Learn how to reduce the risks of life-threatening complications from blood in the subarachnold space.

WHILE COOKING DINNER this evening, Mary Soncini, 42, suddenly clutches her head and tells her husband she's having "the worst headache of my life." Knowing that something's seriously wrong, he calls 911.

The Soncinis are about to learn that the cause of her terrible headache is a subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. This lifethreatening condition affects 25 to 30 thousand people in the United States each year. One out of every 10 dies before reaching the emergency department (ED). Half of those who survive die of complications; only about a fourth of those who recover have mild deficits or none at all.

Irritated meninges

When Mrs. Soncini arrives in the ED, her BP is 150/80; pulse, 110; respirations, 22; temperature, 99.7 deg F (37.6 deg C). She's alert and oriented to person, place, and date and she's moving all extremities equally with good sensation and motor strength. Her pupils are equal and reactive and her cranial nerve assessment is normal. Her deep tendon reflexes are +2 in all extremities.

Besides a severe headache, Mrs. Soncini complains of sensitivity to light and a stiff neck. Her Kernig's and Brudzinski's signs are positive. All may signal meningeal irritation that occurs with subarachnoid hemorrhage. (For a comprehensive list, see Signs and Symptoms of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage.)

A computed tomography (CT) scan of her head confirms subarachnoid hemorrhage. The physician orders a stat arteriogram to study her cerebral vessels. Before the procedure, the nurse draws blood for a complete blood cell count, prothrombin and activated partial thromboplastin times, and electrolyte, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine levels. Assessing Mrs. Soncini's renal function is essential to make sure her kidneys will be able to eliminate the dye she'll receive during the arteriogram.

The arteriogram shows a 5-mm left middle cerebral artery saccular aneurysm, the most common type of cerebral aneurysm. Also known as a "berry" aneurysm, it has a well-defined stem and berry-like outpouching of the medial layer of the arterial wall. Fortunately, Mrs. Soncini isn't among the 20% of patients who have more than one aneurysm.

Whys and wherefores of cerebral aneurysm

Rupture of a cerebral aneurysm is the most common cause of blood in the subarachnoid space. Other causes include rupture of an arteriovenous malformation, ventricular cerebral hemorrhage with extension into the subarachnoid space, trauma, hypertension, and cocaine abuse. Sometimes the cause can't be determined.

Most cerebral aneurysms occur at the bifurcation of major vessels that make up the circle of Willis and lie within the subarachnoid space. Why they form and rupture remains unclear. Extrinsic, congenital, and genetic factors may be involved. Because the incidence increases with aging and aneurysms frequently develop at sites where hemodynamic stresses are greatest, they may be acquired lesions.

Cerebral aneurysms sometimes affect families and are associated with certain pathologies, such as polycystic kidney disease, so genetic influences may contribute to their development. Other possible causes include weakness, postnatal deterioration, or trauma to the vessel's intimal layer; arterial sclerosis; infection; and inflammation.

When surgery can help

To prevent serious complications of cerebral aneurysm, the patient should be placed on aneurysm precautions:

* Place her in a quiet, dark room.

* Limit visitors and environmental stimuli.

* Manage her pain as ordered.

* Tell her not to blow her nose, cough, or sneeze, if possible, and to avoid bearing down in any way.

* Administer stool softeners.

* Monitor for and manage pain and stress.

* Maintain BP within prescribed parameters.

The patient should also undergo surgery as soon as possible. Generally, a metal clip is placed on the neck of the aneurysm to prevent further blood flow to the aneurysm. Other surgical options include wrapping the aneurysm and placing a coil in it. (See A Coil to Correct an Aneurysm.)

If the patient's neurologic status is poor, she'll need medical treatment before surgery to decrease her risks. According to the Hunt and Hess scale commonly used to grade neurologic status, anyone with grade 1 or 2 is considered a candidate for immediate surgery. (See Grading an Aneurysm.) Mrs. Soncini is grade 2.

The physician tells Mrs. Soncini and her husband that she has a cerebral aneurysm and that surgery offers her the best chance of resuming an independent lifestyle. She gives informed consent and has the procedure within hours.

