Generics manufacturers strongly oppose the tactic

Since January 1997, DuPont Merck has battled unlimited substitution of Narrow Therapeutic Index medications, including its particular nemesis warfarin sodium, on several fronts in 23 states, with more to come.

In its efforts to require pharmacists to check with a physician before switching patients to a generic, the pharmaceutical giant has approached both pharmacy boards and state legislatures, and sometimes both.

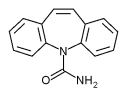

At issue is the future of the generic version of the popular anti-stroke drug, along with 23 other NTIs, including drugs to treat asthma, epilepsy, heart disease, hypertension and other maladies requiring calibrated and closely monitored doses with a narrow range of patient safety.

Not surprisingly, generics suppliers have a dim view of DuPont Merck's efforts. 'This is a systematic effort on the part of DuPont Merck to preserve their monopoly in Coumadin," charged Bruce L. Downey, chief executive of Barr Laboratories, maker of warfarin sodium, Downey has been following DuPont Merck from state to state in an effort to counteract the drug maker's tactic.

"They've done everything they can," Downey said, including "petitioning the Food and Drug Adminstration to change the standards--on the grounds of very shaky science, in my opinion. Then, they tried to get the release specs changed, again on the grounds of trumped-up science. Then, they've gone to the state formulary boards and legislatures."

While several attempts have been made to introduce a reliable generic to Coumadin, Barr Laboratories is now mounting a full-scale offensive on DuPont Merck's $500-million-a-year Coumadin market.

Robert W. Perkins, DuPont Merck's vice president for public policy, couched the argument in patient safety terms. "The question the patient is asking is, 'What happens at the pharmacy? Am I getting brand-name or generic?' To be honest, most of the time it doesn't matter. Generics undergo rigorous testing, but, in the case of NTIs, you need to be more careful. If you take too much Coumadin, you can bleed to death."

DuPont Merck took these arguments to the FDA and United States Pharmacopeia, where it failed to limit substitution of generics. In April 1997, in fact, in a letter to the National Boards of Pharmacy in Park Ridge, Ill., Roger L. Williams, M.D., deputy center director for pharmaceutical science for the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, reiterated the FDA's stance that NTI drugs are therapeutically equivalent to name brands and "can be substituted with the full expectation by the patient and physician that they will have the same clinical effect and safety profile as the innovator drug."

"Generics used to have 30 percent of the market," explained Charlie Mayr, Barr Labs' director of communications. "Now, they can capture 80 percent of the market in 90 days. If the branded companies can't protect their product any other way, they will fight to extend the patent, then they will try to keep the generic off the market by trying to change the FDA's standards. Failing that, they will try to raise barriers to substitution as they are doing with warfarin."

Taking it to the states

Since early 1997, DuPont Merck Company, maker of the anti-coagulant Coumadin, has taken its fight against warfarin sodium, the generic version, to the states.

"They want to create a barrier at the pharmacy desk," said Mayr. "Pharmacists and physicians are too busy to make and take calls. Substituting the generic may become more difficult. Besides, physicians already have the right to request no substitutions."

"Make that when a generic is substituted on a refill," stressed Perkins. "The physician can direct the pharmacist not to substitute on the original prescription, but then he or she might substitute on the refill, without the patient or physician knowing. For that matter, we don't think a patient on a generic should be switched to a branded drug without a call, or even to a different version of the generic."

With generic prices running 30 percent to 40 percent of branded prices, the financial stakes for both managed care and Medicaid patients (and thus state coffers) could be substantial if barriers to substitution were erected.

"This issue affects the lives of literally hundreds of thousands of patients throughout New York who take NTI drugs for asthma, high blood pressure, epilepsy, depression and stroke prevention," remarked one physician in the Empire State.

Based on 1996 figures assembled by Thomas McLaughlin, D.Sc., of the Harvard Medical School, the Pennsylvania Pharmaceutical Assistance Contract for the Elderly program would have to shell out an additional $5.8 million for Medicaid and PACE prescriptions if access to generics were limited.

This far, bills requiring additional pharmacist checks have passed into law in North Carolina, Texas and Virginia

In North Carolina, the statute took effect on July 1, 1997, and required the board of pharmacy to develop a list of NTI products to be restricted; the list is due out after January 1998. In Texas, the law went into effect Sept. 1, 1997; the pharmacy board there expects to appoint a task force sometime next spring. And, in Virginia, the law takes effect next July; warfarin sodium is on the formulary and the board is reluctant to create special rules.

In New Jersey, warfarin sodium was approved for sale with a non-binding recommendation that pharmacists inform patients when switching them to the generic. Melanie Willoughby, executive director of the Trenton, N.J.-based New Jersey Council of Chain Drug Stores, representing 25 chains and 750 pharmacies, reiterated that Coumadin and war-farm sodium are bioequivalent.

"New Jersey's Drug Utilization Review Council approved warfarin sodium," she said, "So, what's the problem? Who's harmed?" Apparently satisfied for the time being with the regulatory fix, the New Jersey state legislature canceled a hearing and has delayed action.

Dueling studies

No war would be complete without skirmishes behind the lines. Both sides have marshaled studies on the effectiveness and side effects of branded vs. generic. Predictably, each also has attacked the other's findings.

Barr Labs released one observer-blind, randomized, crossover study utilizing the two forms of warfarin sodium, branded and unbranded, involving 39 patients with atria defibrillation who were kept on constant doses of the two formulations. The company claims the outcomes showed the two drugs were bioequivalent within specified norms and demonstrated no differences in side effects.

DuPont Merck subsequently attacked the methodology of the study, as well as promotional materials issued by Barr Labs. DuPont Merck also asked the FDA to make Barr change its promotional literature, which was eventually done. DuPont Merck also sent the FDA more than 70 adverse reaction reports on warfarin sodium that, it said, had spontaneously come to its attention.

In another firefight, the FDA admonished DuPont Merck for its allegations of non-bioequivalence of warfarin sodium, saying, "It is misleading to suggest that generic products that the FDA has determined are bioequivalent to Coumadin may not be therapeutically equivalent to the reference product ... The information supplied by DuPont is not persuasive and does not support its claims."

The fight for generics

The all-out, state-by-state effort to require physician consultation on generic NTI substitutions is unprecedented, according to experts.

"We understood there would be marketplace resistance when we launched," Mayr said of Barr's generic warfarin sodium product. "We put $5 million behind our launch, setting up 800 numbers with nurses and continuing medical education programs for doctors and pharmacists. We have supported this at the level of a branded product."

This may signal a change in the generic industry. "The way substitution works," Mayr said, "we have traditionally not had large marketing departments. We used to take out a couple of ads in the trades. We have not even had government affairs offices. We have people in Washington now."

Efforts by the generic manufacturers are augmented by the Generic Pharmaceutical Industry Association and National Pharmaceutical Alliance, both based on the capital. G. Thomas Long, legislative counsel for the NPA, does not see DuPont Merck's initiatives as a precursor of a blanket attack on generics.

"These efforts are driven by individual company needs," he said. "They use all sorts of strategies. Citizen petitions to the FDA. Challenges to the way the FDA evaluates applications. Anything to delay. Six months can cost people money. All they [DuPont Merck] have to do in this fight is win over one or two big states to hurt the generic companies and one or two small states to pay for their campaign. They have to cut off warfarin sodium's market penetration before people discover the two drugs are exactly the same.

"At some point," he added, "it won't be worth DuPont Merck's time, but that day hasn't come."

As framed, the state proposals apply the restrictions on substitutions to all 24 NTIs. Mark Goscko, senior director of scientific affairs of Teva Pharmaceuticals USA in Sellersville, Pa., is concerned about his company's generic NTI drug, carbamazepine (marketed under the branded name of Epitol), which is taken by more than a quarter of patients requiring the anti-convulsant.

Teva testified at the New Jersey Drug Utilization Review Council and participates in all industry meetings on generic substitution. "Up until this [warfarin] issue surfaced," Goscko said, "half the market [for carbamazepine] had converted to generic. It was not a problem. By challenging the interchangeability of an entire class of drugs, DuPont Merck has made it more of a health issue. Next year, this will resurface."

"Oh, yes," vowed DuPont Merck's Perkins, "It will be a hell of a fight."

COPYRIGHT 1998 Lebhar-Friedman, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2000 Gale Group