Find out how to recognize the clues of this all-too-common disorder and get your patient the help he needs.

CLARK JONES, 45, lost his job last year and can't find work. Recently, his wife left him, taking the children. He arrives at the emergency department one morning complaining of chest pain and anxiety. All his diagnostic lab studies, including serial electrocardiograms and serum cardiac markers, are within normal limits. Mr. Jones is later diagnosed with major depression.

In any given year, more than 2 million American adults suffer from a depressive illness. People at risk for depression include those who've lost loved ones or a job, those with a personal or family history of depression, and those who have a serious medical or psychiatric condition. Older adults are also at high risk. The incidence of depression is about twice as high in women than in men, possibly because of hormonal differences between the sexes. Many women are especially vulnerable to depression after childbirth. (See Shades of the Baby Blues.)

Untreated, depression can be as debilitating to a person's quality of life and daily functioning as any chronic disease. And up to 15% of people with major depression or in the depressive episode of bipolar disease commit suicide.

Between 40% and 60% of Americans with depressive illness receive their only health care from health care professionals who don't specialize in mental illness. So even if psychiatric nursing isn't your specialty, you may be the first to recognize a patient in trouble and help him get treatment. In this article, I'll provide information and guidelines you can follow.

Out of balance

Although still not well understood, depression is thought to involve an imbalance of central nervous system neurotransmitters. Medications used to treat depression affect the availability of neurotransmitters at the neuronal synapse. For details, see How Selected Medications Ease Depression and Bipolar Disorder

Signs and symptoms of major depression vary from person to person and among men and women. For example, a man may be angry rather than sad, and he may be less willing to admit to feeling depressed than a woman.

Typically, however, the patient experiences a persistently sad or depressed mood (children and adolescents may be irritable), a loss of interest in things that were once pleasurable (anhedonia), and at least three of the following psychological or physical signs and symptoms, which differ from his normal responses, during the same 2-week period:

* reduced energy or fatigue, lack of motivation or drive

* disturbances in appetite and weight

* inattention to grooming, poor hygiene

* alterations in sleep patterns (insomnia, early-morning awakening, or oversleeping)

* lack of concentration

* forgetfulness

* feelings of worthlessness, hopelessness, helplessness, guilt, indecisiveness, or low self-esteem

* psychomotor retardation or agitation

* thoughts of death or suicide.

Start your assessment by taking the patient's vital signs, doing a health history, and performing a comprehensive physical exam. Ask about a personal or family history of depression or other mental illness, suicide, or substance abuse. Keep in mind that many depressed patients, especially men, use drugs or alcohol to mask depression or ease symptoms. Also assess for concurrent conditions that often accompany depression. (See Depression's Fellow Travelers.)

No studies can diagnose depression, but lab tests and imaging studies can help rule out other disorders associated with depression, such as hypothyroidism or brain tumors.

A mental status examination can help diagnose or rule out other psychiatric disorders and substance-abuse problems by assessing areas such as the patients mood, affect, thought processes, memory, judgment, presence or absence of hallucinations and delusions, and risk of harming himself or others. Additional assessment tools include several well-established rating scales, including the Beck Depression Inventory, Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, and Geriatric Depression Scale, that may be used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms and response to treatment.

If you suspect your patient has depression, evaluate him for suicide risk factors, which include previous suicide attempts, family history of suicide, isolation and a lack of support systems, a sense of helplessness and hopelessness, and substance abuse. Assess his state of mind with direct questions such as these:

* Lately, have you felt as if life isn't worth living or you'd be better off dead?

* Have you ever thought of doing away with yourself?

* If so, do you have a plan?

* Have you tried to kill yourself in the past? If so, what was going on in your life then?

Don't worry about "putting ideas into his head." If he's thinking about suicide already, your questions may bring his intentions out into the open and encourage him to discuss his feelings and accept treatment. Immediately refer a patient who may be an imminent danger to himself or others to a mental health professional for a psychiatric evaluation.

Treatment: Combining therapies

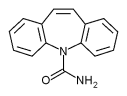

Research shows that the most effective treatment for major depressive illness combines psychotherapy and antidepressant drugs. Many new antidepressants have become available in recent years, including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as fluoxetine (Prozac) and citalopram (Celexa). A patient who doesn't respond well to one course of drug therapy now has an even wider array of options.

Medication and psychotherapy work hand in hand. Medication can improve concentration, increase the patient's motivation for psychotherapy, and reduce relapse; psychotherapy can improve his adherence to the medication regimen, teach him better ways to deal with stress and negative emotions or thoughts, and help him function better in daily life.

