Two uncommonly diagnosed tapeworms, Dipylidium caninum, the dop tapeworm, and Hymenolepis diminuta, the rodent tapeworm, have occasionally been found in humans. Both infections are caused by the ingestion of infected fleas. Several different parasites are transmitted from dogs and cats to people, including Toxoplasma, Giardia, Toxocara (visceral larva migrans), Ancylostoma (cutaneous larva migrans), Dirofilaria, Echinococcus, and Dipylidium. [1] Dipylidium caninum tapeworms are quite prevalent in both domestic and feral dogs and cats and may be the most common parasite in domestic dogs and cats. [2-4] Because gravid segments of the tapeworms (proglottids) passed by infested children are small, white, and motile, they may often be mistaken for adult pinworms (Figure 1). The following case report illustrates a typical presentation of Dipylidium in an infant.

Case Report

A concerned mother called requesting treatment for her 6-month-old female infant who she said had pinworms. Her child had been passing large numbers of worms while the infant was active and awake. She appeared to be healthy otherwise. The worms were described as 1/2-in. long, white, motile, and freely passing from the anus in large numbers.

A stool sample, which was examined for ova and parasites, and a Scotch tape test were nondiagnostic. A trial of pyrantel pamoate (11 mg/kg in a single dose) was attempted, but the child continued to pass "worms." A sample was collected from the child and submitted to the University of Kentucky for analysis. Dipylidium caninum infection was confirmed by the identification of a typical gravid proglottid. The infant was then treated with one 500-mg table of niclosamide, crushed and mixed with applesauce. No further worm segments were passed. A follow-up stool sample taken 3 months later was negative for ova and parasites.

Discussion

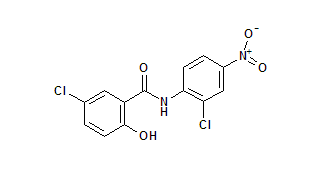

Pinworms are often diagnosed and their treatment prescribed over the telephone. Dipylidium caninum, although infrequently found in infants, may be improperly diagnosed unless proglottids, or egg packets, are visualized and identified. The proglottids are shaped like cucumber seeds, 1.3 X 0.3 cm in size, narrow at both ends, and broad in the middle.

Gravid segments of Dipylidium caninum with egg packets (Figure 2) either are passed in the stool of the infected host or simply migrate out from the rectum onto the perianal tissues. Bedding and perianal hairs may then be contaminated with viable eggs. Larval forms of dog fleas, cat fleas, and occasionally human fleas then ingest the eggs. In the flea midgut, the eggs hatch and eventually develop into an infectious metacestode stage. Adult fleas are then eaten by dogs or cats, resulting in infestation. Infants and other accidental hosts appear to acquire the infection by ingesting fleas or flea parts while in close contact with infected household pets. Adult worms may be from 6 to 30 in. in length and have up to 175 segments. Each segment may contain 15 to 25 eggs. [3-5]

As illustrated by this report, a stool for ova and parasites may not be helpful in diagnosing Dipylidium unless actual proglottids are discovered, as the gravid segments do not usually release eggs within the intestine of the host. [6]

Dipylidium has been reported in Europe as well as in the United States. Its distribution appears to be worldwide, although published case reports in the United States have been infrequent. [4-6] It has been speculated that infants may rapidly develop resistance, which may explain the paucity of cases in older children and adults. The lack of direct exposure to infected animals may also be a factor contributing to the infrequent diagnosis in adults. [6] The majority of human infestations have been in persons younger than 8 years old and have most often been found in the southern states. [6-7]

The prevalence of the parasite and the proximity of infected animals to humans would suggest that transmission occurs more frequently than is recognized. [6,7] It may be that infection is often asymptomatic and perhaps self-limited; therefore, undiagnosed infections in many individuals may resolve without recognition of symptoms or complications.

Symptoms of Dipylidium infestation have been reported infrequently but are generally described as mild and nonspecific and include abdominal pain, diarrhea, pruritus ani, failure to gain weight, and irritability. [5,6] With so few case reports, inferring cause and effect from such non specific symptoms must be suspect. [1,2]

Treatment

The drug of choice currently is niclosamide. [8-10] A single dose of 1 g is appropriate for a child weighing 11 to 34 kg, and 1 1/2 to 2 g for a child weighing more than 34 kg. No dosage schedule is universally suggested for a child who weights less than 11 kg. Jones [8] reported 43 cases of Dipylidium treated with niclosamide; in the 13 cases for which a follow-up examination was done, the children were found to be free of parasites. Of over 80 patients receiving niclosamide for either Dipylidium or Hymenolepis, only four complained of side effects: one experienced abdominal pain and diaphoresis, and three experienced nausea.

Niclosamide is the first-line agent for most cestode infections in humans (Diphyllobothrium latum, Taenia saginata, and Taenia solium). Alternative treatment with paromomycin or praziquantel is still under investigation for this diagnosis. Treatment of infected infants must be accompanied by efforts to rid the local primary hosts of worms and to eradicate fleas. In animals, praziquantel is the drug of choice; niclosamide is considered less reliable. [3,9,10]

References

[1] Elliot DE, Tolle SW, Goldberg L, Miller JB. Pet associated illness. N Engl J Med 1985; 313:985-95.

[2] Marx M. Parasites, pets and people. Prim Care 1991; 18:153-65.

[3] Boreham RE, Boreham PFL. Dipylidium caninum: Life cycle, epizootiology, and control. Compend cont educ pract vet 1990; 12:667-74.

[4] Bartocas CS, Von Gravenitz A, Blodgett F. Dipylidium infection in a six-month old infant. J Pediatr 1966; 69;814-15.

[5] Currier RW, Kinzer GM, DeSheilds E. Dipylidium caninum infection in a 14-month-old child. South Med J 1973; 66:1060-2.

[6] Turner JA. Human dipylidiasis (dog tapeworm infection) in the United States. J Pediatr 1962; 61:763-8.

[7] Anderson OW. Dipylidium caninum infestation. Am J Dis Child 1988; 116:328-30.

[8] Jones WE. Niclosamide as a treatment for Hymenolepis and Dipylidium caninum infection in man. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1979; 28:300-2.

[9] Drugs for parasitic infections. Med Lett 1984; 26:27-34.

[10] Sanford JP. Guide to West Bethesda, Md: Antimicrobial Therapy Inc, 1990:84.

COPYRIGHT 1992 Dowden Health Media, Inc.

COPYRIGHT 2004 Gale Group