Her surgery and postoperative course in the intensive care unit (ICU) are uneventful. On her third postoperative day, she's eating a regular diet and is transferred to the medical/surgical unit.

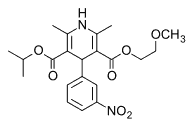

Mrs. Soncini arrives alert and oriented. She's moving all extremities with a motor score of 5/5, her sensation is intact, and she doesn't have cranial nerve deficits. (Assessment Aids reviews how to evaluate strength, deep tendon reflexes, and cranial nerve deficits.) She has a full head dressing with an underlying horseshoe incision with staples. Her JacksonPratt drain was discontinued on postoperative day 2, and her staples will be removed on day 10. To reduce the risk of vasospasm and seizures, she's taking nimodipine

(Nimotop) and phenytoin.

On guard against complications

As Mrs. Soncini's primary nurse, you follow routine seizure precautions and carefully monitor for changes in her neurologic status. Urgent complications may include rebleeding, vasospasm, hydrocephalus, and seizures. Monitor for signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) with every assessment. Neurologic deterioration is commonly due to increased ICP caused by rebleeding or hydrocephalus.

Rebleeding. This is the most lethal complication of cerebral aneurysm, most commonly occurring within 10 days after the initial hemorrhage. The cause may be fibrinolysis, which dissolves the clot, or high arterial BP Rebleeding generally isn't a risk after surgery unless the surgical clip is dislocated.

When rebleeding occurs, more blood enters the subarachnoid space, increasing ICP. Your patient may have an acute change in level of consciousness (LOC), headache, seizure, nausea, vomiting, change in motor assessment, or change in pupil size. If she's had a ventriculostomy, you'll see an increased volume of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) drainage with bright red blood; the ICP monitor will show a sudden pressure increase.

Vasospasm. Caused by blood in the subarachnoid space that becomes an irritant, vasospasm narrows blood vessels in the brain, decreasing perfusion to the areas they supply with blood. It can occur whether the patient has surgery or not. The amount of blood can directly affect the degree of vasospasm.

Typically occurring in 30% to 60% of cases between postoperative days 4 and 12, vasospasm has a mortality rate as high as 50%. If it isn't treated rapidly, it can cause cerebral ischemia or cerebral anoxia, leading to severe mental and physical deficits or death.

Any patient with subarachnoid hemorrhage should be started on the calcium channel blocker nimodipine within 96 hours of bleeding and receive it for 21 days to prevent vasospasm. It also helps prevent seizures, probably by dilating small arteries to improve collateral circulation. The typical nimodipine dosage is 60 mg every 4 hours by mouth. If the patient has hypotension, she can receive 60 mg every 6 hours or 30 mg every 4 hours.

Thoroughly assess Mrs. Soncini's LOC, orientation, pupils, motor abilities, and cranial nerve integrity at least every 4 hours. Signs of vasospasm include confusion, agitation, speech difficulties, lethargy, restlessness, disorientation, and motor weakness. Because vasospasm is a dynamic situation, her neurologic status may change frequently with the degree of spasm.

Mrs. Soncini should have a transcranial Doppler ultrasound study daily or if her neurologic status changes. This measures the velocity of blood flow, which increases if vasospasm constricts the vessel.

Your clinical examination can indicate which cerebral vessel is affected by vasospasm, based on the following focal deficits:

* anterior cerebral artery, leg weakness

* middle cerebral artery, arm weakness (speech disturbances if the dominant hemisphere is involved)

* posterior cerebral artery, weakness of the face or cranial nerve deficit.

Several approaches are used to treat cerebral vasospasm. A common choice is hyperdynamic therapy, also known as triple-H therapy. Initiated when the patient is at high risk or has signs and symptoms of vasospasm, triple-H therapy relies on induced hypertension, hemodilution, and hypervolemia to increase cerebral blood flow. (For a rundown of the techniques, see Healing with Triple-H Therapy

When triple-H therapy is unsuccessful, cerebral angioplasty may be used to combat vasospasm. This involves threading a catheter via the femoral artery to the cerebral vessels. When the affected vessel is located, a balloon is inflated to dilate it and prevent further neurologic deterioration.

Hydrocephalus. A patient with subarachnoid hemorrhage also runs the risk of acute or chronic hydrocephalus before or after surgery. Blood in the subarachnoid space may clog the villi that absorb CSF, causing the volume of CSF in the ventricle to increase, along with ICP. Signs and symptoms of hydrocephalus include change in LOC, shuffling gait, and incontinence. A CT scan can confirm the diagnosis.

A patient with hydrocephalus needs a ventriculostomy to remove the excess fluid and lower ICP If this doesn't resolve the hydrocephalus, she'll receive a permanent ventriculo-peritoneal shunt for long-term drainage.

Seizures. Blood in the subarachnoid space is an irritant that can trigger seizures. If a patient has a seizure and her aneurysm hasn't been clipped, her risk of rebleeding increases. To reduce seizure risk, patients typically receive prophylactic phenytoin or phenobarbital for 3 months.

Responding to complications

Four days after Mrs. Soncini's initial hemorrhage, you note weakness in her right arm with 3/5 motor strength. Her speech is garbled. Knowing that she may be experiencing vasospasm, you alert the physician. He orders stat transcranial ultrasonography, which indicates increased velocities in her left middle cerebral artery, confirming vasospasm. In response to the emergency, you call the ICU and arrange to transfer her.

As ordered, the ICU nurse initiates triple-H therapy by administering 0.9% sodium chloride solution intravenously (IN.) at 150 ml/hour. When Mrs. Soncini's status doesn't improve, the physician orders a hematocrit level, which is 29%. He orders a type and crossmatch for one unit of packed red blood cells to raise the level to 30% to 33%.

Shortly after the transfusion, the strength in Mrs. Soncini's right arm improves to grade 4/5. Her neurologic status improves with a systolic BP of 160 mm Hg, but she continues to have difficulty speaking.

Mrs. Soncini improves over the next few days. She's weaned from I.V. fluids and the nurses continue to evaluate her neurologic status. As her condition stabilizes, she begins rehabilitation with physical, occupational, and speech therapy. The goals are to achieve independence with functional mobility, cognition, self-care, and speech.

Physical therapy focuses on bed and wheelchair mobility, sitting balance, transfers, and gait. Strengthening exercises allow functional progression.

Occupational therapy focuses on deficits in Mrs. Soncini's functional cognition, perception, and vision as they affect her activities of daily living. She works on developing her fine motor skills, strengthening her upper extremities, and learning functional transfers.

Speech therapy helps develop her ability to understand and communicate speech. The therapist evaluates her swallowing function and makes appropriate dietary recommendations to prevent aspiration.

When Mrs. Soncini's clinical status stabilizes, she's transferred to an acute rehabilitation facility to continue therapy and improve her functional ability.

Vigilant care

Ruptured cerebral aneurysm can have devastating effects on the patient and her family. By providing vigilant nursing care, you help your patient combat serious complications and improve her chance of survival and restored independence.

SELECTED REFERENCES

Bader, M.: "The Complexity of Caring for Patients with Ruptured Cerebral Aneurysm: Case Studies," AACN Clinical Issues. 8(2):182-195, May 1997.

Campbell, P., and Edwards, S.: "Hyperdynamic Therapy: The Nurse's Role in the Treatment of Cerebral Vasospasm," Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 29(5):318-324, October 1997.

Hickey, J.: The Clinical Practice of Neurological and Neurosurgical Nursing, 4th edition. Philadelphia, Pa., Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1997.

Morrison, S.: "Guglielmi Detachable Coils: An Alternative Therapy for Surgically High-Risk Aneurysms," Journal of Neuroscience Nursing. 29(4):232237, August 1997.

SELECTED WEB SITES

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke http:/Iwww.ninds.nih.gov

National Stroke Association http://www.stroke.org

Last accessed on January 4, 2001.

BY DONNA MOWER-WADE, RN, CNRN, CS, MS Trauma Advanced Practice Nurse

MARY C. CAVANAUGH, RN, CCRN, MSN Neurosurgical Clinical Nurse Specialist

DOLORES BUSH, MSPT Physical Therapist

Christiana Care Health Services Newark, Del.

Copyright Springhouse Corporation Feb 2001

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved