(Chest 1992; 102:239-50) ACE = angiotension-converting enzyme; BAL = broncho-alveolar lavage; BCNU = carmustine; BOOP = bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia; IL-2 = interleukin-2; PVOD = pulmonary veno-occlusive disease

Diagnosing drug-induced pulmonary disease remains a challenge for all pulmonologists. Keeping up with what is new in this field is also a challenge. This review is intended for the pulmonologist who has a good working knowledge of the effects of drugs on the lungs but who needs to be brought up-to-date. One of us (E. C. R.) collects monthly Med-Line searches of articles pertaining to drug-induced pulmonary disease. Interestingly, the majority of the articles referred to in this review are from journals other than the one that pulmonologists would be expected to read. There are a number of reviews of this subject for those interested in more in-depth information.[1-5] Drugs known to cause pulmonary disease are shown in Table 1. Not all the drugs known to induce pulmonary disease will be discussed in this review unless new information has become available in the past several years.

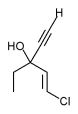

Alveolar proteinosis has been recognized in a number of patients receiving chemotherapy, primarily busulfan (Fig 4).[87-89] For the most part, these patients have chronic myelogenous leukemia. The histology of the alveolar proteinosis is identical to that seen in the spontaneous primary form, but anecdotal experience suggests that patients are less likely to respond to therapeutic lavage. Of over 200 patients with alveolar proteinosis, reviewed by Bedrossian et al,[87] nearly 15 percent had a hematologic disorder, and may were receiving chemotherapeutic agents. It has been suggested that epithelial hyperplasia caused by the drugs, particularly busulfan, is probably responsible for the induction of excessive surfactant production.

Pneumothorax has been reported following therapy with a number of chemotherapeutic agents,[90-92] but it appears that bleomycin is the one most commonly mentioned.[91-92] In one report, 30 percent of the patients receiving BCNU eventually developed pneumothorax. In one series, all four patients receiving amiodarone who developed ARDS also had pneumothoraces.[23]

Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease (PVOD) has been associated with the use of bleomycin, mitomycin-C, BCNU, etoposide, and cyclophosphamide.[93-95] There are scattered reports of this condition occurring following bone marrow transplantation. It has been noted that a high dose of methylprednisolone brought about clinical remission. The roentgenographic changes may mimic drug-induced pulmonary disease as well as many other complications. However, hemosiderinladen macrophages in BAL specimens may provide a clue to the diagnosis. In addition, the presence of Kerley B lines on the chest roentgenogram raises the suspicion of PVOD.

Classification by End-Organ Response

Bronchiolitis Obliterans with Organizing Pneumonia

Bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia has been described as a manifestation of drug toxicity for a number of medications (Table 3).[5,48,49,67,96] Patients frequently have isolated or patchy air space opacities, which can mimic pulmonary infections or neoplasms. The morphologic changes are usually indistinguishable from those described in so-called idiopathic BOOP. Most patients recover with corticosteroid therapy.

Bronchospasm

Bronchospasm as a complication of drug-induced pulmonary disease should be considered in any asthmatic patient receiving any medication.[97,98] Table 4 lists the drugs known to cause or aggravate bronchospasm. Vinblastine is a drug that has been around for many years, but only in the last several years has it been combined with mitomycin. The two appear to act synergistically to produce bronchospasm.[59,60] A small but definite percentage of patients who have an acute nitrofurantoin reaction will have bronchospasm with or without parenchymal changes.

Acetylsalicylic acid is said to produce a worsening of bronchospasm in at least 5 percent of asthmatic patients and should always be considered a potential aggravator.[99,100] There are over 200 proprietary drugs containing acetylsalicylic acid, and patients may not mention these as drugs taken. The nonacetylated salicylates have been shown to be safe in asthmatic patients,[99] whereas nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents may cause bronchospasm.[101]

As noted earlier, IL-2 may aggravate bronchospasm and should be used with caution in any patient with a known history of obstructive lung disease.[54] Dipyridamole increases the concentration of adenosine, which is a bronchoconstrictive agent, and a very small percentage (less than 1 percent) of patients receiving this medication at the time of a thallium study will develop significant bronchospasm.[102] Almost all of these patients have underlying obstructive lung disease and should be protected with theophylline prior to the use of dipyridamole and certainly should be given theophylline should bronchospasm occur at the time of using this drug.

