505(b)(2) APPLICATIONS: HISTORY, SCIENCE, AND EXPERIENCE*

In 1984, the 505(b)(2) application route for a New Drug Application was created by Congress to allow applicants to create innovative medicines using currently available products without performing a full complement of safety and efficacy studies. This article reviews the history of the approach, provides examples, and considers some of the scientific and technical challenges associated with documenting safety and efficacy relative to the proposed change. The approach does not appear to have been used extensively in the almost 18 years since it was created. The explanation for this is not fully apparent, but may relate to the limited exclusivity, usually three years, allowed for a 505(b)(2) application.

Key Words: Waxman-Hatch; 505(b)(2); Pharmaceutical equivalence; Bioequivalence; Listed drug; Patent certification

INTRODUCTION

PASSAGE OF THE Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 (Waxman-Hatch) created Section 505(b)(1) and (b)(2) of the Federal Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act. Previously, the act only described a 505(b) application. The language of this section states (1):

A 505(b)(2) application is one that is submitted under paragraph (1) for a drug for which the investigations described in clause (A) of such paragraph and relied upon by the applicant for approval of the application were not conducted by or for the applicant and for which the applicant has not obtained a right of reference or use from the person by or for whom the investigations were conducted ....

505(b)(2) New Drug Applications (NDAs) provide opportunities for pharmaceutical sponsors to create new drug products based on the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA's) primary finding of safety and efficacy of a predicate product (the listed drug). In addition to this finding, FDA may require additional information from preclinical or clinical trials and/or information from the literature needed to support the change of the new drug product. FDA may also allow approval of 505(b)(2) applications without a listed drug.

The purpose of this article is to review experience with 505(b)(2) applications, relying on publicly available information from the agency or applicants. This article considers briefly the regulatory history of these applications, then discusses scientific and technical issues associated with these types of applications. Legal aspects of 505(b)(2) applications have been considered in detail elsewhere (2) and are also discussed in a draft FDA guidance (3). FDA has not issued the final version of this guidance and is now apparently considering public response to it. This public response has included a comment and a citizen petition (4,5). Arguments in these documents focus on either the regulatory or constitutional impediments to the general approach ('taking' arguments) and the use of an `Orange Book' equivalence rating where the intent of the 505(b)(2) application is to show equivalence.

REGULATORY HISTORY

The history of Section 505(b)(2) begins with societal control, as expressed through laws passed by Congress, for the development, manufacture, and marketing of medications in the United States. To come to the present system of drug regulation, this control at times has had to carefully consider when drug products are the same or different. In brief:

* 1903 federal law required that biologic products such as vaccines be evaluated for 'safety, purity, and potency,'

* The 1906 Food and Drugs Act added regulation of drugs other than biologics,

* The 1938 Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act created the FDA and required that the new agency conduct a safety evaluation on drugs prior to marketing based on data submitted in an NDA,

* The drug amendments of 1962 amended the act to include an effectiveness requirement for approval of an NDA,

* FDA created the Drug Efficacy Study Implementation (DESI) project to assess the efficacy of new drugs approved between 1938 and 1962,

* Pending conclusion of a DESI finding, FDA permitted marketing of 'old' 'me-too' drug products (as opposed to pre- 1938 grandfathered products) that were identical, similar, or related to drug products that were undergoing DESI review and that had entered the market between 1938 and 1962, Via a 1970 Federal Register notice published April 24, 1970 (35 FR 6574), FDA terminated marketing of 'me-too' drug products unless the DESI review had confirmed the safety and efficacy of a corresponding reference product and the manufacturer of the 'me-too' product submitted an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) that provided information about its formulation and manufacture,

* The Supreme Court in the United States v. Generix Drug Corporation concluded that each 'me-too' drug product marketed between 1938 and 1962 required an ANDA,

* FDA finalized the 1977 Bioavailability/ Bioequivalence regulations (21 CFR 320) that supported a requirement for bioavailability in NDAs, including DESI-effective new drugs approved between 1938 and 1962, and bioequivalence data in ANDAs as part of the safety and efficacy information in an application,

* FDA created the paper NDA policy in 1981 (46 FR 27396, May 19, 1981) to permit approval of generic equivalents of post1962 new drug products based on literature- and product-specific data,

* Congress passed the 1984 Waxman-Hatch amendments to the act that created a generic new drug approval system (505(j)) for all new drugs and that terminated the need for a paper NDA policy,

* Section 505(b)(2) in the 1984 amendments extended the paper NDA policy beyond duplicates to any NDA containing studies not conducted by or for the applicant and to which the applicant has not obtained a right of reference,

* A 1987 FDA letter (Parkman letter) to all NDA and ANDA applicants provided recommendations on the types of changes that might be suitable under Section 505(b)(2), and

* An FDA draft guidance published for comment in October 1999 elaborated on statutory and regulatory definitions of 505(b)(2) applications, provided examples, indicated what was not suitable for a 505(b)(2) application, further considered general and patent/exclusivity implications for 505(b)(2) applications, and described what should be included in such applications.

EXAMPLES

The following examples of applications submitted pursuant to 505(b)(2) are based on publicly available information from the FDA. In certain instances, as noted, confirmation was not possible. The specific examples are presented in the categories listed in the draft FDA guidance. The examples do not represent a complete list of 505(b)(2) applications:

*Change in dosage form/dosing regimen: Naproxen Sodium Extended Release Tablets (NDA 20-353) and Betamethasone Valerate Aerosol (NDA 20-934),

* Change in strength: Ethinyl Estradiol/Levonorgestrel Tablets 0.05 mg/0.25 mg (NDA 20-946), and Hydrochlorothiazide Capsules 12.5 mg (NDA 20-504),

* Change in route of administration: Menotropins Injection Subcutaneous Route (NDA 21-047),

Substitution of an active ingredient in a combination product: Ibuprofen/Pseudoephedrine HCL Tablets 200 mg/30 mg (NDA 19-771/not confirmed),

* New active ingredient: Timolol Ophthalmic Solution (NDA 20-439/not confirmed), and Trimethoprim HCL Solution (NDA 74374),

* Enantiomer from a racemate: Levalbuterol HCL Inhalation Solution (NDA 20-837),

* Metabolite: No known example,

* New molecular entity: Talc Metered Aerosol (NDA 20-587),

* New formulation: Tretinoin Cream 0.025% (NDA 20-400),

* New combination drug product: No known example, and

* Prescription to over-the-counter switch: Miconazole Nitrate Vaginal Cream (NDA 17-450/not confirmed).

Readers are encouraged to correct these examples in terms of their status, given that FDA did not begin placing approval letters, which indicate the route of approval, on its Internet site until 1998. The authors would also welcome additional examples.

DISCUSSION

Congressional and FDA actions have created a system whereby all new drugs approved after 1938 may be subject to generic substitution following expiration of patent and exclusivity. An applicant submitting a 505(j) application (ANDA) must provide data to show that the drug product is pharmaceutically equivalent and bioequivalent to the reference listed drug. In addition, an applicant submitting an ANDA must file a patent certification to indicate noninfringement and must not market the product before patent and/or exclusivity attached to the listed drug has expired. A sponsor of a 505(b)(2) application for a change to a listed drug product must also file a patent certification and exclusivity statement and may not market the approved product until patent/exclusivity attached to that drug product has expired or the patent has been successfully challenged.

An applicant submitting an NDA pursuant to Section 505(b)(2) relies on FDA's finding of safety and effectiveness for all elements of the application except those related to the proposed change. The presumption of a 505(b)(2) application is that the nonchange information in a 505(b)(2) application stands in relation to the safety and efficacy data in an NDA in the same way as does the information in an ANDA application. A 505(b)(2) applicant does not need to show pharmaceutical equivalence, for example, different salts of the same active moiety and/or different combinations may be studied. Also, whereas an ANDA application must contain information to document bioequivalence, a 505(b)(2) applicant may be required to conduct a bioavailability study, which may or may not be comparative, depending on discussions with the agency.

The challenge of a 505(b)(2) application, both for FDA and the applicant, is to determine what additional information is needed to support the proposed change. As noted at 21 CFR 314.54, the 'application need contain only that information needed to support the modifications) of the listed drug.' This will usually be a case-by-case determination. In some instances, where the primary change is reflected adequately in the systemic concentration-time profile (for example, development of a modified release product based on data developed for an immediate release product), the amount of information may be satisfied through a comparative bioavailability study (4). In other instances, substantial additional safety, efficacy, and other information may be needed to support a modification. Using the immediate release to modified release modification as an example, if the modified release dosage form produces concentration fluctuations that are substantially greater than those observed with the immediate release dosage form, additional safety/ efficacy studies may be needed, particularly for drugs with significant adverse effects or steep dose/response curves. A further example of this might be when an applicant is required to perform nonclinical pharmacology toxicology studies in accordance with International Conference on Harmonization and other agency guidances that were not in effect at the time of the original approval.

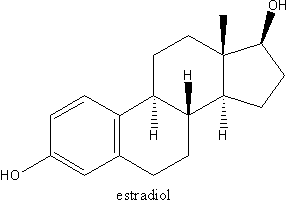

FDA guidances (6) and discussions with the involved FDA review division should be helpful in understanding the data needed to bridge between a finding of safety and efficacy for a listed drug product and a finding of safety and efficacy for a proposed changed drug product. For a prescription to over-thecounter switch, little or no clinical information may be required if the strength and dosage form of the proposed over-the-counter product do not change. In this instance, data may only be needed to show that patients may safely self-diagnose and medicate the product according to proposed labeling. In other instances, the amount of nonclinical and clinical information to allow bridging may be more extensive. This would perhaps be the case where a subset of a mixture is planned for submission, for example, Conjugated Estrogens Synthetic A and an enantiomer from a racemate (7). In these instances, additional information may be needed to differentiate between the safety and efficacy of the listed drug mixture and the proposed subset.

An interesting feature of the 505(b)(2) approach relates to applications where the information needed is considered beyond limited confirmatory testing (See Federal Register notice of April 28, 1992 (57 FR 17958)), and yet the application is for a pharmaceuticallyequivalent and bioequivalent drug product. While usually the application for this type of drug product should be submitted as a 505(j) application, the 505(b)(2) approach allows the requisite information to include information beyond limited confirmatory testing to be considered by appropriate FDA staff.

The general concept was proposed in the October 1999 draft FDA guidance. While most 505(b)(2) applications will yield noninterchangeable drug products, a drug product submitted according to this approach may still be deemed to be interchangeable and receive an appropriate `Orange Book' or equivalent rating to a listed drug. Hypothetical examples of products that might be both pharmaceutically equivalent and bioequivalent but may still be suitable for submission as a 505(b)(2) application include:

1. An interchangeable product containing a complex active ingredient, and

2. A product in which a new excipient is qualified by safety studies that are considered beyond limited confirmatory testing. Should regulatory experience someday conclude that the information needed is not beyond limited confirmatory testing, the same application could be filed pursuant to 505(j).

The 505(b)(2) approach appears to satisfy a public health objective not to request clinical studies to document what is already known about a drug or drug product. The general principle was first enunciated in the Parkman letter (April 10, 1987), which states that the 505(b)(2) route to approval promotes innovation and discourages unnecessary, wasteful, and duplicative studies. While the general approach appears reasonable, it has been opposed (3,4) on the grounds that it goes beyond Congressional intent. Further discussion and debate will be needed before the matter is finally resolved.

SUMMARY

The current 505(b)(2) application was intended to encourage development of innovative medicines without conducting unnecessary safety and efficacy studies. While the examples cited do not represent all examples, it appears that the approach has not been used extensively in the 17 years since its creation. The reason for this may perhaps relate to low market potential for new drug products that represent a change from a listed drug product. In addition, exclusivity for most products approved pursuant to a 505(b)(2) application would be only three years, thus limiting the incentive to use this approach. In general, FDA and applicants are still gaining experience with the general approach, and further modifications may be needed.

*The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not represent the views of either Lachman Consulting or the United States Pharmacopeia.

REFERENCES

1. 21 U.S.C. 355(b)(2).

2. Sasinowski FJ, Scarlett T. Reliance on phantom ANDAs to access NDA data. Reg Affairs. 1991;3: 467-482.

3. US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Guidance: Applications Covered by Section 505(b)(2). Rockville, MD: US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research: October 1999. http:/www.fda. gov/cder/guidanc&2853dft.htm.

4. FDA Public Docket No. 99D-4809, Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, April 3, 2000.

5. Morgan, Lewis & Bockius Citizen Petition, FDA's Docket Management Branch, July 27, 2001.

6. US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug and Biologics Evaluation and Research. Guidance: Providing Evidence of Effectiveness for Human Drug and Biologic Products. Rockville, MD: US Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug and Biologics Evaluation and Research. May 1998. http://www.fda. gov/cder/guidance/1397fnl.pdf.

7. US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance: FDA's Policy Statement for the Development of New Stereoisomeric Drugs. Rockville, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; May 1992. http://www.fda.gov/cder/ guidance/stereo.htm.

GORDON JOHNSTON, MS, RPH

Lachman Consultant Services, Westbury, New York

ROGER L. WILLIAMS, MD

United States Pharmacopeia, Rockville, Maryland

Reprint address: Roger L. Williams, MD, U.S. Pharmacopeia, 12601 Twinbrook Parkway, Rockville MD 20852-1790.

Copyright Drug Information Association Apr-Jun 2002

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved