Based on an industry-sponsored symposium presented at the American Society for Reproductive Medicine 2003 Annual Meeting, October 14, 2003, in San Antonio, Texas

The full text of this CME supplement is available at OBG MANAGEMENT'S website: www.obgmanagement.com

With the early termination of the WHI, clinicians find it difficult--if not impossible--to determine how best to apply the results to patients who want relief from menopausal symptoms that often interfere with daily functioning and reduce quality of life.

New Options in Hormone Therapy: Safety, Efficacy, and What Your Patients Need to Know, a CME supplement to the July 2004 issue of OBG MANAGEMENT, provides valuable information for gynecologists and family practice physicians who provide healthcare for this population. The publication is available in PDF form at www.obgmanagernent.com. Key points are reviewed below.

In assessing the appropriateness of hormone therapy (HT) for the individual patient, clinicians should:

Determine cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. An early menopausal patient with slightly elevated lipid levels and no other CVD risk factors may have a 1% chance of a coronary event during the next decade. HT is unlikely to increase this patient's CVD risk.

Consider age. Cumulative data and findings of the WHI itself strongly support the argument that HT does not pose a significant CHD risk in women who are less than 10 years postmenopausal. As time since menopause increases, so does risk for atherosclerosis and coronary events. Patient age is a critical factor in risk for thrombotic (as opposed to hemorrhagic) stroke.

Select dosage and route of administration. National organizations have issued guidelines that emphasize the following points:

* HT should be used at the lowest effective dose for symptom relief over the shortest period of time. (2, 3)

* Nonoral routes of administration may offer advantages, although the long-term benefit/risk is unknown. (3)

Assess the whole patient. Look at the patient's total benefit/risk profile. HT is associated with significant risk reduction for colorectal cancer and osteoporosis. For women at high risk for these conditions, HT may provide significant benefits.

How long should patients take HT? Vasomotor symptoms generally subside within a few years. Vaginal atrophy worsens; long-term, topically applied agents may be sufficient.

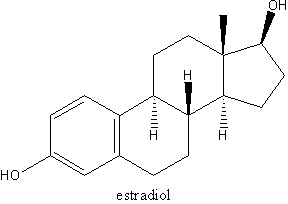

AGENTS AND REGIMENS Oral HT. Metabolized primarily in the liver, oral HT agents are associated with increases in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, decreases in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and increases in triglycerides. (4-7) In the liver, 80% to 90% of estradiol (E2), the most abundant estrogen in premenopausal women, is converted to less biologically active forms. (8)

The WHI's increased incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) may be related to first-pass hepatic metabolism and effects on the coagulation cascade. (9-10) C-reactive protein, elevated in users of oral HT (via first-pass hepatic metabolism), may have a proinflammatory effect. (11)

Low-dose oral HT has a slower onset of symptom relief, but the risk of adverse events may be decreased. Serum levels fluctuate.

Nonoral HT. These agents bypass first-pass hepatic metabolism and maintain a 1:1 ratio of E2 to estrone. (12) Symptom relief is rapid; steady systemic levels are maintained. (13)

Transdermal patches provide rapid symptom relief. Generally, peak concentrations are attained in 2 to 8 hours, after which levels tend to decrease. (14) Absorption may be influenced by patch location. (15) Low levels have been reported in some patch users, possibly related to individual differences in skin and hair follicle characteristics. (16) Patch-related skin irritations or adhesion problems have been reported in 20% to 40% of users. (17)

Percutaneous gels contain 17[beta]-estradiol. Dispensed from a dose pump, the hydroalcoholic gel is applied and absorbed quickly without residue. Significant symptom relief is rapid. Steady systemic E2 levels are maintained. Skin irritation is minimal. (18)

Vaginal rings deliver 3-month supplies of HT and maintain stable serum levels. Circulating plasma E2 levels are generally in the postmenopausal range but sufficient to maintain normal mucosa and prevent vaginal atrophy. The ting may be expelled and may cause irritation. (19-21)

THE WOMEN'S HEALTH INITIATIVE: AN OVERVIEW

* The hormone therapy (HT) arm of the Women's Health Initiative (WHI) was designed to answer 1 basic question: As had been suggested in observational trials, does HT reduce the incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD) in postmenopausal women? The primary efficacy outcome for the WHI estrogen plus progestin arm was reduction of CHD (defined as nonfatal myocardial infarction or death from CHD). The primary adverse outcome was incidence of invasive breast cancer.

* Recently symptomatic menopausal women were excluded. Participants were older than those who use HT for menopausal symptoms. They were at significantly higher risk for CHD.

* The WHI assessed the risks and benefits of only 1 oral estrogen/progestin regimen in use for many years.

* Current investigations are focused on determining the lowest dose of estrogen for effective relief of menopausal symptoms and the lowest dose of progestogen to adequately protect the endometrium.

* Nonoral routes of administration of estrogen or estrogen/progestin also have been developed.

REFERENCES

(1.) Writing Group for the WHI Investigators. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results from the women's health initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:321-333.

(2.) North American Menopause Society. Clinical Recommendations for Postmenopausal Hormone Therapy. Available at: www.menopause.org/aboutmeno/Htposition statement.pdf. Accessed September 19, 2003.

(3.) American Society for Reproductive Medicine position statement. Available at: www.asrm.org/Media/misc_announcements/whi2.html. Accessed February 17, 2004.

(4.) The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial. Effects of estrogen or estrogen/progestin regimens on heart disease risk factors in postmenopausal women. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial. JAMA. 1995;273:199-208.

(5.) Tikkanen MJ, Nikkila EA, Kuusi T, et al. High density lipoprotein-2 and hepatic lipase: reciprocal changes produced by estrogen and norgestrel. J Clin Endocnnol Metab. 1982;54:1113-1117.

(6.) Basdevant A, de Lignieres B, Simon P, et al. Hepatic lipase activity during oral and parenteral 17 beta-estradiol replacement therapy: high-density lipoprotein increase may not be antiatherogenic. Fertil Steril. 1991;55:1112-1117.

(7.) Pang SC, Greendale GA, Cedars MI, et al. Long-term effects of transdermal estradiol with and without medroxyprogesteroneacetate. Fertil Steril. 1993;59:76-82.

(8.) Kuhl H. Pharmacokinetics of oestrogens and progestogens. Maturitas. 1990;12:171-197.

(9.) Vengpatanasin W, Tuncel M, Wang Z, et al. Differential effects of oral versus transdermal estrogen replacement therapy on C-reactive protein in postmenopausal women. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1358-1363.

(10.) Cushman M, Legault C, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Effect of postmenopausal hormones on inflammation-sensitive proteins: the Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Study. Circulation. 1999;100:717-722.

(11.) Decensi A, Omodel U, Robertson C, et al. Effect of trans dermal estradiol and oral conjugated estrogen on Creactive protein in retinoid-placebo trial in healthy women. Circulation. 2002;106:1224-1228.

(12.) Dupont A, Dupont P, Cusan L, et al. Comparative endocrinological and clinical effects of percutaneous estradiol and oral conjugated estrogens as replacement therapy in menopausal women. Maturitas. 1991;13:297-311.

(13.) Notelovitz M. Urogenital aging: solutions in clinical practice. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;59 (suppl 1):$35-$39.

(14.) Kuhl H. Pharmacokinetics of oestrogens and progestogens. Maturitas. 1990;12:171-197.

(15.) Notelovitz M. Clinical experience with a 7-day estrogen patch: principles and practice. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1998;12:248-258.

(16.) Reginster JY, Albert A, Deroisy R, et al. Plasma estradiol concentrations and pharmacokinetics following transdermal application of Menorest 50 or System (Evorel) 50. Maturitas. 1997;27:179-186.

(17.) Archer DF, Furst K, Tipping, et al for the Combipatch Study Group. A randomized comparison of continuous combIned transdermal delivery of estradiol-norethindrone acetate and estradiol alone for menopause. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:498-503.

(18.) Archer DF for the EstroGel Study Group. Percutaneous 17-B estradiol gel for the treatment of vasomotor symptoms in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2003;6:516-521.

(19.) Al-Azzawi F, Buckler HM; United Kingdom Vaginal Ring Investigator Group. Comparison of a novel vaginal ring delivering estradiol acetate versus oral estradiol for relief of vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Climacteric. 2003;6:118-127.

(20.) Buckler H, Al-Azzawi F; UK VR Multicentre Trial Group. The effect of a novel vaginal ring delivering oestradiol acetate on climacteric symptoms in postmenopausal women. BJOG. 2003;110:753-759.

(21.) Speroff L. Efficacy and tolerability of a novel estradiol vaginal ring for relief of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:823-834.

David F. Archer, MD

Chair, Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Director, CONRAD Clinical Research Center

Eastern Virginia Medical School

Norfolk, VA

James A. Simon, MD

Clinical Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology

George Washington University School of Medicine

Washington, DC

Vivian Lewis, MD

Strong Fertility & Reproductive Science Center

University of Rochester Medical Center

Rochester, NY

COPYRIGHT 2004 Dowden Health Media, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group