Protamine has some unusual side effects that usually occur during general anesthesia when the drug is used to reverse anticoagulant effects of coronary bypass. One of these effects is significant bronchospasm, which should be kept in mind by the anesthesiologist.[103]

Nebulizing any medication, such as pentamidine or beclomethasone, or propellant has the potential of aggravating irritable airways.[104-106] Beclomethasone is the only nebulized corticosteroid recognized to aggravate bronchospasm. There are two conflicting reports on the protective benefits of albuterol in pentamidine-induced bronchoconstriction. Quieffin et al[107] demonstrated that 34 percent of subjects had a decrease in [FEV.sub.1] of 10 percent or more, but it was effectively prevented by albuterol or ipratropium, whereas cromolyn sodium was only partially effective. They were unable to demonstrate any predictive factors. Katzman et al[108] found that 26 percent of patients developed a reduction in [FEV.sub.1] of 15 percent or more in their patients, but albuterol did not protect against this event.

Paradoxical bronchospasm in response to nebulized beta-agonists occurs rarely.[109 Intravenous hydrocortisone has been reported to cause severe asthma and is the only corticosteroid that has been recognized to do this.[98] Methotrexate has recently been implicated as a causative agent in inducing asthma.[110,111]

Cocaine has many adverse effects on the body, as well as the lung specifically, and one of them is bronchospasm.[66-69] Propafenone is a new antiarrhythmic agent with scattered reports of aggravating asthma; this should be avoided in patients at risk.[112,113]

Pleural Effusion

Table 5 lists the drugs that have been associated with pleural effusion.[114-116] The mechanism is unknown. Studies of the pleural fluid ar few and far between, such that the analysis of pleural fluid in the presence of these drugs gives little insight into the diagnostic accuracy and really serves as a source of eliminating other possible causes. A recent report of a procainamide-induced lupus pleuritis disclosed a white blood cell count of 53,200/cu mm (70 percent polymorphonuclear leukocytes), a pH of 7.195, and a lactate dehydrogenase value of 4,296 IU/L, suggesting a pleural space infection (glucose, 79 mg/dl), that cleared with discontinuation of the drug.[117]

Interestingly, with bromocriptine there is an intense lymphocytic response that is quite characteristic in this setting. Whether this is associated with other listed drugs is unknown.

Pulmonary Insufficiency

Table 6 lists the drugs associated with acute onset of pulmonary insufficiency, whether due to noncardiac pulmonary edema or an acute inflammatory reaction.[118,119] Reed and Glauser[118] reviewed the literature and summarized the drugs that are known to do this as well as suspected theories.

Table 7 lists the drugs that cause subacute respiratory insufficiency. L-Tryptophan is not discussed because it is no longer available.

Figure 5 lists known or suspected drug synergisms, most of which have been discussed already.

Table 8 outlines the results of BAL in drug-induced pulmonary disease.[120-122] Unfortunately, in most situations the results are nondiagnostic, but they are frequently useful in excluding other causes (eg, infection). [Tabular Data 8 Omitted]

References

[1]Cooper JAD Jr, White DA, Matthay RA. During-induced pulmonary disease: part 1. cytotoxic drugs. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986; 133:321-40 [2]Cooper JAD Jr, White DA, Matthay RA. Drug-induced pulmonary disease: part 2. noncytotoxic drugs. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986; 133:488-505 [3]Rosenow EC III. Drug-induced pulmonary disease. In: Murray JF, Nadel JA, eds. The textbook of respiratory medicine. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1988; 1681:702 [4]Akoun GM, White JP. Treatment-induced respiratory disorders. In: Dukes MNG, ed. Drug-induced disorders. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1989 [5]Myers JL. Pathology of drug-induced lung disease. In: Katzenstein AL, Askin F, eds. Surgical pathology of non-neoplastic lung disease. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1990 [6]Sebastian JL, McKinney WP, Kaufman J, Young MJ. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and cough: prevalence in an outpatient medical clinic population. Chest 1991; 99:36-9 [7]Gibson GR. Enalapril-induced cough. Arch Intern Med 1989; 149:2701-03 [8]Lindgren BR, Rosenquist U, Ekstrom T, Gronneberg R, Karlberg BE, Andersson RGG. Increased bronchial reactivity and potential skin responses in hypertensive subjects suffering from coughs during ACE-inhibitor therapy. Chest 1989; 95:1225-30 [9]Bucca C, Rolla G. Pinna G, Oliva A, Bugiani M. Hyperresponsiveness of the extrathoracic airway in patients with captopril-induced cough. Chest 1990; 98:1133-37 [10]Kaufman J, Cassanova JE, Riendl P, Schlueter DP. Bronchial hyperreactivity and cough due to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors. Chest 1989; 95:544-58 [11]Boulet LP, Milot J, Lampron N, Lacourciere Y. Pulmonary function and airway responsiveness during long-term therapy with captopril. JAMA 1989; 261:413-16 [12]Aldis WL. Cromolyn for cough due to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy: preliminary observations [letter]. Chest 1991; 100:1741-42 [13]Kidney JC, O'Halloran DJ, Fitzgerald MX. Captopril and lymphocytic alveolitis. BMJ 1989; 299:981 [14]Martin WJ II, Rosenow EC III. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity: recognition and pathogenesis--part I. Chest 1988; 93:1067-75 [15]Martin WJ II, Rosenow EC III. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity: recognition and pathogenesis--part II. Chest 1988; 93:1242-48 [16]Kuhlman JE, Teigen C, Ren H, Hruban RH, Hutchins GM, Fishman EK. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity: CT findings in symptomatic patients. Radiology 1990; 177:121-25 [17]Ren H, Kuhlman JE, Kruban RH, Fishman EK, Wheeler PS, Hutchins GM. CT-pathology correlation of amiodarone lung. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1990; 14:760-765 [18]Nicholson AA, Hayward C. The value of computed tomography in the diagnosis of amiodarone-induced pulmonary toxicity. Clin Radiol 1989; 40:564-67 [19]Piccione W Jr, Faber LP, Rosenberg MS. Amiodarone-induced pulmonary mass. Ann Thorac Surg 1989; 47:918-19 [20]Arnon R, Raz I, Chajek -Shaul T, Berkman N, Fields S, Bar-On H. Amiodarone pulmonary toxicity presenting as a solitary lung mass. Chest 1988; 93:425-27 [21]Kay GN, Epstein AE, Kirklin JK, Diethelm AG, Graybar G, Plumb VJ. Fatal postoperative amiodarone pulmonary toxicity. Am J Cardiol 1988; 62:490-92 [22]Nalos PC, Kass RM, Gang ES, Fishbein MC, Mandel WJ, Peter T. Life-threatening postoperative pulmonary complications in patients with previous amiodarone pulmonary toxicity undergoing cardiothoracic operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1987; 93:904-12 [23]Tuzcu EM, Maloney JD, Sangani BH, Masterson ML, Hocevar KD, Golding LAR et al. Cardiopulmonary effects of chronic amiodarone therapy in the early postoperative course of cardiac surgery patients. Cleve Clin J Med 1987; 54:491-95 [24]Greenspon AJ, Kidwell GA, Hurley W, Mannion J. Amiodarone-related postoperative adult respiratory distress syndrome. Circulation 1991; 84:407-15 [25]Camus P, Lombard JN, Perrichon M, Piard F, Gu erin JC, Thivolet FB, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia in patients taking acebutolol or amiodarone. Thorax 1989; 44:711-15 [26]Dunn TL, Gerber MJ, Shen AS, Fernandez E, Iseman MD, Cherniack RM. The effect of topical ophthalmic instillation of timolol and betaxolol on lung function in asthmatic subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis 1986; 133:264-68 [27]Weinreb RN, van Buskirk EM, Cherniack R, Drake MM. Long-term betaxolol therapy in glaucoma patients with pulmonary disease. Am J Ophthalmol 1988; 106:162-67 [28]Brooks AM, Burden JG, Gillies WE. The significance of reactions to betaxolol reported by patients. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1989; 17:353-55 [29]Feinberg L, Travis WD, Ferrans V, Sato N, Bernton HF. Pulmonary fibrosis associated with tocainide: report of a case with literature review. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990; 141:505-08 [30]Kohno S, Yamaguchi K, Yasuoka A, Koga H, Hayashi T, Komori K, et al. Clinical evaluation of 12 cases of antimicrobial drug-induced pneumonitis. Jpn J Med 1990; 29:248-54 [31]Dutcher JP, Kendall J, Norris D, Schiffer C, Aisner J, Wiernik PH. Granulocyte transfusion therapy and amphotericin B: adverse reactions? Am J Hematol 1989; 31:102-08 [32]Levine SJ, Walsh TJ, Martinez A, Eichacker PQ, Lopez-Berestein G, Natanson C. Cardiopulmonary toxicity after liposomal amphotericin B infusion. Ann Intern Med 1991; 114:664-66 [33]Evans RB, Ettensohn DB, Fawaz-Estrup F, Lally EV, Kaplan SR. Gold lung: recent developments in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1987; 16:196-205 [34]Carson CW, Cannon GW, Egger MJ, Ward JR, Clegg DO. Pulmonary disease during the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with low dose pulse methotrexate. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1987; 16:186-95 [35]McKendry RJR, Cyr M. Toxicity of methotrexate compared with azathioprine in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: a case-control study of 131 patients. Arch Intern Med 1989; 149:685-89 [36]Newman ED, Harrington TM. Fatal methotrexate pneumonitis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988; 31:1585-86 [37]Elsasser S, Dalquen P, Soler M, Perruchoud AP. Methotrexate-induced pneumonitis: appearance four weeks after discontinuation of treatment. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989; 140:1089-92 [38]Wollner A, Mohle Boetani J, Lambert RE, Perruquet JL, Raffin TA, McGuire JL. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia complicating low dose methotrexate treatment for rheumatoid arthritis. Thorax 1991; 46:205-07 [39]Leatherman JW, Schmitz PG. Fever, hyperdynamic shock, and multiple-system organ failure: a pseudo-sepsis syndrome associated with chronic salicylate intoxication. Chest 1991; 100:1391-96 [40]O'Driscoll BR, Hasleton PS, Taylor PM, Poulter LW, Gattamaneni HR, Woodcock AA. Active lung fibrosis up to 17 years after chemotherapy with carmustine (BCNU) in childhood. N Engl J Med 1990; 323:378-82 [41]Jules-Elysee K, White DA. Bleomycin-induced pulmonary toxicity. Clin Chest Med 1990; 11:1-20 [42]Van Barneveld PWC, Sleijfer DT, VanDerMark TW, Mulder NH, Schraffordt Koops H, Sluiter HJ, et al. Natural course of bleomycin-induced pneumonitis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987; 135:48-51 [43]Wolkowicz J, Sturgeon J, Rawji M, Chan CK. Bleomycin-induced pulmonary function abnormalities. Chest 1992; 101:97-101 [44]Goldiner PL, Carlon GC, Cvitkovic E, Schweizer O, Howland WS. Factors influencing postoperative morbidity and mortality in patients treated with bleomycin. BMJ 1978; 1:1664-67 [45]Waid-Jones MI, Coursin DB. Perioperative consideration for patients treated bleomycin. Chest 1991; 99:993-99 [46]Ingrassia TS III, Ryu JH, Trastek VF, Rosenow EC III. Oxygen-exacerbated bleomycin pulmonary toxicity. Mayo Clin Proc 1991; 66:173-78 [47]Bellamy EA, Husband JE, Blaquiere RM, Law MR. Bleomycin-related lung damage: CT evidence. Radiology 1985; 156:155-58 [48]Cohen MB, Austin JH, Smith-Vaniz A, Lutzky J, Grimes MM. Nodular bleomycin toxicity. Am J Clin Pathol 1989; 92:101-04 [49]Santrach PJ, Askin FB, Wells RJ, Azizkhan RG, Merten DF. Nodular form of bleomycin-related pulmonary injury in patients with osteogenic sarcoma. Cancer 1989; 15:806-11 [50]White DA, Schwartzberg LS, Kris MG, Bosl GJ. Acute chest pain syndrome during bleomycin infusions. Cancer 1987; 59:1582-85 [51]Massin F, Fur A, Reybet-Degat O, Camus P, Jeannin L. Busulfan-induced pneumopathy. Rev Mal Respir 1987; 4:3-10 [52]Jehn U, Goldel N, Rienmuller R, Wilmanns W. Non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema complicating intermediate and high-dose Ara C treatment for relapsed acute leukemia. Med Oncol Tumor Pharmacother 1988; 5:41-7 [53]Andersson BS, Luna MA, Yee C, Hui KK, Keating MJ, McCredie KB. Fatal pulmonary failure complicating high-dose cytosine arabinoside therapy in acute leukemia. Cancer 1990; 65:1079-84 [54]Lazarus DS, Kurnick JT, Kradin RL. Alterations in pulmonary function in cancer patients receiving adoptive immunotherapy with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and interleukin-2. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990; 141:193-98 [55]Saxon RR, Klein JS, Bar MH, Blanc P, Gamsu G, Webb WR, et al. Pathogenesis of pulmonary edema during interleukin-2 therapy: correlation of chest radiographic and clinical findings in 54 patients. AJR 1991; 156:281-85 [56]Kuei JH, Tashkin DP, Figlin RA. Pulmonary toxicity of recombinant human tumor necrosis factor. Chest 1989; 96:334-38 [57]Demetri GD, Spriggs DR, Sherman ML, Arthur KA, Imamura K, Kufe DW. A phase I trial of recombinant human tumor necrosis factor and interferon-gamma: effects of combination cytokine administration in vivo. J Clin Oncol 1989; 7:1545-53 [58]Hocking DC, Phillips PG, Ferro TJ, Johnson A. Mechanisms of pulmonary edema induced by tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Circ Res 1990; 67:68-77 [59]Luedke D, McLaughlin TT, Daughaday C, Luedke S, Harrison B, Reed G, et al. Mitomycin C and vindesine associated pulmonary toxicity with variable clinical expression. Cancer 1985; 55:542-45 [60]Hoelzer KL, Harrison BR, Luedke SW, Luedke DW. Vinblastine-associated pulmonary toxicity in patients receiving combination therapy with mitomycin and cisplatin. Drug Intell Clin Pharm 1986; 20:287-90 [61]O'Donnell AE, Pappas LS. Pulmonary complications of intravenous drug abuse: experience at an inner-city hospital. Chest 1988: 94:251-53 [62]Heffner JE, Harley RA, Schabel SI. Pulmonary reactions from illicit substance abuse. Clin Chest Med 1990; 11:151-62 [63]Parran TV Jr, Jasinski DR. Intravenous methylphenidate abuse: prototype for prescription drug abuse. Arch Intern Med 1991; 151:781-83 [64]Schmidt RA, Glenny RW, Godwin JD, Hamspon NB, Cantino ME, Reichenbach DD. Panlobular emphysema in young intravenous Ritalin abusers. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991; 143:649-56 [65]Schwartz JA, Koenigsberg MD. Naloxone-induced pulmonary edema. Ann Emerg Med 1987; 16:1294-96 [66]McCarroll KA, Roszler MH. Lung disorders due to drug abuse. J Thorac Imaging 1991; 6:30-5 [67]Patel RC, Dutta D, Schonfeld SA. Free-base associated with bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Ann Intern Med 1987; 107:186-87 [68]O'Donnell AE, Mappin G, Sebo TJ, Tazelaar H. Interstitial pneumonitis associated with "crack" cocaine abuse. Chest 1991; 100:1155-57 [69]Forrester JM, Steele AW, Waldron JA, Parsons PE. Crack lung: an acute pulmonary syndrome with a spectrum of clinical and histopathologic findings. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990; 142:462-67 [70]Pare JP, Cote G, Fraser RS. Long-term follow-up of drug abusers with intravenous talcosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989; 139:233-41 [71]McLucas B. Hyskon complications in hysteroscopic surgery. Obstet Gynecol Surg 1991; 46:196-200 [72]Leake JF, Murphy AA, Zacur HA. Noncardiogenic pulmonary edema: a complication of operative hysteroscopy. Fertil Steril 1989; 48:497-99 [73]Jedeikin R, Olsfanger D, Kessler I. Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy and adult respiratory distress syndrome: life-threatening complications of hysteroscopy. Am J Obtet Gynecol 1990; 162:44-5 [74]Kitziger KJ, Sanders WE, Andrews CP. Acute pulmonary edema associated with use of low-molecular weight dextran for prevention of microvascular thrombosis. J Hand Surg 1990; 15A:902-05 [75]Kinnunen E, Viljanen A. Pleuropulmonary involvement during bromocriptine treatment. Chest 1988; 94:1034-36 [76]McElvaney NG, Wilcox PG, Churg A, Fleetham JA. Pleuropulmonary disease during bromocriptine treatment of Parkinson's disease. Arch Intern Med 1988; 148:2231-36 [77]Zeller FA, Cannon CR, Prakash UBS. Thoracic manifestations after esophageal variceal sclerotherapy. Mayo Clin Proc 1991; 66:727-32 [78]Edling JE, Bacon BR. Pleuropulmonary complications of endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy. Chest 1991; 99:1252-57 [79]Connors AF Jr. Complications of endoscopic variceal sclerotherapy. Chest 1991; 100:2-3 [80]Kavaru MS, Ahmad M, Amirthalingam KN. Hydrochlorothiazide-induced acute pulmonary edema. Cleve Clin J Med 1990; 57:181-84 [81]Biron P, Dessureault J, Napke E. Acute allergic interstitial pneumonitis induced by hydrochlorothiazide. Can Med Assoc J 1991; 145:28-34 [82]Pisani RJ, Rosenow EC III. Pulmonary edema associated with tocolytic therapy. Ann Intern Med 1989; 110:714-18 [83]Roy TM, Ossorio MA, Cipolla LM, Fields CL, Snider HL, Anderson WH. Pulmonary complications after tricyclic antidepressants. Radiology 1989; 170:667-70 [84]Varnell RM, Gowin JD, Richardson ML, Vincent JM. Adult respiratory distress syndrome from overdose of tricyclic anti-depressants. Radiology 1989; 170:667-70 [85]Cheng L, Gefter WB. Acute pulmonary edema induced by overdosage of phenothiazines. Chest 1992; 101:102-04 [86]Shannon M, Lovejoy FH Jr. Pulmonary consequences of severe tricyclic antidepressant ingestion. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 1987; 25:443-61 [87]Bedorssian CWM, Luna MA, Conklin RH, Miller WC. Alveolar proteinosis as a consequence of immunosuppression: a hypothesis based on clinical and pathologic observations. Hum Pathol 1980; 11:527-35 [88]Aymard JP, Gyger M, Lavallee R, Legresley LP, Desy M. A case of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis complicating chronic myelogenous leukemia: a peculiar pathologic aspect of busulfan lung? Cancer 1984; 53:954-56 [89]Watanabe K, Sueishi K, Tanaka K, Nagata N, Hirose N, Shigematsu N, et al. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis and disseminated atypical mycobacteriosis in a patient with busulfan lung. Acta Pathol Jpn 1990; 40:63-6 [90]Durant JR, Norgard MJ, Murad TM, Bartolucci AA, Langford KH. Pulmonary toxicity associated with bischloroethylnitrosourea (BCNU). Ann Intern Med 1979; 90:191-94 [91]Doll DC. Fatal pneumothorax associated with bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 1986; 17:294-95 [92]Hsu JR, Chang SC, Perng RP. Pneumothorax following cytotoxic chemotherapy in malignant lymphoma. Chest 1990; 98:1512-13 [93]Lombard CM, Churg A, Winokur S. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease following therapy for malignant neoplasms. Chest 1987; 92:871-76 [94]Ellis DA, Capewell SJ. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease after chemotherapy. Thorax 1986; 41:415-16 [95]Hackman RC, Madtes DK, Petersen FB, Clark JG. Pulmonary veno-occlusive disease following bone marrow transplantation. Transplantation 1989; 47:989-92 [96]Kaufman J, Komorowski R. Bronchiolitis obliterans: a new clinical-pathologic complication of irradiation pneumonitis. Chest 1990; 97:1243-44 [97]Meeker DP, Wiedemann HP. Drug-induced bronchospasm. Clin Chest Med 1990; 11:163-75 [98]Hunt LW, Rosenow EC III. Drug-induced asthma. In: Weiss EB, Stein M, eds. Bronchial asthma, 3rd ed. Boston: Little, Brown (in press) [99]Stevenson DD, Hougham AJ, Schrank PF, Goldlust MB, Wilson RR. Salsalate cross-sensitivity in aspirin-sensitive patients with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1990; 86:749-58 [100]Ameisen JC, Capron A. Aspirin-sensitive asthma. Clin Exp Allergy 1990; 20:127-29 [101]Picado C, Castillo JA, Montserrat JM, Agusti-Vidal A. Aspirin-intolerance as a precipitating factor of life-threatening attacks of asthma requiring mechanical ventilation. Eur Respir J 1989; 2:127-29 [102]Lette J, Cerino M, Laverdiere M, Tremblay J, Prenovault J. Severe bronchospasm followed by respiratory arrest during thallium-dipyridamole imaging. Chest 1989; 95:1345-47 [103]Just-Viera JO, Fischer CR, Gago O, Morris JD. Acute reaction to protamine: its important to surgeons. Ann Surg 1984; 50:52-60 [104]Toronto Aerosolized Pentamidine Study (TAPS) Group. Acute pulmonary effects of aerosolized pentamidine. Chest 1990; 98:907-10 [105]Shim CS, Williams MH Jr. Cough and wheezing from beclomethasone dipropionate aerosol are absent after triamcinolone acetonide. Ann Intern Med 1987; 106:700-03 [106]Shim C, Williams MH Jr. Cough and wheezing from beclomethasone aerosol. Chest 1987;91:207-09 [107]Quieffin J, Hunter J, Schechter MT, Lawson L, Ruedy J, Pare P, et al. Aerosol pentamidine-induced bronchoconstriction. Chest 1991; 100:624-27 [108]Katzman M, Meade W, Iglar K, Rachlis A, Berger P, Chan CK. High incidence of bronchospasm with regular administration of aerosolized pentamidine. Chest 1992; 101:79-81 [109]Nicklas RA. Paradoxical bronchospasm associated with the use of inhaled beta agonists. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1990; 85:959-64 [110]Jones G, Mierins E, Karsh J. Methotrexate-induced asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis 1991; 143:179-81 [111]Fertel D, Wanner A. Methotrexate: does it treat or induce asthma? Am Rev Respir Dis 1991; 143:1-2 [112]Hill MR, Gotz VP, Harman E, McLeod I, Hendeles L. Evaluation of the asthmogenicity of propafenone, a new antiarrhythmic drug: comparison of spirometry with methacholine challenge. Chest 1986; 90:698-702 [113]Olm M, Munne P, Jimenez MJ. Severe reactive airways disease induced by propafenone [letter]. Chest 1989; 95:1366-67 [114]Sahn SA. The pleura. Am Rev Respir Dis 1988; 138:184-234 [115]Miller WT Jr. Drug-related pleural and mediastinal disorders. J Thorac Imaging 1991; 6:36-51 [116]Byrd RP, Morris CJ, Roy TM. Drug-induced pleural effusions. J Ky Med Assoc 1991; 89:71-3 [117]Smith PR, Nacht RI. Drug-induced lupus pleuritis mimicking pleural space infection. Chest 1992; 101:268-69 [118]Reed CR, Glauser FL. Drug-induced noncardiogenic pulmonary edema. Chest 1991; 100:1120-24 [119]Rosenow EC III, Pisani RJ. Acute drug-induced lung injury. In: Fletcher J, Carlson RW, Geheb M, eds. Principles and practice of medical intensive care. Philadelphia: WB Saunders (in press) [120]Akoun GM, Cadranel JL, Rosenow EC III, Milleron BJ. Bronchoalveolar lavage cell data in drug-induced pneumonitis. Allerg Immunol (Paris) 1991; 23:245-52 [121]White DA, Rankin JA, Stover De, Gellene RA, Gupta S. Methotrexate pneumonitis: bronchoalveolar lavage findings suggest an immunologic disorder. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989; 139:18-21 [122]Akoun GM, Cadranel JL, Milleron BJ, D'Ortho MPF, Mayaud CM. Bronchoalveolar lavage cell data in 19 patients with drug-associated pneumonitis (except amiodarone). Chest 1991; 99:98-104 Edward C. Rosenow III, M.D., F.C.C.P.; Jeffrey L. Myers, M.D., F.C.C.P.; Stephen J. Swensen, M.D., F.C.C.P.; and Richard J. Pisani, M.D., F.C.C.P. From the Division of Thoracic Diseases (Drs. Rosenow and Pisani), Department of Pathology (Dr. Myers), Department of Radiology (Dr. Swensen), Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

COPYRIGHT 1992 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group