (14%)--of patients who received Avastin along with the common anthracycline drugs, such as Daunorubicin, Doxorubicin (Adriamycin), Epirubicin, and Idarubicin, all of which are known to have cardiotoxic effects in their own right. Congestive heart failure occurred in 13 of 299 (4%) of patients who had previously received anthracyclines and/or left chest wall irradiation.

Other side-effects included kidney damage, weakness, abdominal pain, headache, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, mouth sores, constipation, upper respiratory infection, nosebleeds, difficulty breathing, peeling skin, and protein in the urine. (The company does not provide any statistics concerning the frequency of these side effects.)

Paucity of Data

Traditionally, publication has been considered an essential part of the scientific method. Approval of a new drug or the adoption of a new treatment has until recently been based on the outcome of rigorously designed clinical trials, the results of which had to be submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals. Once results were published in this way, other scientists had an opportunity to attempt to reproduce them. Only when this protracted process had been completed was a treatment considered ready for final regulatory approval by the Food and Drug Administration.

Today, however, new clinical information is frequently hoarded and closely guarded as a trade secret. The data I have cited above comes not from peer-reviewed studies in medical journals, but from the websites of the FDA and Genentech, the manufacturer of the drug Avastin. No individual authors are listed, no publication citations given. If you try to find independent data on Avastin you will probably be disappointed, as I was. For instance, PubMed is the universally respected repository of scientific references, abstracts and journal links. Although a search of PubMed turns up 36 items on Avastin, only two of these are categorized as randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The present Genentech studies are not among them. As with Erbitux, the data on which FDA approval was based was only made available for evaluation to a select group of individuals who were hand-picked by an FDA that is increasingly compliant to the wishes of Big Pharma. To my knowledge, the broader scientific community has never had a chance to see, peer-review or critique these results before the agent was released to the market.

Societal Implications

Yet the financial and societal implications of approving Avastin are, well, vast. Sales are expected to reach $2 billion per year or even more, according to the New York Times (Pollack 2004). In fact, this estimate may be on the low side because FDA's approval was worded in such a way as to allow doctors to use the drug more liberally than expected.

Coming on the heels of the earlier approval of Eloxatin (oxaliplatin), doctors treating colorectal tumors now have a confusing array of choices. "We have too many agents; we don't know how to mix them together in the right order," complained Dr. Louis Fehrenbacher, an oncologist with the Kaiser Permanente hospital group. "But," he added, "that's an awfully nice luxury to have, because five years ago we didn't have much."

One thing is certain: these new agents will tremendously increase the cost of treating colorectal cancer, at a time when both society and individuals can ill afford such an increase. "This will certainly be reflected in the cost of health care at the end of the year," said Dr. Heinz-Josef Lenz, a colon cancer expert at the University of Southern California. Genentech, which lost no time in shipping Avastin, will charge about $4,400 per month for the new drug. Data from clinical trials suggest that it will be used for about 10 months (the expected survival time of patients who take it), thereby adding another $44,000 to the medical bill of the average colorectal cancer patient.

"We think it's a fair price, and we think our customers will see it that way," said Ian Clark, a senior vice president at Genentech, which manufactures the drug. One wonders, since $44,000 is equal to the annual gross income of the average American household ($43,057 in 2002). The cost for the competing new drug Erbitux will be $10,000 a month, but Erbitux will probably be used for shorter periods of time because it was approved as a last-ditch treatment (Pollack 2004). It will be morally difficult for insurance companies to deny patients drugs that might increase their survival by a few months. On the other hand, patients are unlikely to be cured and the annual cost to society will soar to the tune of billions more dollars. And this estimate does not include the increased cost of treating some of the side effects of these new regimens. Meanwhile, since Avastin's meteoric rise, the stock of its manufacturer, Genentech, has more than tripled in value.

Alternative Treatments?

Almost from the beginning of interest in the role of angiogenesis (the induction of new blood vessel formation) in cancer, there have been suggestions that natural substances might achieve the same ends as these patented products, and at a fraction of the cost. This is a topic that would require a separate newsletter.

Shark cartilage was originally proposed as an anticancer agent precisely because of its inhibitory effect on blood vessel formation (Lane 1992). Author John Boik in his outstanding book, Natural Compounds in Cancer Therapy (2001), has identified a number of natural compounds that could play a role in reducing tumor angiogenesis. The following agents, for example, have been shown in animal or test-tube experiments to reduce new blood vessel formation:

* Anthocyanidins and proanthocyanidins

* Butcher's broom

* Horse chestnut

* Vitamin A and D3

* Anticopper compounds (including alpha-lipoic acid)

* Green tea catechins (such as EGCG)

* Resveratrol (found in red wine)

Retired USDA herbalist James Duke, PhD, has estimated that a potentially useful anti-angiogenic "cocktail," composed of natural substances could be put together for about $1 per day. Of course, these compounds have generally not been thoroughly tested in humans, whereas Avastin has now been proven to work, in randomized trials. While technically true, this evades the central issue. As Dr. Duke has asked, what are the chances of the medical establishment ever carrying out head-to-head tests of a $300-400 a year natural regimen vs. this $44,000 per year drug? We hear so much glib talk about cost cutting, that an observer might logically conclude that medicine would strongly favor the vigorous investigation of inexpensive approaches. But this is not the case. There is in fact little incentive for pharmaceutical companies to find the least expensive (and least toxic) approaches. And Big Pharma still rules the roost. In our topsy-turvy world, inexpensive approaches to cancer stand little chance of getting tested, much less being accepted, by this drug-oriented society.

[c]2004 Ralph W. Moss, PhD. All Rights Reserved

References

Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves First Angiogenesis Inhibitor to Treat Colorectal Cancer, February 26, 2004.

Folkman. Judah: Inventing the future. Retrieved March 1, 2004 from: http:// www.biospace.com/articles/010600_Judah.cfm

Goldberg, Kirstin. Deaths on Saltz regimen prompt groups to suspend accrual on colon cancer trials. The Cancer Letter, Vol. 27, No. 19, May 11, 2001.

Kabbinavar F, Hurwitz HI, Fehrenbacher L, Meropol NJ, Novotny WF, Lieberman G, Griffing S, Bergsland E. Phase II, randomized trial comparing bevacizumab plus fluorouracil (FU)/leucovorin (LV) with FU/LV alone in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Jan 1;21(1):60-5.

Lane, I. William, Comac, Linda, Sharks Don't Get Cancer. New York: Avery Penguin Putnam, 1992.

Pollack, Andrew. FDA Approves cancer drug from Genentech. New York Times, February 27, 2004.

Yang, JC, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003 Jul 31;349(5):427-34.

by Ralph W. Moss, PhD, Director, The Moss Reports

800-980-1234 * www.cancerdecisions.com

COPYRIGHT 2004 The Townsend Letter Group

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group