Broken bones don't end in childhood. According to the Surgeon General:

* Four out of 10 white women age 50 or older will break a hip, spine, or wrist during their lives.

* Nearly one in five hip fracture patients ends up in a nursing home within a year.

* By 2020, half of all Americans over age 50 will be at risk for fractures from weak bones.

Roughly 10 million Americans over age 50 have osteoporosis. Another 34 million have osteopenia--bone density that's lower than normal, though not quite low enough to be called osteoporosis.

"The bone health status of Americans appears to be in jeopardy, and left unchecked it is only going to get worse as the population ages," says the Surgeon General.

How can you protect your bones? Many people know that they need to get enough calcium. Some also exercise and take vitamin D. But researchers now believe that you can do more.

RELATED ARTICLE: Blame it on estrogen.

As women go through menopause, most lose bone rapidly. Unless they take estrogen, the drop-off in hormone levels triggers a breakdown in bone.

"It's the downward adjustment caused by estrogen loss," says Bess Dawson-Hughes of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Jean Mayer Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University in Boston. A decline in estrogen also weakens bone in men as they age, though less dramatically.

No one can avoid all the loss. "You can mitigate it, but you can't obliterate it," says Dawson-Hughes. "People could maybe cut it by a third with calcium, vitamin D, and exercise."

Can anything else help?

"Many people know a lot about calcium and vitamin D, but we're finding a whole spectrum of other nutrients that protect bone," says Tufts researcher Katherine Tucker.

"People think of bone as static. In fact, it's always being broken down and rebuilt, and that process is sensitive to a delicate balance of nutrients."

How much bone do women lose during menopause?

"You lose rapidly--about three percent per year--from sites such as the spine," explains Dawson-Hughes. "For peripheral sites like the arm or hip, you lose at a lower rate--about one percent per year."

Four to eight years after menopause begins, the bone loss slows. "It drifts down to an average of one percent per year," says Dawson-Hughes.

Men go through only the slower phase. Their bodies also make estrogen, though much less than testosterone. Levels of active estrogen and testosterone drop with age.

In both men and women, a decline in estrogen makes the intestine and kidneys absorb less calcium and signals bone to slow construction and speed up demolition (see "Super Remodel," p. 7).

"It's always a balance between bones building up and breaking down," says researcher Lynda Frassetto of the University of California, San Francisco. "As you get older, the balance tips towards breaking down."

Calcium & Vitamin D

In 1992, researchers reported that elderly French women who were given calcium and vitamin D for 1 1/2 years had 43 percent fewer hip fractures than similar women who took a placebo. (1) And in 1997, U.S. researchers found higher bone density and fewer fractures in older men and women who were given calcium and vitamin D instead of a placebo. (2)

"If you're not getting enough calcium and vitamin D, your bones break down to supply calcium to the rest of the body," explains Frassetto.

It's not clear how much of the benefit is due to calcium and how much to vitamin D, which helps the body absorb calcium. But to most health authorities, that's not a pressing question.

"It may not be realistic to try to dissect the individual contributions of calcium, vitamin D, and physical activity on bone health," says the Surgeon General, "since they all need to be optimized."

So far, they're not, at least for most Americans. And the deficits build up.

"A negative balance of only 50-100 mg of calcium per day over a long period of time is sufficient to produce [osteoporosis]," cautions the Surgeon General.

The typical woman consumes 800 milligrams of calcium a day (from food and supplements), while recommended levels range from 1,000 mg (for women aged 19 to 50 to 1,200 mg (for women over 50).

It's tougher to gauge how much vitamin D people get, since some comes from exposure to sunlight. But it's clear that the vitamin's role is crucial.

"Small intervention trials showed that vitamin D lowered the risk of falling," says Dawson-Hughes. When researchers pooled the trials--on more than 1,200 older people--they found a 22 percent drop in risk. (3)

That's one of several clues that vitamin D strengthens not just bone but muscle. For example, in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, older people with higher vitamin D levels in their blood performed better on tests of leg strength.

"They do better on tests that measure how long it takes to get out of a chair and how long it takes to walk eight feet," says Dawson-Hughes.

Another clue: muscles have "receptors" for vitamin D. "Several studies indicate that muscle fibers respond to activation of the vitamin D receptors by getting larger," she explains.

The latest evidence on vitamin D has led many researchers to call for raising the recommended levels (400 IU a day for people 51 to 70 and 600 IU for those over 70).

"If you look at bone mass, lower extremity muscle performance, and the risk of falling--all of which influence fracture risk--and then you look at fracture intervention trials," says Dawson-Hughes, "you come up with the sense that anyone over 60 needs about 1,000 IU of vitamin D a day."

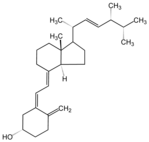

That level assumes that people get vitamin D3 (cholecalciferol), which has a greater impact on bone density and raises blood levels of vitamin D for a longer period of time than vitamin D2 (ergocalciferol). (4,5) Experts estimate that D3 is at least three times more potent than D2.

"Until recently, there was no suggestion that it made a difference," says Dawson-Hughes. Most supplements and foods (except fortified soy milks) use D3 (see "Good Day Sunshine"). Ingredient lists on labels don't have to say which vitamin D has been added, but most do.

Vitamin K

"People in the lowest quarter of vitamin K intakes have a significantly higher risk of hip fracture," says Tufts researcher Sarah Booth.

In one study, older men and women who consumed at least 254 micrograms (mcg) a day of vitamin K were 65 percent less likely to have a hip fracture over the next seven years than similar people who typically consumed no more than 56 mcg a day. (6)

Researchers think they know why K is crucial. "The production of the bone matrix is dependent on vitamin K," says Dawson-Hughes.

The bone matrix consists largely of a protein called osteocalcin. Bone-building cells called osteoblasts lay down the osteocalcin. When the matrix gets mineralized, it becomes bone.

"So if you're vitamin-K-deficient, you don't get as much bone matrix or as much bone," says Dawson-Hughes. A recent study from the Netherlands offers the strongest evidence so far that vitamin K matters. Researchers randomly assigned 155 healthy postmenopausal women to take one of three daily pills: a placebo; a supplement containing calcium (500 mg), vitamin D (320 IU), zinc (10 mg), and magnesium (150 mg); or the same supplement plus vitamin K (1,000 mcg). (7)

After three years, "there was significantly less bone loss in the group getting vitamin K" than in the other two groups, notes Booth.

The current recommended vitamin K levels are 90 mcg a day for women and 120 mcg a day for men. But those are based on how much vitamin K the body needs to help blood clot, not to keep bones strong.

How much vitamin K is enough for bones? "We know that 100 mcg a day is too low and 200 mcg a day is better, but we don't really know how much is optimal," says Booth.

Researchers should know more in a year or two. "Three clinical trials are under way in the U.S.," says Booth. "They're using different doses and they'll all be finished by late 2006." The Tufts trial, for example, is giving 500 mcg a day, a fairly high dose.

In the meantime, the simple solution is to eat more vegetables. "If you eat a variety of vegetables, you can easily get enough vitamin K," says Booth (see "The Green Vitamin").

"Older people typically have higher intakes," she notes. "It's the 20-to-40-year-olds who get less. A tiny stalk of broccoli on your pizza isn't enough."

Some multivitamins and some calcium supplements (like Viactiv) supply vitamin K (and vitamin D), but others don't, in part because vitamin K can interfere with blood-thinning drugs like warfarin (Coumadin). People on those drugs shouldn't take vitamin K without checking with a physician.

Protein

Is protein good or bad for your bones?

Some scientists argue that protein robs the body by making the kidneys excrete more calcium. But others find that elderly people who have had a hip fracture gain more bone if they're given a protein supplement.

The answer may depend on how much calcium you get.

Dawson-Hughes gave a daily placebo or supplement containing calcium (500 mg) plus vitamin D (700 IU) to 342 men and women aged 65 or older for three years. When researchers divided them into thirds according to protein intake, those who averaged 89 grams a day had less bone loss than the groups that averaged 79 grams of 72 grams a day. However, that was true only in people who took the calcium plus vitamin D. (8)

"If people were in the placebo group, bone mass drifted down as protein intake rose," she explains.

Why would protein's impact depend on calcium?

"Protein stimulates the production of a bone growth factor called IGF-1," says Dawson-Hughes. IGF stands for insulin-like growth factor. "People who don't have much IGF are going to have lower bone--and probably muscle--mass," she adds.

But protein has a downside for bone.

"Protein also promotes urinary calcium excretion," says Dawson-Hughes. So eating more protein means you lose more calcium in your urine.

"Our hypothesis is that if you have a calcium intake that's adequate to offset that wasting through the kidney, maybe you can tip the balance towards bone growth."

Fruits & Vegetables

Some studies find denser bones in older people who consume more fruits and vegetables. (9) Why? They may protect bones by making the urine more alkaline.

"Like people in other industrialized countries, Americans eat more foods that produce acid than alkali," explains the University of California's Lynda Frassetto.

That's because our diets are high in grains (like bread, pasta, rice, and baked goods) and protein foods (meat, poultry, and seafood), which generate acid residues, and low in fruits and vegetables, which produce alkali. (Milk is neutral.)

"Too much acid is bad for the system, so the body spends a lot of time and effort to get rid of it," explains Frassetto. That means neutralizing, or buffering, the acid with an alkali.

"The biggest reservoir of alkali in the body is bone," says Frassetto. "So the body dissolves the mineral structure of bones to neutralize the acid" with an alkali like calcium bicarbonate.

The body may also buffer acid by breaking down muscle. That releases ammonia (an alkali), which may pick up some acid on its way out of the body.

"Muscle breakdown may also enable the kidney to dump acid," says Dawson-Hughes. "Eat more fruits and vegetables and you don't have the acid-load problem."

Potassium

Fruits and vegetables are packed with potassium. Is that why they seem to protect bones?

"We don't know if it's potassium that really matters and the fruits and vegetables are just going along for the ride," says Dawson-Hughes. "Studies on both sides are convincing."

But research on potassium is easier to do. For example, Frassetto's team recently gave 170 postmenopausal women either potassium bicarbonate or a placebo for up to three years. (10) (Each woman also got 400 IU of vitamin D and enough calcium to bring her intake up to 1,200 mg a day.)

"The more potassium they got, the less calcium they excreted," she says. "And potassium had the biggest effect in the women who were losing the most calcium."

Frassetto is also looking at potassium's impact on bone density, but her results are not yet available. In the meantime, she recommends fruits and vegetables, not supplements.

"We don't have the data to know how much people should take," she explains. More importantly, "there's a subset of people who shouldn't take potassium because they have trouble getting rid of it."

That includes those who take medications that hinder potassium excretion (like the diuretics Aldactone, Midamor, and Dyrenium) and those--especially diabetics--who have impaired kidney function. "Many people don't know they have kidney problems," adds Frassetto.

Too much potassium from supplements is dangerous. "It causes heart arrhythmias," she notes. "Potassium is sometimes used to kill people by lethal injection."

Fruits and vegetables, in contrast, are not only safe, but they're good for you.

"They're high in fiber and antioxidants and you can eat them instead of all the garbage that people eat," says Frassetto.

Vitamin A

It's not too little vitamin A, but too much, that can put bones at risk.

In a study of 72,000 postmenopausal women, those who got the most vitamin A from retinol (at lest 6,660 IU a day) in foods or supplements had nearly double the risk of hip fracture compared to those who got the least vitamin A from retinol (less than 1,700 IU a day). (11)

"Overall, studies show a detrimental effect of vitamin A," says Tufts's Sarah Booth. "But some studies don't, so it's not conclusive. Still, many people are eating so much vitamin A and it's not conferring a benefit."

Vitamin A--called retinol--is found in liver and some dairy foods. But a far bigger source is multivitamins and fortified foods. "Some people aren't aware of all the sources, like breakfast cereals, energy bars, of Ensure," says Booth.

Beta-carotene, which is found in fruits, vegetables, and many multivitamins and fortified foods, is converted into vitamin A in the body. But that doesn't threaten bones.

Our advice: look for a multivitamin with no more than 2,000 or 3,000 IU of vitamin A from retinol. (The ingredient list should say vitamin A acetate or palmitate. Don't count any beta-carotene that the supplement may contain.)

And don't take two multivitamins a day to get a higher dose of vitamin D. "It's not a good idea because you'd be getting too much vitamin A and possibly other nutrients," says Dawson-Hughes.

Exercise

Strain is good.

The body constantly monitors how much strain muscles put on bone. More strain signals the body to build bone. Less strain sends a message to break down bone.

"Some people make bone loss worse by not doing enough exercise," says Frassetto. "If you sit around all day, you'll have weaker bones than if you're walking around and staying active."

In a study of more than 60,000 women aged 40 to 77, those who walked for at least four hours a week had a 40 percent lower risk of hip fracture than those who walked for less than an hour a week. (12)

Exercise builds more bone in youngsters, especially during puberty, when kids gain 25 to 30 percent of their bone mass. In middle-aged and older people, it's more a matter of slowing losses.

"In a one-year exercise program, you see about a one percent increase in bone density, while density drifts downward in the placebo [non-exercising] group," says Dawson-Hughes.

For older people, exercise is crucial because it lowers the risk of falling. On average, we lose five percent of our muscle mass every decade after age 30, and the loss accelerates after age 65. "By increasing strength and balance, you find fewer falls," adds Dawson-Hughes.

What's the best exercise? "It doesn't matter what you do as long as you're using bones to work against gravity," says Frassetto. That translates into almost any activity except swimming or bicycling.

"When you're swimming, the water holds you up so you're not working against gravity," she explains. "When you're bicycling, you're supported by the bike, so it's difficult to show that it builds bone density."

Other Factors

Several other factors affect bone, but to a lesser (or less certain) degree. Among them:

* Alcohol. It's a double-edged sword. "Heavy alcohol intake is a risk factor for osteoporosis," says Tufts University's Katherine Tucker.

"But smaller amounts--about one drink a day--are beneficial for women." (Researchers haven't studied men.)

Alcohol may strengthen bones because it raises estrogen levels. Estrogen may also explain why thin women have a greater risk of osteoporosis than overweight women. "Obesity raises estrogen levels," says Tucker.

"Unfortunately, that's the same reason why both alcohol and obesity increase the risk of breast cancer."

* Caffeine. "Caffeine has a weak negative effect, because it increases calcium excretion," says Dawson-Hughes. "But you can offset the loss by raising calcium intake. It's fairly minor, but everything makes a contribution."

* Magnesium. Like potassium, magnesium helps neutralize acid in the body. However, its effect on bone "isn't as clear cut as calcium's," says Dawson-Hughes. One reason: "Magnesium is hard to study because blood levels don't reflect tissue levels."

Nevertheless, some studies find greater bone density in people who consume more magnesium. "The best way to get magnesium is from whole grains, nuts, and vegetables," says Tucker. "But both potassium and magnesium are easily lost in processing, so they're low in the U.S. diet."

* Soft drinks. An Irish study found lower bone density in teenage girls who drink more soft drinks. (13) Another found more fractures in girls who drink more cola, but not other sodas. (14)

"Some researchers think the negative effect on bone is due to soft drinks' displacing milk," says Tucker. "But others think that only colas cause calcium loss because they have phosphoric acid, which can interfere with calcium absorption."

* Soy. Soybeans are rich in plant estrogens called isoflavones. Can they replace the bone-boosting estrogens that women lose when they go through menopause? It's too early to say.

In a study of 175 women aged 60 to 75, isoflavone-rich soy protein had no impact on bone density (of memory or LDL cholesterol) after one year. (15)

But two longer studies are still under way. One is testing soy isoflavones (not soy protein) on 400 postmenopausal women for two years. The second is giving isoflavones to 234 women for three years.

* Sodium. Like caffeine, sodium also increases calcium excretion. According to the National Academy of Sciences, every 500 mg of sodium (from salt) causes postmenopausal women to lose an extra 10 mg of calcium. As with caffeine, taking more calcium can offset the loss.

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

(1) New Eng. J. Med. 327: 1637, 1992.

(2) New Eng. J. Med. 337: 670, 1997.

(3) J. Amer. Med. Assoc. 291: 1999, 2004.

(4) Endocrinol. Rev. 23: 560, 2002.

(5) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 89: 5387, 2004.

(6) Amer. J. Clin. Nutr. 71: 1201, 2000.

(7) Calcif. Tissue Int. 73: 21, 2003.

(8) Amer. J. Clin. Nutr. 75: 773, 2002.

(9) Amer. J. Clin. Nutr. 69: 727, 1999.

(10) J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90: 831, 2005.

(11) J. Amer. Med. Assoc. 287: 47, 2002.

(12) J. Amer. Med. Assoc. 288: 2300, 2002.

(13) J. Bone Mineral Res. 18: 1563, 2003.

(14) Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 154: 610, 2000.

(15) J. Amer. Med. Assoc. 292: 65, 2004.

Super Remodel

Most of the adult skeleton is replaced about every 10 years. Remodeling repairs small cracks, gets rid of old bone, and frees up calcium in case the body needs it.

1. Bone-dissolving cells called osteoclasts approach old bone.

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

2. Osteoclasts use enzymes to dissolve bone tissue.

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

3. Bone-building cells called osteoblasts prepare to lay down a bone matrix made mostly of a protein called osteocalcin.

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

4. Calcium and phosphorus attach to the matrix and create new bone.

[ILLUSTRATION OMITTED]

COPYRIGHT 2005 Center for Science in the Public Interest

COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale Group