In May 2001, family physicians, obstetrician-gynecologists, anesthesiologists, nurse-midwives and childbirth educators met at the Nature and Management of Labor Pain symposium sponsored by the Maternity Center Association and New York Academy of Medicine. Participants discussed presentations on the nature of labor pain, the history of anesthesia for childbirth, maternal satisfaction with childbirth, and the role of maternal choice. Commissioned systematic reviews focused on methods of labor pain management, including nonpharmacologic techniques, parenteral opiates, epidural analgesia, paracervical block, and nitrous oxide. Part II of this two-part article focuses on the use of parenteral opioids, epidural analgesia, and other pharmacologic methods of pain relief.

Parenteral Opioids

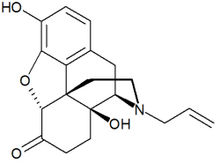

Despite common use and decades of research, there remains a paucity of data regarding the safety and efficacy of opioids for labor analgesia. Parenteral narcotics are used to alleviate pain in 39 to 56 percent of labors in U.S. hospitals. (1) Bricker and Lavender's meta-analysis (2) included all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of parenteral opioids for labor pain relief. Primary maternal outcomes included maternal satisfaction with pain relief one to two hours after drug administration and characteristics of the labor process; secondary outcomes included subsequent use of epidural analgesia, adverse symptoms (e.g., nausea, drowsiness), inability to urinate or participate in labor, cesarean delivery or instrument-assisted vaginal delivery, and maternal qualitative outcomes such as satisfaction with the overall birth experience. (2) [Evidence level A, systematic review] Neonatal outcomes focused on respiratory depression, use of naloxone (Narcan), and feeding and bonding problems.

Meperidine (Demerol) has been extensively studied, but few trials have examined the effectiveness and safety of shorter acting agents such as fentanyl (Sublimaze). Little evidence supports the use of one opioid over another. The safety and effectiveness of alternative modes of opioid administration, such as patient-controlled analgesia pumps, have not been demonstrated.

Only one RCT, (3) performed in the early 1960s, has studied parenteral opioids compared with placebo. Although opioids did provide superior pain relief and maternal satisfaction with pain management, the effect was small. Several RCTs have compared opioids with epidural analgesia. Statistically significant findings in the meta-analysis (2) indicate that the use of parenteral opioids is associated with lower rates of oxytocin augmentation, shorter stages of labor, and fewer cases of malposition and instrument-assisted delivery. Compared with epidural analgesia, parenteral opioids provide less pain relief and satisfaction with pain relief at all stages of labor. (4-6) [Reference 6--Evidence level A, RCT]

Bricker and Lavender (2) found a lack of data to measure infant safety. However, observational studies indicate that opioids are associated with neonatal respiratory depression, decreased alertness, inhibition of sucking, lower neurobehavioral scores, and a delay in effective feeding. (7,8) Long-term effects cannot be excluded.

There is a need for research that compares opioids with other methods of labor pain management such as continuous support and hydrotherapy. Outcomes should focus on pain experience and maternal satisfaction, but also on labor, and neonatal and adverse effects.

Epidural Analgesia

Epidural analgesia is an effective method of pain management that is adaptable to the varied pain patterns encountered by women during labor. (9) The increasing popularity of epidural analgesia may be a result of its greater pain-relief efficacy compared with that of parenteral opioids and its ability to meet current social, logistic, and political demands. A joint position statement (10) from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Society of Anesthesiologists reflects a prevailing viewpoint: "Labor results in severe pain for many women. There is no other circumstance where it is considered acceptable for a person to experience untreated severe pain, amenable to safe intervention, while under a physician's care. ...[M]aternal request is a sufficient medical indication for pain relief during labor."

Epidural local anesthetics theoretically could block 100 percent of labor pain if used in large volumes and high concentrations. However, pain relief is balanced against other goals such as walking during the first stage of labor, pushing effectively in the second stage, and minimizing maternal or neonatal side effects. Changes in epidural drugs and techniques have been developed to optimize pain control while minimizing side effects. To decrease motor blockade, bupivacaine (Sensorcaine) and ropivacaine (Naropin) have replaced lidocaine (Xylocaine), and drug concentrations have been lowered. (9)

Administration of an intrathecal opioid injection before continuous epidural infusion is known as combined spinal epidural (CSE) analgesia, (11) or the walking epidural. However, women who receive this type of epidural often are not able to walk because of substantial motor blockade and the need for continuous fetal monitoring after epidural placement. Advantages of CSE include rapid onset of pain relief and the potential for the intrathecal medication to suffice as a sole anesthetic in women who are likely to deliver within two or three hours of receiving it. (12)

EFFECTS ON LABOR OUTCOMES

Two systematic reviews of the effects of epidural analgesia on labor were presented at the symposium. The reviews were rigorously constructed, but they used different methodologies and came to somewhat different conclusions. Lieberman and O'Donoghue (13) reviewed high-quality observational studies in addition to RCTs. Leighton and Halpern (14) reviewed only RCTs and used formal meta-analysis techniques.