One type of psychotherapy that's effective for patients with depression and anxiety is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). This therapy helps patients understand how their thoughts become distorted and contribute to depression and anxiety. Patients learn coping behaviors that reduce feelings of helplessness, anxiety, and distress generated by distorted thinking processes. Involving supportive family members in therapy may also help.

Dysthymic disorder: Less disabling but persistent

Less severe and disabling than major depression, dysthymic disorder is a persistently depressed mood that the patient experiences on most days for at least 2 years. Although considered distinct from major depression, dysthymic disorder can precede or occur concurrently with major depression.

A patient with dysthymic disorder has two or more of these symptoms: increased or decreased appetite, increased or decreased sleep, fatigue or low energy, poor self-image, decreased concentration or indecisiveness, and feelings of hopelessness. During a 2-year period, these symptoms aren't absent for more than 2 consecutive months.

Patients with this chronic disorder also may have alternating episodes of major depression (sometimes called double depression). Treatment for dysthymic disorder is similar to that for major depressive disorder.

Seasonal sadness

A patient who's sad during the winter months and happy during spring and summer may be suffering from seasonal affective disorder, which affects more women than men. Typical symptoms are a low mood and other depressive symptoms, such as increased sleep, weight gain, and fatigue. Thoroughly evaluate the patient to rule out medical or psychiatric conditions. Treatment consists of bright-light therapy, antidepressants, or cognitive behavioral therapy.

Bipolar disorder: Ups and downs

Formerly called manic depression, bipolar disorder consists of cycles in the patient's mood, energy level, concentration, judgment, and ability to function. Between the highs of mania and the lows of depression, the patient's mood is normal. Typically, symptoms of bipolar disorder emerge during adolescence or early adulthood.

During a depressive episode, the patient will have symptoms consistent with major depression. During a manic episode, he'll have three or more of the following symptoms most of the day, nearly every day for at least 1 week:

* increased energy or goal-directed activity

* an excessively elevated, euphoric mood

* intense irritability

* racing thoughts

* excessive, rapid speech, including jumping from one topic to another

* less need for sleep

* poor judgment

* clear evidence of distractibility

* seductive, provocative, or aggressive behaviors

* hypersexuality

* delusions of grandeur.

Some people experience mixed episodes, when they feel depressed and energized simultaneously. Signs and symptoms include agitation, sleep disturbances, altered appetite, self-destructive behaviors, and psychosis (hallucinations and delusions).

Hypomania is a distinct period in which the person's chief mood is elevated, expansive, or irritable. Normally, these symptoms alternate with symptoms of major depression and aren't severe enough to impair function or require hospitalization. Delusions are less likely to occur with hypomania.

Bipolar disorder, like other mood disorders, is recurrent and chronic, but when symptoms are managed, the patient is at less risk for suicide and can live a more normal life. Again, drugs and psychotherapy are the mainstays of treatment. Because the disorder is chronic, treatment should be continuous rather than episodic.

Lithium and anticonvulsants such as valproic acid (Depakene), carbamazepine (Tegretol), lamotrigine (Lamictal), and topiramate (Topamax) have been successful as monotherapy and adjunct therapy with antidepressants for treating bipolar disorder and reducing relapse. However, these drugs don't exert therapeutic effects for 10 to 14 days, so additional drugs, such as the atypical antipsychotics olanzapine (Zyprexa) and risperidone (Risperdal), and anxiolytic drugs may also be indicated to stabilize symptoms of acute mania during early treatment. Long-acting or short-acting anxiolytic drugs such as clonazepam (Klonopin) or lorazepam (Ativan) may be combined with atypical antipsychotics to help the patient sleep and to reduce anxiety and agitation.

Mood-stabilizing drugs are contraindicated in pregnant women because of the risk of harm to the fetus. In women of childbearing age or who are breast-feeding, the benefits of therapy must be weighed against the risks because these drugs are potentially harmful to a nursing infant.

During therapy, closely monitor the patient's serum drug level. Document his response to treatment and any adverse drug reactions. Teach him (and his family, if he gives permission) about his bipolar disorder and prescribed medications, dietary precautions, and other treatments.

Psychotherapeutic interventions for bipolar disorder include CBT, psychoeducation (which includes teaching the patient how to recognize signs of relapse), coping and social skills, family therapy and interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (to help the patient maintain regular routines and reduce the risk of provoking or worsening affective symptoms).

Shocking treatment

Electroconvulsive therapy may be used in an emergency to relieve severe symptoms of major depression or bipolar disorder, such as psychosis or suicidal ideation. This therapy may also be used in patients who haven't responded well to drug therapy, those for whom drugs pose too great a risk (such as patients with certain medical conditions that preclude the use of medications), and those who are hypersensitive to medications. For more information, see "Electroconvulsive Therapy Sheds Its Shocking Image," in the March issue of Nursing2003.

Happier endings

Because depressive disorders are complex, understanding their biological and psychosocial underpinnings can help you identify patients early, before they become a danger to themselves or others. Helping the patient receive integrated drug therapy and psychotherapy can restore normal brain chemistry, reduce psychosocial distress, and let the patient start enjoying life again.

SELECTED WEB SITES

National Institute of Mental Health: Bipolar Disorder

http://www.nimh.nih.gov/ healthinformation/bipolarmenu.cfm

National Institute of Mental Health: Depression

http://www.nimh.nih.gov/ healthinformation/depressionmenu.cfm

National Institute of Mental Health: Men and Depression

http://menanddepression.nimh.nih.gov/ infopage.asp?id=10

Last accessed on November 1, 2004.

To take this test online, visit http://www.nursingcenter.com/ce/nursing.

CE Test

Is your patient depressed?

Instructions:

* Read the article beginning on page 54.

* Take the test, recording your answers in the test answers section (section B) of the CE enrollment form. Each question has only one correct answer.

* Complete registration information (Section A) and course evaluation (Section C).

* Mail completed test with registration fee to: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, CE Croup, 333 7th Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, NY 10001.

* Within 3 to 4 weeks after your CE enrollment form is received, you will be notified of your test results.

* If you pass, you will receive a certificate of earned contact hours and an answer key. If you fail, you have the option of taking the test again at no additional cost.

* A passing score for this test is 11 correct answers.

* Need CE STAT? Visit http://www.nursingcenter.com for immediate results, other CE activities, and your personalized CE planner tool.

* No Internet access? Call 1-800-933-6525, ext. 6617 or ext. 6621, for other rush service options.

* Questions? Contact Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 646-674-6617 or 646-674-6621.

Registration Deadline: December 31, 2006

Provider Accreditation:

This Continuing Nursing Education (CNE) activity for 2.0 contact hours is provided by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, which is accredited as a provider of continuing education in nursing by the American Nurses Credentialing Center's Commission on Accreditation and by the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN 00012278, CERP Category A). This activity is also provider approved by the California Board of Registered Nursing, Provider Number CEP 11749 for 2.0 contact hours. LWW is also an approved provider of CNE in Alabama, Florida, and Iowa and holds the following provider numbers: AL #ABNP0114, FL #FBN2454, IA #75. All of its home study activities are classified for Texas nursing continuing education requirements as Type I. This activity has been assigned 1.0 pharmacology credit.

Your certificate is valid in all states. This means that your certificate of earned contact hours is valid no matter where you live.

Payment and Discounts:

* The registration fee for this test is $13.95.

* If you take two or more tests in any nursing journal published by LWW and send in your CE enrollment forms together, you may deduct $0.75 from the price of each test.

* We offer special discounts for as few as six tests and institutional bulk discounts for multiple tests. Call 1-800-933-6525, ext. 6617 or ext. 6621, for more information.

SELECTED REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, text revision. Washington, D.C., American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

Brown, E., et al.: "Recognition of Depression among Elderly Recipients of Home Care Services," Psychiatric Services. 54(2):208-213, February 2003.

Levi, V, et al.: "Psychopharmacologic Therapy," in Psychiatric Nursing. Biological and Behavioral Concepts, D. Antai-Otong (ed). Clifton Park, N.Y., Delmar Learning, 2003.

Sachs, G., et al.: "The Expert Consensus Guideline Series: Medication Treatment of Bipolar Disorder 2000," Postgraduate Medicine. Spec. No.: 1-104, April 2000.

Thase, M., and Sachs, G.: "Bipolar Depression: Pharmacotherapy and Related Therapeutic Strategies," Biological Psychiatry. 48(6):558-576, September 15, 2000.

Winston, A., and Winston, B.: Handbook of Integrated Short-Term Psychotherapy. Washington, D.C-, American Psychiatric Press, 2002.

BY DEBORAH ANTAI-OTONG, RN, NP, CNS, MS, FAAN

Deborah Antai-Otong is director/program specialist and mental health provider at the VA North Texas Healthcare System in Dallas.

The author has disclosed that she has no significant relationship with or financial interest in any commercial companies that pertain to this educational activity.

Copyright Springhouse Corporation Dec 2004

Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved