CourtCase

A S BACK SURGERY GOES TRAGICALLY WRONG.

IN 1995, Marshall 0. Welch, Jr., 37, had been working at the Southern Neurologic Institute for almost 3 years. An RN, he cared for patients of Franklin Epstein, a neurosurgeon.

Welch had had severe backaches for about 5 years. He was taking significant amounts of prescribed pain medication, including Tylox (acetaminophen, 500 mg, and oxycodone HCI, 5 mg) and Vicodin (acetaminophen, 500 mg, and hydrocodone bitartrate, 5 mg). He consulted Dr. Martin Greenberg, Epstein's partner, about his unrelenting back pain; Greenberg recommended surgery. Melvyn Haas, a neurologist he saw for a second opinion, agreed that surgery was indicated.

Welch asked Epstein to operate, with Greenberg assisting. During surgery, a cell saver would be used to collect and reinfuse his lost blood because he wanted to avoid blood transfusions.

Hemoglobin levels and pain medications

On Thursday, February 22, 1996, Welch was admitted to the Aiken Regional Medical Center. His preoperative hemoglobin level was 14.4 grams/dl. During surgery, he lost approximately 2,100 ml of blood. He received approximately 2,500 ml of fluid and 625 ml of blood from the cell saver. While he was still in the OR, the nurseanesthetist applied a 50-mcg/hour fentanyl patch, as Epstein ordered, to control postoperative pain.

In the postanesthesia care unit, Welch's hemoglobin level was 12 grams/d1. He complained of pain and received 2.5 mg of hydromorphone HCI (Dilaudid), 25 mg of promethazine HCl (Phenergan), and 1 mg of diazepam (Valium). The nurse applied another 50-mcg/hour fentanyl patch because the original one had fallen off.

On Friday morning, Welch's hemoglobin level was 8.6 grams/dl. Epstein concluded that Welch was experiencing fluid overload and that the hemoglobin decrease wasn't a problem because Welch didn't have shortness of breath or chest pain and his mental status and urine output were good.

Over the course of that day, Welch received six injections of Dilaudid, four of Phenergan, and an oral dose of Valium while still wearing the fentanyl patch. No additional hemoglobin levels were ordered.

On Saturday morning, when Welch's hemoglobin level was rechecked twice, it was 6.9 grams/dl and 6.6 grams/dl. Darlene Colvin, the charge nurse in the unit, notified Epstein, who decided to wait and check it again later because Welch's blood pressure (BP) was normal and he was alert and urinating.

Taking action

Haas was taking calls for Epstein on Saturday, so he called to check on Welch at 4:20 p.m. Learning that his hemoglobin was 6.5 grams/dl and he had a fever, Haas ordered two blood cultures and the transfusion of two units of packed cells. Learning of the transfusion order, Welch asked Colvin to call Epstein at home.

Colvin reached Epstein and told him about the order. She also reported that Welch had developed puffiness to the left of his incision and that his temperature was increasing. She said Welch was "very rigid" and complained of discomfort in the groin area.

Epstein decided to "hold off" on the transfusion because Welch was thinking clearly and urinating and his BP was stable. He didn't think blood cultures were necessary either. He canceled the transfusion and all lab studies and gave an order to increase the fentanyl patch to 100 mcg; Valium, 5 mg P.O. every 8 hours; prochlorperazine (Compazine), 10 mg P.O. every 6 to 8 hours as needed; and docusate sodium (Colace), 100 mg P.O. b.i.d.

At 5:40 p.m., Welch received Dilaudid and Phenergan. Because he was resting comfortably, his primary nurse decided not to apply the additional fentanyl patch and Colvin agreed with the decision.

Time to transfuse

At about 6:25 p.m., Haas learned that Epstein had canceled the transfusion. Haas ordered a hemoglobin level, which was now 6.0 grams/dl. Feeling that Welch needed a transfusion, he asked the nurse to page Epstein. Epstein ordered three units of packed red blood cells, application of the fentanyl patch "now," and finger-stick hemoglobin and hematocrit levels after the transfusion.

The nurses had difficulty inserting an IN. line for the transfusion. Martha Ulmer, an ICU nurse, finally succeeded and the transfusion was started in the early hours of Sunday morning. According to Ulmer, there wasn't much of a blood return, possibly signaling low blood volume.

At 2, 4, and 5:30 a.m., Welch was easily aroused, alert, and oriented. But at 6 a.m., the nurses couldn't rouse him. His skin, mouth, and tongue were very pale. While the nurses were in his room, his pulse and respirations stopped.

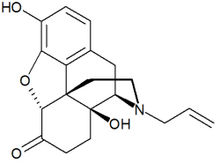

The nurses called a code, administered naloxone HCl (Narcan), and administered CPR. Welch was transferred to the ICU and maintained on life support. He received six more units of blood and other fluids, but never regained consciousness and exhibited no brain activity. He was removed from life support on February 29.

Malpractice charge

Kimberly Johnson Welch, representing Welch's estate, sued Epstein and Southern Neurologic Institute for medical malpractice resulting in wrongful death. Several expert witnesses testified that Epstein had deviated from the standard of care and probably caused Welch's death. Victoria Samuels, a neurosurgeon, testified that low blood volume with anemia is "a lethal combination in general surgery." Plus, the body's defenses were "markedly depressed" because of the massive amount and types of medicine Welch was receiving.

The jury imposed actual and punitive damages of over $6.9 million against Epstein. He appealed. Among his several claims, he said that the facts didn't support the jury's findings and that $3.9 million in punitive damages would violate South Carolina law by causing his economic ruin.

The appellate court upheld the lower court's decisions. It said that the evidence supported the jury's verdict and justified punitive damages. The fact that the amount exceeded Epstein's net worth didn't violate state law because the law requires the jury only to consider the defendant's net worth before imposing the penalty.

Source: Kimberly Johnson Welch v. Franklin M. Epstein, Martin Greenberg, and Southern Neurologic Institute (South Carolina Court of Appeals, July 31, 2000).

Copyright Springhouse Corporation Dec 2001

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved