To the Editor:

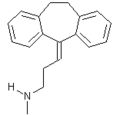

We would like to congratulate da Costa et al (August 2002) (1) on extending the database on nortriptyline for tobacco dependence.

However, we would like to comment on several issues regarding their study. First, we would caution against comparing results across studies. Comparing efficacy for given treatments is best done using direct comparative data. In the absence of such data, results from similarly designed studies may be compared as long as limitations of the comparison are noted.

In the present study, abstinence rates appear to be based on patient self-report without biological confirmation, which is the standard for determining efficacy in smoking cessation studies. Additionally, efficacy is reported as the 1-week quit rate at the end of treatment. No data on quit rates at other time points during treatment or on continuous quit rates are presented. The limited quit data reported and the lack of biological confirmation of quitting do not allow for an informed comparison with bupropion studies. In addition, this study employed relatively intensive group therapy administered by psychiatrists. Such therapy would be expected to elevate quit rates as opposed to quit rates in studies that used a less intensive behavioral intervention.

Regarding a separate issue, and in contrast to a statement by the authors, the cardiovascular profile for bupropion is well-established. Bupropion therapy has been evaluated in multiple depression and smoking cessation studies, and has been shown to be associated with minimal cardiovascular risk. (2,3) In a study of bupropion therapy in smokers with cardiovascular illnesses, (4) the safety profile was similar to that seen with bupropion therapy in a general smoking population. In the present study of nortriptyline therapy, 16% of smokers accepted into the study were excluded due to ECG alterations, which further raises questions about comparability.

In conclusion, it is inappropriate to conclude that success rates obtained with nortriptyline therapy in this study are comparable to those established with bupropion. In fact, when available evidence of efficacy and safety were reviewed by Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, only bupropion and nicotine replacement therapy were recommended as first-line treatments. (5)

REFERENCES

(1) da Costa CL, Younes RN, Lourenco MT. A prospective randomized double blind study comparing nortriptyline to placebo. Chest 2002; 122:403-408

(2) Wenger TL, Stern WC. The cardiovascular profile of bupropion. J Clin Psychiatry 1983; 44:176-182

(3) Roose SP, Dalack GW, Glassman AH, et al. Cardiovascular effects of bupropion in depressed patients with heart disease. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:512-516

(4) Tonstad S, Murphy M, Astbury C, et al. Zyban is an effective and well tolerated aid to smoking cessation in smokers with cardiovascular disease: 12 months follow-up phase data. Paper presented at: European Society of Cardiology Congress, Berlin, Germany, September 2002

(5) Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; June 2000

Carlos Jimenez-Ruiz, MD, PhD

Jose I. De Granda Orive, MD

Public Health Institute

Madrid, Spain

Correspondence to; Carlos Jimenez-Ruiz, MD, PhD, Smokers Clinic, Public Health Institute, Madrid C/Iriarte, 16 Bis, 28028 Madrid, Spain; e-mail: victorina@ctv.es

To the Editor:

We would like to thank Drs. Jimenez-Ruiz and Orive for their interesting letter and detailed comments. We agree that direct comparison between the results of different studies should be done cautiously. Our comments in the discussion suggest that the results obtained in our trial are similar to those achieved with bupropion administration in other published series. As to abstinence rates in our study, they were reported as 1 week after treatment, as well as 3-mouth and 6-month success rates following treatment.

In a meta-analysis (1) of published studies comparing self-reported smoking status with results of biochemical validation, the authors observed high level of sensitivity and specificity for self-reported abstinence. The authors observed that despite their believed objectivity, biochemical measures could not be considered the "gold standard," nor were they perfect measurement of accuracy. Carbon monoxide and thiocyanate can be elevated even in individuals who do not use tobacco. Biochemical tests also have limited ability to detect very low levels of smoking that would be expected from recent quitters. Only cotinine-plasma may be the biochemical test of choice if adequate resources were available for collection and analyses; however, our study compared success rates of abstinence in placebo and nortriptyline groups, in order to control confusion factors, and showed that nortriptyline significantly increases the smoking cessation rate.

There is no objective reason to expect differences in abstinence rates due to the type of behavioral group therapy. It is rather difficult to compare behavioral approaches as more or less intensive.

About the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research review and guidelines, (2) published in June 2000 and including data from studies found in the medical literature before that particular date, the authors considered nortriptyline as the drug of choice for second-line treatment of tobacco addiction. That decision was not based on its lack of effectiveness. As thee authors stated, nortriptyline was "identified as efficacious and may be considered by clinicians." (2) We think that data from our study, as well as others recently published could add to the evidence of the efficacy of nortriptyline in the present context.

Drs. Jimenez Ruiz and Orive stated that "in contrast to a statement by the authors, the cardiovascular profile for bupropion is well established." We included in our discussion the following citation: "there have been no clinical trials establishing the safety of bupropion in patients with cardiovascular disease," quoted from the same reference cited in their letter. (3) In this study with 36 depressed patients, 5 patients could not complete treatment because of the adverse effects of bupropion. The authors concluded that studies with more subjects are needed to confirm that the cardiovascular profile of bupropion may make this drug a useful agent in patients with preexisting cardiovascular disease. The other, more recent reference cited by Drs. Jimenez-Ruiz and Orive was presented in a medical meeting in September 2002, after our article was published. We agree with their statement that bupropion cardiovascular adverse effects are not considered a major restriction to its use, as further discussed in our article. (4)

REFERENCES

(1) Patrick DL, Cheadle A, Thompson DC, et al. The validity of self-reported smoking: a review and meta analysis. Am J Public Health 1994; 84:1086-1093

(2) Fiore MC, Bailey WC, Cohen SJ, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 2000

(3) Roose SP, Dalack GW, Glassman AH, et al. Cardiovascular effects of bupropion in depressed patients with heart disease. Am J Psychiatry 1991; 148:512-516

(4) Costa CL, Younes RN, Lourenco MT. A prospective, randomized, double-blind study comparing nortriptyline to placebo. Chest 2002; 122:403-408

Celia Lidia da Costa, MD

Riad Naim Younes, MD, PhD

Maria Teresa Lourenco, MD, PhD

Hospital Cancer-AC Camargo

San Paulo, Brazil

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physician (e-mail: persmissions@chestnet.org).

Correspondence to: Celia Lidia da Costa, MD, Depart de Torax, Hospital Cancer-AC Camargo, Rua Prof A. Prudente No 211 San Paulo 01509-010, Brazil

COPYRIGHT 2003 American College of Chest Physicians

COPYRIGHT 2003 Gale Group