Both reviews (13,14) concluded that epidural analgesia increases the duration of the second stage of labor, rates of instrument-assisted vaginal deliveries, and the likelihood of maternal fever. [Reference 14--Evidence level A, systematic review] Neither review demonstrated that the use of epidural analgesia increased rates of cesarean delivery compared with use of parenteral opioids, although Lieberman and O'Donoghue (13) cautioned that data may not be sufficient to rule out a possible association. The authors cited weaknesses in the RCTs, including high percentages of women who did not receive their assigned analgesic method. The 30 to 50 percent crossover rates in several studies make it difficult to interpret risk for cesarean delivery. (5,6,15-17) In addition, some study settings had lower cesarean delivery rates as a result of enrolling only women who were in active labor (3 to 5 cm dilation) (6,15) and younger populations (6,15,16) than most obstetric practices, which weakens the generalizability of findings.

In Leighton and Halpern's review, (14) the effects of epidurals on maternal fever could not be established because the control groups in the reviewed trials received intravenous meperidine, which may have a hypothermic effect. A major concern regarding the use of epidural analgesia is that epidural-induced maternal fever unnecessarily increases work-ups for neonatal sepsis. (18) This appears to be the case in hospitals that have a more aggressive protocol for initiating such work-ups. (14) A summary of the effects of epidural analgesia is provided in Table 1. (13,14)

A systematic review (14) examined the effects of specific modifications of epidural timing, technique, and dosing. According to the review, two small RCTs (19,20) found no difference in mode of delivery when epidural analgesia was initiated early (mean dilation 3.5 to 4 cm) or late (mean dilation 5 cm). These RCTs were limited by the minimal differences in timing of epidural initiation between groups. Observational studies generally showed a slightly higher rate of cesarean delivery when epidurals were administered early, with relative risk increased by 1.6 to 4.7, depending on the study. (14) The Symposium Steering Committee concluded that delaying administration of epidural analgesia may reduce rates of cesarean delivery, but that data are insufficient to allow a definitive conclusion to be reached. (21)

Data also are insufficient to determine whether discontinuing epidural infusions in women with more than 8 cm dilation improves pushing and increases rates of spontaneous vaginal delivery. There is no evidence that decreasing bupivacaine concentration to less than 0.125 percent or using a continuous infusion (rather than repeated boluses) or CSE improves delivery outcomes. (13)

SIDE EFFECTS AND CARE DURING LABOR

A review (22) of 19 RCTs provides an overview of the side effects of epidural analgesia. Because the trials compared a wide variety of drugs and protocols, the data could not be used for a quantitative meta-analysis. Common side effects include hypotension, impaired motor function with inability to walk, and the need for urinary catheterization. Uncommon side effects (i.e., effects that occur in less than 10 percent of women) include pruritus, nausea and vomiting, and sedation.

The review concluded that although serious complications of epidural analgesia are rare, the use of epidural analgesia during labor is associated with multiple side effects that require monitoring and other interventions. Nursing staff need increased training to manage the more complex care required for women who receive epidural analgesia. Research is needed to determine whether time spent monitoring technical aspects of labor analgesia detracts from traditional supportive nursing activities.

The review also studied the use of delayed pushing as a labor management strategy in women with epidurals. Three RCTs of nulliparous women who received epidural analgesia compared conventional early pushing (i.e., starting at full dilation regardless of fetal station) with delayed pushing (i.e., waiting one to three hours after complete dilation). The largest trial found that delayed pushing reduced the risk of difficult operative vaginal or cesarean deliveries. (23) [Evidence level A, RCT] Women with a high fetal station or a posterior or transverse presentation were most likely to benefit from delayed pushing. Neonatal morbidity rates were similar except for an abnormal umbilical artery pH that was more common in infants born after delayed pushing.

NITROUS OXIDE

Nitrous oxide is widely used for obstetric analgesia in most developed countries, with the exception of the United States. More than 60 percent of women in Finland and the United Kingdom use nitrous oxide for pain relief during labor. (24) The most commonly used mixture, a 50-50 blend of nitrous oxide and oxygen called Entonox, can be used in any stage of labor. The full analgesic effect usually is felt 50 seconds after inhalation. Entonox generally is self-administered as needed, but it can be administered continuously with medical supervision.

A systematic review of 11 RCTs comparing Entonox with placebo or other inhaled agents showed that Entonox provided a consistent but moderate analgesic effect. (25) [Evidence level B, systematic review of lower quality studies] Approximately one half of study participants said Entonox provided significant pain relief. Adverse effects included nausea, vomiting, and poor recall of labor.

Paracervical Block

The injection of local anesthetics into paracervical tissue for first-stage labor analgesia frequently was used in the United States during the 1960s and 1970s. Its use decreased after it was associated with fetal bradycardia and epidural analgesia became increasingly available. Four RCTs included in a systematic review (26) demonstrated that paracervical block was 75 percent effective in achieving good or excellent pain relief during the first stage of labor.

The incidence of postparacervical block bradycardia (PPCBB) ranged from zero to 40 percent. (26) Despite case reports of adverse outcomes, none of the women who participated in the RCTs had emergency cesarean deliveries or adverse neonatal outcomes. The etiology of PPCBB is unknown; proposed mechanisms include inadvertent neonatal injection, vasoconstriction of the uterine or umbilical arteries, and elevated uterine tone or toxicity as a result of fetal absorption.

Paracervical blocks have a short duration of action, which requires repeated blocks during the first stage of labor, and they cannot be administered in the second stage of labor because of the position of the fetal head. None of the studies revealed adverse effects of paracervical block on the progression of labor, likelihood of vaginal delivery, or neonatal outcomes unrelated to PPCBB. Uncommon complications include maternal hematoma or abscess and sacral neuropathy.

Paracervical block is effective in the first stage of labor and does not require anesthesia personnel for administration. Because of concerns about PPCBB, use of paracervical block likely will remain limited. It should not be used in women with nonreassuring fetal heart tracings or uteroplacental insufficiency because the significance of PPCBB in this setting is difficult to determine.

Patterns of Pain and Issues of Choice

Women in the United States have fewer options for labor pain management than women in countries such as Canada (27) and the United Kingdom. (28) An attempt to analyze the factors responsible for the limited choices of obstetric analgesia in the United States yielded few data. (29) Temporal studies show an increase in epidural usage and diffusion to smaller hospitals from 1981 to 1997. (30)

The availability of various methods of pain relief is based on complex interactions of provider and patient preferences and economic factors. It is unclear if the high use of epidural analgesia is a true preference among women in the United States or if it is chosen because the only other option presented is parenteral opioids. Research regarding which labor pain options women would choose if they had a greater range of choices would be useful.

The authors indicate that they do not have any conflicts of interests. Sources of funding: Dr. King's work is funded by an Academic Administrative Units in Primary Care Grant (#5-D12-HP00055) from the Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration and the Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Faculty Scholar Program.

REFERENCES

(1.) Hawkins JL, Beaty BR, Gibbs CP. Update on obstetric anesthesia practices in the U.S. Anesthesiology 1999;91:A1060.

(2.) Bricker L, Lavender T. Parenteral opioids for labor pain relief: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186(Suppl 5):S94-109.

(3.) DeKornfeld TJ, Pearson JW, Lasagna L. Methotrimeprazine in the treatment of labor pain. N Engl J Med 1964;270:391-4.

(4.) Bofill JA, Vincent RD, Ross EL, Martin RW, Norman PF, Werhan CF, et al. Nulliparous active labor, epidural analgesia, and cesarean delivery for dystocia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997;177:1465-70.

(5.) Loughnan BA, Carli F, Romney M, Dore CJ, Gordon H. Randomized controlled comparison of epidural bupivacaine versus pethidine for analgesia in labour. Br J Anaesth 2000;84:715-9.

(6.) Sharma SK, Sidawi JE, Ramin SM, Lucas MJ, Leveno KJ, Cunningham FG. Cesarean delivery: a randomized trial of epidural versus patient-controlled meperidine analgesia during labor. Anesthesiology 1997;87:487-94.

(7.) Riordan J, Gross A, Angeron J, Krumwiede B, Melin J. The effect of labor pain relief medication on neonatal suckling and breastfeeding duration. J Hum Lact 2000;16:7-12.

(8.) Nissen E, Lilja G, Matthiesen AS, Ransjo-Arvidsson AB, Uvnas-Moberg K, Widstrom AM. Effects of maternal pethidine on infants' developing breast feeding behaviour. Acta Paediatr 1995;84:140-5.

(9.) Caton D, Frolich MA, Euliano TY. Anesthesia for childbirth: controversy and change. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186(Suppl 5):S25-30.

(10.) ACOG committee opinion. Pain relief during labor. No. 231, February 2000. Obstet Gynecol 2000;95:1.

(11.) Collis RE, Baxandall ML, Srikantharajah ID, Edge G, Kadim MY, Morgan BM. Combined spinal epidural (CSE) analgesia: technique, management, and outcome of 300 mothers. Int J Obstet Anesth 1994; 3:75-81.

(12.) Fontaine P, Adam P, Svendsen KH. Should intrathecal narcotics be used as a sole labor analgesic? A prospective comparison of spinal opioids and epidural bupivacaine. J Fam Pract 2002;51:630-5.

(13.) Lieberman E, O'Donoghue C. Unintended effects of epidural analgesia during labor: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186(Suppl 5):S31-68.

(14.) Leighton BL, Halpern SH. The effects of epidural analgesia on labor, maternal, and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186(Suppl 5):S69-77.

(15.) Ramin SM, Gambling DR, Lucas MJ, Sharma SK, Sidawi JE, Leveno KJ. Randomized trial of epidural versus intravenous analgesia during labor. Obstet Gynecol 1995;86:783-9.

(16.) Clark A, Carr D, Loyd G, Cook V, Spinnato J. The influence of epidural analgesia on cesarean delivery rates: a randomized, prospective clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;179:1527-33.

(17.) Howell CJ, Kidd C, Roberts W, Upton P, Lucking L, Jones PW, et al. A randomised controlled trial of epidural compared with non-epidural analgesia in labour. BJOG 2001;108:27-33.

(18.) Lieberman E, Lang JM, Frigoletto F Jr, Richardson DK, Ringer SA, Cohen A. Epidural analgesia, intrapartum fever, and neonatal sepsis evaluation. Pediatrics 1997;99:415-9.

(19.) Chestnut DH, Vincent RD Jr, McGrath JM, Choi WW, Bates JN. Does early administration of epidural analgesia affect obstetric outcome in nulliparous women who are receiving intravenous oxytocin? Anesthesiology 1994;80:1193-200.

(20.) Chestnut DH, McGrath JM, Vincent RD Jr, Penning DH, Choi WW, Bates JN, et al. Does early administration of epidural analgesia affect obstetric outcome in nulliparous women who are in spontaneous labor? Anesthesiology 1994;80:1201-8.

(21.) Caton D, Corry MP, Frigoletto FD, Hopkins DP, Lieberman E, Mayberry L. The nature and management of labor pain: executive summary. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186(Suppl 5):S1-15.

(22.) Mayberry LJ, Clemmens D, De A. Epidural analgesia side effects, co-interventions, and care of women during childbirth: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186(Suppl 5):S81-93.

(23.) Fraser WD, Marcoux S, Krauss I, Douglas J, Goulet C, Boulvain M. Multicenter, randomized, controlled trial of delayed pushing for nulliparous women in the second stage of labor with continuous epidural analgesia. The PEOPLE (Pushing Early or Pushing Late with Epidural) Study Group. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;182:1165-72.

(24.) Kangas-Saarela T, Kangas-Karki K. Pain and pain relief in labour: Parturients' experiences. Int J Obstet Anesth 1994;3:67-74.

(25.) Rosen MA. Nitrous oxide for relief of labor pain: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186 (Suppl 5):S110-26.

(26.) Rosen MA. Paracervical block for labor analgesia: a brief historic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002; 186(Suppl 5):S127-30.

(27.) Levitt C. Survey of routine maternity care and practices in Canadian hospitals. Ottawa: Canadian Institute of Child Health, 1995.

(28.) Findley I, Chamberlain G. ABC of labour care. Relief of pain. BMJ 1999;318:927-30.

(29.) Marmor TR, Krol DM. Labor pain management in the United States: understanding patterns and the issue of choice. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002;186 (Suppl 5):S173-80.

(30.) Hawkins JL, Gibbs CP, Orleans M, Martin-Salvaj G, Beaty B. Obstetric anesthesia work force survey, 1981 versus 1992. Anesthesiology 1997;87:135-43.

Members of various family practice departments develop articles for "Practical Therapeutics." This article is one in a series coordinated by the University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City. Guest editor of the series is Stephen Ratcliffe, M.D., M.S.P.H.

This is part II of a two-part article on managing labor pain. Part I, "Nonpharmacologic Pain Relief," appears in this issue on page 1109.

LAWRENCE LEEMAN, M.D., M.P.H., University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque, New Mexico PATRICIA FONTAINE, M.D., M.S., University of Minnesota School of Medicine, Minneapolis, Minnesota VALERIE KING, M.D, M.P.H., University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, North Carolina MICHAEL C. KLEIN, M.D., University of British Columbia Faculty of Medicine, Vancouver, British Columbia STEPHEN RATCLIFFE, M.D., M.S.P.H., Lancaster General Family Practice Residency, Lancaster, Pennsylvania

COPYRIGHT 2003 American Academy of Family Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group